Nanjing to Nanyang: Missionary Sojourns to Singapore and Christian Educational Missions in the 1950s

Upheaval in China saw missionaries shifting their sights and resources to Singapore and the region, establishing related institutions and reaching the masses through education.

By Joshua Tan

3 December 2024

In January 1955, two American missionaries, C. Stanley Smith and William P. Fenn, serendipitously met each other in Singapore. Both were previously Protestant missionary professors in Nanjing, the capital city of the Republic of China – Fenn at Nanking University (Jinling Daxue) and Smith at Nanking Theological Seminary. Having been exiled from the original “mission fields” in China, they found themselves in Singapore, working on new missions among Chinese students in the diaspora.

Following the Chinese communist revolution of 1949, many American missionaries like Smith and Fenn, searched for alternative mission fields in Asia where they could redeploy resources and personnel slated for China. In doing so, missionary work in China was now displaced into other regions of East and Southeast Asia, starting with ethnic Chinese communities in the diaspora. The British port-city of Singapore, with its ethnic Chinese majority and the government’s receptiveness to American missionaries and funds, proved to be a fruitful site for the expansion of these “China missions”.1

From Nanjing to Nanyang: Missionary Sojourns from China to Singapore

The large contingent of missionaries departing China – some of whom converged on Singapore’s shores in the early 1950s – was one of the myriad ways that the 1949 Chinese Communist Revolution and an emerging Cold War in Asia unexpectedly shaped local Christian communities. As historian Creighton Lacy notes, out of an estimated 4,000 Protestant missionaries departing China on the eve of the communist takeover, over 2,000 were subsequently redeployed to new mission fields in Asia – particularly in regions such as Japan and the Philippines, with their strong American political influence and receptivity to missionaries.2

In Singapore and Malaya, most of the missionaries who arrived from China were recruited by the colonial government to support the state’s welfare and developmental work in the Malayan New Villages.3 During the Malayan Emergency (1948–60), colonial authorities resettled half a million rural dwellers in Malaya, mainly Chinese, to cut them off from the activities of the Malayan Communist Party.4 At least 400 missionaries from all mission boards were engaged in New Village work, with 111 of them from British missionary societies. In Singapore, specific numbers of missionaries entering the colony in this period are difficult to ascertain, as many passed through briefly either en route to work in the Federation or in Southeast Asia. For instance, the China Inland Mission (CIM), one of the largest groups to relocate its headquarters from Shanghai to Singapore, saw 130 missionaries arriving in Singapore in 1952, although they soon scattered across Southeast Asia.

However, mission work was not simply concerned with the rural Chinese in the New Villages. In fact, some missionaries like Fenn and Smith, with their decades of experience as professors in China, were deeply concerned with supporting the needs of urban Chinese students. Thus, they were also keen to lend their expertise in the area of higher education in Singapore. A survey of the religious landscape of Singapore in the early- to mid-1950s revealed the establishment of several new institutions such as the Singapore Theological Seminary (later the Singapore Bible College), Trinity College (later Trinity Theological College) and the Singapore Catholic Central Bureau, supported by funds redirected from China, expressly to meet the needs of “overseas Chinese” students in Southeast Asia.

Beyond supporting churches, some missionary-funded institutions were deliberately located near secular higher educational institutions to facilitate work with students. Some prominent examples include the Jesuit Hostel (Kingsmead Hall) to serve Malayan students attending the Teachers’ Training College, a Franciscan Institute of Sociology in Bukit Batok (to reach students at Nanyang University) and an ecumenical Protestant Christian Students’ Centre (9–11 Adam Road) adjacent to the University of Malaya’s Bukit Timah campus. In fact, former China missionaries, such as Paul Contento of CIM and the German Franciscan Fr. Guido Goerdes, joined the inaugural faculty of Nanyang University and lived on its Jurong campus, as part of their missionary agenda to monitor communism and spread Christianity.5

The Reverend Father Patrick Joy (standing) was the supervisor of Kingsmead Hall, a student hostel built by the Jesuit Fathers, located near the Teachers’ Training College. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

The Reverend Father Patrick Joy (standing) was the supervisor of Kingsmead Hall, a student hostel built by the Jesuit Fathers, located near the Teachers’ Training College. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore. Missionaries Elisabeth and Paul Contento (left and centre) with University of Malaya Medical Professor Khoo Oon Teik (right). The Contentos, members of the British Evangelical China Inland Mission, are best remembered best for their evangelical affiliations. They lived on the Nanyang University campus in the early 1950s, which they saw as a good way to reach Chinese students overseas. Courtesy of Scripture Union Singapore.

