GeolGraphic: Celebrating Maps and Their Stories

“GeolGraphic”, a multi-disciplinary festival of exhibitions, installation artworks and lectures on the subject of maps takes place at the National Library from 16 January to 19 July 2015. Tan Huism explains why you should not miss this event.

This map is from Itinerarium Sacrae Scripturae (Itinerary of Holy Scripture), written by the 16th-century pastor and theologian, Heinrich Bunting. The map shows the continent of Asia as Pegasus, the winged horse in Greek mythology. The book, which features the Bible written in the form of a travel account, was first published in 1581. Another map in the book depicts the world in the shape of a three-leaf clover with the scared city of Jerusalem in the centre and with Asia, Europe and Africa as leaves. National Library of Singapore Collection.

This map is from Itinerarium Sacrae Scripturae (Itinerary of Holy Scripture), written by the 16th-century pastor and theologian, Heinrich Bunting. The map shows the continent of Asia as Pegasus, the winged horse in Greek mythology. The book, which features the Bible written in the form of a travel account, was first published in 1581. Another map in the book depicts the world in the shape of a three-leaf clover with the scared city of Jerusalem in the centre and with Asia, Europe and Africa as leaves. National Library of Singapore Collection.

“You can render space and suspend time.” So writes American author Ronlyn Domingue of the powers of the map-maker, or cartographer, in her fantasy novel The Mapmaker’s War.1

The act of graphically representing the world around us is an early human impulse – judging from the prehistoric engravings of landscapes found in caves and rock shelters.2 Perhaps the earliest surviving example of a world map is a 2,600-year-old clay tablet3 dating to around 600 BCE, representing a Babylonian’s view of the world. Some might debate that the tablet cannot be considered a map as it is neither drawn to scale nor does it accurately capture the geographical landscape – for example, the river Euphrates is drawn as a set of parallel lines. From a scientific perspective, this clay tablet would certainly not qualify as a map. What, then, constitutes a map?

According to J.B. Harley and David Woodward, editors of a multi-volume series History of Cartography first published in 1987, “maps are graphic representations that facilitate a spatial understanding of things, concepts, conditions, processes, or events in the human world. “4 Most scholars who study maps have come to accept this definition of a map. This inclusive definition challenges the generally accepted view of maps as utilitarian, geographical and scientific, and its evolution as a move towards objective “truth”. It opens up the discourse on maps as objects that combine both the visual and the textual, as shaped by their makers. Maps need not depict places that are found on our physical earth, such as cosmological maps of paradise and other worlds, nor do they have to be tangible in the way the maps in our smart phones are.

All maps are, in a sense, mental maps as they reflect not only the cultural and historical backgrounds but also the personal perspectives of their makers. This is because maps are simplified representations of space within which map-makers have to decide what details to include or exclude. Maps that claim to provide “accurate descriptions” of a place may be overstating their assertion.5 Aside from reflecting the worldview of the map-maker, maps can be used to reinforce accepted values and power structures.

Maps, atlases and globes are often used metaphorically to represent power (real or imagined) and domination over territories. For instance, Queen Elizabeth I has been depicted in a portrait standing on the map of the British Isles,6 and in other paintings with her hand poised over a globe. In ancient China,the handing over of maps by the defeated state was a sign of submission to the victor,7 and 17th-century Mughal emperor, Jahangir, was depicted in portraits as standing atop a terrestrial globe.8

Painting of the fourth Mughal emperor, Jahangir, standing atop a terrestrial globe. The Trustees of the Chester Beatty Library, Dublin (CBL /n07A. 15). www.cbl.ie ©

Painting of the fourth Mughal emperor, Jahangir, standing atop a terrestrial globe. The Trustees of the Chester Beatty Library, Dublin (CBL /n07A. 15). www.cbl.ie ©

Maps have a special significance in Singapore. Given the dearth of historical material on Singapore before the arrival of Stamford Raffles in 1819, pre-19th-century maps depicting the island act as important visual records of our early origins. The National Library’s latest exhibition, “Land of Gold and Spices: Early Maps of Southeast Asia and Singapore”, provides visitors with the unique opportunity to view these rare early maps. This exhibition is part of a larger festival of maps and mapping called “GeolGraphic: Celebrating Maps and Their Stories”.

