Daylight Robbery: Singapore’s Shifting Time Zones

In 1982, Singapore adjusted its time zone to follow Malaysia’s national synchronisation. But this was not the only instance that Singapore had undergone time zone changes.

By Kenneth Tay

In 1985, 40 years after the end of the Japanese Occupation, a reader wrote to the Singapore Monitor seeking advice on his or her time of birth.1 Born during the Occupation years, the reader’s birth time was registered as 5.30 pm on the birth certificate. The person wanted to know if this was Singapore time or Japan’s Central Standard Time (commonly referred to as “Tokyo Time”).

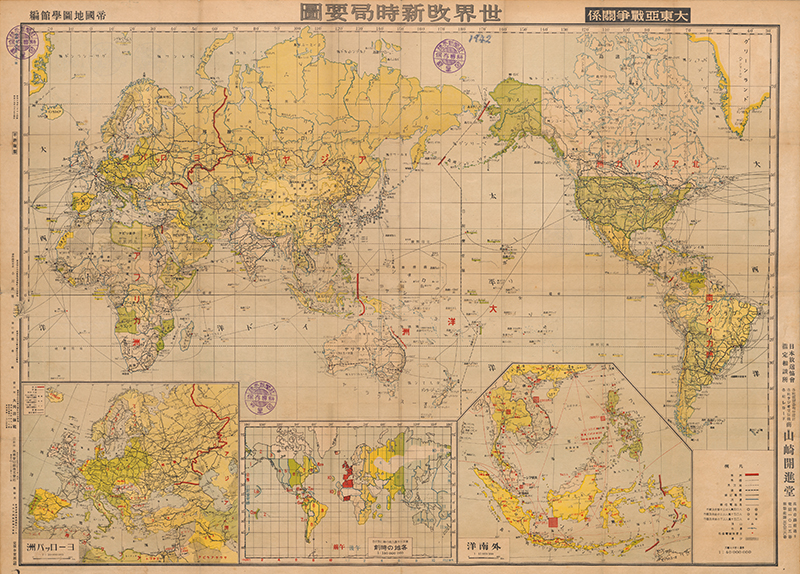

When Singapore came under Japanese control in February 1942, one of the first things the Japanese did was to announce that Singapore and British Malaya would fall under the same time zone as Tokyo, which was one-and-a-half hours ahead of Malayan time.2 The occupation of Singapore was more than spatial; it became temporal as well, colonising Singapore through time. Public clocks in Singapore were adjusted from the local time zone of seven-and-a-half hours ahead of Greenwich Mean Time (GMT+07:30) to nine hours ahead (GMT+09:00).3 The residents of Singapore had to adjust their body clocks to the rhythms of Japanese imperial time.

However, this change was not as simple or straightforward as it seemed. In February 1944, two years into the time adjustment, the Syonan Shimbun reported that people in Singapore were still making appointments based on the local time observed earlier rather than Tokyo Time: “There seems to be still not a few people who have not awakened to the hour, so to speak. These people are still making appointments by ‘local’ time, with the result that there has been much confusion and often disappointment which may even be more unfortunate, if not disastrous.”

This was even after all public clocks in Singapore had been synchronised to Tokyo Time.4 (It would be fascinating to know if this non-observation of Tokyo Time was, in fact, a form of quiet resistance, a bodily non-compliance.)

But this confusing sense of living in double time is precisely why our 1985 reader had questions regarding the registered birth time of 5.30 pm which, according to the reply by the Singapore Monitor, was Tokyo Time. If the reader wished to have the time changed, he or she could obtain a birth extract at the National Registration Department, they advised.5