Missionaries Elisabeth and Paul Contento (left and centre) with University of Malaya Medical Professor Khoo Oon Teik (right). The Contentos, members of the British Evangelical China Inland Mission, are best remembered best for their evangelical affiliations. They lived on the Nanyang University campus in the early 1950s, which they saw as a good way to reach Chinese students overseas. Courtesy of Scripture Union Singapore.C. Stanley Smith and Trinity College

C. Stanley Smith was a veteran American missionary and representative of the Board of Founders of Nanking Theological Seminary. As principal of Trinity (Theological) College (1954–56), Smith had an instrumental role in shaping the college into Singapore’s premier ecumenical Protestant seminary.

Trinity College was formally founded in 1948 as a Union College and Training School supported by American Methodist personnel and funding, with nominal representation from Anglicans and English Presbyterians. Plans for a Methodist College and vocational school to support local church workers and lay-Christian leadership were in place before the war. The plan was energised by wartime cooperation among incarcerated British and American missionaries at the Changi Internment Camp. Thus, when the college came to fruition in 1948, among its early cohorts of students were not only seminarians, but a diverse group of students studying both religious and secular subjects.6

Trinity College in the early 1950s did not focus solely on religious education; it was also a training school for teachers. Many of the early graduates of Trinity College believed their mission fields to be middle schools and were often already working part-time as middle school teachers when studying at the college.7 At Trinity’s Chinese Department for instance, which was inaugurated in 1951, only 6 out of 27 students were registered in regular courses in theology – the rest were studying secular subjects, possibly on track to careers as middle school teachers as well.8

Founding of Trinity College at No. 7 Mount Sophia. Courtesy of Trinity Theological College.

Founding of Trinity College at No. 7 Mount Sophia. Courtesy of Trinity Theological College.Correspondence between the college’s Principal Theodore Runyan and the Conference of British Missionary Societies in London reveal that its poor finances in its early years necessitated a search for aid from both American and British mission societies, which had surplus resources from China. Accepting these funds meant that the college’s direction and objectives would be diluted by the various agendas of these organisations, depending on their definition of what Christian higher education entailed.9

In 1952, local educational leaders of the Methodist Board of Education, Ho Seng Ong and Ralph Kesselring, made a serious proposal to inaugurate a Christian University College in Malaya, which would see a College of Arts within Trinity College as the possible locus to expand educational offerings for Chinese-educated students with limited tertiary options.10 These records (available at the National Archives of Singapore) – of a proposal which ultimately did not come to pass – reflect the ways in which Trinity College was at the outset implicated in much broader debates about access to higher education locally, beyond the scope of clergy-training.

That same year, the American Nanking Theological Seminary’s Board of Founders voted in favour of Trinity College’s expansion and administration. The board was founded in New York in the 1920s to administer the multimillion-dollar estate of the Swope-Wendel Fund that was aimed at supporting theological education in China. China’s changing political context of 1949 resulted in amendments to its original charter, and it sought recommendations for new expenditure elsewhere. The arrival of the board’s representatives, C. Stanley Smith and S.R. Anderson, in Singapore in 1952 were part of a broader push to expend the board’s funds in Southeast Asia as it related to the training of Chinese for Christian ministry.