“GeolGraphic”, which is a curated combination of exhibitions and programmes, explores the diverse world of maps and showcases the collections of the National Library (NL) and the National Archives of Singapore (NAS), as well as mapping-related artworks by four Singapore artists. 9

This 19th-century chart with place names written in Bugis script is a rare example of an extant map of the region drawn by an unnamed Southeast Asian cartographer. Some early maps of the region drawn by Europeans are believed to have been based on indigenous maps and sources. In turn, indigenous cartographic traditions were also influenced by European maps of the time. This nautical chart, believed to a pirate's map, shows heavy borrowings from Dutch maps. Courtesy of Univeristy of Utrecht Library.

This 19th-century chart with place names written in Bugis script is a rare example of an extant map of the region drawn by an unnamed Southeast Asian cartographer. Some early maps of the region drawn by Europeans are believed to have been based on indigenous maps and sources. In turn, indigenous cartographic traditions were also influenced by European maps of the time. This nautical chart, believed to a pirate's map, shows heavy borrowings from Dutch maps. Courtesy of Univeristy of Utrecht Library.

Land of Gold and Spices: Early Maps of Southeast Asia and Singapore

This anchor exhibition for “GeolGraphic” reveals how Southeast Asia was perceived, conceived and mapped by the Europeans from the 15th to the early 19th centuries. The exhibition starts off with maps based on Geography, the seminal work of the 2nd-century Greek astronomer and mathematician Claudius Ptolemy. Ptolemy plotted out what he considered as the known terrestrial world at the time. The region we now know as Southeast Asia was for Ptolemy “India Beyond the Ganges” – a land where gold, silver and other exotic products abounded In 13th-century Europe, the tables of longitudes and latitudes from Geography were translated into maps to accompany the text, first in manuscript form and, later, in the 15th century, in printed editions. These maps constitute some of the earliest European depictions of Southeast Asia. Eventually, the lure of spices and riches brought the Portuguese, Spanish, Dutch and British to the region and their intrepid journeys can be explored through the various maps displayed at the exhibition.

A highlight of the exhibition are several pre-1800 maps that contain names such as Cinca pula, Cingatola and Sincapura. Could these names refer to Singapore? Also on display are early printed and hand-drawn maps that identify Singapore as Old Strieghts of Sincapura, lantana, Pulo Panjang and Sincapour. Whatever the names used, these maps clearly point to Singapore’s existence before 1819 and offer a glimpse into its maritime history. Another highlight are the rare hand-drawn Dutch and English maps that have been borrowed from European libraries and displayed in Singapore for the first time.

Island of Stories: Singapore Maps

Do you know where “zero point” is located in Singapore? Or where the “circus” at Orchard Road was found? “Island of Stories” draws on an eclectic mix of Singapore maps that capture intriguing moments from our country’s history. This exhibition, organised by NAS and NL, showcases the NAS’ map collection. Accompanied by images and audiovisual elements, the exhibition weaves a multifaceted story of Singapore’s past.

On display are maps that depict Singapore’s farmland and soil composition; stories of the detached mole (breakwater that provides a safe protected area for smaller ships to anchor) at Marina Bay; the election fever of 1955; 3-D aerial photogrammetry; and alternative urban concepts for Singapore.

