Fire Dragon Blazes Trail for Cantonese Temple in Geylang

Mun San Fook Tuck Chee Temple is the home of the Fire Dragon in Singapore.

By Angela Sim

Dragons are known to breathe fire, but one particular dragon, seen every three years in Singapore, does something even more dramatic – it eventually becomes engulfed in flames.

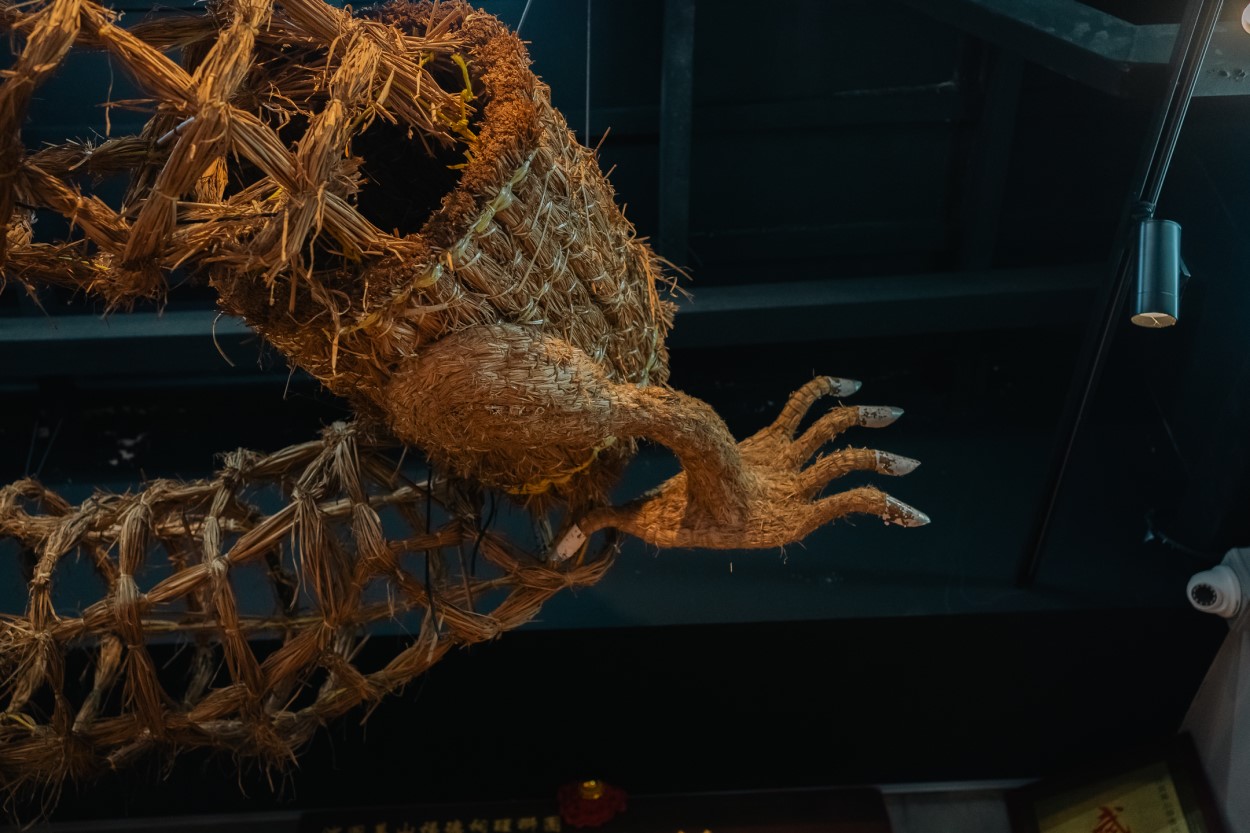

The Straw Fire Dragon (稻草香火龍) has a body that is made from straw wrapped around a rattan frame. The head and body of the dragon bristle with lit joss sticks that eventually set the entire dragon on fire, ending the performance.

This particular dragon dance is only performed once every three years, on the second day of the second lunar month to celebrate the birthday of the Earth Deity or Tu Di Ye Ye (土地爷爷). It is organised by the Sar Kong Mun San Fook Tuck Chee Temple (沙岡萬山福德祠) in Sims Drive in Geylang. The Fire Dragon dance originated in Guangdong province in China, and the temple decided to perform this dance in the late 1980s.1

A Fire Dragon at the Sar Kong Heritage Room, 2023. Courtesy of Edmund Lau.

