Singapore Men of Science and Medicine in China (1911–1949)

Wayne Soon sheds light on the enduring and underrated legacy of Overseas Chinese doctors such as Lim Boon Keng and Robert Lim on China’s medical institutions.

Despite being away from China, many Overseas Chinese such as Dr Lim Boon Keng, still contributed to the development of their homeland in one way or another. A group photograph of the first Straits Chinese British Association's committee. (Back row, from left: Seah Eng Kiat, Lim Boon Keng, Chia Keng Chin, Tan Boo Liat, Tan Hap Seng and Wee Theam Tew. Front row, from left: Ong Kew Hoe, Chan Chun Fook, Tan Chay Yan, Song Ong Siang (Honorary Secretary), Tan Jiak Kim (President), Seah Liang Seah (Vice-President), Lee Cheang Yee and Wee Kim Yam (1900)). Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Despite being away from China, many Overseas Chinese such as Dr Lim Boon Keng, still contributed to the development of their homeland in one way or another. A group photograph of the first Straits Chinese British Association's committee. (Back row, from left: Seah Eng Kiat, Lim Boon Keng, Chia Keng Chin, Tan Boo Liat, Tan Hap Seng and Wee Theam Tew. Front row, from left: Ong Kew Hoe, Chan Chun Fook, Tan Chay Yan, Song Ong Siang (Honorary Secretary), Tan Jiak Kim (President), Seah Liang Seah (Vice-President), Lee Cheang Yee and Wee Kim Yam (1900)). Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.Historically the Overseas Chinese – defined as people of Chinese descent or birth who live most of their lives outside of China — were generally thought of as successful merchants and entrepreneurs, as coolies who toiled in mines, plantations, railways and farms in Malaya, Indonesia, Australia, the United States and Cuba, or as tax farmers who collected revenue on behalf of the European colonial authorities.1 Over time, many of such Overseas Chinese carved a livelihood for themselves and assimilated into the cultural and social mores of their adopted countries. As a result, such Chinese have generally been perceived as being much less interested in the affairs of China, especially beyond the focal point of the 1911 revolution when many Overseas Chinese participated in the establishment of the new republic of China.2 Indeed, to those Chinese living abroad at that time, the Chinese in China reminded them of the “Qing officials from whom so many emigrants [had] been glad to escape [from].”3

Yet, many Overseas Chinese returned to work and live in China, often occupying the highest echelons of leadership in various institutions in the first half of the 20th century. They range from Penang-born Gu Hongming who became the standard-bearer for conservative intellectual currents at Peking University to Singapore-born Wu Tingfang who briefly became the Premier of the Republic of China. Even Tan Kah Kee, whose businesses were largely based in Southeast Asia, was actively involved in setting up schools in Xiamen.

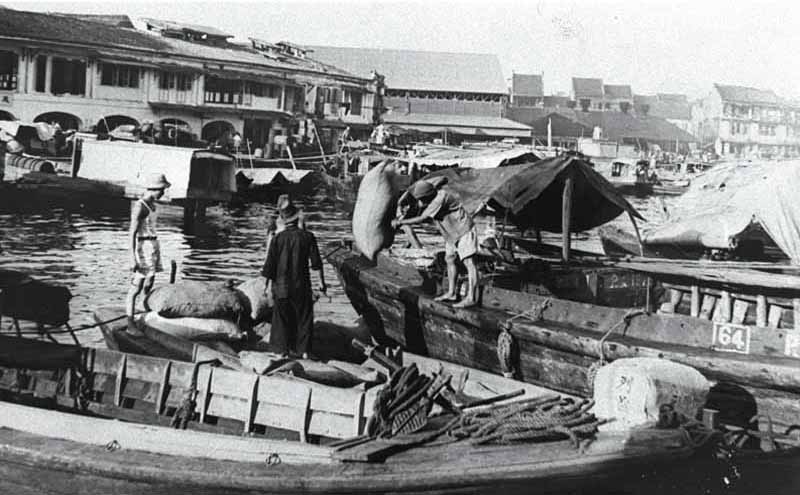

Coolies, commonly found transporting goods along the Singapore River, formed part of the Overseas Chinese community (1948). Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Coolies, commonly found transporting goods along the Singapore River, formed part of the Overseas Chinese community (1948). Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.Among these individuals were educated professionals who promoted and instituted Western science and medicine in modern China,4 including Singapore-born Lim Boon Keng (林文慶 1869–1957) and Robert Lim Ko-Sheng (林可勝 1897–1969).5 This article focuses on the lesser-known aspects of their time spent in China, which not only broadens the study of the Chinese diaspora in Southeast Asia but also highlights the history of science, medicine and technology in China and Southeast Asia.