The board’s vote of affirmation resulted in Smith’s relocation to Singapore as the newly appointed principal of Trinity College, while the steady influx of personnel and financial support reshaped the institution’s direction. For comparison, the reluctant one-time grant of $4,000 from the British Christian Universities Board for the salary of one professor (Frank Balachin of the London Missionary Society) was completely eclipsed by the Nanking Theological Seminary Board of Founders’ $50,000 capital grant for the renovation of the college’s Chinese Department (No. 6 Sophia Road), as well as continued support for student scholarships, faculty aid and more.11

C. Stanley Smith presenting a graduation diploma to T.C. Nga (left). She was the sole recipient of the diploma in kindergarten science at Trinity College in 1954, as Trinity’s identity as a training school was phased out in favour of theological education and clergy-training. Image reproduced from “Theology Students Will Get an Extra Year,” Straits Budget, 24 June 1954, 17. (From NewspaperSG).

C. Stanley Smith presenting a graduation diploma to T.C. Nga (left). She was the sole recipient of the diploma in kindergarten science at Trinity College in 1954, as Trinity’s identity as a training school was phased out in favour of theological education and clergy-training. Image reproduced from “Theology Students Will Get an Extra Year,” Straits Budget, 24 June 1954, 17. (From NewspaperSG).Smith’s leadership and financial aid from the Nanking Theological Seminary Board of Founders saw the college undergoing significant changes. First, it was renamed Trinity Theological College, with the foremost priority of staffing the church. Second, academic programmes in non-theological subjects were phased out by 1956, while two degree tracks in theological studies (in English and Chinese) were offered. Third, the college’s faculty was bolstered by an influx of veteran former China missionaries, such as John Fleming and Olin Stockwell. The students of such missionaries who were educated in pre-1949 China, like Anna Ling (graduate of Nanking Theological Seminary) and Enid Liu (Liu Bao-Ying, graduate of Ginling Women’s College in Nanjing), also subsequently joined Trinity’s faculty.

Trinity Theological College’s rapid development to becoming the pre-eminent theological seminary in Southeast Asia was notable. However, a renewed focus on clergy training and theological education foreclosed participation on contemporaneous debates surrounding the question of secular higher education in the colony, particularly, the rapid development of the University of Malaya as the only degree-granting institution in Singapore. A decade later, a senior member of Trinity’s staff would lament the total lack of contact between the college and the parallel worlds of (secular) higher education in Singapore, to an extent that the theological college was like “living in a ghetto” intellectually, which was most undesirable.12

William P. Fenn, the University of Malaya’s Students Christian Centre and Christians on University Campuses

The case of William P. Fenn and the United Board for Christian Colleges in China’s (United Board) expansion of its China missions into Singapore and elsewhere in Asia represents a variation on the same theme – of competing visions of how missionaries could contribute to local educational interests. The crucial difference, however, lay in the educational emphasis of these two New York-based mission boards, which defined their missions differently. Where the Nanking Theological Seminary’s Board of Founders aimed explicitly to train ministers and church workers, the United Board’s charter adopted a much more expansive definition of missions – “for any purpose contributing to Christian higher education… or for educational assistance to Chinese and other Far Eastern students”.13

In fact, Fenn’s first trip to Malaya was not as a missionary, but as an educational consultant to the government of the Federation of Malaya. As he noted in correspondences with missionaries in London concerned about opportunities for mission work among the Chinese in Malaya, Fenn was “sorely tempted” to advise the government on the need for expanded Chinese higher education, but it was beyond the purview of his assigned work.14

One of the immediate products of Fenn’s brief sojourn in Singapore and Malaya, is the oft-forgotten Students Christian Centre at the University of Malaya’s Bukit Timah Campus. For Fenn, an expansive vision of Christian missions was best enacted through spaces of community building, residential living and educational exchange not confined to university curriculum or church walls. On 6 May 1952, the United Board provided an initial appropriation of US$50,000 to be administered by the Malayan Christian Council (MCC) and university authorities. Articulated to Vice-Chancellor Sydney Caine in an initial memorandum:

“Residence would not be confined to students from Christian homes, and it was not a Christian hostel in any narrow sectarian or denominational sense, but it would aim to be a centre where the Christian faith would be upheld, discussed, presented in a way suitable to a university environment, with due consideration of the fact that the University exists or will exist in a Muslim state.”15

