The House of Cheang

The Cheangs were once one of Singapore’s most illustrious Baba-Nonya families.

By Professor Walter Woon

On Pasir Panjang Road stands one of the last grand houses that used to line the millionaires’ enclave where rich Baba families built their seaside mansions. Once named “Palm Beach”, the property is a reminder of the opulence that once characterised the prominent Baba-Nonya (or Peranakan) families of Singapore.1 The house was built by Cheang Jim Chuan, a scion of the prominent Cheang family in colonial Singapore. Cheang Jim Chuan’s father was the most famous of the Cheangs – Cheang Hong Lim, after whom Hong Lim Park is named. At one time, a substantial part of Chinatown was owned by Cheang Hong Lim and his relatives.

The house at 233 Pasir Panjang Road, built circa 1937 by Cheang Jim Chuan. It was originally numbered 113 and named Palm Beach. Courtesy of Professor Walter Woon.

The house at 233 Pasir Panjang Road, built circa 1937 by Cheang Jim Chuan. It was originally numbered 113 and named Palm Beach. Courtesy of Professor Walter Woon.Cheang Sam Teo and the Opium Farm

According to family tradition, Cheang Hong Lim’s father, Cheang Sam Teo (d. 1862), left Teang Thye Village in Fukien Province, China, around 1820. He may have first gone to Batavia (now Jakarta) in the Netherlands East Indies, where migrants from Teang Thye had established a temple.2 Cheang Sam Teo, together with Tay Han Long (father of Tay Ho Swee), had a business at Telok Ayer Street under the chop Teang Wat.3 Cheang Sam Teo made his fortune trading in the Nanyang and, by the 1840s, had become the Opium Farmer in Singapore.4

At the time, the sale of opium was both legal in the Straits Settlements and encouraged by the British East India Company. The right to distribute opium within a territory was auctioned to the highest bidder. This was the so-called opium farm. The opium farmer had an exclusive licence to distribute opium in return for a fee paid to the government. There were other types of revenue farms (such as gambier, spirits, toddy and pork), but the fees from the opium farm made up the bulk of the income of the Straits government.5

Although the opium farm was ostensibly awarded to a named individual, in reality he represented a syndicate, or kongsi.6 No doubt the arrangements among the members of the syndicate would have been governed by Chinese principles, but the commercial law of the Straits Settlements was entirely English.7 In legal terms, this would have been a partnership. The farm would have had to have been held by a named individual as the concept of a company with a legal personality8 was not established until the latter part of the 19th century.

The opium farm was mostly controlled by syndicates of merchants from a particular Chinese province. The different Chinese dialect groups formed self-help societies (such as clan associations) to aid migrants from the same province. These self-help societies, contrary to popular belief today, were neither illegal nor criminal.9

There was stiff competition and constant commercial rivalry between syndicates for the opium farm. When one syndicate obtained the farm, their rivals would try to break their monopoly by smuggling opium into the territory. This was not a crime as we know it today. Back then, there was no developed means of enforcing the monopoly against outsiders through a lawsuit for damages as one would do today. Instead, the opium farmer protected the syndicate’s rights through private prosecutions; fines were levied which were shared between the prosecutor and the government. This was the way that private individuals obtained redress in contemporary England. The syndicates also employed revenue officers known as chinteng10 to police their monopolies; these men were often from the same community as the leading members of the kongsi and did not always deal with infringements gently.

In Singapore, there was hostility between the Hokkiens and Teochews, which resulted in riots on several occasions. Later in the 19th century, colonial authorities designated some of the more violent elements of the clan and provincial associations as criminal “secret societies”.11 However, self-help communities remained an essential part of Chinese commercial life in the Straits Settlements, despite the abuses perpetrated by some of their members.

