Continuities and Changes: Singapore as a Port city Over 700 Years

Strategically situated at the southern tip of the Malay Peninsula, Singapore’s history as a port city stretches back to the 13th century.

Situated at the southern tip of the Malay Peninsula, the waters around Singapore have, as early as the 14th century AD, been recognised by maritime navigators as strategic in international navigation, marking the access point between the South China Sea and the Indian Ocean. The key factor that underpinned this strategic significance was the development of a direct Indian Ocean-South China Sea trade, linking the economies of the West, the Indian Ocean littoral and the South China Sea.

Less known, however, is Singapore’s long historical legacy as a port. Although the history of Singapore in the 19th and 20th centuries, first as a colonial port-city and then as an independent state that has managed to maintain its position as one of the busiest ports in the world, is well represented by a significant amount of literature, its historical legacy as a port prior to the 19th century has not been sufficiently explored.

Singapore’s port functions, especially those of the last two centuries, had largely been generalised into those of an entrepot and staple port servicing the Malay Peninsula hinterland, when in fact, the port played a myriad of roles that were quite different from these. These roles have also remained fairly consistent despite the evolving nature of the regional and international forces that had swept through Singapore over the course of more than seven hundred years. What were they, and how did they define Singapore as a port in the longue durée of history?

Singapore as an Indigenous Port Before 1819

Some time in the late 13th century, an autonomous settlement was established on the north bank of the Singapore River. Known as Singapore, the settlement depended almost entirely on external sources for both its wealth and provisions. It was the only port in the Southern Malacca Straits region, and serviced ships and traders peddling in the region. It competed against rival ports along the Malacca Straits coast, such as Palembang, Jambi, Tamiang, Kota Cina, South Kedah, Lambri and Semudra, for a slice of the maritime trade pie.

