My Childhood Memories: A Slice of Kampong Life

Kampong living reflects an idyllic bygone age, a time when life was much simpler.

(To read this in Chinese, click here.)

By Ang Seow Leng

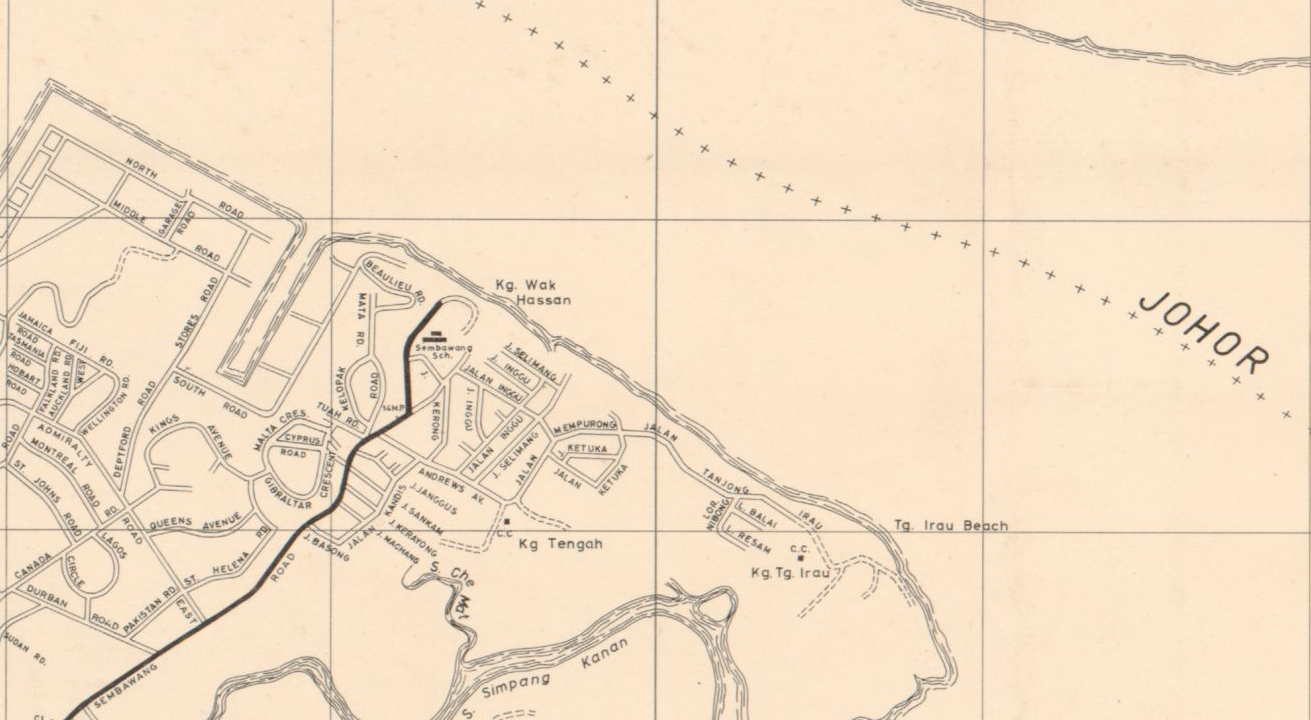

When I was a child during the late 1970s and early 1980s, my parents would take me from my maternal grandparents’ home in Hougang and bring me to my paternal grandfather’s home in Kampong Wak Hassan near Sembawang Park. I would stay there every weekend and for a short period during the Lunar New Year.

As I suffered from motion sickness, the bumpy hour-long ride often made me dizzy and nauseous. But my mood would lighten whenever our car turned into the bendy narrow Old Upper Thomson Road. The sight of black-and-white bungalows along the road flanked by lush rain trees was a sign that we were almost there.

The next scene that greeted us was the coconut trees and a myriad of fruit trees, followed by the sound of lolling waves. I would relish the gentle, briny sea breeze on my face and enjoy the sight of busy soldier crabs scavenging on the sandy shore at low tide. I spent countless leisurely weekends at my grandfather’s kampong that saw the ebb and flow of tides, along with the rhythmic chorus of insects.

A Kampong by the Sea

Before World War II, my great-grandfather left his home village in Jieyang, Guangdong, to seek a living in Nanyang (“South Seas”, 南洋; often used to refer to Southeast Asia by early Chinese migrants) when his sugar processing factory was destroyed by floods. He first settled down in Thailand. Burdened with debt and the need to feed his family, he started selling chendol (a Southeast Asian dessert). Shortly after, also before the war, he relocated to Kampong Wak Hassan, a Malay village in northern Singapore facing the Straits of Johor.