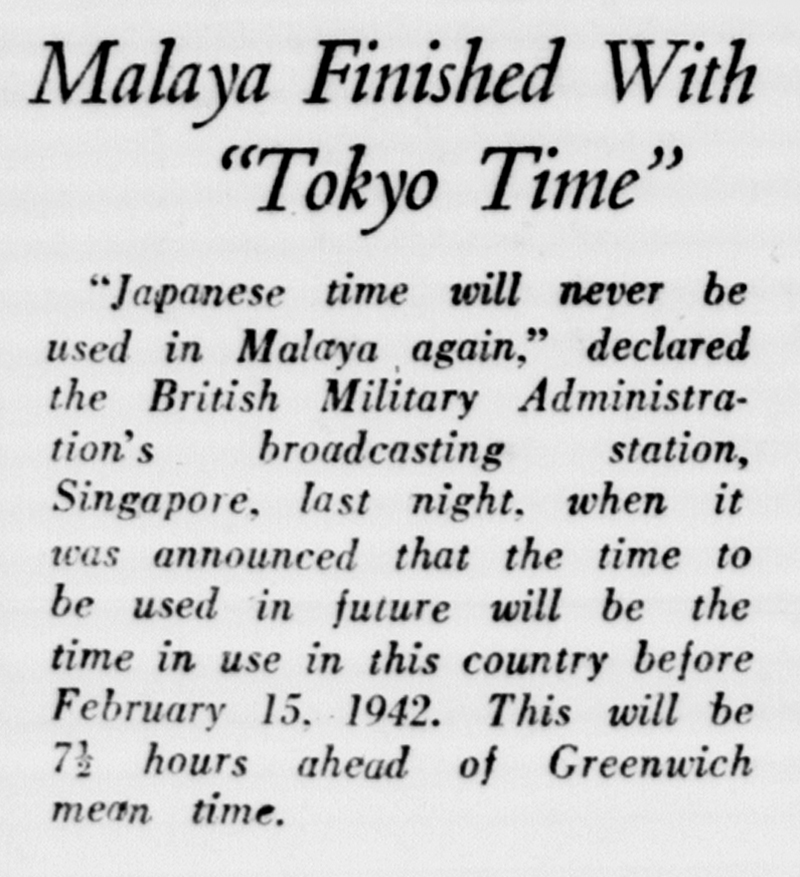

Once the Japanese Occupation ended, Singapore reverted to its previous time zone of seven-and-a-half hours ahead of GMT (GMT+07:30).6 This remained Singapore’s official public time until the Malaysian government announced in 1981 that it would be synchronising the time between West Malaysia (GMT+07:30) and East Malaysia (GMT+08:00), moving West Malaysia half an hour forward. Singapore’s government decided to follow suit and the change came into effect in Singapore on 1 January 1982.7

On New Year’s Eve, the Straits Times quipped that merrymakers out on the town “will find their happy times ending a little sooner than they are used to” and “all because 1982 will leap in half-an-hour sooner, with midnight chiming at the ‘old’ 11.30 pm on Dec 31”.8

Not a Minute Change

As the Japanese Occupation has shown, time zones can become a tool of political control, an extension of an empire’s territory in time. Malaysia, prior to its time zone adjustment in 1982, had been operating on two different national time zones: one for the western peninsula at GMT+07:30 for cities such as Kuala Lumpur and Penang, and another for East Malaysia at GMT+08:00 for cities such as Kota Kinabalu and Kuching. This split was due to the different longitudinal positions of Peninsular Malaysia and the eastern territories of Sabah, Sarawak and Labuan.

The Malaysian government synchronised both time zones to align business hours and improve coordination between the two territories. This was also done in hopes of fostering a stronger sense of an integrated Malaysia.9 In other words, the decision to change time zone in 1982 had both a political and economic dimension.

Meanwhile, Singapore’s decision to follow Malaysia’s time zone change came about largely due to the “many close ties between the peoples and governments of Singapore and Malaysia,” as noted in the press release issued by the Singapore Ministry of Culture. The sheer volume of trade and travel between the two countries, and the close commercial and financial links were also cited as factors in Singapore’s decision to align its time zone with that of Malaysia’s.

“The balance of advantage would be in Singapore’s favour if time was changed to Malaysian time,” said R.W. Lutton, the chairman of the Singapore International Chamber of Commerce and Industry. Y.M. Jumabhoy, the president of the Singapore Indian Chamber of Commerce felt that a half hour difference meant a lot of difference in business. “If Singapore does not change its time, it would mean half an hour of reduced contacts, especially since most business dealings are conducted over the telephone.” There were similar sentiments across the Causeway, with Malaysian businessmen saying that it “would be ‘pragmatic and logical’ for Singapore to keep in time with Malaysia”.10

Singapore’s decision to move its time ahead by 30 minutes proved even more fortuitous, both politically and economically, during the 1980s. Prior to the time zone adjustment, banks on the American west coast (at GMT-08:00) would be closing just when traders in Singapore were beginning their day (GMT+07:30).11 But with the additional half an hour at GMT+08:00, Singapore could function more effectively as a bridge between the closing hours of North American markets and the opening hours of the London and European markets. Moving to GMT+08:00 could also reap the additional benefits by being in the same time zone as Hong Kong and an emerging Chinese market.