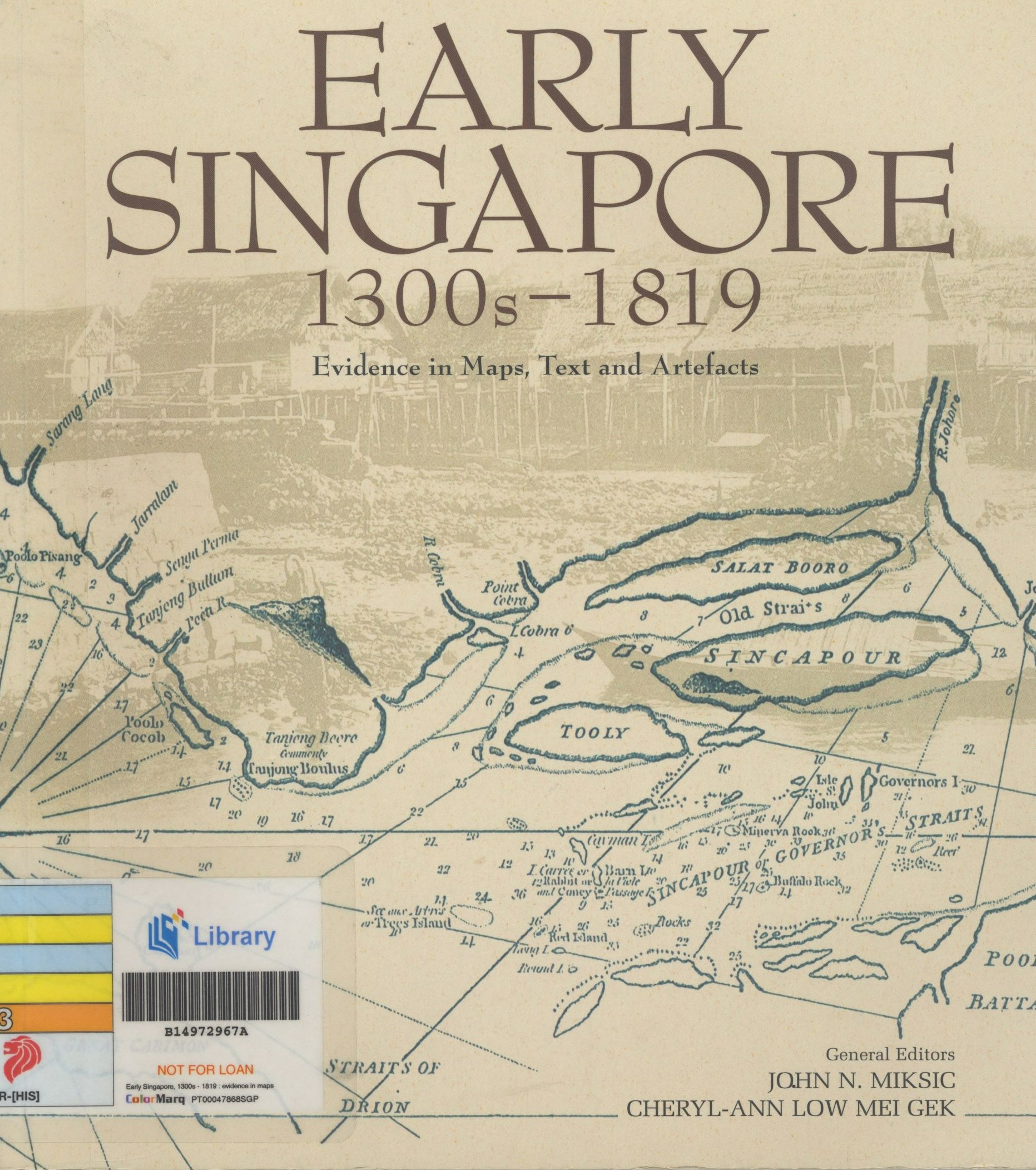

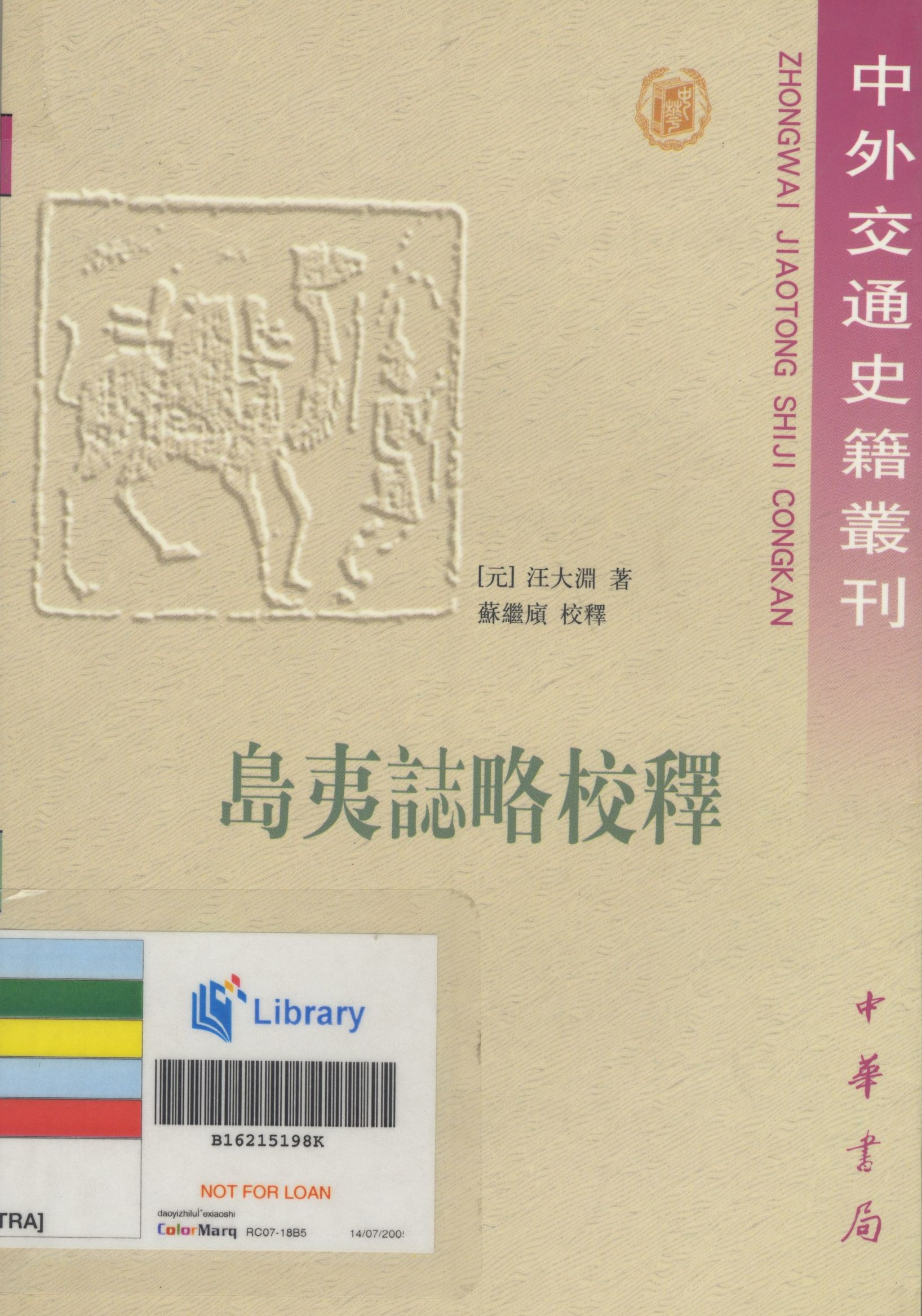

Singapore’s port functions were two-fold. Firstly, by making available several products that were in demand by the international markets, it attracted foreign traders to its port. According to the Daoyi Zhilue Jiaoshi, a Chinese account of the ports in Southeast Asia and the Indian Ocean littoral, written by the Chinese trader Wang Dayuan some time in the mid–14th century, these were namely top quality hornbill casques, middle quality lakawood and cotton. The niche market was successfully established as these products, which were commonly found at other Southeast Asian ports, were unique in terms of their quality.

Secondly, it established itself as the gateway into the international and regional economic system for its immediate peripheral region. The immediate region, particularly South Johor and the Riau Archipelago, was a catchment area for Singapore’s export products. In return, Singapore was the key source of foreign products to this region. Singapore was at the apex of this relationship, exerting a significant economic influence over the immediate region. This is substantiated by archaeological artifacts such as ceramics and glassware recovered from the Riau Archipelago.

During this period, Singapore played only a minor role as a transshipment hub in international trade. Only one transshipment product was known to have been made available for export by Singapore – cotton – which could have originated either from Java or India.

By the 15th century, Singapore had declined as an international trading port in the face of the ascendance of the Malacca Sultanate. However, evidence revealed that international trade continued to be conducted on the island. A map of Singapore, drawn by the Portuguese Mathematician Manuel Godinho d’Eredia, shows the location of a sharbandar’s office (the office of the Malay official responsible for international trade). Shards of Thai ceramics of the 15th century, and late 16th or early 17th century Chinese blue and white porcelain shards, were also recovered at the Singapore River and Kallang River.