A Fire Dragon at the Sar Kong Heritage Room, 2023. Courtesy of Edmund Lau.The Making of a Dragon

The first Fire Dragon that the temple made was a simple one. It was made of “banana fronds and paper for the head”. Chin Fook Siang, the chairman of the Mun San Fook Tuck Chee Temple, recalled that it cost $2,400 to produce. The money came from funds that were pooled together thanks to small donations from the temple’s patrons – “just 20 cents, 30 cents, or 50 cents only” – and generous contributions from Chin himself and two other temple committee members. The reason why the temple decided to make a Fire Dragon has unfortunately been lost to time.

The Fire Dragon’s first performance was in 1989, on the 15th day of the eighth lunar month. After conferring with the temple elders, the then-Chairman of the temple (who was also the owner of Tiger Brand soy sauce) invited the Fire Dragon (or rather, the presence of the deity) into the temple. Since then, the temple has taken on the responsibility of continuing the Fire Dragon dance.

Creating the dragon is a painstaking, tedious process – just constructing the head alone can take up to two months while the whole dragon from head-to-claws can take almost half a year. There are only two craftsmen in Singapore who can make the dragon – Fong Keng Yan (冯景源) and Zhen Meng Chye (甄明仔). Fong had travelled to Hetang, Xinhui County in China’s Guangdong Province to learn the art of making the fire dragon. Zhen, in turn, picked up his skills by observing Fong at work on the temple grounds.

Fong Keng Yan working on a dragon frame. Courtesy of Man San Fook Tuck Chee.

Fong Keng Yan working on a dragon frame. Courtesy of Man San Fook Tuck Chee. Zhen Meng Chye attaches bunches of straw to the rattan frame with a metal hook, 2023. Courtesy of Edmund Lau.

Zhen Meng Chye attaches bunches of straw to the rattan frame with a metal hook, 2023. Courtesy of Edmund Lau. Close-up of the rattan frame and straw for the antlers, 2023. Courtesy of Edmund Lau.

Close-up of the rattan frame and straw for the antlers, 2023. Courtesy of Edmund Lau. Detail of the bundles of straw sewn together, 2023. Courtesy of ANTZ.

Detail of the bundles of straw sewn together, 2023. Courtesy of ANTZ. Sewing of dried straw to form the dragon, 2023. Courtesy of Edmund Lau.

Sewing of dried straw to form the dragon, 2023. Courtesy of Edmund Lau. Close-up of string used to sew the straw together, 2023. Courtesy of Edmund Lau.

Close-up of string used to sew the straw together, 2023. Courtesy of Edmund Lau.The straw that is used for the dragon is specially obtained from farmers in Xiamen, China. “They do not charge us a fee, but we do provide gratuity for the labour as well as arrange for the dried straw to be packed into a container, then shipped to Singapore,” said Chin. “It is a tedious process, but it has to be done as Singapore doesn’t have paddy fields to produce dried straw for us to use.” To prevent the straw from disintegrating due to Singapore’s heat, it is sprayed with water when in storage.

The younger members of the dragon dance troupe help to construct the body of the dragon, while Fong and Zhen take on the more difficult tasks of crafting the dragon’s head and tail.

Securing the straw to the head of the dragon requires skill. A needle in the shape of a metal hook is used to secure the bunches of straw to the frame of the dragon’s head. Zhen has a special technique for sewing on the straw. “Just like a seamstress or a tailor who has a method to work with, I have a method which I have adopted to sew the straw,” he said. “It’s not easy as I need to ensure the right tension is used so that the straw will not unravel during the dance of the Fire Dragon.”

Making the antlers of the dragon is particularly challenging because it requires pulling excess straw into “the ends of the antlers of the dragon”, cutting and then tucking them back into themselves to make clean, sharp edges. “Making it neat and looking sharp takes years of skill,” said Zhen.

Some parts of the dragon’s head, like its mouth and teeth, are made by attaching a base layer of gauze, with paper layered on. Colour is added after the layers dry. Other parts are fashioned out of painted paper and wood cut-outs. The eyes of the dragon are made from plastic light bulbs.

Wire was previously used to secure the rattan together to make the frame, but the wire would cut Zhen’s hands and fingers, so they switched to plastic cable ties instead, which was also faster and easier to use.

Changes in the quality of rattan have also presented challenges for the dragon-makers. The rattan they receive is already stripped of its bark, which makes it less malleable, and a lot of effort and a longer time is needed to get it to bend. To use it, the rattan must first be soaked in water to make it more flexible. A hairdryer is then used to heat up spots to bend the rattan into the desired shape.

Details of the dragon’s eyes, 2023. Courtesy of Edmund Lau.

Details of the dragon’s eyes, 2023. Courtesy of Edmund Lau. The dragon’s snout, 2023. Courtesy of Edmund Lau.