In the 1840s, Cheang Sam Teo and some other merchants formed a syndicate to acquire the opium farm and spirit farm (the two often were held by the same merchants). At the time of his death in 1862, Cheang Sam Teo was the spirit farmer in Singapore. His son Cheang Hong Lim became the spirit farmer the next year, presumably in partnership with others since legally his “share” in the syndicate could not be inherited. He was barely 21 at the time. Eventually, Cheang Hong Lim became a leading member of the Great Syndicate that held the opium and spirit farms for Singapore, Johore, Malacca and Rhio from 1871 to 1879.12

Cheang Hong Lim

Cheang Hong Lim (1841–93) was one of the great philanthropists of Singapore and is commemorated by two streets in Singapore: Cheang Hong Lim Place and Cheang Wan Seng Place (Cheang Hong Lim’s business was conducted under the name Chop Wan Seng).13

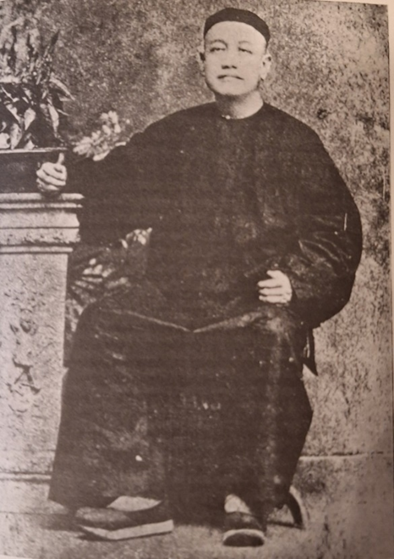

This photo of Cheang Hong Lim adorned the walls in the homes of many of his descendants, even two generations removed. Courtesy of Professor Walter Woon.

This photo of Cheang Hong Lim adorned the walls in the homes of many of his descendants, even two generations removed. Courtesy of Professor Walter Woon.Besides being the farmer for opium and spirits, he also owned extensive tracts of land in Chinatown and was a “large house-property owner” particularly along Havelock Road. In 1876, he contributed funds to convert the empty land in front of the then Police Courts into a public garden.14 This still bears his name today as Hong Lim Park. He also owned Hong Lim Market and would advance money liberally to stallholders. According to Song Ong Siang in 100 Years’ History of the Chinese in Singapore, “[Cheang Hong Lim] was a man who trusted too readily to other people’s honesty”. When he died, it was discovered that the enormous sum of over $400,000 had been lent to “friends” and could not be recovered.15

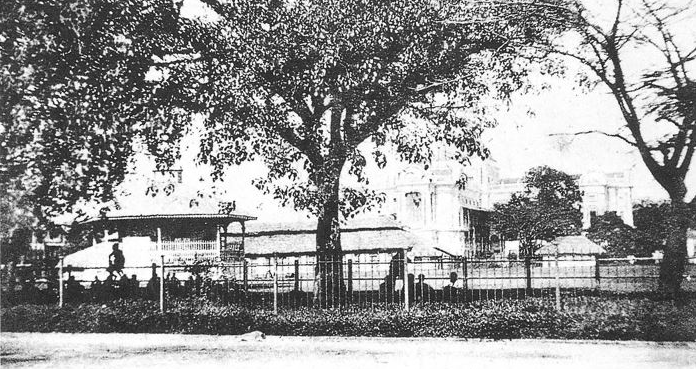

Hong Lim Green was later renamed as Hong Lim Park, c. 1900. Image reproduced from Singapore River Planning Area: Planning Report 1994 (Singapore: Urban Redevelopment Authority, 1994), 7. (From National Library Singapore, call no.: RSING 711.4095957 SIN).