Besides trading internationally, Singapore also provided other ports in the region with indigenous products that were demanded by the international markets. Blackwood (a generic term used by Europeans to indicate rosewood timber) was exported by Singapore to Malacca, which was in turn purchased by Chinese traders and shipped to China for use by the furniture-making industry.

Pre-1819 Singapore’s role as an international trading port, which lasted for more than three hundred years since the late 13th century, came to an abrupt end in the early 17th century, when the island’s main settlement and its port was destroyed by a punitive force from Aceh. There after, Singapore was devoid of any significant settlement or port until 1819, when Sir Thomas Stamford Raffles founded Singapore and reestablished an international port on the island.

Singapore as a Colonial Port-City (1819 to 1963)

Upon creating a strategic presence in Singapore, one of the first issues that Raffles dealt with was the establishment of a commercial port on the island. Identifying the Singapore River basin as the nascent location of international trade, Raffles was keen to attract both Asian and European traders to the new port. Land along the riverbanks, particularly along the south banks of the river, was reclaimed where necessarily, and allotted to Chinese and English country traders to encourage these capitalists to establish a stake in the newly founded port-settlement. While the Chinese traders, because of their frequent commercial interactions with Southeast Asian traders through the course of the year, set up their trading houses along the lower reaches of the Singapore River, the English country traders, who depended on the annual arrival of trade from India for their livelihood, set up their warehouses along the upper reaches of the river.