Moreover, Singapore could also share an extra half hour of overlapping business hours with Japan’s then booming economy. This strengthened existing trade relations, as Japan had become the biggest foreign investor in Singapore’s economy by the end of the 1980s.12 The adjustment of 30 minutes forward was, therefore, not by any means a minute change. It helped secure Singapore’s position as a key financial hub for the global financing of the oil trade.13

Sleepless in Singapore

While there were obvious advantages in moving Singapore to GMT+08:00, were there unfortunate side effects? In a 2014 survey of sleep patterns, Singapore was reported to be the third most sleep-deprived city in the world, just behind Tokyo and Seoul. On average, Singaporeans were managing with just 6 hours and 32 minutes of sleep every night.14

In March 2015, a reader, concerned about sleeplessness in Singapore, felt compelled to write to the Today newspaper, arguing that the current time zone was to blame for it. “The sun rises at around 7 am, when most of the children are already headed for school or in school,” G. Kavidasan wrote. “Why do our schools not open at 9 am or 10 am so the children can have a good night’s sleep, wake up around 6 am or 7 am, do some studies or exercise, have a family breakfast and then go to school?” “[O]ur body clock syncs with the natural clock of the sun, and Singapore’s natural time zone should be seven hours ahead of Greenwich Mean Time (GMT+07:00).”15

Kavidasan’s argument was that Singaporeans should be waking up naturally when the sun rises at 7 am (GMT+08:00), or better still at 6 am (if the time zone is corrected to GMT+07:00 instead). Starting school or work at 9 am or 10 am would then allow people to have some hours of exposure to daylight, before getting on with the day’s work.

In fact, many of the concerns shared by Kavidasan were already brought up in public discussions during the 1930s, even before the Japanese Occupation.

Standardising Time in the Malay Peninsula

Prior to the 20th century, most towns or cities in Malaya kept localised time; noon was simply when the sun was observed at its highest point. This meant that local time was dependent on one’s longitudinal position on Earth. For every degree of longitude to the west, local noon would occur approximately four minutes later.16

In 1894, Singapore kept a local time that was computed at 6 hours, 55 minutes and 25.05 seconds ahead of time observed at the Royal Observatory Greenwich, London. This was based on Singapore’s longitudinal position of 103.854375° east of the Greenwich Meridian, with reference to the observatory located then at Fort Fullerton.17

This, however, meant that local clocks in two nearby towns could differ by a few minutes. For much of the 19th century, these differences did not affect the daily lives of many. Farmers, for example, relied on understanding the broad seasonal changes in their work, and did not require precise timekeeping. However, this changed with the birth of the steam engine and the subsequent establishment of railway systems. This was especially so for the British Empire, including its colonies in British Malaya. Train operators had to organise train schedules across towns that had hitherto been keeping their own individual local time. This meant that commuters very often had to navigate between confusing timetables.18

Commuters travelling between Penang and Taiping in the year 1900 would need to know that the local time kept by the two towns differed by approximately 18 minutes and factor that into their reading of train schedules between the two towns.19

At GMT+06:55:25, the local time of Singapore was “natural” insofar as it was based on Singapore’s longitudinal position on Earth. This meant that the time kept in Singapore was largely in sync with the sun’s rhythms as observed from Singapore.

This changed on 1 June 1905 when time throughout British Malaya became standardised to the mean time of the 105th meridian, at GMT+07:00. The minute differences between local times (e.g. Penang, Taiping, Singapore) were now evened out and synchronised to a uniform time zone.20 Trains, commuters and, ultimately, much of modern life in the Malay Peninsula now ran smoothly on a single time schedule.21

Daylight Robbery, c.1910–52

As soon as time became standardised in Malaya, there were suggestions made in 1910 to further adjust the time in Singapore. In a letter to the Straits Times, a concerned citizen noted that many early risers in Singapore were wasting away their daylight through the “aimless time spent before breakfast”. If business hours in Singapore (9 am to 5 pm back in 1910) could be adjusted to start at 8 am and end at 4 pm, or alternatively “putting the clock on an hour”, many in Singapore would benefit from having “an extra hour of daylight after office”.22 In short, the present business hours were robbing citizens of recreational time in daylight.