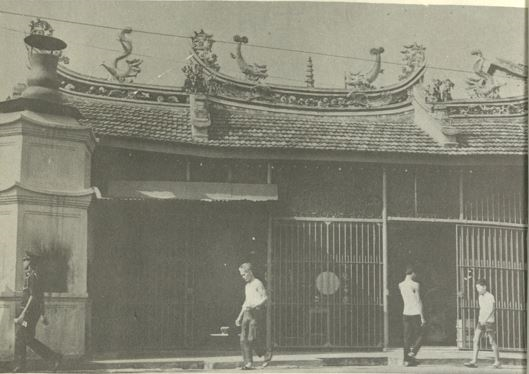

Hong Lim Green was later renamed as Hong Lim Park, c. 1900. Image reproduced from Singapore River Planning Area: Planning Report 1994 (Singapore: Urban Redevelopment Authority, 1994), 7. (From National Library Singapore, call no.: RSING 711.4095957 SIN). Another of Cheang Hong Lim’s contributions was Giok Hong Tian temple (玉皇殿) located near the junction of Havelock and Zion roads. The temple is dedicated to the Jade Emperor (玉皇上帝, Yu Huang Shang Ti) and established in 1887. Image reproduced from 陈汉荣 [Chen Hanrong]. 新加坡古迹. [Xin jia po gu ji]. (Singapore, 1978), 96. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 959.57 CYY -[HIS]).

Another of Cheang Hong Lim’s contributions was Giok Hong Tian temple (玉皇殿) located near the junction of Havelock and Zion roads. The temple is dedicated to the Jade Emperor (玉皇上帝, Yu Huang Shang Ti) and established in 1887. Image reproduced from 陈汉荣 [Chen Hanrong]. 新加坡古迹. [Xin jia po gu ji]. (Singapore, 1978), 96. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 959.57 CYY -[HIS]).Among his many public contributions to Singapore and the Straits Settlements was his donation to the Convent of the Holy Infant Jesus (today’s CHIJMES) for the construction of the long building on its southern boundary.16 He also supported the charitable school in Penang, the Dutch elementary school and the Portuguese kindergarten. Together with his eldest son, Cheang Jim Hean, he established Yangzheng Academy, which taught Chinese and Western studies with six Chinese and six English teachers.17

His generosity extended beyond Singapore. He regularly contributed to flood and disaster relief in China, India and Egypt, raising large sums for the purpose. His philanthropy included hospitals, orphanages, homeless shelters, shelters for widows and community cemeteries.18

Despite being in Singapore, Cheang Hong Lim supported China’s various war efforts. In 1869, he bought weapons and helped to transport provisions for troops defending Fukien against the French. In 1884, he provided intelligence on French military movements against China. For his efforts in supporting the coastal defense in Fukien, the Governor-General of the Fukien Province conferred upon him the title of Circuit Intendant.19 Ironically, on the recommendation of Bishop Edouard Gasnier of Malacca-Singapore, he also received a medal for his acts of charity in Saigon (Vietnam) from the French government, who was presumably unaware of his support of China against French aggression.20

Chinese statesman Grand Mentor Li Hongzhang (1823–1901) sent a request to the Chinese Imperial Court in 1881 for the words “He takes delight in good deeds and loves to give aid to others” to be inscribed on a memorial arch in Cheang Hong Lim’s ancestral village of Teang Thye (unfortunately, this arch no longer exists). In recognition of his contributions, Cheang Hong Lim was accorded Second Rank status and honours from the Ministry of Rites and was specially promoted to become a Salt Commissioner.21

Cheang Hong Lim was appointed a Justice of the Peace in Singapore in 1873.22 Towards the end of his life, in 1892, he was recognised by colonial authorities (and succeeding Tan Kim Cheng) as the “head of the Hokien (sic) community, to whom disputes and misunderstandings among members of that community may properly be referred”.23 There was a grand celebration by the community on 1 October 1892 accompanied by the band of St Joseph’s Institution.24 He was also appointed to the Chinese Advisory Board, Singapore, in September 1892.25