Lim Boon Keng: Advocate for Science and Confucianism

Lim Boon Keng was the first ethnic Chinese in Singapore to win the Queen’s scholarship in 1887. He studied medicine at the University of Edinburgh from 1888 to 1892. Lim’s education at Edinburgh was comprehensive: he attended classes on botany, anatomy, practical physiology, institute of medicine, pathology, surgery and clinical medicine, among several other classes.6 He graduated with first-class honours, the only one out of 204 students who graduated that year. Even though Lim did not enroll in public health classes at the University of Edinburgh, he would later use British texts in public health to establish health services for the new Republic of China in 1911.

Dr Lim Boon Keng at age 40 in 1909. Ena Teh Guat Kheng collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore

Dr Lim Boon Keng at age 40 in 1909. Ena Teh Guat Kheng collection, courtesy of National Archives of SingaporeInterestingly, Lim sought to integrate his eclectic views of Confucianism with the tenets of modern Western medical science.7 Lim was a strong proponent of Western medical sciences in China and Southeast Asia. As early as 1897, he introduced the origins and vectors of diseases to readers across Europe and Southeast Asia in an 1897 article entitled “Infectious diseases and the public,” published in the Straits Chinese Magazine and read by the English-speaking Chinese diaspora throughout China and Southeast Asia. Lim argued that modern medical science (in the form of physics, chemistry and biology) refuted traditional Chinese understanding that miasma (or “bad air”), and not bacteria and viruses, spread diseases.8 Lim cited British surgeon Joseph Lister and German bacteriologist Robert Koch, who were both known for their contributions to the study of bacteriology and tuberculosis respectively.

Koch had presented his findings on the tubercule bacillus, which causes tuberculosis, at the Berlin Physiological Society on 24 March 1882.9 Less than five years later, a Chinese doctor trained at the University of Edinburgh published Koch’s research halfway across the globe. Clearly, Lim kept pace with the latest changes in the fields of science and hygiene and was eager to share these radical new ideas through the Straits Chinese Magazine.

The “Renovation” of China

Lim believed that the introduction of such cutting-edge modern science and medicine would lead to the “renovation of China.” Yet, this promise of a renaissance was not merely contingent on the introduction of new ideas, more schools, better teachers and hardworking students. What was needed was the invalidation of traditional Chinese medical notions of “wind” and “water” and their effect on the human body so that Western medical ideas could take root in the Chinese mind.10 Lim felt that dispelling these superstitions would come with the acknowledgement of Confucianism as the national religion of the Chinese, a religion based on rationality and acknowledgement of God.11 “When faithfully carried out and supported by a modern course of liberal education,” Lim concluded, “Confucianism [would then become the] ideal religion for which the thinking and critical world is seeking.”12

Besides writing extensively on the importance of Science and Confucianism in the Straits Chinese Magazine, and later in Principles of Confucianism (1912), Lim took steps to translate his beliefs into action. Lim believed in an all-rounded education that included the study of sciences for female students. To this end he founded the Singapore Chinese Girls’ School in 1899. That same year, in his work at the Legislative Assembly, he actively supported the formation of a school of tropical medicine in Singapore.13 He was also an advocate for public health works in Singapore and a strong supporter of the King Edward VII Medical College (which later became the National University of Singapore Medical School).14

Lim’s advocacy also reached China. In 1911, Dr Sun Yat Sen, the first Provisional President of the Republic of China, appointed Lim to head the first Department of Health in the new Republic. After the dissolution of the Provisional Government in Nanjing, Lim left for Beijing to become the Inspector-General of Hospitals under Yuan Shikai’s government where he published his second Chinese book, Elements of Popular Hygiene (1912).15 Based on British doctor E.S. Reynolds’s Primer of Hygiene, the only surviving copy of Lim’s book is found at the National Library of Singapore. Distributed in Beijing and Singapore, the lectures in this handbook were divided into 11 chapters covering topics such as the causes of disease; origins of bacteria; necessities for proper food preparation; design of modern buildings and furniture that facilitate hygienic living; and development of a modern public health system. Popular Hygiene was envisioned as a programmatic handbook to help reshape Beijing according to British standards of weisheng (hygiene).