Such a letter should be understood in the context of British builder William Willett’s pamphlet, “The Waste of Daylight”, published just three years earlier. Willett’s chief concern was the varying hours of daylight experienced throughout the changing seasons in Great Britain. Willett had initially advocated to advance the clocks by 80 minutes in four 20-minute increments during April and reversing the process in September.23 However, by 1916, this plan was eventually changed to advance the clock by “one hour at 2 am on the third Sunday in April or about April 18th” and to reverse that motion at 2 am on “the third Sunday of September or about September 19th” in each year.24

While Singapore gets fairly consistent daylight throughout the year thanks to its latitudinal position, there were nonetheless worries that workers in Singapore were not getting enough daylight after the day’s work had ended.

As early as 1920, Governor of the Straits Settlements Laurence Guillemard had introduced a bill to adjust the clocks by “half-an-hour in advance of the mean time of the 105th meridian or seven-and-a-half hours in advance of Greenwich mean time”. Before moving to Singapore, Guillemard had experienced the benefits of daylight savings during the British summers.25

His suggestion was aimed at shortening the waking hours before work and giving workers more leisure time in the sun after work, thereby ensuring the good health of the working class without affecting existing business hours. However, this bill was ultimately withdrawn by the government due to opposition in the Legislative Council. One member, a John Mitchell, was even quoted as saying that if workers left their offices earlier in the day, “they might get sunstroke”.26

In 1932, when Guillemard had already left Malaya, his proposal was officially brought up by Arnold Robinson, a senior unofficial member of the Straits Settlements Legislative and Executive Councils.27 Despite some public opposition,28 the Daylight Saving Ordinance was eventually passed. With that, time in the British colonies of the Malay Peninsula and Singapore was advanced by 20 minutes on 1 January 1933 to become GMT+07:20.29

Many of the motivations behind daylight saving in 1930s Singapore were not so different from the social concerns shared much later in 2015. Unfortunately, several employers in Singapore took advantage of the “delayed” sunset to make their employees work longer hours. In 1934, just two years after the passing of the Daylight Saving Ordinance, unscrupulous employers were reported to have been robbing workers of their extra time in the sun.30

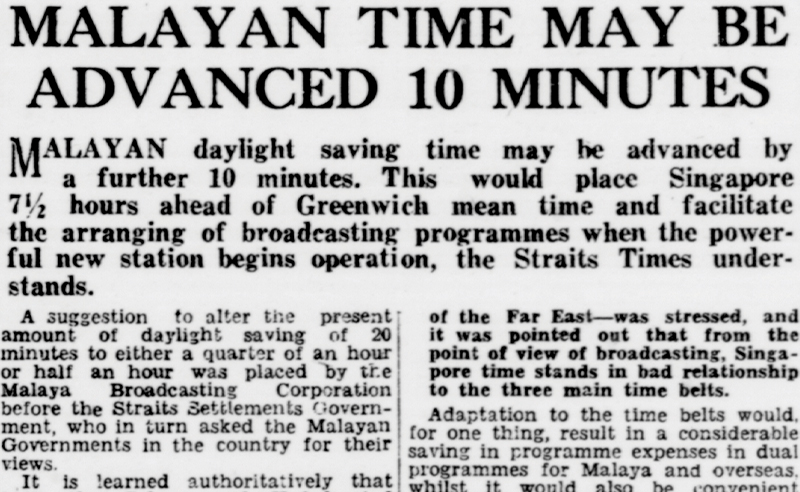

In September 1941, time in Singapore was again tweaked, advancing another 10 minutes under the Daylight Saving (Amendment) Ordinance. This time, it had less to do with the health of the working majority, and more to do with the programming time slots of the British Empire’s radio network. At GMT+07:20, Singapore’s time zone presented an inconvenience as the overseas programming of the British Broadcasting Corporation began on 15-minute intervals of the hour.31

During this period, the strategic importance of the radio network for the British Empire could not be underestimated. Adolf Hitler, the dictator of Nazi Germany had invaded Poland on 1 September 1939, and Britain and France declared war on Germany two days later. Bringing Singapore’s official time up to GMT+07:30 fitted nicely into the programming time slots of the British Broadcasting Corporation.32 As with the time zone changes enacted under the Japanese Occupation later on, this was yet another example of timekeeping being used as a political tool to control and influence a territory.

Here Comes the Sun (One Hour Later)

Since 1 January 1982, Singapore’s deviation from our natural solar time has become fixed at about one full hour away from the rhythms of the sun as observed locally from Singapore. While the adjusted time zone of GMT+08:00 represents a disconnect from the sun’s rhythms, it is also an example where the relationship to nature is perhaps made secondary in favour of Singapore’s economy and politics.