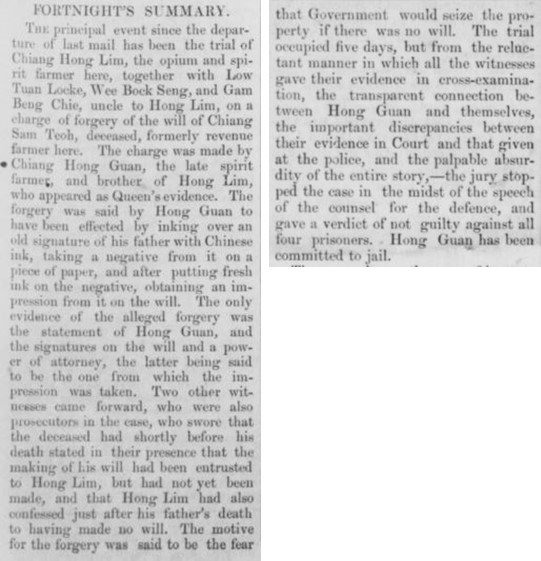

However, great wealth attracts great envy. In 1872, Cheang Hong Lim was prosecuted by his younger brother, Cheang Hong Guan, for the alleged forgery of his father’s will.26 Cheang Hong Guan won the bid for the Singapore, Johore and Malacca opium and spirit farms from 1870 to 1871, but had made a hash of it and lost a fortune.27 Cheang Hong Lim and other merchants formed the Great Syndicate and took over the Farms from 1871–79.28 The prosecution brought by Cheang Hong Guan against his brother was presumably a form of retaliation.

The trial lasted five days. Cheang Hong Guan was the principal witness. The case collapsed ignominiously. Before the Defence Counsel had finished his speech, the jury stopped the trial because of the patent absurdity of the charge and the contradictions in the evidence of the witnesses. The Chief Justice of the Straits Settlements declared to Cheang Hong Lim that “you leave the Court without a stain on your honour”.29 Cheang Hong Guan, on the other hand, was jailed for his part in this farce.30

Newspaper excerpt of Cheang Hong Lim’s trial. He had been accused by his younger brother for forging their father’s will. He was acquitted and his brother jailed. Source: “[Fortnight’s Summary],” Straits Times, 27 April 1872 © SPH Media Limited. Permission required for reproduction.

Newspaper excerpt of Cheang Hong Lim’s trial. He had been accused by his younger brother for forging their father’s will. He was acquitted and his brother jailed. Source: “[Fortnight’s Summary],” Straits Times, 27 April 1872 © SPH Media Limited. Permission required for reproduction.After 1879, the farm changed hands again. The new opium farmer alleged that the losers were smuggling opium to undermine their monopoly. Cheang Hong Lim was accused of being part of this so-called “Opium Conspiracy”. In 1883, he was removed as a Justice of the Peace due to these allegations.31 An article was published in the Straits Intelligence on 24 February 1883 giving vent to the allegations of conspiracy. Cheang Hong Lim responded in a very Singaporean way – he sued for defamation. Technically, he instituted a private prosecution for criminal defamation to be heard by the Police Magistrate.32 There is no record of the result, but the Straits Intelligence disappears after that. Cheang Hong Lim was vindicated and reinstated as a Justice of the Peace in 1887.33

Cheang Hong Lim died on 11 February 1893, leaving a considerable fortune both in the Straits Settlements as well as China. The executors of his will (which is now part of the National Library’s collection) were his eldest daughter, Cheang Cheow Lian Neo, and his two eldest sons, Cheang Jim Hean and Cheang Jim Chuan, who were minors at the time of his death. Unsurprisingly, there was a controversy about the administration of the estate – Lim Kwee Eng, his agent and his daughter’s (Cheang Cheow Lian Neo) husband, had presumably wanted to control everything. Litigation followed in 1896. The Court ordered Dr Lim Boon Keng (an eminent figure in the Straits Chinese community, who had also worked for Cheang Hong Lim) to prepare a scheme for the division of Cheang Hong Lim’s estate. The scheme was duly approved by Chief Justice Cox on 4 February 1901.34 Unfortunately, it was not wholly carried out and to this day, there remain slivers of land in Singapore still registered in the name of the Estate of Cheang Hong Lim.