In addition, Fenn proposed to leverage the intellectual resources of the Christian faculty to create a non-credit educational centre where residents and students could “share in the challenges of our time and the cultural riches of east and west”.16

In 1954, the Students Christian Centre was approved by the University Council to provide a meeting place for Christians and other students, along with hostel accommodations for women. Two bungalow properties close to the university (9–11 Adam Road) were purchased with the United Board’s funds by the MCC with the intention to fully participate in university life. Staffers at the institute included Australian educator Jean Waller, assistant librarian at the University of Malaya and representative of the Student Christian Movement (SCM), and later, Fred Karat, a missionary professor from Madras Christian College also associated with the SCM. Khoo Oon Teik, a distinguished graduate and tutor at the medical school, was appointed as coordinator with local churches. At least some members of the student body of the university recalled the Students Christian Centre as “university chaplains”, reflecting their officially sanctioned presence within the university.17

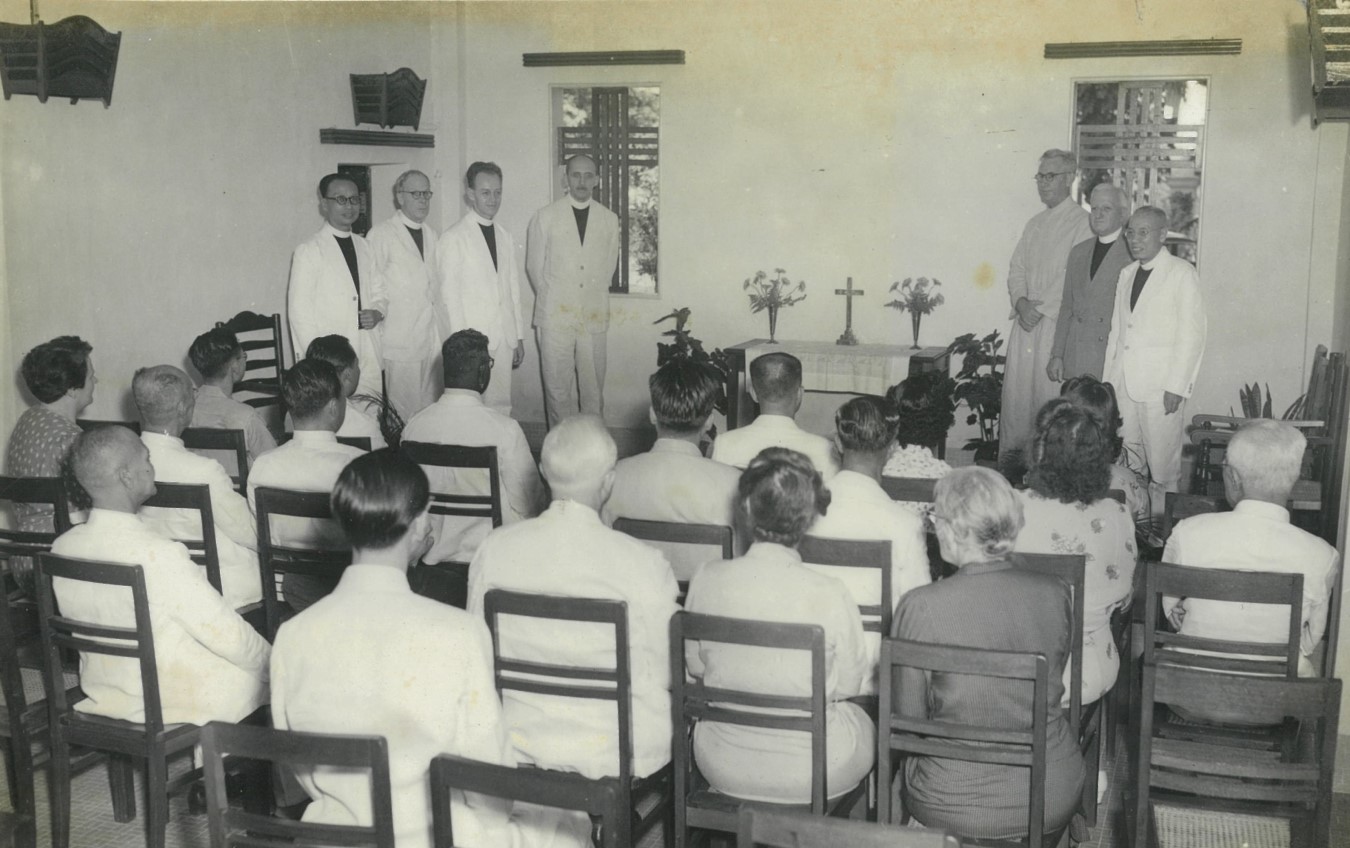

Between 1954 and 1958, 9 Adam Road was used as a community centre and 11 Adam Road as a hostel for 12 female students. As noted in a 1955 publicity brochure, the Students Christian Centre (referred to now as a University Christian Centre) was envisaged as a space where students were welcome to share in the programme of Christian fellowship, study and worship. Although not officially part of the university, its proximity to the University of Malaya and close participation of the university’s faculty, made a deeper engagement with the university possible. This close relationship was exemplified by the centre’s dedication ceremony, which was hosted by Anglican Bishop of Singapore Henry Baines and where Vice-Chancellor Sydney Caine gave the opening address to students of the university’s SCM.18 Two faculty members, T.H. Silcock and T.A. Lloyd Davies, Professor of Economics and Professor of Social Medicine and Public Health respectively, were appointed to the board.

Dedication of the University of Malaya’s Students Christian Centre. Present are the Rev Hobart Amstutz, Chair of the Board, and Sydney Caine, Vice-Chancellor of the university. Source: The Straits Times, 25 February 1955. © SPH Media Limited. Permission required for reproduction.

