On the Trail of Francis P. Ng: Author of F.M.S.R.

In her effort to republish one of our unknown literary treasures, Dr Eriko Ogihara-Schuck tracks down the elusive Francis P. Ng, author of possibly the first notable work of poetry in English by a Singapore writer.

In August 2014, I found myself in Singapore, the country where I came of age as a teenager. Twenty years had passed since I left Singapore to enter college in Japan and then higher degree studies in the United States and Germany. Initially, it felt as if nothing had changed since I left the city. The night sky was still the same over the East Coast, twinkling here and there with the strobe lights of airplanes heading towards Changi Airport. On terra firma, the songs and sounds of the National Day festivities quickly re-absorbed me into this country, exactly the same way they did when I first arrived as a 12-year-old girl in the summer of 1988.

Yet, many things had changed. Unfamiliar apartments and buildings had sprung up everywhere, and new shopping malls and changes inside once familiar buildings generated some anxiety. And there was a definite buzz to the city, with a lot more people than I remembered. I tried to recall and imprint in my memory scenes I was familiar with. But much as I was disturbed about losing my own memory of Singapore, I was equally concerned about the loss of one of Singapore’s literary treasures.

I had come back to Singapore to trace the footsteps of Francis P. Ng, a forgotten Singapore poet who disappeared at the outset of the Japanese invasion in 1942. Before arriving in Singapore, I had discovered that Francis P. Ng was a pseudonym for Teo Poh Leng, a local Chinese and the author of F.M.S.R. (1937),1 a poem that describes a train journey from Singapore to Kuala Lumpur on the Federated Malay States Railways (FMSR). F.M.S.R. has been claimed to be the first published book-length English poem by a Singapore author.

T.S. Eliot and the Singapore Connection

An “S” Class Express engine of the Federated Malay States Railways (FMSR), which was a rail operator that serviced British Malaya in the first half of the 20th century. The poem F.M.S.R. (published in 1937) describes a train journey from Singapore to Kuala Lumpur. Lee Kip Lin Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

An “S” Class Express engine of the Federated Malay States Railways (FMSR), which was a rail operator that serviced British Malaya in the first half of the 20th century. The poem F.M.S.R. (published in 1937) describes a train journey from Singapore to Kuala Lumpur. Lee Kip Lin Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

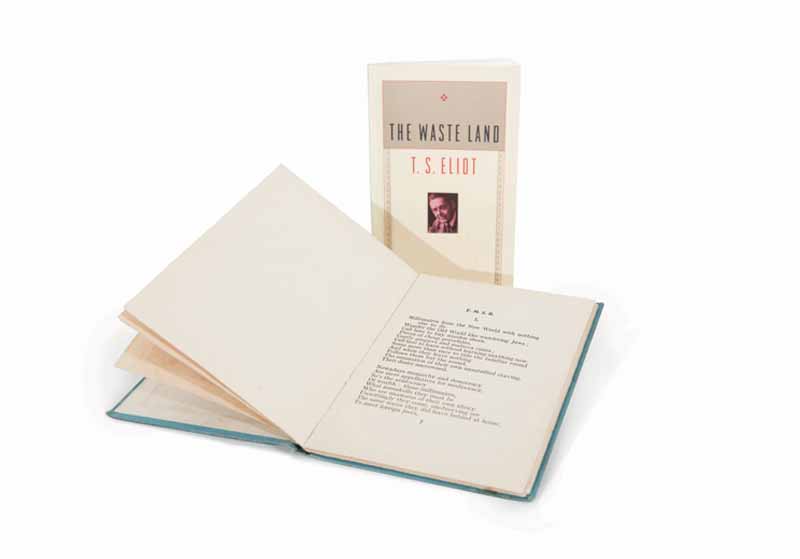

F.M.S.R. first came to my attention when I was preparing for a conference presentation on the poet T.S. Eliot (1888–1965), who was born in the United States and emigrated to Britain in 1914 at age 25. Eliot is well known for his modernist masterpiece The Waste Land (1922). Beginning with the unconventional phrase. “April is the cruellest month”, the poem caused a sensation in the world of Western poetry by introducing new styles of writing and perception. After teaching Eliot in an undergraduate American Studies course in Germany for many years, I wanted to make a scholarly contribution to the study of this poet by exploring the extent of his literary influence in Asia.