As most of the villagers were fishermen, my great-grandfather also became one and was joined by my grandfather. They worked hard to pay off the debts and saved enough to open a provision shop in the village. The shop and the adjoining house were fondly referred to by family as “Ah Gong’s house”.

Kampong Wak Hassan – with its mix of Malay, Chinese (mostly Teochew) and Indian villagers – was one of several coastal villages dotting Singapore’s northern coastline. Interestingly, there was a Teluk Jawa fishing village in Johor known as “Ang village” established during the 19th century as most of the Chinese villagers came from the same province as my grandfather and were fishermen as well.

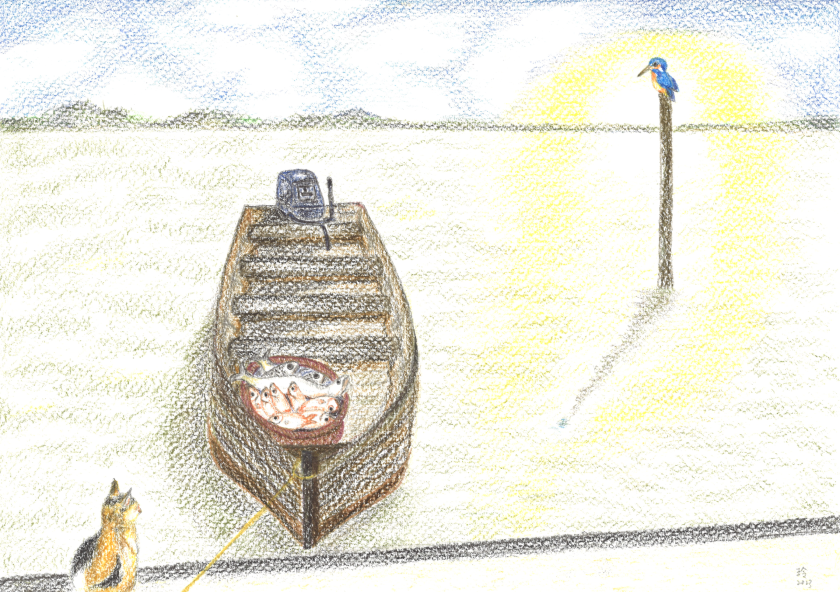

In the village, we would wake up to the loud booming voice of a Chinese fisherman from Johor. He would arrive in a motorboat filled with his catch of the day and set up a temporary spot near my grandfather’s provision shop to sell fish such as grouper and kembong (Indian mackerel). In those days, it was easy for Johor fishermen and villagers in the kampong to meet and trade, but as they grew older and with Singapore’s stricter maritime law enforcement, such interactions soon came to a halt.

In 1966, the kampong welcomed its first asphalt-paved main road, Jalan Kampong Wak Hassan, opened by Minister of State for Culture Lee Khoon Choy. During his speech, he praised the villagers as he had heard that “Kampong Wak Hassan is a model village where the Chinese, Malay and Indian villagers get along well with each other”.1 The other side lanes remained as sandy paths with potholes filled with stones or rocks of various shapes and sizes. Cyclists passing through needed to be skilful to avoid a bad fall.

At dusk when the dim streetlamps illuminated the roads, villagers turned in for the night lulled by the sound of soothing waves and the distant melody of someone strumming the guitar. During low tide evenings, Malay villagers carried kerosene lamps and waded in knee-deep seawater to catch prawns or squids under the starry skies. Back then, pollution was unheard of, and the air was fresh and clean.