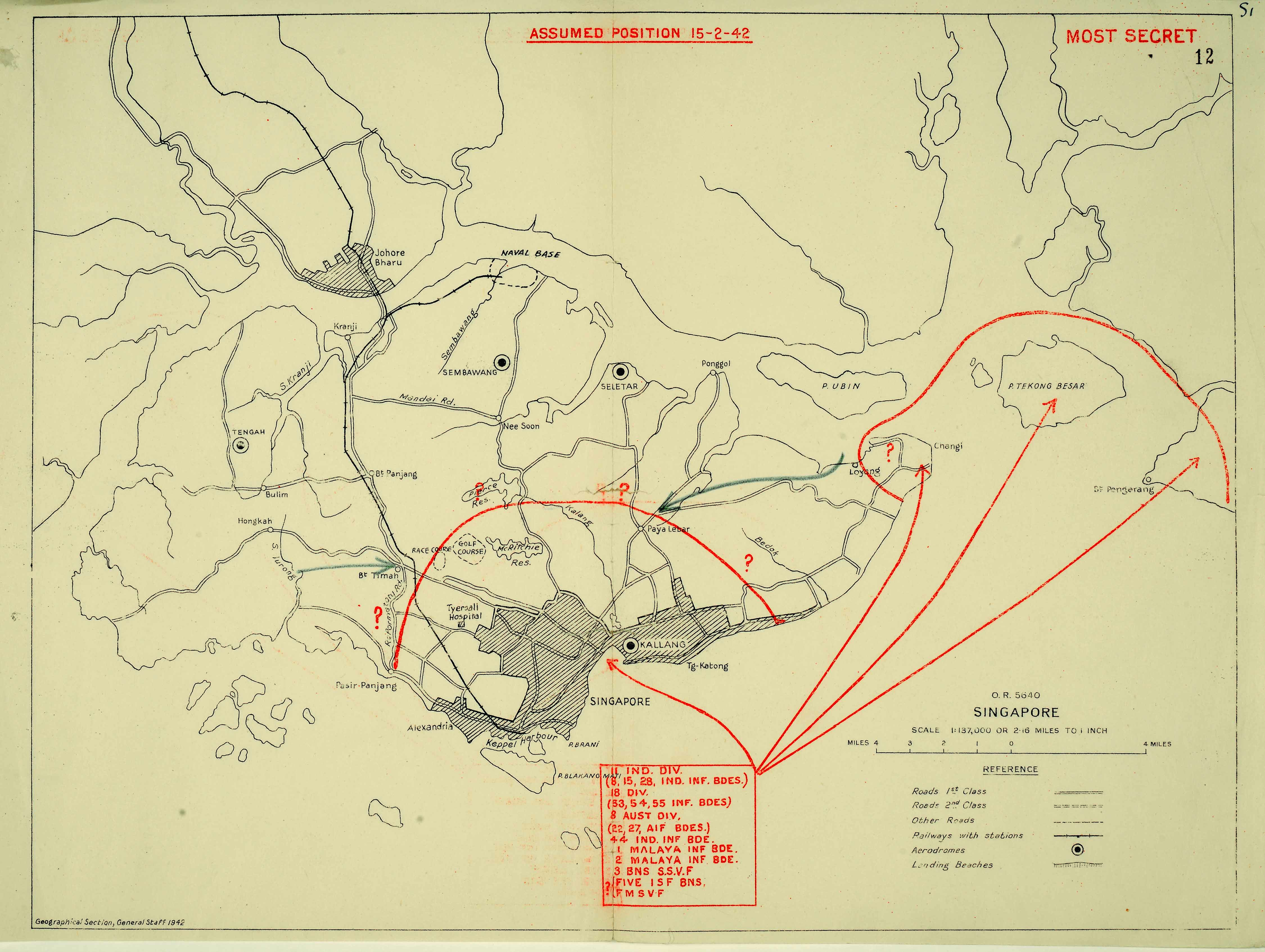

A special Geographic Information System (GIS) developed with the Urban Redevelopment Authority enables visitors to overlay maps from the mid-19th century over a contemporary map of Singapore to see how our landscape has radically changed over the years. Another highlight are three maps drafted by the British army during the Malayan campaign and the Battle for Singapore, which detail the movement and disposition of British and Japanese troops in Northern Malaya. This display, comprising rare maps on loan from the National Archives of the United Kingdom, commemorates the 70th anniversary of the end of World War II in 2015.

This 1977 map depicts the findings of the very first comprehensive soil survey of Singapore. It is still the only known officially commissioned soil map of Singapore to date. The island's central area is made of hard granite, indicated in pink. This natural feature has influenced much of the urban development on the island, with most of the construction work taking place outside this central zone made up of softer alluvium and sedimentary rocks. Survey Department, National Archives of Singapore Collection.

This 1977 map depicts the findings of the very first comprehensive soil survey of Singapore. It is still the only known officially commissioned soil map of Singapore to date. The island's central area is made of hard granite, indicated in pink. This natural feature has influenced much of the urban development on the island, with most of the construction work taking place outside this central zone made up of softer alluvium and sedimentary rocks. Survey Department, National Archives of Singapore Collection.