I started by researching Eliot’s impact on Japanese literature but quickly learned that many scholars had previously worked on this topic. My mind then turned to Singapore, where I had grown up as a teenager. I stumbled upon a Wikipedia entry on Singapore literature, and quite serendipitously, under the section on poetry. I learnt about F.M.S.R. being “a pastiche of T.S. Eliot”!2 According to Rajeev S. Patke’s and Philip Holden’s The Routledge Concise History of Southeast Asian Writing in English (2009) available on Google Books, the poem was influenced by The Waste Land.3

My curiosity was piqued and I became interested in reading and analysing F.M.S.R. partly because no substantial scholarly studies on it existed and I enjoy the challenge of writing about neglected literary treasures. As of today, Holden’s three-sentence description of F.M.S.R. as “one of the first of many efforts to tropicalize T.S. Eliot”4 in Writing Singapore (2009) amounts to the longest scholarly comment on the poem. However, I soon found that F.M.S.R. is a very difficult book to obtain – aside from the National Library of Singapore, only four other libraries abroad hold the book.5 No rare book dealer lists the text in its holdings.

Unable to borrow or obtain a copy of the book, I boarded a plane to London to peruse the poem at the British Library. Flipping through the pages of the faded book, I was moved by the poem’s density and innovative use of metaphors and imagery, reminiscent of what is found in Eliot’s poetic works. Indeed, The Waste Land resonates throughout this poem: while transforming its setting from London to the Malayan Peninsula, F.M.S.R. clearly inherits from The Waste Land its post-World War I pessimism about human deeds and progress, as well as its lamentation over materialism, urbanisation and industrialisation.

Perhaps even more striking was that F.M.S.R. does not simply emulate Eliot’s seminal work; by creating its own voice and sound, the poem generates what Teo would have called a “Malayan modernism” – one that differs markedly from Eliot’s. Focusing on this distinctive aspect, I crafted a scholarly paper and presented it at an American Studies conference held in Poland in August 2013.

As F.M.S.R. is an “orphan work” – meaning the copyright holder who is able to grant permission for reproduction is unknown – it hindered the usual routine of presenting a paper and developing it into a publishable scholarly article. Unfortunately, the copyright information and details of the author were destroyed when the office of his London publisher, Arthur H Stockwell, was bombed during World War II.6 As I could not locate any information about the author, I was unable to track down his family who would have inherited the copyright. Current laws on intellectual property rights state that copyright expires 70 years after the death of the author but, without the necessary biographical information on Teo, there was no way to ascertain when exactly he died, if indeed he is dead.

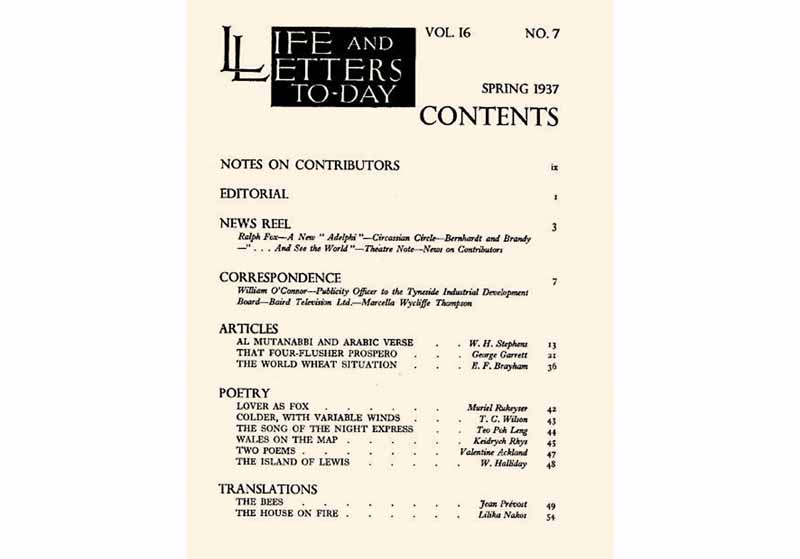

Then came my Eureka moment. As I started reading the peripheral information added to the poem. I noticed a footnote to Section VII of F.M.S.R., which stated that the section was published as an independent poem titled “The Song of the Night Express” in the 1937 spring issue of Life and Letters To-day, a British literary magazine.7 Curious to know if Section VII and “The Song” were identical. I decided to seek out “The Song”.