Lim continued his involvement in China when he was appointed as the President of Xiamen University (also known as Xiada) in 1921 by his close friend, Tan Kah Kee. There, Lim unequivocally supported the growth of the sciences. In a 1922 report on the university, Lim stated that the entire efforts of the college in recent years had been to promote scientific research, with the goal of establishing a comprehensive “Tan Kah Kee College of Science” (Chen Jiageng Kexueyuan 陳嘉庚科學院) to conduct interdisciplinary research and studies of chemistry, physics, biology, geography and zoology.16 In 1931, Lim singled out the Zoological and Botanical departments of Xiada for their cutting-edge research as well as their ability to attract world-renowned professors.17 The importance of the sciences at Xiada was reflected in the records of a local gazetteer. As noted by the Xiamen Republican-era gazetteer, 73 of the 122 graduates were from Xiada, with 26 of them from the science and engineering departments, making up the largest group among the graduates.18

Lim’s expertise in Western medicine as well as his longstanding commitment in promoting Western science and medicine in China resulted in his taking up leadership positions at new institutions of science and medicine at Xiamen University and the Department of Health at the first republic of China.

Lim’s sense of purpose was founded on his medical education at the University of Edinburgh, his commitment to leverage on transnational resources from Britain, China and the Straits Settlements, and his deep commitment to using his wealth and influence to turn ideas into medical action.

Robert Lim: Like Father, Like Son

Lim Boon Keng’s eldest son, Robert Lim, was also actively involved in the medical development of China. Robert Lim was born in Singapore in 1897 and left with his father at the age of eight to Edinburgh where he completed his secondary education. Lim kept in contact with his father in Xiamen, as well as his other family members in Singapore. He also visited Singapore twice in 1937 and 1949.19 At the age of 17, Lim enrolled in the University of Edinburgh. He obtained his PhD from the university at the age of 23 and subsequently became a lecturer in histology in the physiology department.

In 1923, he was awarded a fellowship by the Rockefeller Foundation in the United States to study at the University of Chicago. There, he studied with famous physiologist Dr A.J. Carlson (1875–1956) and began to research on the physiology of gastric secretion. It was during his stint at the University of Chicago that he began his lifelong research on this topic.

In 1924, Robert Lim received his doctor of science degree from the University of Edinburgh and made a life-changing decision to leave the west for China. He became a professor of physiology at the Peking Union Medical College (PUMC) and was soon promoted to head of department. Lim also worked with other overseas Chinese who headed other departments at the Rockefeller-sponsored institution. These included Penang-born O.K. Khaw and C.E. Lim who led the parasitology and bacteriology departments respectively.

While Lim’s research on the nature of gastric physiology was notable, it was his longstanding commitment to state medicine and military medicine that made an indelible impact on China and Southeast Asia. As early as 1921, he proposed several solutions in the Chinese Student to improve the state of medical education in China.20 He urged doctors to produce a national medical curriculum, comprising translations of Western medical works as well as expositions by local doctors. He also felt that doctors should have a working knowledge of the official language in China (Guan hua 官話) as well as have “complete esprit de corps.” He acknowledged the historical contributions of missionaries in the construction of hospitals in China, and encouraged his foreign friends to do more to aid China’s medical modernisation.

Raising Funds for China

During the Second World War, Lim was appointed by Chiang Kai Shek in 1938 to head the Chinese Red Cross Medical Relief Corps (CRCMRC). Lim and his sympathetic allies embarked on a global effort to raise funds for the organisation, especially among ethnic Chinese in Singapore and Indonesia. As a result, more than 60 percent of the funding for the organisation came from such overseas Chinese communities.21 The Chinese in Singapore organised a dinner and grand mannequin parade to solicit donations for the CRCMRC as well as the St Andrew’s Hospital Sanatorium, advertising the event in the Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser on 4 June 1938. Dinner was priced at Straits dollars $3.50 for diners and $2.50 for non-diners.