This map, on display at “Island of Stories: Singapore Maps” organised by NAS, shows the positions of the British (in red) and Japanese military units (in blue) on 12 and 13 February 1942. The Battle for Singapore began on 8 February and after four days of intense fighting, Japanese forces broke through the initial British defences and captured the western half of the island, as depicted on the map. The British eventually surrendered on 15 February 1942. Courtesy of National Archives of the United Kingdom; National Archives of Singapore Collection.

This map, on display at “Island of Stories: Singapore Maps” organised by NAS, shows the positions of the British (in red) and Japanese military units (in blue) on 12 and 13 February 1942. The Battle for Singapore began on 8 February and after four days of intense fighting, Japanese forces broke through the initial British defences and captured the western half of the island, as depicted on the map. The British eventually surrendered on 15 February 1942. Courtesy of National Archives of the United Kingdom; National Archives of Singapore Collection.

Sea State 8 Seabook: An Art Project By Charles Lim

seabook was conceived by artist Charles Lim as a site for the agglomeration of archival material, anecdotes and memories that explores Singapore’s relationship with the sea. Lim, who is Singapore’s 2015 representative to the Venice Biennale, has a close relationship with the sea as he is a former national sailor and represented Singapore in the 1996 Olympics.

Artist Charles Lim’s work, Sea Safe (2014), in progress.

Artist Charles Lim’s work, Sea Safe (2014), in progress.

This particular project is an extension of Lim’s previous solo-exhibition, “In Search of Raffles’ Light”, held in 2013 at the National University of Singapore (NUS) Museum. Both these projects are part of Lim’s body of work known as the SEA STATE series, which was first initiated in 2008 and continues with his exploration of Singapore’s maritime ecology. Developed together with the librarians at NL, seabook highlights the vast amount of information and data gathered from maps, charts and newspaper clippings, as well as scholarly material grappling with the complex relationship between Singapore and the sea – from colonial times to the present day. The stories encompass the mundane – such as fishing as a livelihood, the everyday lives of island communities, regulations on the use of the sea for leisure and other purposes, as well as sea-related tragedies, including an attack on a girl by a swordfish in 1961. The exhibition, jointly organised by NUS Museum and NL, highlights the troubled relationship Singapore has with its seas and its continued undercurrents in our lives.

Artist Charles Lim working on seabook with NL librarian, Janice Loo.

Artist Charles Lim working on seabook with NL librarian, Janice Loo.

Mind the Gap: Mapping the Other

Making up the art component of “GeolGraphic” is “Mind the Gap”, which presents the works of three Singapore contemporary artists, who harness data collection and mapping to investigate what lies beneath the surface of contemporary life.