The data bore out. In Life and Letters To-day was Section VII of F.M.S.R., re-titled as “The Song of the Night Express”, which starts with “For he chánts of the whéels/ Of the whéels revolving, revolving”. But I also stumbled upon an unexpected surprise. The poem was attributed not to “Francis P. Ng” but to “Teo Poh Leng”.8 There was also a short biographical note about Teo, introducing him as having been born in 1912, serving as a primary school master in Singapore and having written poems that won the approval of British poet Silvia Townsend Warner and Cornish poet Ronald Bottrall.9

Suddenly in the face of precious information I had been unable to gather for half a year, a shiver of excitement pulsed through me. Who exactly was Teo Poh Leng? Why did he publish under a different name? Why did he publish his poem in the United Kingdom? With these questions swirling in my head, I spent countless hours at my desk, trawling the Internet for more details as well as reaching out to various Singaporeans with many inquiries.

A copy of F.M.S.R. and T.S. Eliot's The Waste Land. Both the poem and the poet influenced Teo Poh Leng to write his poem F.M.S.R., using the pen name Francis P. Ng. F.M.S.R. has been claimed to be the first book-length English poem by a Singapore author. National Library of Singapore is one of five libraries in the world that has this book. F.M.S.R., London: Arthur H Stockwell, 1937; The Waste Land, San Diego; Harcourt Brace & Co. All rights reserved, 1997.

A copy of F.M.S.R. and T.S. Eliot's The Waste Land. Both the poem and the poet influenced Teo Poh Leng to write his poem F.M.S.R., using the pen name Francis P. Ng. F.M.S.R. has been claimed to be the first book-length English poem by a Singapore author. National Library of Singapore is one of five libraries in the world that has this book. F.M.S.R., London: Arthur H Stockwell, 1937; The Waste Land, San Diego; Harcourt Brace & Co. All rights reserved, 1997.

Piecing Together a Puzzle: Teo’s Biography

Trawling through NewspaperSG, the digital newspaper database of the National Library Board (NLB), Singapore, to locate articles that contain the name Teo Poh Leng, I was able to ascertain that Francis P. Ng was a pseudonym that Teo adopted for F.M.S.R.. No wonder I could not find anything under Francis P. Ng! While I was still in Germany, I contacted librarian Tim Yap Fuan at the National University of Singapore (NUS), who was able to locate and make available to me pertinent materials from the NUS Central Library.

Now hopeful that more sources about Teo could exist in other Singapore institutions, I decided I had to make a trip here. Shortly after arriving in the city, I met up with Michelle Heng, a librarian at the National Library, who offered to do some “sleuth work” – running around the library and checking shelf after shelf in search of old sources.

Based on various fragmented sources I have been able to gather, thanks to these librarians and various Singapore official records, this is what I have pieced together on the life of Teo Poh Leng.

