New Experiences and Discoveries: The Libraries and Archives of Tomorrow

Ng Cher Pong, Chief Executive Officer of the National Library Board, shares his thoughts and insights on how libraries and archives can stay relevant in today’s world.

By Kimberley Chiu

The three pillars of the National Library Board are the National Library, the National Archives and the public libraries. How will the libraries and archives of the future look like to you?

Libraries and archives are repositories of knowledge, information and cultural heritage. Their objectives are to collect and preserve materials, and make these accessible to library patrons for their educational, recreational and informational needs. At the National Library Board (NLB), in addition to the provision of traditional library and archives services, it’s increasingly going to be about experiences – the experience of discovery, and the idea of library and archives as enablers of discovery. This is important because when we reflect on how we want patrons to experience our services, we have to think beyond the traditional roles of libraries and archives. We have to innovate, experiment and keep people interested, inspired, engaged and curious to know more. These are things that institutions like libraries and archives should do.

What do you think are the key features of the libraries and archives of the future?

The starting point for thinking about the libraries and archives of the future is the idea that we need to go beyond transactions. Our spaces will increasingly be about experiences. This brings us to the question: why would someone choose to visit a library?

Compare this with the retail industry: you can buy most things through e-commerce and have them delivered to your home. Why would anyone go to a retail store? Libraries are not dissimilar; after all, you can now get library books delivered to your home or to reservation lockers. You can even access eBooks from your phone. Therefore, the library needs to offer you something more than books.

In 2024, the total visitorship at the National Library, public libraries, National Archives and the Former Ford Factory was 19.8 million. This is a healthy number but it is not something to take for granted. To maintain and grow this number, we have to figure out how our spaces can create experiences that add value to our patrons.

Our patrons’ needs are at the heart of what we do, and they come to us for many different reasons. Some want individual seats and quiet corners where they can have a respite; others come for books and programmes. These core services continue to be important to us. But we have to also provide interesting content-based experiences that present our patrons with something unexpected, such that they will want to keep coming back regularly.

I recently visited the Beijing Capital Library, which won the Public Library of the Year Award by the International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions (IFLA) in October 2024. That library invested heavily in experiences for patrons across the age spectrum. For example, the children’s section has a 4D cinema complete with moving seats and special effects to make storytelling come alive. Such an experience may not usually be associated with libraries, but it is an illustration of how we need to break out of our traditional thinking and consider what makes sense from the user’s point of view.

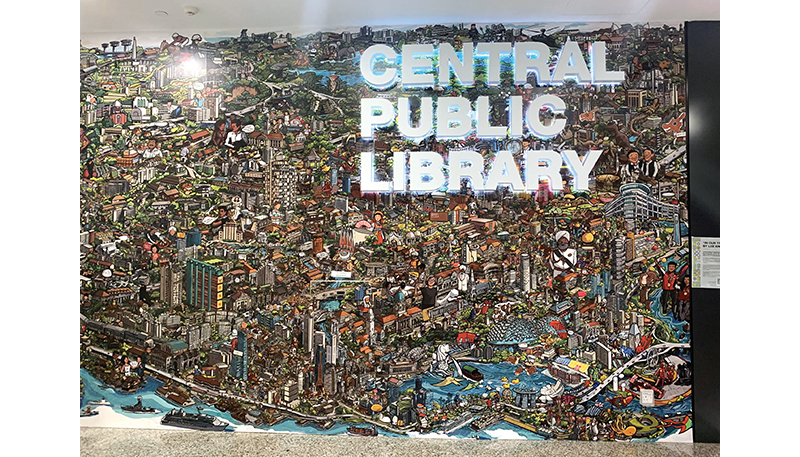

Many of these experiences will also be omni-channel – an experience that blurs the line between physical and digital – which allows you to access digital content in a physical space. We’ve already done this with new technology like the AR (augmented reality) artwork at the Central Public Library showcasing Singapore’s landmarks, but there is scope to do much more.

My last point about the libraries and archives of the future is that we must be driven by discovery. This has always been the underlying reason people come to the library: to discover new and unexpected things. If you already have a clear idea of what you want, such as a specific title, there are many options to fulfil this need. This includes ordering from Amazon.

But we do know that many people visit libraries – and bookshops – because they like browsing the shelves, hoping to make a serendipitous discovery. There is enormous appeal in the act of browsing, and thus we need to better develop browsing as a service to enhance one of the key appeals of physical spaces.

Browsing suggests a greater role for serendipity in the library. Do you think that NLB’s interest in building suggestion algorithms and personalised recommendations interferes with our ability to provide a robust browsing service?

That depends on how you structure your algorithm. Commercial operators may choose to keep pushing the same types of resources and products to a user because doing so makes the user more likely to buy something. By doing so, you are indeed restricting a user’s browsing behaviour. But for NLB, we are not constrained by such commercial considerations. We have freer rein to be more creative with the content we recommend, and to offer a broader range of reading materials to our patrons, including from our archives. We can take more risks and offer greater variety because we’re not under pressure to monetise what people choose, and because we genuinely believe in providing breadth.