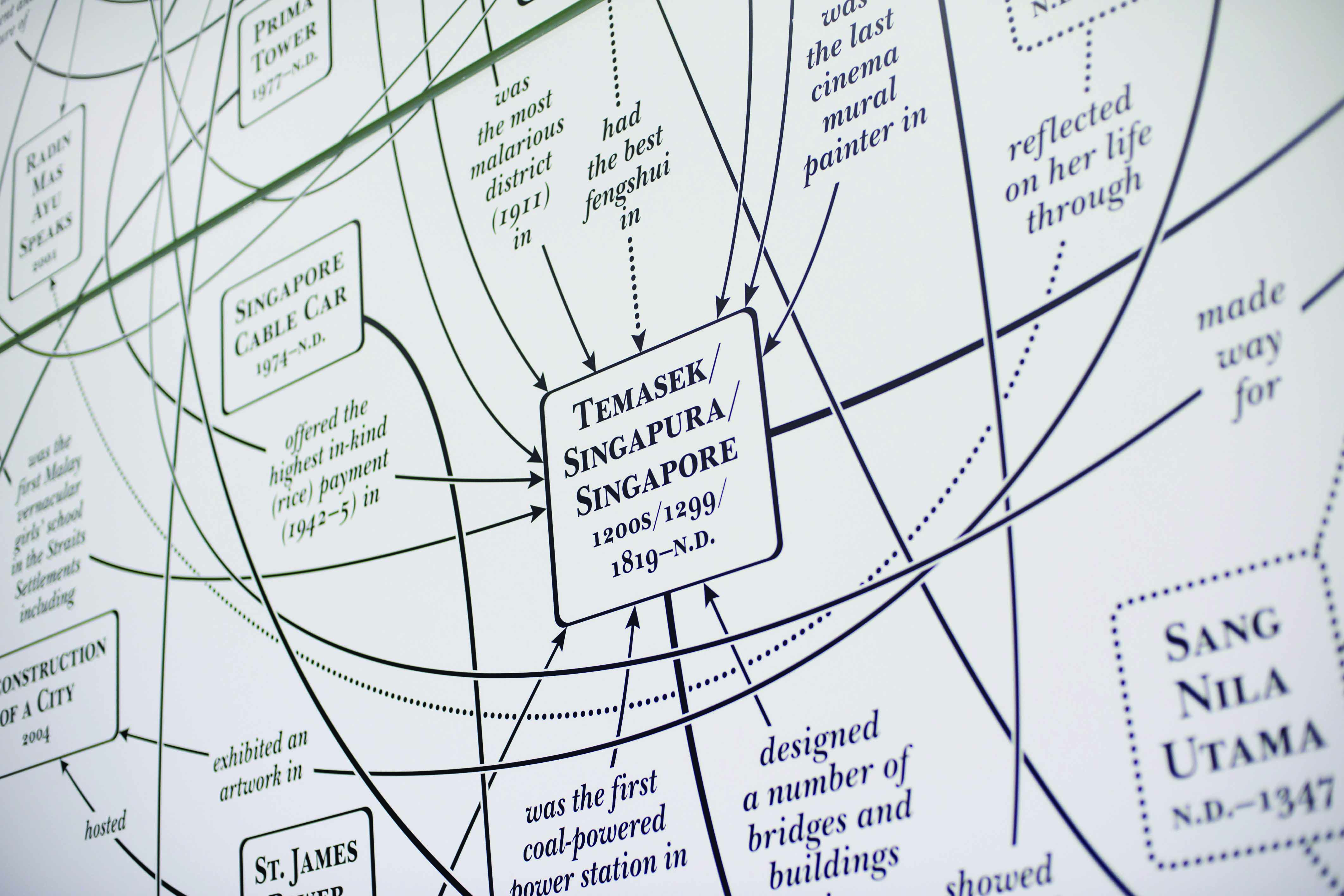

Bibliotopia by Michael Lee

Michael Lee’s research interest focuses on urban memory and fiction, emphasising their contexts and issues of loss. He translates his findings into diagrams and texts, in particular, the mind map. Lee finds the mind map powerful in generating ideas and organising vast amounts of data. In Bibliotopia, Lee uses the device of the mind map to uncover the “secret bookscape” of Singapore’s book culture. Focusing on the genres of short fiction, horror and the teen novel through the literary output of Catherine Lim, Russell Lee and Adrian Tan, he seeks to draw out secrets that are hidden within, or exposed by, narratives on identity, adolescence and the ghostly in Singapore.

Close-up of Michael Lee’s Notes Towards a Museum of Cooking Pot Bay (2010–11), from his artwork, Bibliotopia.

Close-up of Michael Lee’s Notes Towards a Museum of Cooking Pot Bay (2010–11), from his artwork, Bibliotopia.

Outliers by Jeremy Sharma

In the installation work Outliers, by multidisciplinary artist Jeremy Sharma, are four white polystyrene blocks with undulating surfaces that capture in material form the signals of dying stars. When dying stars explode, their remnants (also known as pulsars) emit electromagnetic pulses that can be detected by a radio telescope on earth. These pulses are emitted until the star finally burns out, which could take anything between 10 and 100 million years.

With the help of a pulsar scientist, Sharma has been collecting and categorising radiographic data of selected pulsars according to size, distance from earth and age at the time of discovery. This two-dimensional data was then converted into 3-D landscapes of valleys and peaks created by 3-D printing technology.

Outliers contemplates the profound space-time distance the signals of dying stars travel in order to communicate their death throes.