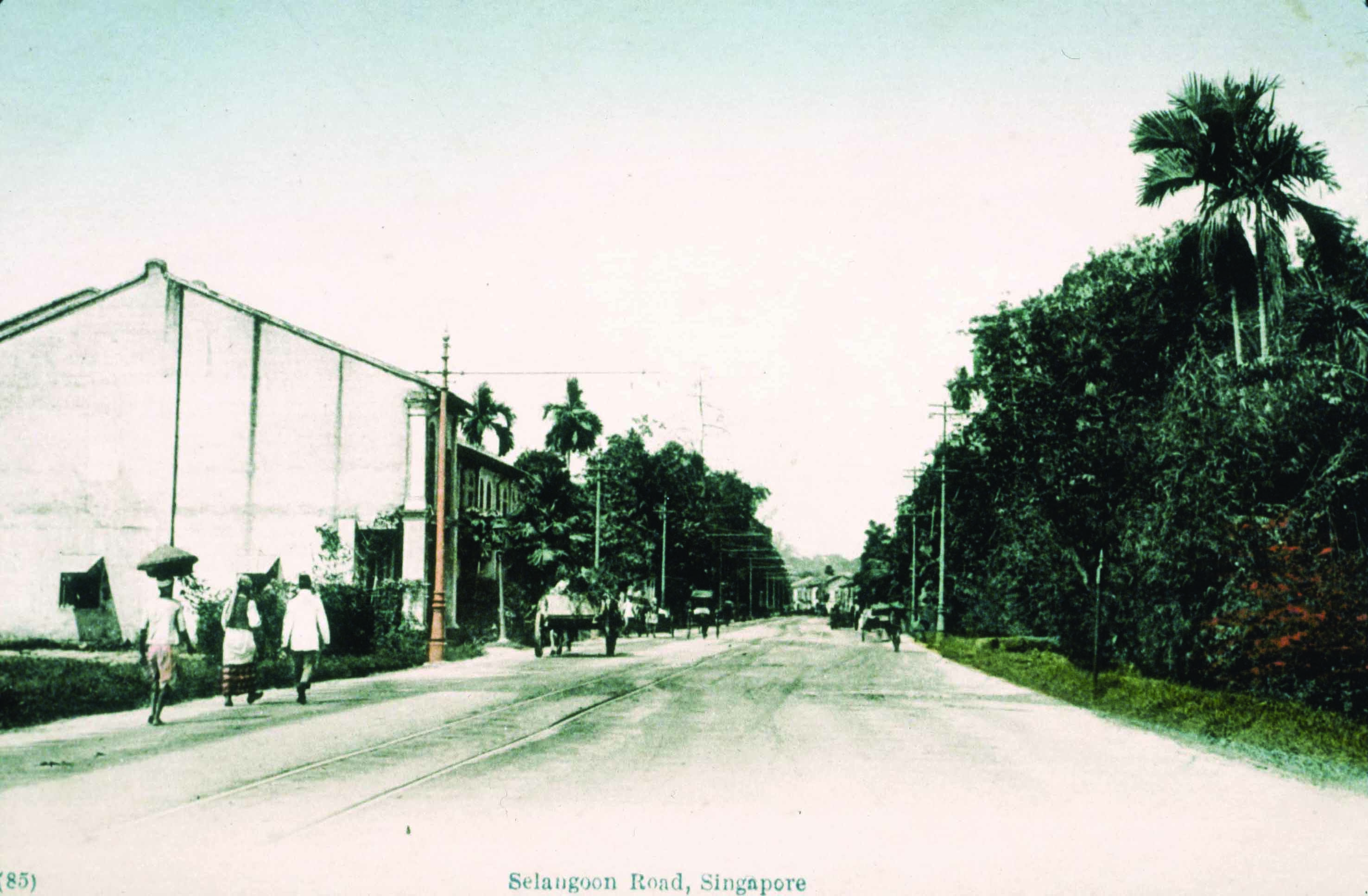

If the biographical note in Life and Letters To-day correctly affirms Teo’s birth year as 1912, then he was quite possibly born outside of Singapore. The Immigration & Checkpoints Authority of Singapore conducted a search for a birth certificate based on “Teo Poh Leng”, his pseudonym “Francis P. Ng” and his postal address of “700 Serangoon Road” – but no record was found. Neither could the Catholic Chancery archives of Singapore find a baptism record, although in his 20s Teo had been a member of the Catholic Young Men’s Association.10 Perhaps he was born in today’s Malaysia; after all in F.M.S.R. the traveller describes his journey to Kuala Lumpur, the Malaysian capital, as “coming home”. 11