Dedication of the University of Malaya’s Students Christian Centre. Present are the Rev Hobart Amstutz, Chair of the Board, and Sydney Caine, Vice-Chancellor of the university. Source: The Straits Times, 25 February 1955. © SPH Media Limited. Permission required for reproduction.By all accounts, the Students Christian Centre at 9–11 Adam Road served a broad range of Protestant, Catholic, and non-Christian or non-religious undergraduates between 1954 and 1959. Its activities included social events, book discussions and talks attended mostly by members of the ecumenical Student Christian Movement. However, very little has been written about the centre, simply because its ambitious initial hopes and aspirations to be a hub of Christian discourse for students proved to be short-lived. The availability of alternative halls of residence at the university, the relative disinterest of local churches and university administration, and an untimely disintegration of the building’s roof due to termite infestation led to its premature sale and closure in 1958.

Christian activities on the university campus, however, continued to flourish in the centre’s absence via the Varsity Christian Fellowship (VCF) and Graduate Christian Fellowship.19 Founded in 1952 by conservative evangelical students under the mentorship of CIM missionary Paul Contento, they rejected the Students Christian Centre’s approach to ecumenical and interfaith relations. Instead, they stressed a more evangelical approach to proselytising Christianity among university students. Indeed, it is worth contrasting Fenn’s cautious approach when corresponding with Vice-Chancellor Sydney Caine, with that of Paul Contento’s. An avowed anticommunist who railed against the liberal ecumenism of the MCC, Trinity College and the SCM, Contento – a self-proclaimed “maverick missionary on Asian campuses” – was, in fact, biding his time as a lecturer of English at Nanyang University, where all of his students were Chinese and there was no anxiety of Muslim reprisal to his aggressive evangelism.20

Contento’s personal acquaintance with Nanyang’s Dean of Arts Chang Tien-Tse, and his personal relationships with local Chinese evangelicals (through CIM and the Graduate Christian Fellowship), provided him an extensive network through which to conduct this evangelistic work, which resulted in the strengthening of the VCF among Christian students on the university campuses.