Uniting People Through Food

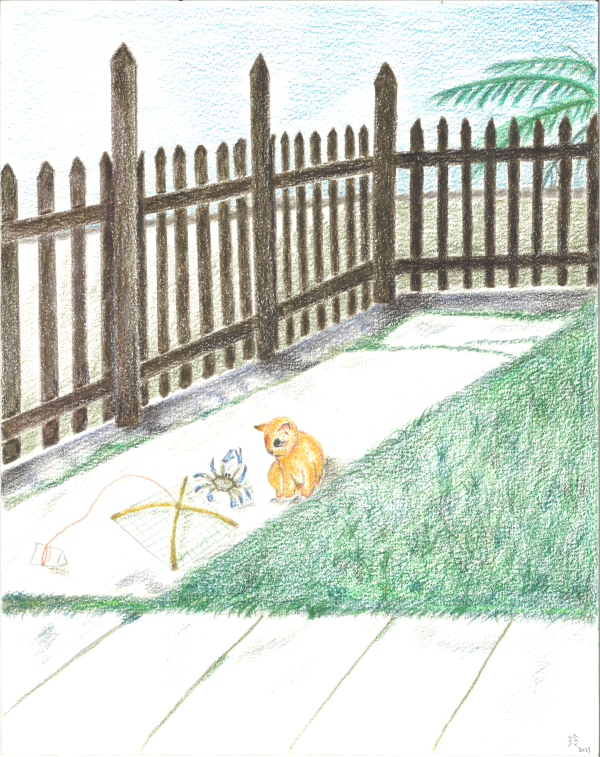

Living near the coastal region meant that there was always an abundant supply of seafood like crabs, shrimps and all sorts of fish. Children also had fun digging up cockles from the muddy shore.

While it was easy to catch seafood, villagers had to travel further afield to the Chong Pang market to buy fresh fruits and vegetables. Every household reared some chickens and ducks for eggs and meat. Occasionally, one might spy an escaped goat exploring the neighbourhood. Cats, as popular pets, were the nemesis of roaches, lizards and rats. Villagers also grew their favourite fruit trees. My family was spoilt for choice with mango, starfruit, jackfruit, chiku, rambutan, mulberry and coconut trees.

Whenever I stayed with my grandfather, I would spend a lot of time in the kitchen observing my aunts as they cooked. Once, a chicken whose neck had been partially severed, escaped from my aunt’s grip leaving behind a bloody trail on the floor. Till today, I still shudder when I recall that scene.

My grandfather passed away at the ripe old age of 103. I remember that he ate simply – just a bowl of rice porridge with steamed fish for breakfast. Lunch and dinner were also simple affairs, prepared by my fourth aunt. Similarly, my grandmother was not a fussy eater. My grandparents never talked about what they used to eat back in their hometown of Jieyang.

Chinese festivals were extremely busy periods with a hive of activity in the kitchen. The neighbours and aunties would congregate to prepare and cook delicious festive food. You won’t find large groups of people coming together to prepare food for a big event today.

During the Dragon Boat Festival (端午节) on the fifth day of the fifth lunar month – which was a big celebration back then – there would be a division of labour, with each person assigned different tasks such as frying mushrooms and dried prawns, washing glutinous rice, cleaning chestnuts, peanuts, and cutting and marinating pork. More than a hundred rice dumplings could be wrapped in a single day, and these would be lowered into two large steamers bubbling away on charcoal stoves situated at the skywell of my grandfather’s house.

As the women gathered to wrap the dumplings, younger children like me would be doing odd duties in the kitchen, enjoying each other’s company and chatter. The cooked rice dumplings were then distributed to relatives and friends.

During occasions such as Qingming and the Hungry Ghost Festival when we worshipped our ancestors, relatives would gather at the dining table and reminisce about how great-grandfather and grandfather left China and settled first in Thailand and then in Singapore. My great-grandfather used to leave a pot of tea in front of the provision shop for passers-by to quench their thirst. Whenever he was free, grandfather would also teach the village children how to read and write Chinese, using a large blackboard in the backyard of the house. Behind the blackboard, there was once a chicken coop which was later converted into a storage space. This used to be our favourite hide-and-seek spot.

Besides homecooked Chinese food, we also had the opportunity to savour delectable delicacies prepared by the Malay villagers during weddings and Hari Raya. I remember accompanying my fifth aunt to a little house up the street to purchase freshly cooked Malay kueh (cakes). They were prepared by an elderly Malay lady, who would sell them at the bus terminal at the end of Sembawang Road to supplement her family’s income.

I looked forward to such trips as her house exuded a heavenly fragrance of pandan (screw pine) and gula melaka (palm sugar) that wafted out from a small pot. She would patiently stir the fragrant syrup on a small charcoal stove while kneading dough. My aunts learnt to cook Malay cuisine from the Malay villagers. I recall running to the beach with a bamboo sieve to scoop shrimps for my fourth aunt to add to the bubbling mee siam (a soupy noodle dish of rice vermicelli in a spicy, sweet and tangy gravy, with toppings like sliced hard-boiled egg, chives, bean sprouts and fried bean curd) gravy that she had prepared.