While there are those who might bemoan this present state of disconnect, there are others who argue that time is a man-made concept in the first place, or that the nature of time is fundamentally arbitrary.33 These are, perhaps, questions that can never be definitively answered. Nonetheless, the world continues to make do with the existing global system that was first centred on the Greenwich Meridian.34

Kenneth Tay is a Librarian with the Arts and General Reference team at the National Library Singapore. He is interested in the histories of global systems such as the internet, logistics and time zones, and where Singapore figures in them.

Kenneth Tay is a Librarian with the Arts and General Reference team at the National Library Singapore. He is interested in the histories of global systems such as the internet, logistics and time zones, and where Singapore figures in them. Notes

-

“Born During War Years,” Singapore Monitor, 12 April 1985, 13. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Tokyo Time All Over Malaya,” Shonan Times (Syonan Shimbun), 3 March 1942, 1. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

The Greenwich Meridian passes through the Royal Observatory Greenwich in London. For the longest time, throughout the 20th century, the Greenwich Meridian served as the Prime Meridian which is the internationally recognised zero-degree line of longitude dividing the Earth into its Eastern and Western hemispheres. ↩

-

“Only One Time – T.T. (Tokyo Time),” Shonan Times (Syonan Shimbun), 18 February 1944, 1. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Malaya Finished With ‘Tokyo Time’,” Straits Times, 7 September 1945, 1. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Singapore. Ministry of Culture, “Time Zone Adjustment,” press release, 20 December 1981. (From National Archives of Singapore, document no. 985-1981-12-20) ↩

-

“Tonight’s Revelry Will End Half-Hour Earlier,” Straits Times, 31 December 1981, 1. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Hamdan Aziz, et al., “The Change of Malaysian Standard Time: A Motion and Debate in the Malaysian Parliament,” International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Science 7, no. 12 (December 2017): 962–71, https://hrmars.com/index.php/IJARBSS/article/view/3725/The-Change-of-Malaysian-Standard-Time-A-Motion-and-Debate-in-the-Malaysian-Parliament; “Other Places, Times,” New Paper, 6 April 1993, 17. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Filomina D’Cruz, “S’pore ‘Should Follow’ New KL Time,” Straits Times, 11 December 1981, 14. (From NewspaperSG); Singapore. Ministry of Culture, “Time Zone Adjustment.” ↩

-

“Longer Hours for Forex Dealers,” Straits Times, 21 December 1981, 18. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Peter Hazelhurst, “5 PC Growth for Japan Forecast,” Straits Times, 14 July 1984, 44; “Robust Economy Helped Fuel Current Boom,” Straits Times, 21 September 1989, 26. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

George Joseph, “Union Urges Bank to Stay Open Longer,” Straits Times, 15 February 1978, 10; “Singapore’s Round-the-Clock Advantage,” Straits Times, 22 February 1989, 12. (From NewspaperSG); See also Woo Jun Jie, Singapore as an International Financial Centre: History, Policies and Politics (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2016), 28. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 332.095957 WOO); The story of Singapore’s economic development through the global oil trade is also a fascinating one. On this, see Hoong Ng Weng, Singapore, the Energy Economy: From the First Refinery to the End of Cheap Oil, 1960–2010 (London: Routledge, 2012). (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 338.27282095957 NG) ↩

-

Azimin Saini, “Refresh, Repeat,” Straits Times, 15 August 2015, 1. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

G. Kavidasan, “Singapore’s Time Zone Biggest Contributor to Sleeplessness Problem,” Today, 18 March 2015, 23. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Avraham Ariel and Nora Ariel Berger, Plotting the Globe: Stories of Meridians, Parallels and the International Date Line (Westport, Conn.: Praeger Publishers, 2006), 116. (From National Library Singapore, call no. R 526.6 ARI); David Prerau, Saving the Daylight: Why We Put Our Clocks Forward (London: Granta Books, 2005), 33. (From National Library Singapore, call no. R 389.17 PRE) ↩

-

“Time, Gentlemen, Please,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser (Weekly), 15 May 1894, 288. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Prerau, Saving the Daylight, 34–35. ↩