We do have to think carefully about how we can provide browsing as a service in the digital space. People are so used to social media feeds. Can a digital library look like a social media feed? Can a digital library’s interface appear almost infinite in the same? How and what can we learn from social media algorithms – what lessons can we take from them?

Do you think it’s possible for NLB to compete with social media for attention? Do we have the capabilities to match the experience of, for instance, TikTok?

We aren’t directly competing with social media. We may learn from and emulate their interfaces but the content we offer is different: we are reputable, substantial and of guaranteed quality. In fact, NLB is uniquely placed to offer this content because we’re a combined institution: we not only have the public libraries but also the National Library and the National Archives.

We have the capabilities and resources of three different institutions under one roof. This offers us unique opportunities to deliver rich content and experiences to our patrons. An example is how we have tapped on generative artificial intelligence (Gen AI) to enable our patrons to learn more about S. Rajaratnam through our ChatBook service.1 This project could never have happened without the foundation laid by years of conscientious archival work: the accumulation of materials, the meticulous documentation of events, the collection of oral history interviews. This project shows the edge that NLB has over social media when it comes to delivering credible and quality services.

More importantly, we are not competing with social media to achieve the same aims. Social media sites are competing with one another to monetise attention. Primarily, they want more eyeballs on their apps. Our primary purpose is different: we want people to discover more and to that end, we want to apply the lessons we learn from social media to make learning more appealing and accessible to all our patrons. If people prefer short-form content such as TikTok videos, we can offer such content, but use them to invite viewers to go deeper; to expand both their breadth and depth of a particular topic.

How can we make this deeper discovery more appealing to our patrons? As you said, people are increasingly accustomed to the surface-level consumption of content that social media provides. So how can we make deep learning a bigger part of the lives of Singaporeans?

I believe that we need to meet our patrons where they are if we want to make our collections, programmes, services and the resources we offer a seamless part of their lives. There is, at present, a very clear line between “library spaces” and “non-library spaces”, but the libraries of the future ought to blur that line. One way that NLB has tried to do this is with Nodes, which bring library services into spaces that are not traditionally “library spaces”, like offices, cafés and even public transport.2 Beyond that, I think we can also blur these lines within our libraries.

This could involve co-locating with other services or businesses. A natural partner would be cafés, since there is already a strong association between books and coffee. Many of our libraries already have cafés, but there is a clear delineation between the café space and the library space: we can’t bring food and drinks from the café into the library, forcing an arbitrary interruption of what could have been a seamless experience of reading over a cup of coffee.

One day we should have a library where the café is not sequestered in one corner but instead occupies a central space in the library, with the ability to serve food and drinks throughout the library space.

The House of Wisdom Library in Sharjah in the United Arab Emirates has a similar concept,3 where you can even order a coffee at your seat using a QR code.

Another natural partner for us would be bookshops. In Chengdu, I came across a library that was co-located with a bookshop. In fact, it was inside the bookshop. The bookshop has newer titles, but only stocks titles that were likely to sell well. On the other hand, the library, since it is a non-commercial entity, carries a far wider selection of titles, including those with a niche audience. The library and bookshop complement one another, and together provide a better overall service to their visitors.

There are many good ideas from different libraries around the world and NLB is constantly learning and considering what might work in our local context. Specifically in relation to bookshops, I believe that libraries and bookshops are allies in building Singapore’s reading and learning ecosystem. Together with writers and publishers, we should join forces to enable the entire ecosystem to thrive. Only then can we make Singapore a reading nation, which is one of our biggest goals as an institution.

Most importantly, we have to keep in mind that public libraries serve a broad swathe of society, and we therefore need to have programmes and services for everyone. We have to be mindful that what works for one group of patrons might not work for another, and we must be attentive to the needs of our different customer segments. This is particularly so when creating experiences. Not every experience will appeal to every user. Nor should they be designed to do so. Instead, we will have to manage this to ensure that within the services we provide, there is something for every patron. This is an important consideration, particularly when making decisions on where best to invest our limited resources.

Do you feel that there are segments of society that we could work harder to include, or who might not yet see a place for themselves in the library?

At the moment, the library is seen primarily as a space for the young, so we are working hard to offer services to appeal to working adults as well as seniors. It’s especially important to serve our seniors well because Singapore’s population is ageing rapidly and we will soon become a super-aged society.

The profile of our seniors is also changing rapidly. Singapore went through a huge and rapid shift in our education system after independence, so the needs of the new generation of seniors are very different from their predecessors. The seniors of today are increasingly looking for new experiences: they travel, seek out educational opportunities and want exciting places where they can spend time without being forced to spend money. We have a lot to offer people at this stage of their lives, such as programmes where they can discover digital technology, workshops that help them develop new skills, and learning communities that will allow them to explore new interests and connect with other seniors.

We are also committed to making our spaces accessible to persons with disabilities. While Singapore has become increasingly inclusive, there are still too few public spaces designed for persons with disabilities – that not only accommodate them but make it possible for them to participate in the same way as any other user, and are built with their needs and desires in mind.

We tried to do so when we built Punggol Regional Library and learnt much from serving persons with disabilities. We now need to extend this approach to all our libraries going forward.4 It is important that anyone who wants to use the library can do so. It’s not just a numbers game for us: every patron matters, every segment of the population matters, and that includes persons with disabilities.