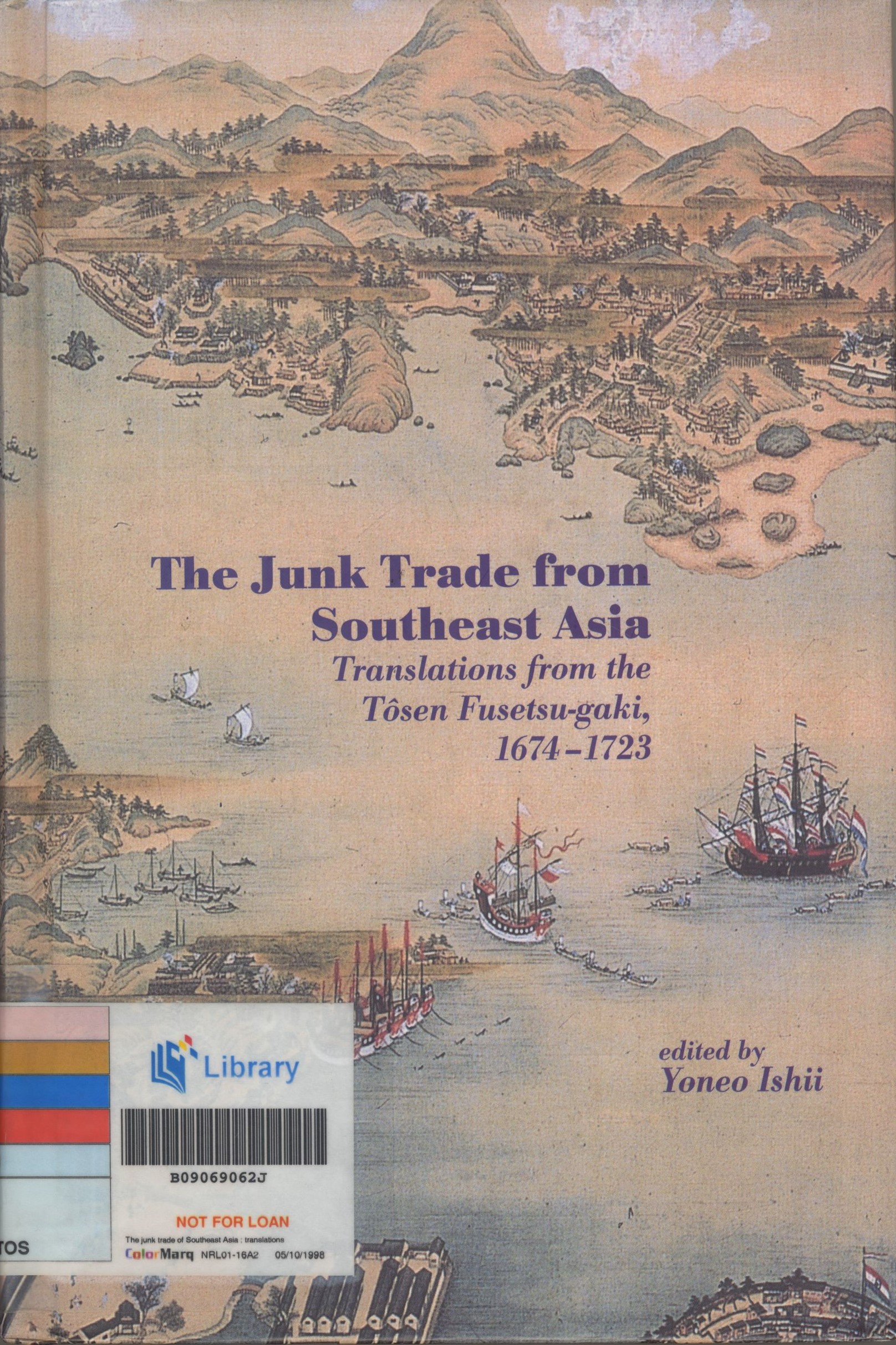

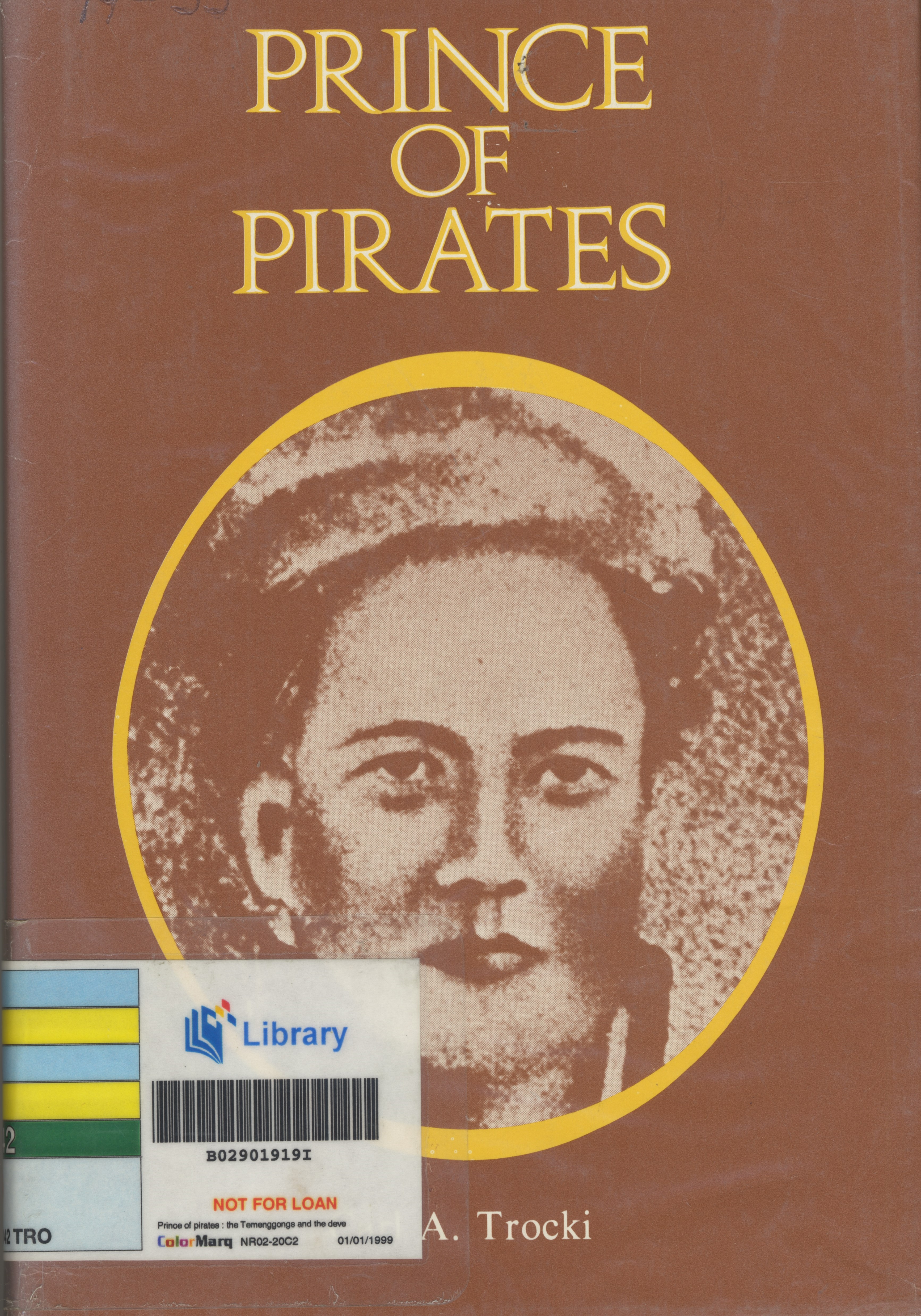

The nature of Singapore’s port trade, at least up until the late 19th century, was very much the same as that of coastal Southeast Asia. The port relied on three main networks of trade that were existent in Southeast Asia during that time for its economic viability: 1) the Chinese network, which linked Southeast Asia with the southern Chinese coastal ports of Guangdong and Fujian; 2) the Southeast Asian network, which linked the islands of the Indonesian Archipelago; and 3) the European and Indian Ocean network, which linked Singapore to the markets of Europe and the Indian Ocean littoral. These networks complemented each other, positioning Singapore as the transshipment point of the regional and international trade. By the 1830s, Singapore had overtaken Batavia (present-day Jakarta) as the Maritime Southeast Asian centre of Chinese junk trade, even as it very quickly became the key centre of English country trade in Southeast Asia. These developments were supported by the growth of Southeast Asian shipping in Singapore. Southeast Asian traders preferred the free port of Singapore to the cumbersome restrictions that were imposed by the authorities of the other major international ports of the region.

Singapore also served as the regional economic gateway for the immediate region. By the 1830s, Singapore supplanted Tanjung Pinang to become the export gateway for the gambier and pepper industry of the Riau-Lingga Archipelago, and by the 1840s, of South Johor as well. Singapore also became the centre of the Teochew trade in marine produce and rice. The range of products that were made available for export was limited but unique, mirroring the state of affairs in the late 13th to early 17th centuries.