The triumph of Contento’s alternative vision for more evangelically oriented Christian missions among university students can be seen in the repurchase of the property at 9–11 Adam Road by the CIM-supported Singapore Bible College (SBC) in 1958, where Contento also served as a part-time faculty member. Founded in 1952 by local Chinese-speaking Churches organised around a Chinese Inter-Church Union, the SBC supported missionaries from China – such as the CIM and Chinese Native Evangelicals Crusade (CNEC) – who rejected the liberal ecumenism of the mainline denominational churches which sponsored Trinity Theological College. They, too, were expanding rapidly and seeking a permanent site, and purchased the properties of 9–11 Adam Road, expanding to 13 and 15 Adam Road as well, to meet the rising demand for Bible teachers and clergy in the Chinese churches.21

With this change of hands, any connection with the secular university across the road was completely erased. Rather, the Bible College’s aims to produce lay-evangelists, missionaries and pastors willing to go to the needy and “unreached areas” of Asia to preach the gospel resonated much more with local churches, of which over 39 (mainly Chinese-speaking churches) supported the SBC.22

As with the case of Trinity Theological College, these transformations by the middle of the decade both expanded and narrowed the range of educational possibilities offered at 9–11 Adam Road. The initial vision for the Christian Student Centre targeting an Anglophone elite at the University of Malaya appealed to few. Comparatively, the straightforwardly evangelical commitments of the SBC gained widespread support among local churches, especially the Chinese-language congregations organised around the Chinese Inter-Church Union, which were forthcoming with financial support.

Yet, despite strong support from local Chinese churches, claims to localisation were tempered by the lack of attempts to articulate a contextual theology commensurate with decolonisation; the SBC’s faculty and curriculum offerings remained increasingly wedded to the worlds of American evangelicalism/fundamentalism, as evidenced by the global Chinese evangelical networks within which they participated.23 In this regard, the SBC emerged as one node within an interconnected Chinese evangelical world – across Hong Kong, Taiwan and especially the United States – while the gap between the secular university across the road was simply insurmountable.

Efforts to revive the Christian Student Centre by repurchasing another property at 14 Dalvey Estate proved unsuccessful in supporting the Student Christian Movement’s ecumenical Christian activities at the University of Malaya. As its chaplain, Reverend Dennis C. Dutton, a Trinity Theological College graduate who pursued doctoral training in the U.S., later wrote in 1967, the centre was no longer close enough to campus to attract students, and on weekends students preferred other forms of secular entertainment in town. As the University of Singapore would not permit a Christian Centre inside the campus, it was up to the students – now most of them involved with the evangelical Inter Varsity Fellowship – to organise themselves, and they increasingly did so independent of the centre.24

Today, it is not uncommon to hear Christians in Singapore claim that Singapore’s churches benefited from the missionary exodus following the 1949 Chinese revolution, which pushed mission boards and resources out of China and into the Chinese diaspora. Works of local church history like Bobby Sng’s In His Good Time, describe the missionary mass migration from China to Singapore as benefiting a new generation of churches by staffing their leadership and providing financial support at a crucial time.25

Indeed, institutions founded in the early 1950s – such as Trinity Theological College and Singapore Bible College – still remain central in cultivating Protestant leadership in Singapore today. While their achievements are notable, it is also worth considering what other possibilities for Christian engagement with secular higher education and learning more broadly were foreclosed in the same period – results of the anti-communist Emergency, the shape of decolonisation, agendas of foreign mission boards, thus delimiting what kinds of mission work were possible.

Revisiting the sojourns of these two missionaries to Singapore and their separate trajectories provides a glimpse into lesser-known histories of well-known institutions in Singapore today. They give context to the diverse forms of educational activism amid Singapore’s decolonisation of the 1950s, while offering alternative examples of Christian missions and community engagement in the present.

Joshua Tan is a historian of modern China and the Chinese diaspora, with an interest in the religious and educational politics in Cold War Asia. He is currently a postdoctoral fellow in the Department of History at the National University of Singapore and is working on a book about American-Asian educational partnerships during the Cold War.