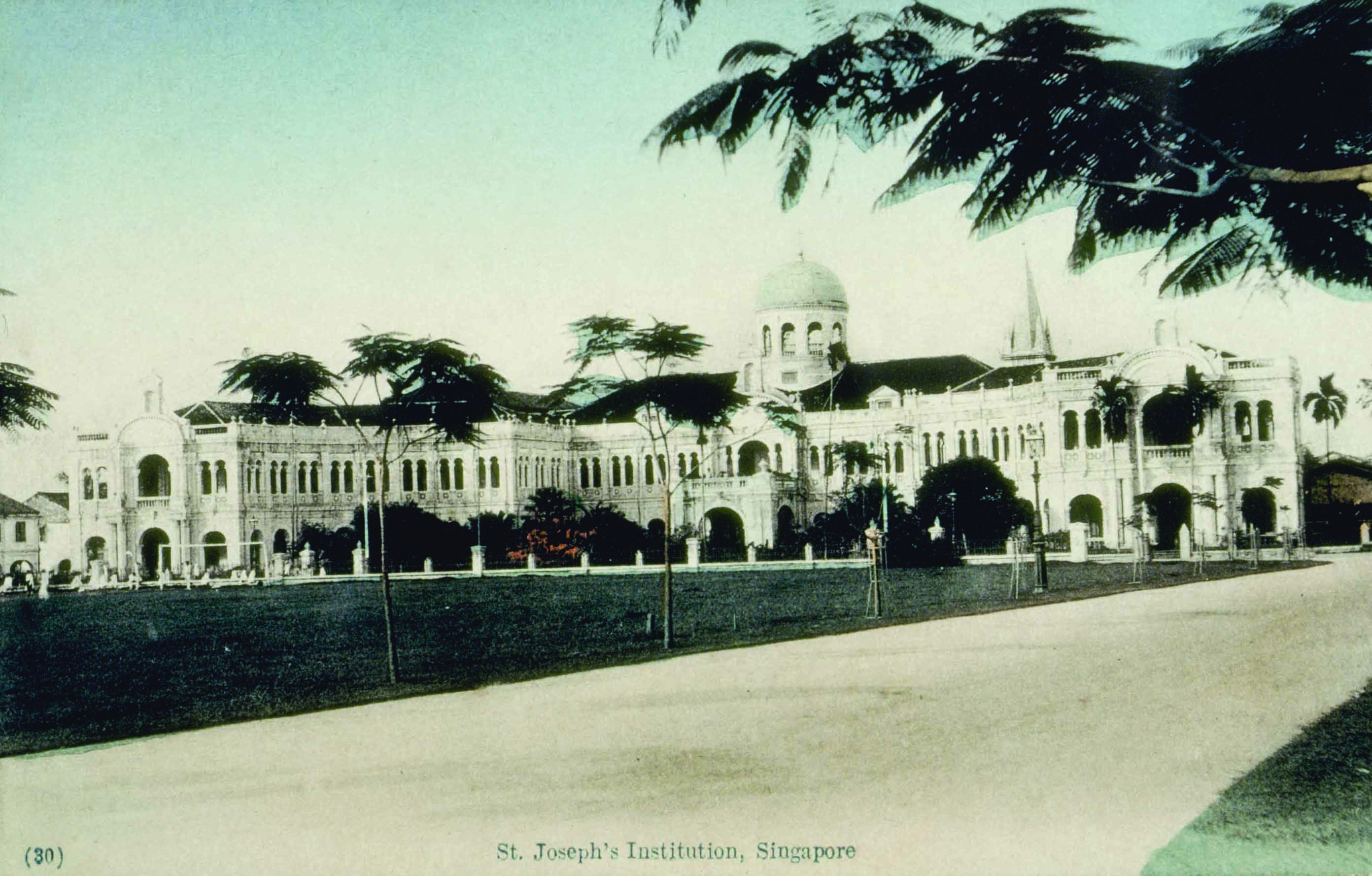

Evidence shows that Teo studied at St Joseph’s Institution (SJI). He took the School Certificate Examination in 1929.12 Cambridge examinations records, the only materials pertaining to Teo that SJI still holds, attest that he excelled in English literature. 13 Teo graduated together with Kenneth Michael Byrne, who later became a member of the first People’s Action Party cabinet in 1959. 14

Serangoon Road, circa 1911. At the time Serangoon Road was serviced by a single tram line running from Mackenzie Road depot to Paya Lebar. Teo very likely lived at 700 Serangoon Road in the early 1930s, today an empty plot of land just in front of the Kwong Wai Shiu Hospital. Arkshak C Galstaun Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Serangoon Road, circa 1911. At the time Serangoon Road was serviced by a single tram line running from Mackenzie Road depot to Paya Lebar. Teo very likely lived at 700 Serangoon Road in the early 1930s, today an empty plot of land just in front of the Kwong Wai Shiu Hospital. Arkshak C Galstaun Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

St Joseph’s Institution, circa 1912. Teo studied here and passed his School Certificate Examination in 1929. Arkshak C Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

St Joseph’s Institution, circa 1912. Teo studied here and passed his School Certificate Examination in 1929. Arkshak C Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

In 1931, two years after a civil service appointment, Teo was admitted to Raffles College at Bukit Timah Road, the precursor of the University of Malaya and NUS.15 Raffles College had opened only two years before to groom local university-educated school teachers at a time when schools were dominated by British expatriates. Teo entered the college together with Paul Abisheganaden (1914–2011), the first Singaporean choral and orchestral conductor: Lee Hah Ing (1914–2009), the former principal of Anglo-Chinese School; and Lokman bin Yusof (1914?–1972), the first Lord Mayor of the city of Kuala Lumpur. 16