In September the same year, local ballroom dancers conducted a ballroom dancing class at the local New World Cabaret to raise funds for the CRCMRC.22 Doing her part in fundraising efforts was ethnic Chinese swimmer Yang Shau King, who went by the moniker “Chinese Venus”. She arrived in Batavia (present-day Jakarta) from Hong Kong and gave swimming demonstrations to raise funds for the CRCMRC.23 Dancing, eating and swimming — activities of local Chinese elites in Singapore and Indonesia — were platforms for fundraising for the CRCMRC and reminiscent of similar efforts in China.24

Entrance of New World Amusement Park at Jalan Besar, circa 1960. This was where Chinese swimmer Yang Shau King helped to raise funds for the Chinese Red Cross. Chinese Clan Association collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Entrance of New World Amusement Park at Jalan Besar, circa 1960. This was where Chinese swimmer Yang Shau King helped to raise funds for the Chinese Red Cross. Chinese Clan Association collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore. Group photograph of Singapore Overseas Chinese raising relief funds for China, headed by Tan Kah Kee. Singapore Chinese Clan Associations Collection, Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Group photograph of Singapore Overseas Chinese raising relief funds for China, headed by Tan Kah Kee. Singapore Chinese Clan Associations Collection, Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.At the CRCMRC, Robert Lim greatly expanded medical care for the wounded Chinese in the form of preventive medicine for unoccupied China. One key aspect of preventive medicine was delousing, which killed parasitic mites and lice on soldiers. The mites spread scabies, the number one affliction of Chinese soldiers then.25 Scabies was a serious condition as soldiers would scratch their wounds into a secondary and more serious skin infection known as impetigo, a highly contagious bacterial infection. Typhus fever and relapsing fever were spread by lice, with the former being more serious, often leading to premature death if not treated expeditiously. These conditions were often exacerbated by the lack of access to bathing water and soap, which meant mites and lice would remain with their hosts for long periods of time.

The delousing programme began in 1938 and expanded significantly in 1939. Trained sanitary engineers and doctors in mobile units were sent across unoccupied China to delouse soldiers and their clothes. By mid-1939, mobile units had reached as far east as Jinhua (金華) in Zhejiang, as far west as Chongqing (重慶), as far north as Ganguyi (甘谷驛) in Shanxi, and as far south as Liuzhou (柳洲) in Guangxi.26 By the mid-1940s, mobile units had reached further south to Nanning (南寧) in Guangxi and further west to Xiaguan (下關) in Yunnan.27 The reach of the delousing units spread far and wide as it attempted to extend treatment to all soldiers in unoccupied China. In total, the sanitary units deloused a total of around 380,000 people as well as 800,000 articles by the end of December 1940, an exponential increase from January to June 1939 where around 17,000 persons and 145,000 thousand articles were deloused. In total, Lim’s CRCMRC treated more than five million people.

Leaving a Legacy

Lim Boon Keng and Robert Lim’s time in China were not without opposition. Lu Xun and other intellectuals from the May Fourth Movement (1917–1921) opposed Lim Boon Keng’s promotion of sciences and Confucianism at Xiamen University. Unable to resolve their differences with him, these intellectuals left the university after teaching for only a few months.28

American officials from the United China Relief (UCR) organisation allegedly sought to remove Robert Lim from his medical leadership posts because of their opposition to the supposedly obstructionist and monopolistic behaviours of the American Bureau for Medical Aid to China (a New York-based organisation also known as ABMAC), which Lim represented in China.29 Other accounts suggest that some Chinese leaders opposed Lim’s plan to extend medical aid to communist-held areas. These critics also thought his six-year medical programme for doctors was too lengthy under wartime circumstances.30

As a result of these pressures, Robert Lim left his position as the head of the Emergency Medical Services Training School (EMSTS) in 1942, but soon took on the role of chief medical officer in the Chinese Expeditory Forces. He also embarked on a tour of the US in 1944 that sought to boost medical contributions by Americans to the Chinese war effort. He held the position of surgeon-general of the Chinese Army (1945–1948) and founded the National Defense Medical Center (NDMC) in Shanghai in 1948, which remains an important institution of military medicine in Taiwan today.