Cheang Hong Lim’s ancestral tablet, the names on the left are of his children, c. 1978. Ronni Pinsler Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Cheang Hong Lim’s ancestral tablet, the names on the left are of his children, c. 1978. Ronni Pinsler Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.End of an Era

What then became of the House of Cheang? It is said that wealth only lasts three generations and the Cheangs were no exception. The first was Cheang Sam Teo. The second was his son Cheang Hong Lim. The third was Hong Lim’s second son Cheang Jim Chuan (Cheang Jim Hean, the eldest, died in 1901).35

Photo of Cheang Hong Lim’s second son, Cheang Jim Chuan, taken in 1929 at his former house, named Riviera, at 112 Pasir Panjang Road. Courtesy of Professor Walter Woon.

Photo of Cheang Hong Lim’s second son, Cheang Jim Chuan, taken in 1929 at his former house, named Riviera, at 112 Pasir Panjang Road. Courtesy of Professor Walter Woon.Very little is recorded of Cheang Jim Chuan. He was known principally as the son of Cheang Hong Lim. His income was derived from landed property.36 At the beginning of the 20th century, he lived at 10 Mohamad Sultan Road before moving to 6 Nassim Road. In the 1920s, the family moved again, this time to a grand house named Riviera at 112 Pasir Panjang Road owned by his wife Chan Kim Hong Neo.37

Wedding procession of Cheang Seok Cheng Neo (Cheang Jim Chuan’s daughter) and Woon Chow Tat leaving Riviera 112 Pasir Panjang Road, 27 September 1930. Riviera was acquired by the government and likely demolished in the 1970s. A road now runs through it. Courtesy of Professor Walter Woon.

Wedding procession of Cheang Seok Cheng Neo (Cheang Jim Chuan’s daughter) and Woon Chow Tat leaving Riviera 112 Pasir Panjang Road, 27 September 1930. Riviera was acquired by the government and likely demolished in the 1970s. A road now runs through it. Courtesy of Professor Walter Woon.Chan Kim Hong Neo died on 1 March 1934. Riviera was sold by the executors of her will, Cheang Theam Chu, Cheang Theam Kee and Cheang Seok Hean Neo (who were also her children. Her husband, Cheang Jim Chuan, had renounced his appointment as executor of her will).38 The house was purchased by Cheang Jim Chuan from the estate in April 1935 for $20,000.39

Upon Chan Kim Hong Neo’s death, the family of Cheang Jim Chuan lived temporarily at 38, 40 and 42 Cairnhill Road. These houses were bought from the Hong Kong and Shanghai Bank for $140,000 on a mortgagee’s sale of the property of Tan Kah Kee.40 In the meantime, Cheang Jim Chuan began building his new house called “Palm Beach” at 113 Pasir Panjang Road. The formal conveyance of the property from Hugh Zehnder (the family lawyer) to Cheang Theam Kee (presumably as trustee for his father Cheang Jim Chuan) was executed on 19 May 1937.41 Cheang Jim Chuan moved into Palm Beach in May or June 1937 and his sons held a birthday dinner for him there on 18 June.42

Cheang Jim Chuan did not live in Palm Beach for very long as he died on 22 May 1940. According to his will, dated 15 April 1939, his fortune was left to his two sons, four daughters, and grandchildren. Palm Beach was left to his second wife Koh Guek Chew Neo, his son Cheang Theam Kee and daughters Cheang Seok Hean Neo and Cheang Seok Chin Neo.

Following Japan’s attack on Malaya on 8 December 1941 that signalled the start of the Second World War in Singapore, the British ordered the residents of the beachfront houses in Pasir Panjang to evacuate around 12 December 1941.43 The Cheangs never returned to 113 Pasir Panjang Road. It was sold to Yap Ee Chian on 15 June 1946 and was eventually bought by the Church of Jesus Christ of the Latter Day Saints in the 1980s.