The dragon’s snout, 2023. Courtesy of Edmund Lau. Claws of the dragon with metal nail tips, 2023. Courtesy of Edmund Lau.

Claws of the dragon with metal nail tips, 2023. Courtesy of Edmund Lau.Dance of the Dragon

Once the entire dragon has been constructed, all that is left is the performance. Before the procession begins, more than 4,000 lit joss sticks are inserted into the body of the dragon, from head to tail. These joss sticks, which are thicker than the usual ones used for prayers at the temple, must be properly embedded in the dragon to ensure no one gets hurt when the Fire Dragon comes alive during the dance ritual. Inserting the joss stick into the tightly packed straw requires some force.

A devotee carefully inserting a lit joss stick into the dragon, 2023. Courtesy of Yeo GT.

A devotee carefully inserting a lit joss stick into the dragon, 2023. Courtesy of Yeo GT. Devotees inserting lit joss sticks into the dragon before the procession, 2023. Courtesy of Yeo GT.

Devotees inserting lit joss sticks into the dragon before the procession, 2023. Courtesy of Yeo GT. A section of the body with lit incense, 2023. Courtesy of Yeo GT.

A section of the body with lit incense, 2023. Courtesy of Yeo GT. Joss sticks adorning the pearl of wisdom, 2023. Courtesy of Yeo GT.

Joss sticks adorning the pearl of wisdom, 2023. Courtesy of Yeo GT.The Fire Dragon, at more than 60 m long and festooned with thousands of burning joss sticks, is a striking sight as it manoeuvres through the smoke. The parade of the dragon begins in the temple before going through the nearby streets. The procession is believed to help dissipate anger caused by the disturbance of the land around the temple felt by the temple’s deities.

The dragon is brought to life by about 80 to 100 dancers (including fire throwers) from the temple’s lion dance troupe, which was established in 1983. Weighing in at a total of 65 kg, the dragon is exhausting to perform with – just the head alone requires three dancers who take turns to hold it up.

The joss sticks take between three and four hours to burn through, which means the performance will need to be concluded by that time. Eventually, the lit joss sticks burn to the point where they are buried into the straw and the straw catches fire. At that point, the dragon is left to rest on the ground to be devoured by the flames. The Fire Dragon ends its sojourn in this world surrounded by smoke and fire, ascending to the heavens bearing the wishes and prayers of its devotees. When the time comes for the next performance, an invitation ritual must be held to invite the dragon to descend from the heavens once again.

The Fire Dragon parading down Sims Drive, 2023. Courtesy of Yeo GT.

The Fire Dragon parading down Sims Drive, 2023. Courtesy of Yeo GT. The Fire Dragon in flames, c.1990s. Courtesy of Mun San Fook Tuck Chee.

The Fire Dragon in flames, c.1990s. Courtesy of Mun San Fook Tuck Chee.The Sar Kong Mun San Fook Tuck Chee Temple

Although the Fire Dragon dance was first performed in the temple in 1989, it was performed irregularly until 2015 when the temple celebrated its 150th anniversary. Since then, the temple has put up the performance in the neighbourhood every three years. However, outside that schedule, they have also performed during the Chingay parade, most recently in 2024.

The Sar Kong Mun San Fook Tuck Chee Temple was established during the early 1860s according to an inscription on a stele that dates back to 1901. The temple was originally located in the Kallang Basin and its name, Sar Kong, meaning “sand dune”, was the name of a village there. The village got its name from sandy deposits in the area that attracted the earliest brick kiln operators to set up their kilns in the vicinity.2 The temple moved to its present site at Sims Drive in 1901.3

The Sar Kong Mun Fook Tuck Chee Temple at Sims Drive, 2007. Courtesy of Ang Yik Han.

The Sar Kong Mun Fook Tuck Chee Temple at Sims Drive, 2007. Courtesy of Ang Yik Han. The temple was originally located in the Kallang Basin, 2007. Courtesy of Ang Yik Han.

The temple was originally located in the Kallang Basin, 2007. Courtesy of Ang Yik Han.The main deity worshipped at the temple is Tu Di Gong (also known as the Earth Deity, Tu Di Ye Ye, Toh Teh Ye Ye or Bo Gong), likely due to the numerous brick kilns in the area. The workers of these kilns were either Cantonese or Hakka, and they brought their custom of worshipping Tu Di Gong along with them.4 As a mark of respect to Tu Di Gong, prayers were routinely offered prior to the firing of the kilns. The birthday celebration of this deity, which falls on the second day of the second lunar month, is the most important occasion in the temple’s calendar of events.