Besides Lim Boon Keng and Robert Lim, there were other prominent Overseas Chinese who were instrumental in promoting western medicine in China: Wu Lien-teh of the North Manchurian Plague Prevention Services (NMPPS) and National Qurantine Bureau (NQS); O.K. Khaw of the Peking Union Medical College and NDMC; C.E. Lim of the PUMC; and C.Y. Wu of the NMPPS, NQS and CRCMRC.

Of particular importance was Penang-born Wu Lien-teh, who was a Queen’s scholar at Cambridge University. Wu was most famous for his discovery of an unknown disease (later found to be the pneumonic plague) that wreaked havoc across North China in the 1910s, as well as his role in the expansion of the Western-style public health system in the region. After heading the NMPPS from 1912 to 1930, he left North China to head the Shanghai-based NQS and established a comprehensive system of quarantine, fumigation and health inspections in ports such as Shanghai, Hankou and Xiamen.31

Wu, together with the Lims and the other Overseas Chinese, represent an unsung group of medical diaspora who returned to work in China. These medical professionals facilitated the growth of medical and scientific research in China, and popularised new notions of Western science among the Chinese public. In addition, they instituted military medicine, introduced new forms of public health and sought to save lives during the Second World War. As medical professionals, they were not simply motivated by patriotism or altruism, but rather saw China as a place where they could fully utilise their expertise not only to improve the lives of their fellow Chinese, but also to advance their own careers as medical leaders of the new Republic.

Wayne Soon was a Lee Kong Chian Research Fellow at the National Library and is currently a PhD candidate in the History Department at Princeton University. His dissertation examines the history of Western medicine in China, with a focus on the new medical institutions created by Overseas Chinese doctors in China during the first half of the 20th century.

REFERENCES

5th report of the Chinese Red Cross Medical Relief Corps. Lim’s papers, IMH archives.

7th report of the Chinese Red Cross Medical Relief Corps, Lim’s papers, IMH archives, 2307001, 194.

Brock, T. D. (1999). Robert Koch: A life in medicine and bacteriology (p. 117). Washington, D.C.: ASM Press. (Not available in NLB holdings)

Chen, J.Y. (2012). Guilty of indigence: The urban poor in China, 1900–1953 (pp. 189–190). Princeton, NJ.: Princeton University Press. (Call no.: 305.5690951091732 CHE)

Chinese venus arrives at Batavia. (1938, July 24). The Straits Times, p. 5. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Corfield, J. (2010). Historical dictionary of Singapore. Lanham, MD: Scarescrow Press. (Call no.: RSING 959.57003 COR)

In folder Alfred Kohlberg original memo and Alfred Kohlberg second report. American Bureau for Medical Aid to China Records, Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Columbia University in the city of New York.

Kuhn, P.A. (2008). Chinese among others: Emigration in modern times. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield. (Call no.: RSEA 304.80951 KUH)

Lim, B.K. (1897, December). Infectious diseases and the public. The Straits Chinese Magazine, 1 (7), 120–124.

Lim, B.K. (1898, September). The renovation of China. The Straits Chinese Magazine, 2 (7), 88–98.

Lim, B.K. (1931). On the tenth anniversary of the founding of Amoy University. (Unknown publisher). (Not available in NLB holdings)

Lim, R. (1921, November). The medical needs of China. Chinese Student, 24–25.

Lin, Y., Liu, Z., & Bian, Y. (1991). Lin Yutang zi zhuan [Lin Yutan’s autobiography] (pp. 98–100). Shijiazhuang Shi: Hebei renmin chubanshe. (Not available in NLB holdings)

林文庆 [Lin, W.Q.]. (1911). 普通卫生讲义 [Pu tong wei sheng jiang yi]. Xin jia po: Xin jia po hua zhong shang wu zong hui cai zheng suo. (Call no.: RRARE 613 LBK)

Lin, W.X.B. (1987). Xiamen daxue xiaoshi bianweihui, Xiamen daxue xiaoshi ziliao (pp. 224–229). Xiamen: Xiamen daxue chu ban she. (Not available in NLB holdings)

National Archives at Kew. (1899, February 14). Annual Department Reports, Colonial Office 279/59. Retrieved from National Archives at Kew.