The Japanese Occupation ruined many of the old Baba-Nonya families. The Japanese extorted money from the Chinese of the Straits Settlements and stole whatever valuables they could from the grand houses of the Baba-Nonya community. Many families had to sell their properties to survive. The end of the war and the return of the King in 1945 found the Baba-Nonya community much diminished in influence and affluence. After the war, rent control (the Control of Rent Ordinance was passed in 1947) also made it impossible to live off income from property. The last tangible reminder of the House of Cheang is the big house on Pasir Panjang Road, which may soon be redeveloped into a Mormon Temple.

Professor Walter Woon is a Lee Kong Chian Visiting Professor at the Singapore Management University, Honorary Fellow at St. John’s College Cambridge University, and Emeritus Professor at the National University of Singapore.

Professor Walter Woon is a Lee Kong Chian Visiting Professor at the Singapore Management University, Honorary Fellow at St. John’s College Cambridge University, and Emeritus Professor at the National University of Singapore.Notes

-

The title deeds pertaining to this property were donated to the National Library Board by Professor Walter Woon. ↩

-

Information from a delegation of officials from Changtai District of Zhangzhou Municipality, 19 December 2024. The delegation was researching the history of people from Changtai who had emigrated to the Nanyang. Before arriving in Singapore they had visited Jakarta. ↩

-

Song Ong Siang, One Hundred Years’ History of the Chinese in Singapore (Singapore: Oxford University Press, 1984), 168-170. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 959.57 SON-[HIS]) ↩

-

Carl A Trocki, “The Rise of Singapore’s Great Opium Syndicate 1840–86,” Journal of Southeast Asian Studies 18, no. 1 (March 1987): 65 (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website). He held the Johore and Singapore Opium and Spirit Farms together with Lao Joon Teck from 1847–60. ↩

-

Trocki, “The Rise of Singapore’s Great Opium Syndicate 1840–86,” 60–62. ↩

-

Trocki, “The Rise of Singapore’s Great Opium Syndicate 1840–86,” 62. For a discussion of the nature of these business organisations see Lynn Pan, ed. The Encyclopedia of the Chinese Overseas (Singapore: Archipelago Press, 1998), 91–92. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 304.80951 ENC) ↩

-

This was eventually formalized in the Civil Law Ordinance 1878, which provided that English commercial law would apply in the Straits Settlements. The English Partnership Act 1890 remains law in Singapore till today. ↩

-

Joint stock companies as we know them today are legal entities separate from the persons who own the shares. This means that a company can hold property (e.g. a licence) in its own name. A partnership does not have a legal personality; consequently, one of the partners must be registered as licence-holder even though it is the partnership that runs the business. ↩

-

Irene Lim, Secret Societies in Singapore (Singapore: National Heritage Board, Singapore History Museum, 1999), 9–10. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 366.095957 LIM) ↩

-

Trocki, “The Rise of Singapore’s Great Opium Syndicate 1840–86,” 69. ↩

-

These criminal elements were banned by the Societies Ordinance 1889. ↩

-

Trocki, “The Rise of Singapore’s Great Opium Syndicate 1840–86,” 65. ↩

-

Tan Ban Huat, “Cheang Hong Lim – The Big Property Owner and Philanthropist,” Straits Times, 14 October 1977, 8. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Song, One Hundred Years’ History of the Chinese in Singapore, 168-170.; Tan Ban Huat, “Cheang Hong Lim – The Big Property Owner and Philanthropist.” ↩

-

Song, One Hundred Years’ History of the Chinese in Singapore, 168–70. ↩

-

Song, One Hundred Years’ History of the Chinese in Singapore, 169. ↩

-

Epitaph for Cheang Hong Lim composed by Huan Zunxian, Chinese Consul General in Singapore, in 1893. Reproduced in Kenneth Dean and Hue Guan Thyre, Chinese Epigraphy in Singapore 1819–1911 (Singapore: NUS Press, 2017), chapter 41. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 495.111 DEA) ↩