My Grandfather’s Provision shop

As my grandfather’s provision shop was the only one in the village selling daily necessities, villagers often showed up at the shop. Some would purchase items on credit, while children dropped by multiple times within one day for small purchases. To protect the canned food from moisture and the salt particles in the sea breeze, my grandfather wrapped them in plastic bags. The Malay customers seemed to understand my grandfather’s heavy Teochew-accented Malay. For the longest time, I mistakenly thought that my grandfather’s name was sinkeh. It was only later when I realised that this term, which means “new guests”, was used to describe early Chinese migrants.

There was a kerosene tin in front of the shop where villagers would pay and fill up their recycled glass bottles with kerosene to light up their home lamps. Inside the shop, my grandfather used a simple pulley system made from two Milo cans suspended from the ceiling to contain loose change. By the time my cousins and I were tall enough to reach the Milo cans, we were allowed to help in the shop.

There was a small storeroom next to the shop where bags of rice were kept. We often found sparrows pecking at the gunny sacks for rice grains. On a few occasions, we even caught newly born, peanut-sized and hairless baby rats. Whenever the storeroom became very quiet and had a bad odour, it was a sure sign that a python had claimed the space as its home and someone would have to hunt down, trap and kill the snake.

The provision shop was also a place where people met and caught up with one another. The womenfolk loved to share cooking tips at the shop, speaking in a smattering of Teochew and Malay. Even the men who made deliveries would enjoy a quick chat with everyone around and use the opportunity to promote their products and the occasional free gift.

Business picked up when Sembawang Park opened at the end of Sembawang Road in 1979.2 Crowds started appearing, with visitors buying snacks and drinks from the provision shop. They were curious about the shop, and some even attempted to enter the kitchen and living quarters through the shop’s inner passageway.

Occasionally, we would also welcome foreigners sailing along the Johor Strait. They would moor their sailboats in the middle of the sea and rest for a few days. Then they would borrow a sampan (a small wooden boat) belonging to the Malay villagers and row to the shore to buy groceries from my grandfather’s provision shop. We would take the opportunity to chat with them in English and listen in wonder as they regaled us with their adventures out at sea.

At the end of each day, one of my aunts would pull shut the metal grille sliding door, slotting the heavy wooden panels into the respective openings along the wooden frame and then latching the door with a long wooden pole. However, we would still get occasional visits from villagers requesting to buy some items that they needed even when the shop had closed for business. Even though we were closed, we would still get the item out of the shop for them.

The End of Kampong Life

In the 30 years after Singapore gained Independence in 1965, urban redevelopment took place rapidly and drastically transformed the physical landscape of Singapore. The 1966 Land Acquisition Act allowed the government to acquire private land for housing, commercial and industrial purposes. Between 1959 and 1984, a total of 177 sq km of land were acquired, constituting about one-third of the total land area of Singapore then.3

To optimise land use, careful planning is required to develop large-scale housing and industrial projects. Other factors for consideration include safeguarding land for future use, developing blueprints to stimulate Singapore’s economic growth and improving the quality of life for all Singaporeans.4 With assistance from the United Nations Development Programme consultants, the government announced the first concept plan in 1971 that would guide the framework for infrastructure development and land use. This included provisions for the future growth of new industrial areas in Sembawang and Seletar.5

Kampong living became a thing of the past as villages were razed and people were resettled in high-rise Housing and Development Board flats. Kampong Wak Hassan, too, was not spared the wrecking ball. My grandfather’s provision shop and adjoining house were demolished in the early 2000s. On the site of the former kampong today is Watercove, an exclusive estate of 80 freehold luxury strata houses by the sea.

In the past, people lived near the sea for their livelihood. Today, living by the sea is a coveted life of luxury for city dwellers.

Ang Seow Leng is a Senior Librarian with the National Library, Singapore. Her responsibilities include managing the Singapore & Southeast Asian Collection, developing content as well as providing reference and research services relating to Singapore and Southeast Asia.

Ang Seow Leng is a Senior Librarian with the National Library, Singapore. Her responsibilities include managing the Singapore & Southeast Asian Collection, developing content as well as providing reference and research services relating to Singapore and Southeast Asia.NOTES

-

“甘榜華哈山路開放 李炯才主持儀式” [Kampong Hua Hasan Road opens, Li Jiongcai presides over the ceremony], 星洲日報 [Xingzhou Ribao], 18 July 1966, 8. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Sembawang Park to Occupy 10 Hectares,” Straits Times, 8 May 1979, 9. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Land Acquisition Act Is Enforced,” National Library Online, accessed 1 November 2023. ↩

-

Singapore (Singapore: Ministry of Information and The Arts, 1998), 187. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 959.57 SIN) ↩

-

“Singapore’s First Concept Plan Is Completed,” National Library Online, accessed 1 November 2023. ↩