A few lesser-known deities are also worshipped at the temple, which is known as a Cantonese temple. One such deity is Jin Hua Fu Ren (金花夫人 or Kam Fa Leung Leung), a female deity unique to the Cantonese. She is a protector of women and a goddess of fertility and childbirth. The deities Hua Gong Hua Po (花公花婆 or Fa Kung Fa Po) are Jin Hua Fu Ren’s subordinates who are in charge of matrimony and childbirth.

Jin Hua Fu Ren also has assistant or attendant deities, known as Shi Er Nai Niang (十二奶娘). These are 12 nannies who bless children, and women for fertility, conception and smooth deliveries. Women praying to conceive children often tie red strings onto the infants held by these nannies.

Jin Hua Fu Ren and her two attendants, 2008. Courtesy of Ang Yik Han.

Jin Hua Fu Ren and her two attendants, 2008. Courtesy of Ang Yik Han. Hua Gong and Hua Po, 2008. Courtesy of Ang Yik Han.

Hua Gong and Hua Po, 2008. Courtesy of Ang Yik Han. One of Jin Hua Fu Ren’s Shi Er Nai Niang, 2008. Courtesy of Ang Yik Han.

One of Jin Hua Fu Ren’s Shi Er Nai Niang, 2008. Courtesy of Ang Yik Han. Hua Tuo Xian Shi, 2008. Courtesy of Ang Yik Han.

Hua Tuo Xian Shi, 2008. Courtesy of Ang Yik Han.The temple is also home to Hua Tuo Xian Shi (华陀先师 or Wah To), a legendary physician in the Annals of the Three Kingdoms. He is the patron deity of physicians, and many immigrants prayed to him to resolve medical issues in the absence of access to healthcare.

The temple used to be the centre of kampung life. Chin, who is also the Vice-Chairman of the Taoist Federation Singapore, has lived most of his life near the temple. The temple owned much of the land surrounding it, which it rented out.

Chin remembers an idyllic childhood with “everyone sitting outside their houses and chatting in the early evenings when it was too hot to be indoors. [They] were always together beside the river and that was the true kampung spirit.”

A temporary opera stage would be set up across the temple, where opera shows would be staged on temple feast days. The temporary opera stage also provided shelter and a place for Chinese coolies to rest. Chinese migrants who found work at the nearby brick kilns sometimes also slept under the opera stage.

The temple was also active within the community. In 1942, it established Meng Yang School and the Sar Kong Sports Association.5 In fact, the temple’s current historical museum hall was once a sports hall used for table tennis and martial arts practices. The temple also used to have a huge pot to cook plain, white rice, which was distributed to the needy as well as Chinese workers living near the temple. “We just added a pinch of salt to make it more palatable,” said Chin.

In keeping with the temple’s commitment to safeguarding the Fire Dragon, Master Zhen hopes to pass down his knowledge to the next generation. He wants to educate the public about the Fire Dragon and conduct classes for those keen to learn the art form – and in doing so ensure the longevity and legacy of the dragon.

Angela Sim is a researcher of Asian heritage and culture. She uses her platform as a media content creator to explore areas such as folk religion, Peranakan culture, and sunset industries including Chinese woodblock printing, effigy restoration, and lantern making. Angela is a Singapore native and promotes the nation as a cultural destination. She has a Bachelor of Arts majoring in Japanese Art History and currently resides in Brisbane, Australia. Her work can be found on YouTube under the handle Hakka Moi.

Angela Sim is a researcher of Asian heritage and culture. She uses her platform as a media content creator to explore areas such as folk religion, Peranakan culture, and sunset industries including Chinese woodblock printing, effigy restoration, and lantern making. Angela is a Singapore native and promotes the nation as a cultural destination. She has a Bachelor of Arts majoring in Japanese Art History and currently resides in Brisbane, Australia. Her work can be found on YouTube under the handle Hakka Moi.Notes

-

Ang Yik Han 洪毅瀚, Xiang qing ci yun: Shagang Cun he wan shan fu de ci de liu bian yu chuan cheng 乡情祠韵 : 沙冈村和万山福德祠的流变与传承 [A kampong and its temple: Change and tradition in kampong Sar Kong and the Mun San Fook Tuck Chee] (Singapore: 万山福德祠, 2016), 107. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 203.5095957 HYH) ↩

-

Lü Shicong 吕世聪, Tou tao zhi bao: Wanshan Gang Fude Ci li shi su yuan 投桃之报 : 万山港福德祠历史溯源 [A boon returned: The history of Mun San Fook Tuck Chee] (Singapore : 石叻学会, 2008), 44. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 203.5095957 LSC) ↩