Society can feel increasingly atomised and isolating with the changes brought about by technology and other social forces. What can NLB do to combat this?

Community building is an important part of the work of the library, both now and in the future. It’s important for us to not only provide spaces for people to meet, but also be launchpads for new communities and social groups to form, learn and grow together. I especially love the idea of the community takeover, where people with good ideas can come and use our space to reimagine learning, facilitate community conversations and help build the library that they want to see.

Under LAB25 (“Libraries and Archives Blueprint 2025”), we have tested this idea with corporate partnerships. One example is the collaboration with local furniture stores where they deployed their furniture in our libraries, making our libraries feel more homely. In turn, they benefited from having a wider exposure of their furniture to the public. Such partnerships have the potential to shift the public perception of libraries – our patrons saw us as more welcoming and as a space with possibilities beyond what they’d expect of a traditional library. It helped them see the library as a place where you can do unexpected things.

What can we do when many of the things that keep people from the library – for instance, long working hours, or a lack of leisure time – are obstacles that are beyond our control?

We focus on addressing what is within our control. For instance, working adults may not have as much time to come and enjoy our spaces. We can’t do anything about their working hours, but we can make it easier for them to use our resources by offering delivery and reservation services, or by expanding our collection of eResources. We can make our libraries enticing to visit in their limited free time so that they choose to come to us when they do have time to spare.

With all the changes that libraries and archives will face, what do you think is the core value that they will continue to carry into the future?

I believe that reading, learning and discovery must continue to be our mainstay. Libraries and archives are, and always will be, institutions of reading and learning. No other institution can replicate our roles. But content consumption patterns have changed and will continue to do so. This is why libraries and archives need to transform. We need to stay relevant and be present in the lives of Singaporeans.

What role can the National Library and the National Archives play in the future, given an environment of information overabundance online and the widespread use of large language models such as ChatGPT?

Our National Library and National Archives are the collectors, preservers and repositories of Singapore’s history. The work that these institutions do in connecting Singaporeans to our past will only become more essential in the future.

Through the tireless work of our librarians and archivists, we have built rich collections that trace our nation’s history and culture – and not just in terms of traditional artefacts like documents, photographs and rare books, but also in terms of more innovative and engaging materials like audiovisual recordings, oral histories and social media posts.

These collections are essential resources for the new library experiences we aim to create. The explosion of information online – often muddled with unverifiable and untrue content – has overwhelmed many people and, as a result, has made them hungry for substance and authenticity. While Gen AI services like ChatGPT can help summarise information about an event in Singapore’s past, it cannot provide the same experience as encountering a rare photograph of that event, or hearing the real voice of someone who witnessed it, telling their story in their own words.

People today want stories that they know are true, that are documented in enough detail to bring them to life, and that are connected to their personal identities and everyday realities. The resources that the National Library and National Archives have so carefully collected and preserved can offer our patrons all these things and, when brought to life in exciting and interactive ways, provide patrons with not only a fun experience but also a deep and meaningful connection to their nation and its history.

This is part of the natural synergy between the National Archives and National Library, on the one hand, and the Public Libraries, on the other. Public libraries have an extensive community reach and are an integral part of the everyday life of many Singaporeans. Ongoing projects like the National Library’s Singapore Memories – Documenting Our Stories Together and the National Archives’ Citizen Archivist Project engage participants in the work of documenting our nation’s history, including contemporary events like the COVID-19 pandemic. Programmes like these blur the lines between library and non-library spaces, as well as the lines between archival work and the everyday work of creating our own personal and shared memories. More importantly, these programmes can help patrons find their place in the Singapore story, and demonstrate to them that their voices and contributions are valued by both NLB and the nation.

Kimberley Chiu is a Librarian with the Collection Planning and Development division. She selects books and eResources for children and young people across the public libraries.

Kimberley Chiu is a Librarian with the Collection Planning and Development division. She selects books and eResources for children and young people across the public libraries. Notes

-

In 2024, NLB launched the prototype of a generative AI-powered chatbook featuring founding father S. Rajaratnam. It enabled users to learn about his life and contributions to Singapore from content obtained from his authorised biography as well as collections from the National Archives and National Library. ↩

-

Nodes are new curated entry points into the National Library Board’s wide array of services and collections. They are an extension of learning experiences beyond physical libraries, and aim to bring content and services to wherever people frequent such as shopping malls, community centres, MRT stations, parks and even McDonald’s outlets. ↩

-

The House of Wisdom, a library and cultural centre, was commissioned in celebration of Sharjah winning the 2019 UNESCO World Book Capital. It is envisioned as a social hub for learning, supported by innovation and technology. ↩

-

Punggol Regional Library is equipped with the latest technology and equipment such as multimedia and borrowing stations, accessible keyboards and joysticks, and magnifiers with text-to-speech functions, enabling persons with physical and visual impairments to have easier access to eBooks, audiobooks, eNewspapers and eMagazines. There are also facilities like the Calm Pod and calming corners, which are equipped with sensory kits and toys. ↩