A polystyrene block is given a textured surface in Jeremy Sharma’s Outliers (2014–2015).

A polystyrene block is given a textured surface in Jeremy Sharma’s Outliers (2014–2015).

the seas will sing and the wind will carry us (Fables of Nusantara) by Sherman Ong

Sherman Ong is a filmmaker, photographer and visual artist whose practice centres on the relationship between place and the human condition. In this video installation, he uses the documentary/ethnographic film genre to tell stories of migration, transborder identities, myths and memory in island Southeast Asia. The histories and contemporary stories of the region are explored through the stories of nine individuals featured in a series of video vignettes. The stories include an Acehnese living in Malaysia recounting the loss of his family in the Asian tsunami of 2004; a Peranakan (Straits Chinese) woman describing her life of servitude while waiting for the “right” man to come along; and a Chinese woman arriving in Singapore in search of a better life.

Stills from Sherman Ong’s work, the seas will sing and the wind will carry us (Fables of Nusantara).

Stills from Sherman Ong’s work, the seas will sing and the wind will carry us (Fables of Nusantara).

Tan Huism is Head of Exhibitions and Curation at the National Library of Singapore. She started her curatorial career at the National Museum of Singapore before moving to the Asian Civilisations Museum, where she became Deputy Director of Curation and Collections.

REFERENCES

Borschberg, P. (2010). The Singapore and Melaka Straits: Violence, security and diplomacy in the 17th century (pp. 60–112). Singapore: NUS Press. (Call no.: RSING 911.16472 BOR)

Domingue, R. (2013). The mapmaker’s war: Keeper of tales trilogy, Book 1. New York: Atria Book. Retrieved from overdrive books.

Harely, J.B., & Woodward, D. (Eds.). (1987). Preface. In The History of cartography: Cartography in the traditional east and southeast Asian societies (Vol 1, p. xvi). Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. (Call no.: RSING 526.09 HIS)

Smith, C. (1994). Prehistoric cartography in Asia. In J.B. Harley & D. Woodward (Eds.), The History of cartography: Cartography in the traditional east and southeast Asian societies (Vol. 2). Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. (Call no.: RSING 526.09 HIS)

Yee, C. (1994). Chinese maps in political culture. In J.B. Harley & D. Woodward (Eds.), The History of cartography: Cartography in the traditional east and southeast Asian societies (Vol. 2). Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. (Call no.: RSING 526.09 HIS)

NOTES

-

Domingue, R. (2013).The mapmaker’s war: Keeper of tales trilogy, Book 1 (p. 286). Oxford: Oxford University Press. (Call no.: RSEA 508.092 WAL) ↩

-

Smith, C. (1994). Prehistoric cartography in Asia. In J.B. Harley & D. Woodward (Eds.), The history of cartography: Cartography in the traditional east and southeast Asian societies. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. (Call no.: RSING 526.09 HIS) ↩

-

This clay tablet which was found in Iraw is now in the collection of the British Museum. ↩

-

Harely, J.B., & Woodward, D. (Eds.). (1987). Preface. In The history of cartography: Cartography in the traditional east and southeast Asian societies. (Vol 1, p. xvi). Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. (Call no.: RSING 526.09 HIS) ↩

-

See Monmonier, M.S. (1991). How to lie with maps. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. (Call no.: R 910.0148 MON) ↩

-

This oil painting known as “The Ditchley Portrait”, was painted around 1592. It is in the collection of the National Portrait Gallery, London. ↩

-

Yee, C. (1994). Chinese maps in political culture. In J.B. Harley & D. Woodward (Eds.), The history of cartography: Cartography in the traditional east and southeast Asian societies. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. (Call no.: RSING 526.09 HIS) ↩

-

A miniature painting of Jahangir standing on the globe shooting at his enemy, Malik Anbar, dated 1620 is in the collection of the Chester Beatty Library. Another painting of Jahangir standing on a globe shows him embracing Shah Abbas of Iran, dated 1618 is in the collection of the Freer Gallery of Art. ↩

-

Borschberg, P. (2010). The Singapore and Melaka Straits: Violence, security and diplomacy in the 17th century. Singapore: NUS Press. (Call no.: RSING 911.16472 BOR) ↩