-

Viator, “Taiping Time and Other Topics,” Pinang Gazette and Straits Chronicle, 11 September 1900, 3. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“A Matter of Time,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 31 May 1905, 5. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Elsewhere, the territories of British North Borneo (present-day Brunei, Sabah, Sarawak and Labuan) also switched over to their “zone time” of GMT+08:00. See “The Year 1904,” Straits Budget, 5 January 1905, 1. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Tempus,” “Daylight Saving,” Straits Times, 26 July 1910, 8. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

William Willett, “The Waste of Daylight,” WebExhibits, accessed 29 June 2025, https://www.webexhibits.org/daylightsaving/willett.html. ↩

-

”Daylight Saving,” Malaya Tribune, 11 May 1916, 10. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“More Light,” Straits Budget, 14 July 1932, 3. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Daylight Saving,” Straits Times, 3 July 1920, 9; “Daylight Saving,” Straits Times, 13 June 1932, 10; “Legislative Council,” Straits Times, 6 September 1920, 9. (From NewsaperSG) ↩

-

“Twenty Minutes,” Malaya Tribune, 4 January 1937, 10; “Sir Arnold Robinson Dies in UK,” Straits Times, 3 March 1960, 14. (NewspaperSG) ↩

-

See for example, Pro Veritate Semper, “One Great Big Lie!” Straits Times, 8 November 1932, 19. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Clocks On,” Singapore Daily News, 17 December 1932, 4; “Here to Stay?” Pinang Gazette and Straits Chronicle, 16 March 1933, 8; “Summer Time,” Straits Times, 31 December 1932, 11. (From NewspaperSG). It is not known exactly why Robinson had advocated for 20 minutes, instead of Guillemard’s earlier proposal of 30 minutes. A possible reason, though speculative, would be to compromise between the longitudinal positions between the two Straits Settlements of Penang and Singapore. As reported earlier in 1920, those who opposed Guillemard’s proposal had proposed a 15-minute advancement instead since “Penang was 14½ minutes ahead of Singapore”. See “Legislative Council,” Straits Times, 6 September 1920, 9. (From NewspaperSG). In other words, Robinson’s proposal to advance the time by 20 minutes was probably an amendment of Guillemard’s earlier proposal to cater for the actual difference between Singapore and Penang’s local solar time. The earlier standardisation of time to GMT+07:00 in 1905 already meant that Penang was ahead of its solar time by approximately 20 minutes. The accounting of local solar time, based on longitudinal positions, is probably also one of the reasons why the far-flung islands of Labuan and Christmas Island were explicitly mentioned to be excluded from this ordinance, other than the fact that these islands were not as densely populated to begin with. ↩

-

“Daylight Saving,” Straits Budget, 4 November 1937, 2. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Malayan Time May Be Advanced 10 Minutes,” Straits Times, 5 May 1941, 8; “Colony Time May Be Advanced,” Straits Times, 31 May 1941, 11; “Malayan Time to Be Advanced Next Week,” Straits Times, 26 August 1941, 11; “Further 10 Mins. Daylight Saving,” Malaya Tribune, 27 August 1941, 3. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Daylight Saving Unsatisfactory,” Morning Tribune, 1 September 1941, 6. (From NewspaperSG); “Malayan Time May Be Advanced 10 Minutes.” ↩

-

Wong, “Time Is Just a Man-Made Concept”; Tan Sai Siong, “Time Will Tell on You,” Straits Times, 19 March 1999, 6. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

On the question of the nature of time, see Joseph Mazur, The Clock Mirage: The Myth of Measured Time (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2020.) (From National Library Singapore, call no. R 529 MAZ); Jo Ellen Barnett, Time’s Pendulum: The Quest to Capture Time – From Sundials to Atomic Clocks (New York: Plenum Trade, 1998). (From National Library Singapore, call no. R 529.7 BAR); David S. Landes, Revolution in Time: Clocks and the Making of the Modern World (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2000). (From National Library Singapore, call no. R 681.11309 LAN); Duncan Steel, Marking Time: The Epic Quest to Invent the Perfect Calendar (New York: Wiley, 2000). (From National Library Singapore, call no. R 529.309 STE); Mohammad Ilyas, Global Time System: The Natural Approach (Kuala Lumpur: IIUM Press, Research centre, International Islamic University Malaysia, 2001). (From National Library Singapore, call no. R 529.327 MOH). There is also much to be said about the difference between Greenwich Mean Time (GMT) and Universal Coordinated Time (UTC), but that would call for another article in time. ↩