Joshua Tan is a historian of modern China and the Chinese diaspora, with an interest in the religious and educational politics in Cold War Asia. He is currently a postdoctoral fellow in the Department of History at the National University of Singapore and is working on a book about American-Asian educational partnerships during the Cold War.Notes

-

A broader discussion is drawn from Joshua Tan’s PhD dissertation. See Joshua Tan Hong Yi, “Schooling Free Asia: Diasporic Chinese and Educational Activism in the Transpacific Cold War” (PhD diss., University of California Santa Cruz, 2024), https://escholarship.org/uc/item/4np3k5fb. ↩

-

Creighton Lacy, “The Missionary Exodus from China,” Pacific Affairs 28, no. 4 (December 1955): 301–314. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website) ↩

-

Lee Kam Hing, “A Neglected Story: Christian Missionaries, Chinese New Villagers, and Communists in the Battle for the ‘Hearts and Minds’ in Malaya, 1948–1960,” Modern Asian Studies 47, no. 6 (November 2013): 1977–2006. See also, Clemens Six, Secularism, Decolonization and the Cold War in South and Southeast Asia (New York: Routledge, 2018). (From National Library, Singapore, call no. 201.72095 SIX) ↩

-

Lee, “A Neglected Story,” 1977–2006. ↩

-

For the list of inaugural professors at Nanyang University, including a number of missionaries in the Department of Foreign Languages, see: Nanyang da xue chuang xiao shi zhou nian ji nian te kan 1966 南洋大学创校十周年纪念特刊1966 [Nanyang University tenth anniversary souvenir 1966] (Xinjiapo 新加坡: [Nanyang da xue] [南洋大学], 1966) (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RCLOS 378.5951 NAN). See also Paul Contento, A Maverick Missionary on Asian Campuses: Story of the Founding of the Iner-Varsity Christian Student Movement in China, Singapore and Vietnam by Paul and Maida Contento (Shangkuan Press, 1993) for how one missionary specifically conducted his missionary work on Asian campuses. ↩

-

At the Crossroads, 150–54. The first graduating cohort of four students in 1951 saw only two studying for the licentiate in theology, while two others studied Kindergarten Sciences and Home Economics (Wong Shuk-Moy and Ang Jiak-Woon respectively); a balance which was increasingly skewed in favor of the training in secular subjects or preparation to being middle school teachers. In this regard, continuing the earlier work of the Methodist extension and training school. ↩

-

S.R. Anderson and C. Stanley Smith, The Anderson-Smith Report on Theological Education in Southeast Asia: Especially As It Relates to the Training of Chinese for the Christian Ministry: The Report of a Survey Commission, 1951–1952 (New York: Board of Founders, Nanking Theological Seminary, 1952), 25, Internet Archive, https://archive.org/details/andersonsmithrep0000ande/page/n3/mode/2up. ↩

-

Trinity Theological College (Singapore), Progress Report from Trinity Theological College, Singapore (Singapore: Trinity Theological College, 1966). (From PublicationSG) ↩

-

Conference of British Missionary Societies, “Conference of British Missionary Societies: Malaya Christian Council [a] Correspondence, Rev. J. Fleming, 1951–1958,” Noel Slater to Rev Stanley Dixon, 15 October 1951, private records. (From National Archives of Singapore, microfilm no. NAF 00020 /1); Conference of British Missionary Societies, “Conference of British Missionary Societies: Malaya Christian Council [a] Correspondence, Rev. J. Fleming, 1951–1958,” T. Runyan to the Rev. Stanley Dixon, 9 February, 1952, private records. (From National Archives of Singapore, microfilm no. NAF 00020 /1). F.S. Drake, missionary Sinologist of the Baptist Missions Board eventually took up the position of Chair in Chinese at Hong Kong University. ↩

-

Conference of British Missionary Societies, “Conference of British Missionary Societies: Malaya Christian Council [a] Correspondence, Rev. J. Fleming, 1951–1958.” ↩

-

At The Crossroads, 154. Subsequently, what inaugural President Runyan termed an “affiliated relationship” with the Nanking Board helped Trinity College realise the possibilities of its strategic situation in Southeast Asia. ↩