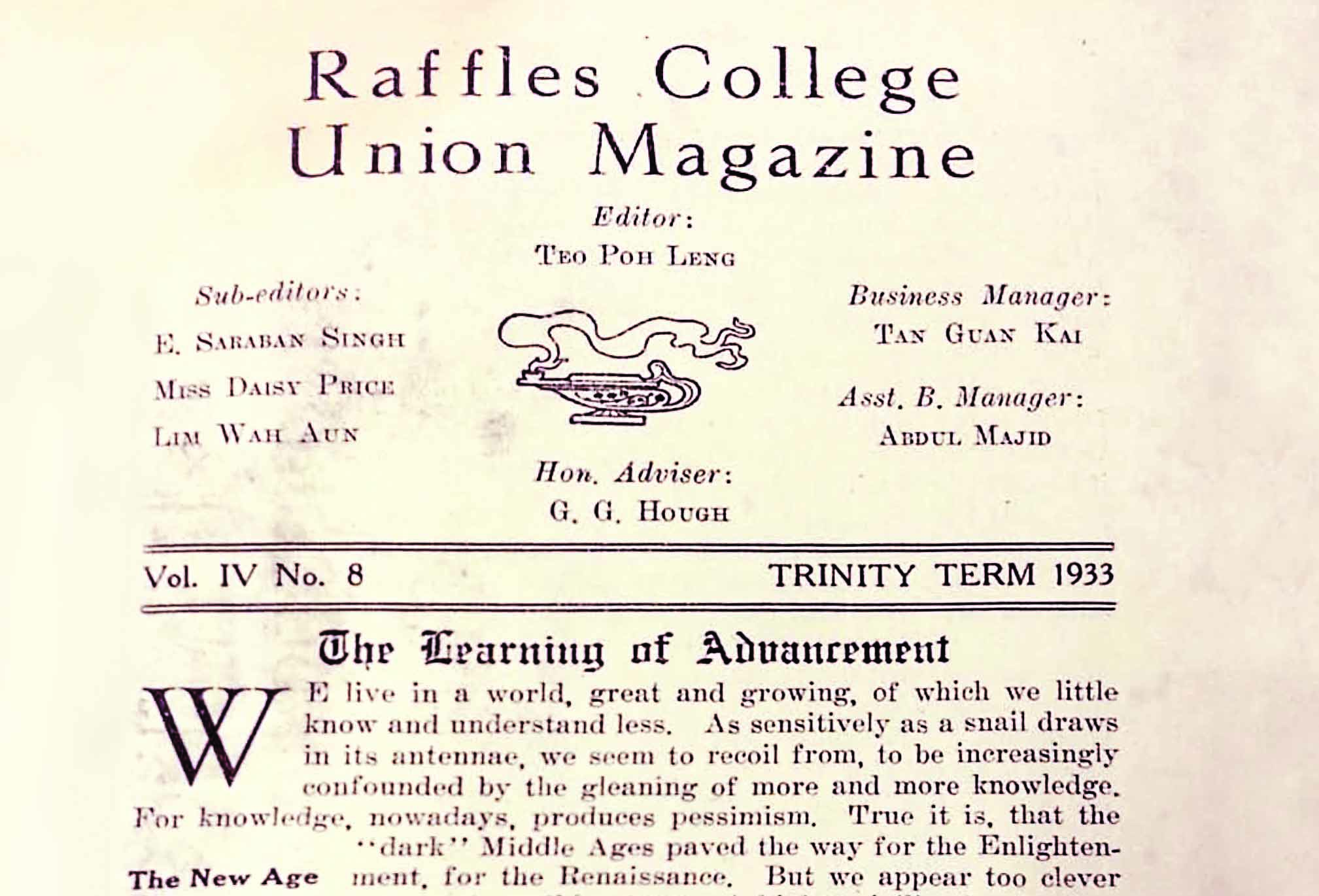

During his final year at Raffles College, as the editor of Raffles College Union Magazine, Teo encountered the Cornish poet Ronald Bottrall (1906–1989).17 In 1933, Bottrall had arrived in Singapore to become the Johore Professor at Raffles College, where he taught until 1937.18 The extensive overlaps between the literary texts Bottrall assigned to his students and the authors Teo discussed in the magazine suggest that Teo possibly attended Bottrall’s course.19 According to Rajeev S. Patke, Teo’s “Prolegomena to the Modern Poets” (1936), what he calls a rare up-to-date comprehensive sketch on modernist authors, indeed “owes something to Bottrall”.20 Teo’s admiration of Bottrall’s poems in the same essay suggests that Bottrall had also influenced him as a poet. Interestingly, considering that Bottrall’s complete name was Francis James Ronald Bottrall, it is possible that Teo’s pseudonym Francis P. Ng for his longest poem F.S.M.R. was his way of paying homage to his mentor.