Page 4 Advertisements Column 2: Cabaret. (1937, September 18). The Straits Times, p. 4. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Seven reports of the Chinese Red Cross Medical Relief Corps, Lim’s Papers. IMH Archives.

Wakeman, F.E. (2003). Spymaster Dai Li and the Chinese secret service (p. 389). Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. (Not available in NLB holdings)

Xiamen Shi defang zhi bian zuan weiyuan hui, Xiamen shi zhi: Mingguo (Xiamen Gazetteer: Republican Period) (Beijing: Fangzhi chubanshe, 1999), 331 and 361–67.

Xun, L. (1981). Hai shang tong xin [Maritime communications] (pp. 158–161). In Lu Xun quanji [Complete works of Lu Xun]. Beijing: Renmin wenxue. (Not available in NLB holdings)

Yip, K-C. (1995). Health and national reconstruction in nationalist China: The development of modern health services, 1928–1937 (pp. 117–120). An Arbor, MI: Association for Asian Studies. (Call no.: R 362.1095109043 YIP)

NOTES

-

Kuhn, P.A. (2008). Chinese among others: Emigration in modern times. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield. (Call no.: RSEA 304.80951 KUH) ↩

-

For a survey of the Overseas Chinese’s efforts at supporting the 1911 revolution in China. See Lee, L.T., & Lee, H.G. (Eds.). (2011). Sun Yat-Sen, Nanyang, and the 1911 revolution. Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. (Call no.: RSING 951.036 SUN) ↩

-

This is not to say there is nothing on the overseas Chinese in China. What has been neglected, however, is the importance of their diasporic identities. For example, Karl Gerth points out the importance of Wu Tingfang, a Chinese elite educated in the West, in mobilizing the Chinese population in Shanghai and Nanjing to boycott Japanese-made products in favour of Chinese-produced ones. Similarly, Klaus Muhlhahn showed how Wu overhauled the criminal justice system after the fall of the Qing dynasty in 1911. Wu drew up a new legal system for the Republic of China based on the synthesis of Western laws and Chinese traditions. The new system abolished flogging, introduced professional judges and western-style lawyers, and limited punishments to fines, jail and the death penalty. Both Gerth and Muhlhahn however, did not mention that Wu was also an Overseas Chinese. Wu’s experiences growing up in colonial Singapore and Hong Kong, as well as his legal education the University College London, enabled Wu to understand the intricacies of Western laws and Chinese tradition. These experiences and education allowed Wu to occupy critical positions in the new Republic. See Gerth, K. (2003). China made: Consumer culture and the creating of the nation. Cambridge, MA.: Harvard University Press. (Call no.: RBUS 339.4709510904 GER) and Muhlhahn, K. (2009). Criminal justice in China: A history. Cambridge, MA.: Harvard University Press. (Call no.: R 364.951 MUH) ↩

-

Another key individual was Wu Lien-Teh (伍連德 1879–1960), who was instrumental in instituting western medicine in Manchuria and Shanghai from 1911–1937. He was famous as the plague fighter who combated the outbreaks of plague, cholera, and other communicable diseases in North China. ↩

-

Lim Boon Keng Matriculation File for the Department of Medicine, University of Edinburgh Student Records, University of Edinburgh. ↩

-

See for example Li, Y. (1991). 林文庆的思想 : 中西文化的汇流与矛盾 = The thought of Lim Boon Kong: Convergency and contradiction between Chinese and western culture. Xinjiapo: Xinjiapo Ya Zhou yan jiu xue hui. (Not available in NLB holdings) ↩

-

Lim, B.K. (1897, December). Infectious diseases and the public. The Straits Chinese magazine, 1 (7), 120–124. ↩

-

Brock, T. D. (1999). Robert Koch: A life in medicine and bacteriology (p. 117). Washington, D.C.: ASM Press. (Not available in NLB holdings) ↩

-

Lim, B.K. (1898, September). The renovation of China. The Straits Chinese magazine, 2 (5), 88–98. ↩

-

Lim Boon Keng drew his ideas of Confucianism as state religion for the Chinese, and the idea of Confucian as a god-like figure from prominent Late Qing reformer Kang Youwei. For an explanation of Kang’s ideas on Confucianism as a state religion, see Chen, Y. (2013). Confucianism as religion: Controversies and consequences (pp. 43–53). Leiden: Brill. (Call no.: R 299.513 CHE) ↩