-

Dean and Hue, Chinese Epigraphy in Singapore 1819–1911, chapter 41. ↩

-

Dean and Hue, Chinese Epigraphy in Singapore 1819–1911, chapter 41. ↩

-

Song, One Hundred Years’ History of the Chinese in Singapore, 169. ↩

-

Song, One Hundred Years’ History of the Chinese in Singapore, 169. ↩

-

“Untitled,” Straits Times Overland Journal, 10 April 1873, 8. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Letter from W E Maxwell, Colonial Secretary dated 7 September 1892; reported in the Daily Advertiser, 13 September 1892 (see “Local and General,” Daily Advertiser, 13 September 1892, 3. (From NewspaperSG)). ↩

-

“Local and General,” Daily Advertiser, 1 October 1892, 3; “Summary of the Week,” Straits Times Weekly Issue, 5 October 1892, 1. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Straits Settlements, Government Gazette, 9 September 1892. ↩

-

Song, One Hundred Years’ History of the Chinese in Singapore, 167-168. “Fortnight’s Summary,” Straits Times, 27 April 1872, 1. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Trocki, “The Rise of Singapore’s Great Opium Syndicate 1840–86,” 78. ↩

-

Trocki, “The Rise of Singapore’s Great Opium Syndicate 1840–86,” 65. ↩

-

Song, One Hundred Years’ History of the Chinese in Singapore, 168. ↩

-

“Fortnight’s Summary.”; Song, One Hundred Years’ History of the Chinese in Singapore, 168. ↩

-

“Untitled,” Straits Times, 24 February 1883, 2. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Magistrate’s Court,” Straits Times, 12 March 1883, 11. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Local and General,” Straits Times Weekly Issue, 6 July 1887, 2. (From NewspaperSG); “The Jubilee,” Straits Times Weekly, 6 July 1887, 7. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Recitals in the Deed of Acknowledgement between Lim Swee Neo and Cheang Jim Chuan, 29 June 1909. ↩

-

Cheang Hong Lim’s eldest daughter, Cheang Chow Lean Neo, had married Lim Kwee Eng, Cheang Hong Lim’s manager and agent. A notice announcing his appointment was published in the newspapers on 13 October 1890. By custom, Cheang Chow Lian Neo became part of Lim Kwee Eng’s family upon her marriage; her descendants did not bear the Cheang name. ↩

-

Arnold Wright and H. A. Cartwright (Eds.), Twentieth Century Impressions of British Malaya (London: Lloyd’s Greater Britain Publishing Company Ltd, 1908), 637. (From National Library Singapore, call no. RSING 959.51033 TWE). This monumental work cost the princely sum of $150 in 1908, which was beyond the means of most people then. ↩

-

Will of Chan Kim Hong Neo dated 13 January 1933 (From NL Online). Chan Kim Hong Neo was herself wealthy, owning several properties and substantial jewellery. These properties were probably inherited from her father Chan Cheng Wah. ↩

-

Renunciation of Probate filed on 22 March 1934. Probate No 92 of 1934. ↩

-

“Property Sale,” Straits Times, 18 April 1935, 9. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Conveyance, dated 17 September 1934. ↩

-

At this point Cheang Jim Chuan returned the Cairnhill properties to the Hong Kong and Shanghai Bank. 42 Cairnhill Road was subsequently purchased by Tan Chin Tuan. The house still stands today. ↩

-

“Domestic Occurrences Announcement,” Malaya Tribune, 16 June 1937, 12. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

An application for leave by Woon Chow Tat dated 11 December 1941 listed the reason for application (somewhat blandly) as “evacuation”. (From Professor Walter Woon’s personal collection). ↩