It is highly likely that, upon graduation from Raffles College in 1934, Teo became a school teacher. No record of his school employment has been found but the Blue Book notes that he was a civil servant from 1934 to 1939.21 Chorus, the journal of the Singapore Teachers’ Association, affirms that, in 1938, Teo served on the subcommittee of the magazine together with Percival Frank Aroozoo (1900–1969), the former headmaster of Gan Eng Seng School and father of Mrs Hedwig Anuar (1938–), the first Singaporean director of the National Library of Singapore.22 Although publication of the Blue Book ceased in 1940 and hence provides no record of Teo’s status after 1939, it would be fair to speculate that he was a teacher at least until 1941. In the 1941 issue of Chorus I chanced upon Teo’s poem “The Spider”. 23

Raffles College Magazine, the publication of Raffles College, of which Teo Poh Leng was the editor in 1933. Teo also contributed articles to this magazine. Raffles College Union Magazine (1993, Trinity Term). (Vol. 4, No. 8), p. 1 Courtesy of NUS Central Library.

Raffles College Magazine, the publication of Raffles College, of which Teo Poh Leng was the editor in 1933. Teo also contributed articles to this magazine. Raffles College Union Magazine (1993, Trinity Term). (Vol. 4, No. 8), p. 1 Courtesy of NUS Central Library.

Oei Tiong Ham Hall at Rattles College, Bukit Timah Road, in 1938. Teo Poh Leng was a student at Raffles College from 1931 to 1934, where he trained to be a teacher. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Oei Tiong Ham Hall at Rattles College, Bukit Timah Road, in 1938. Teo Poh Leng was a student at Raffles College from 1931 to 1934, where he trained to be a teacher. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

A faded graduation photograph of the Raffles College batch of students in 1934. One of the students in this photo is Teo Poh Leng, but he remains unidentified as the author of this article has not been able track down anyone who can recognise him. Paul Abisheganaden is the eighth from the right in the middle row. Raffles College Union Magazine (1934 July). (Vol. 4, No. 10), insert between pp. 42 and 42. Courtesy of NUS Central Library.

A faded graduation photograph of the Raffles College batch of students in 1934. One of the students in this photo is Teo Poh Leng, but he remains unidentified as the author of this article has not been able track down anyone who can recognise him. Paul Abisheganaden is the eighth from the right in the middle row. Raffles College Union Magazine (1934 July). (Vol. 4, No. 10), insert between pp. 42 and 42. Courtesy of NUS Central Library.

Teo’s Vision For Malayan Modernism

Teo’s passion for poetry may have started during his years at SJI. At that time poetry was a popular genre taught at Anglophone schools from the primary level.24 Moreover, school magazines gave pupils an opportunity to write and publish their literary works. The old issues of St Joseph Magazine, for instance, contain literary works, although to a much lesser degree than The Rafflesian, the school magazine of Raffles Institution.