As the volume of Singapore’s maritime trade increased through the course of the 19th century, Singapore also began to develop additional port functions. Singapore’s position as an increasingly important trading port in Southeast Asia, coupled with its strategic location, enabled it to develop into a vital nodal point in the network of Asian and international shipping. Sailing vessels, and in the mid-19th century, steam vessels, used Singapore as a key port-of-call in their passage along the Asian sea routes. Thus, from the 1840s onwards, Singapore became an important coaling station for the steam shipping networks that were beginning to develop.

Towards the late 19th century, Singapore as a port developed another important economic function – that of a staple port servicing a geographical hinterland. Following the instituting of the British Forward Movement in the Malay Peninsula in late 19th century, Singapore became the administrative capital of British Malaya. The Malay Peninsula began to be systematically exploited for its natural resources, and Singapore, because of its role as a nodal point in the regional and international shipping networks, was developed to be the staple port and international export gateway of the Malayan hinterland. Transportation networks, both roads and railways, were developed to transport primary products, such as tin, rubber and crude oil, from different parts of the Malay Peninsula to Singapore to be processed into staple products, and then shipped to Britain and other international markets. This role, which was never played by any of the previous ports of Singapore, quickly became the most important one that came to characterise the port of Singapore during the colonial period.

Back to Our Roots: Singapore as an Indigenous Port Once Again (1963–)

In 1963, Singapore merged with Malaysia, ending approximately one hundred and fifty years of British colonial rule in Singapore. Although Singapore remained part of the Malay Peninsula, Singapore was no longer its administrative or economic capital. In addition, the processing of raw materials extracted in the Malay Peninsula, which was a vital aspect of Singapore’s colonial port function, was severely curtailed by the absence of a common market between Singapore and the Malay Peninsula states. Singapore once again became a port-city devoid of a geographical hinterland.

Today, Singapore continues to function as an important nodal point in the network of regional and international shipping. In an age of shipping conglomerates with international networks, however, Singapore is no longer a crucial port-of-call. Neighbouring regions could, and have established, comparable ports-of-call. Singapore therefore has had to compete, as it did historically, against other ports in the region to attract trade and shipping to call at its port. This has been done by making a range of products available for export to attract trade to the island. While Singapore does not possess any indigenous natural resources or products that are demanded by the international markets, the global consumer economy and globalisation have enabled Singapore to develop an export-oriented economy that is based on value-added manufacturing.

Devoid of a geographical hinterland since 1963, Singapore has successfully co-opted the regional and global markets as its virtual economic hinterland, successfully obtaining the raw or partially manufactured products needed for its value-added processing activities from these economies, and exporting the value-added products back into them through market access agreements such as the World Trade Organization directives and Free Trade Agreements. These manufacturing activities are not supported by domestic demand, but by external markets. The port acts as the gateway through which goods flow into the international markets. More recently, it has progressed to include activities such as the provision of financial and legal services as well as research and development, facilitating the already well-established port-related services conducted in Singapore.