-

National Archives at Kew. (1899, February 14). Annual Department Reports, Colonial Office 279/59. Retrieved from National Archives at Kew. ↩

-

Corfield, J. (2010). Historical dictionary of Singapore. Lanham, MD: Scarescrow Press. (Call no.: RSING 959.57003 COR) ↩

-

林文庆 [Lin, W.Q.]. (1911). 普通卫生讲义 [Pu tong wei sheng jiang yi]. Xin jia po: Xin jia po hua zhong shang wu zong hui cai zheng suo. (Call no.: RRARE 613 LBK) ↩

-

Lin, W.X.B. (1987). Xiamen daxue xiaoshi bianweihui, Xiamen daxue xiaoshi ziliao (pp. 224–229). Xiamen: Xiamen daxue chu ban she. (Not available in NLB holdings) ↩

-

Lim, B.K. (1931). On the tenth anniversary of the founding of Amoy University. (Unknown publisher). (Not available in NLB holdings) ↩

-

Xiamen Shi defang zhi bian zuan weiyuan hui, Xiamen shi zhi: Mingguo (Xiamen Gazetteer: Republican Period) (Beijing: Fangzhi chubanshe, 1999), 331 and 361–67. A total of 2013 students graduated from Xiada until 1947. In 1947, there were around 3,000 teachers and 1,227 students in Xiada, with the majority of the students in the science, technical and law departments. ↩

-

Lim briefly visited his place of birth in 1937 and 1949, and wrote to his Singaporean relatives in the 1960s. See “Malayan Broadcasting interview with Robert Lim, July 14, 1949”, and “Lim to Thiam, July 25 1964”, in Robert Lim’s Papers, Institute of Modern History Archives, Academia Sinica, Taipei, Taiwan (hereafter Lim’s Papers, IMH archives). ↩

-

Lim, R. (1921, November). The medical needs of China. Chinese Student, 24–25. ↩

-

Seven reports of the Chinese Red Cross Medical Relief Corps, Lim’s Papers. IMH Archives. ↩

-

Page 4 Advertisements Column 2: Cabaret. (1937, September 18). The Straits Times, p. 4. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Chinese venus arrives at Batavia. (1938, July 24). The Straits Times, p. 5. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Janet Chen describes similar efforts in Shanghai where elites would raise funds for Subei refugees right after the war through organising beauty pageants and dance parties. Critics claimed that such efforts reflected the hedonistic lifestyle of the Shanghai elites, even though they appeared extraordinarily successful in raising funds for relief efforts. See Chen, J.Y. (2012). Guilty of indigence: The urban poor in China, 1900–1953 (pp. 189–190). Princeton, NJ.: Princeton University Press. (Call no.: 305.5690951091732 CHE) ↩

-

5th report of the Chinese Red Cross Medical Relief Corps. Lim’s papers, IMH archives. ↩

-

Ibid, 135. ↩

-

7th report of the Chinese Red Cross Medical Relief Corps, Lim’s papers, IMH archives, 2307001, 194. ↩

-

Xun, L. (1981). Hai shang tong xin [Maritime communications] (pp. 158–161). In Lu Xun quanji [Complete works of Lu Xun]. Beijing: Renmin wenxue. (Not available in NLB holdings); Also see Lin, Y., Liu, Z., & Bian, Y. (1991). Lin Yutang zi zhuan [Lin Yutan’s autobiography] (pp. 98–100). Shijiazhuang Shi: Hebei renmin chubanshe. (Not available in NLB holdings) ↩

-

In folder “Alfred Kohlberg Original Memo” and “Alfred Kohlberg Second Report”, American Bureau for Medical Aid to China Records, Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Columbia University in the city of New York. ↩

-

American Bureau for Medical Aid to China Records, Rare Book & Manuscript Library; Wakeman, F.E. (2003). Spymaster Dai Li and the Chinese secret service (p. 389). Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. (Not available in NLB holdings) ↩

-

Yip, K-C. (1995). Health and national reconstruction in nationalist China: The development of modern health services, 1928–1937 (pp. 117–120). Ann Arbor, MI: Association for Asian Studies. (Call no.: R 362.1095109043 YIP) ↩