-

Thio Chan Bee, “The People Whom We Met and General Impressions,” in Collected Materials, Malaya/Singapore, 1966-1967. Yale Divinity Library, Records of the United Board for Christian Higher Education in Asia, New Haven, CT. (RG 11A, Box 65A Folder 869.) ↩

-

William P. Fenn, Ever New Horizons: The Story of the United Board for Christian Higher Education in Asia (New York: Mennonite Press, 1980), 68. ↩

-

The National Archives (United Kingdom), “Colonial Office - Federated Malay States: Original Correspondence: Education Policy. Fenn Wu Report,” 1 January 1950–31 December 1951, private records. (From National Archives of Singapore, accession no. CO 717/191/52336/3; microfilm NAB 1064) ↩

-

William Fleming (Malaya Christian Council) to Sidney Caine (Vice-Chancellor of the University of Malaya), 25 September 1952, see University of Malaya (UM), “Christian Hostel Centre From Malayan Christian Council,” (1952–1957). (From National Archives of Singapore, reference no. U.M.154/52; microfilm no. AM 052) ↩

-

University of Malaya (UM), “Christian Hostel Centre From Malayan Christian Council.” ↩

-

Interview with Professor Lee Soo Ann, 25 September 2024. ↩

-

“Christian Centre,” Straits Times, 11 February 1955, 4. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Bobby E.K. Sng, In His Good Time: The Story of the Church in Singapore, 1819–1992, 3rd. ed. (Singapore: Bible Society of Singapore/ Graduate Christian Fellowship, 2003), 260. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 280.4095957 SNG). Sng briefly discusses the split between liberal protestantism and evangelicalism (the adversarial relationship between the Student Christian Movement and Varsity Christian Fellowship), which was confirmed by 1952. As Sng notes, the SCM was active at Trinity Theological College, but interestingly not at Nanyang University, where the Chrisitan students with backgrounds in the Chinese-language churches were all evangelicals. ↩

-

Contento, A Maverick Missionary on Asian Campuses. According to CIM missionary Paul Contento’s memoirs, Mrs Elisabeth Contento was then teaching at China Northwest University at Xi’an; Dean of Arts Chang Tien-Tse, who arrived in SIngapore in 1955, met with Mrs Contento and invited them both to Nanyang University to teach English. ↩

-

嘉声. Jia Sheng (Xin jia po shen xue yuan bi ye te kan) (Singapore: The Singapore Bible College, 1964). (From PublicationSG). Notably, the chief architect of the SBC was not a Western missionary, but the itinerant Chinese evangelist Calvin Chao, whose repudiation of missionary liberalism was well-known in Chrisitan circles. Chao, who had arrived in Singapore in 1951, had also raised money from American sources – an undisclosed sum from the Crowell Trust for Evangelical Education, founded by the Quaker Oats conglomerate – to fund the Singapore Theological Seminary (later renamed Singapore Bible College). ↩

-

Comparatively, only two congregations – the Straits Chinese Presbyterian churches of Orchard Road and Prinsep Street – were actively supporting the short-lived student centre, whose vaguely defined vision of interreligious dialogue and ecumenical fellowship did not gain sufficient traction. ↩

-

For example, the libraries at Singapore Bible College (still located at 9–15 Adam Road) still retain an extensive collection of what Chinese evangelical publications published and circulated from Hong Kong, Taiwan and the United States. These include: Shengming Yuekan (Life Monthly) published by China Evangelical Fellowship in Hong Kong, Dengta (Lighthouse) published in Hong Kong by the China Inland Mission / Overseas Missionary Fellowship, Zhongxin Yuekan (China Christian Monthly), published by the Chinese Christian Mission in Petaluma, California. For an elaboration of Chinese evangelical networks in the mid-20th century, see: Joshua Dao-Wei Sim, “Bringing Chinese Christianity to Southeast Asia: Constructing Transnational Chinese Evangelicalism across China and Southeast Asia, 1930s to 1960s,” religions 13, no. 9 (2022): 773, https://www.mdpi.com/2077-1444/13/9/773. ↩

-

Thio, “The People Whom We Met and General Impressions.” ↩

-

Sng, In His Good Time, 210. ↩