The success of Singapore’s economic activities has led it to expand its economic space over time. Presently, Singapore has managed to build up an enlarged economic sphere along the lines of the Extended Metropolitan Region. In this structure, Singapore is the centre of an integrated system of economic activities. The centre serves as the gateway to the international economy, and where there is the highest concentration of human and money capital. The peripheral region, namely Johor and the Riau Archipelago, supports Singapore by providing completed products that can be made available for export via the port of Singapore. This relationship mirrors that of the late 13th to early 17th centuries when Singapore was a classical Malacca Straits region port-settlement, and in the 19th and 20th centuries when Singapore was a colonial port-city.

Singapore as a Port Through the Ages

It is evident from the overview of Singapore’s history as a port over the last seven hundred years that the phases of Singapore as a port were highly similar to each other. The roles they played and the functions that they performed to keep the settlements economically viable – roles and functions that transcend the course of time.

This is due, almost entirely, to the similarities in the external circumstances Singapore has had to face over the years. The absence of a geographical hinterland, and the absence of a land-based society, had compelled Singapore, in the past, to develop key characteristics that would enable it to surmount the constraints imposed on the viability of its ports. These characteristics include the making of unique products available for export through its port, building the port to be a maritime gateway of the immediate peripheral regions around Singapore, and attracting passing mercantile shipping to call at the port.

In the process, Singapore has changed the concept of “hinterland” to complement the unique characteristics of its ports - from that of a geographical land mass providing the urban centre and maritime gateway to the external world with natural resources that may be demanded by external markets, to a virtual economic hinterland based on market access for the procurement of raw materials and the export of value-added products. Particularly in the present-day context, Singapore as a port is no longer merely an outlet of a larger economic entity, as it was between the late 19th and mid-20th centuries, but a port-city that is integrated into, and dependent upon, the economic nexus of the regional and international economic world.

Asst. Professor

History Department

National University of Singapore

FURTHER READING

John N. Miksic, Archaeological Research on the “Forbidden Hill” of Singapore: Excavations at Fort Canning, 1984 (Singapore: National Museum, 1985). (Call no. RSING 959.57 MIK)

Describes the archeological finds at Fort Canning which reveal details of the influence of early Hindu Kingdoms on Temasek.

Kenneth R. Hall, Maritime Trade and State Development in Early Southeast Asia (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1985). (Call no. RSING 382.0959 HAL)

An attempt to look at early trade and the development of Southeast Asia as a whole. It begins with a conceptual evaluation of statecraft and trade in Southeast Asia, then elaborates further on the influence of Southern China on the northern Southeast Asian coastal states, with the rest of the book studying the influence of Srivijaya and Majapahit kingdoms on the political development of the Southeast Asian states.

Lynda Norene Shaffer, Maritime Southeast Asia to 1500 (Armonk: M.E. Sharpe, 1996). (Call no. RSING 959.01 SHA)

An introductory overview of the early maritime experiences in Southeast Asia including the influences from first century Funan and the Srivijaya and Majapahit kingdoms in pre-colonial times.

Roland St. John Braddell, A Study of Ancient Timesin [i.e. Times in] the Malay Peninsula and the Straits of Malacca and Notes on Ancient Times in Malaya (Kuala Lumpur: Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, 1989). (Call no. RSING 959.01 BRA)

Reprints from the MBRAS by Braddell on Malaya’s early maritime histories. The articles include reprints of ancient maps and detailed analysis of routes from China and India.

Sinnappah Arasaratnam, Pre-Modern Commerce and Society in Southern Asia: An Inaugural Lecture Delivered at the University of Malaya on December 21, 1971 (Kuala Lumpur: University of Malaya, 1972. (Call no. RSEA 382.095 ARA)

A slim volume based on the inaugural lecture at the University. It reviews trade between South and Southeast Asia between the 17th and 18th century and its relation with incoming European trade.