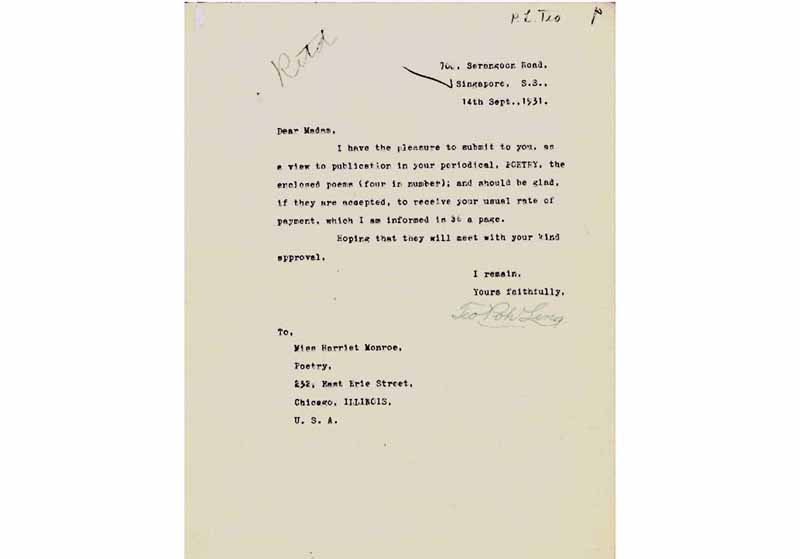

The earliest record of Teo’s poetry, however, dates from his first year at Rattles College. On 14 September 1931 from the address 700 Serangoon Road (presumably his home and currently a vacant plot of land in front of Kwong Wai Shiu Hospital), Teo mailed four poems to the American poet Harriet Monroe for publication in Poetry: The Magazine of Verse, although they went unpublished. 25 That was around one year before Teo started writing F.M.S.R.

Aside from F.M.S.R., its section titled “The Song of the Night Express” and the 1941 poem “The Spider”, Teo also wrote “Time is past” (1936).26 This poem appeared in The London Mercury, a major British literary magazine in the first half of the 20th century that published poems by Robert Frost and W.B. Yeats and was absorbed by Life and Letters To-day in 1939.

On 14 September 1931, in a letter addressed from 700 Serangoon Road (presumably his residence), Teo Poh Leng posted four poems to American poet Harriet Monroe for publication in Poetry: The Magazine of Verse. Unfortunately, his submissions were not accepted. Courtesy of the Special Collections Research Center, University of Chicago Library.

On 14 September 1931, in a letter addressed from 700 Serangoon Road (presumably his residence), Teo Poh Leng posted four poems to American poet Harriet Monroe for publication in Poetry: The Magazine of Verse. Unfortunately, his submissions were not accepted. Courtesy of the Special Collections Research Center, University of Chicago Library.

Section VII of F.M.S.R. retitled as "The Song of the Night Express" by Teo Poh Leng, was published in the 1937 spring issue of Life and Letters To-day, a British literary magazine. Life and To-day. (Vol. 16, No. 7)

Section VII of F.M.S.R. retitled as "The Song of the Night Express" by Teo Poh Leng, was published in the 1937 spring issue of Life and Letters To-day, a British literary magazine. Life and To-day. (Vol. 16, No. 7)

All these poems commonly engage with the theme of life’s journey. F.M.S.R., epitomised by “The Song of the Night Express”, is about a train ride and simultaneously the spiritual salvation of the self, with the travelling narrator aiming “to meet flesh of my flesh ’neath the station dome”27 once he reaches his destination. “Time is Past” is about the journey from birth to death. Starting with “Time was when life began,/ When Space was infinite”,28 the poem narrates one’s childhood, adulthood and afterlife in the light of Albert Einstein’s theory of relativity.29 “The Spider” approaches life as a repetitive circle, narrating a spider’s weaving of a web as an incessant repetition of creation and destruction.

What also unites these poems is their modernist outlook. The poems clearly carry the dark, pessimistic tones of the so-called “Lost Generation” authors who were disillusioned by the unprecedented mass destruction of World War I and became enamoured with the theme of the living dead. From “Singapura Lion-City”,30 F.M.S.R. laments, “The world is bad, / The world is mad, / The world is sad”.31 In “Time is Past”, the narrator seems to have entered the afterlife as “I move upon an earthless plane, / At last!” yet “perplexing and profound I seem” and this mental state is like “the ravine” which “makes me pale”.32 In “The Spider”, the narrator deplores his “deathless discipline” of continuously weaving a web only to be blown away as it “deadens me” and “I sigh”.33

Literary articles that Teo contributed to Raffles College Union Magazine during and after his college years demonstrate his distrust of contemporary society (yes, even back then) which he called “a wild beast”.34 Yet, Teo’s poetry was not about passively and helplessly shrinking in the face of this creature. Instead, it was an active response, participating in the “revolution of the arts”35 as led by T.S. Eliot and other modernist poets and artists. Teo both admired and absorbed their attempt to “seek new forms, new rhythms” in order to overcome “a moribund language” and “the fear [of the post-World War l era] that the language is dying”.36 The critical approach to contemporary society was part of this novelty: against the backdrop of conventional poetry represented by Percy Bysshe Shelly’s definition of poetry as “the record of the best and happiest moments of the happiest and best mind”,37 Teo called it a “great courage” on the part of modernist poets to try to “record the effects of the mighty march downward of civilisation, the collapse of culture, sometimes within the compass of less than 500 ‘tabloid’ lines”.38

Teo’s devotion to this modernist literary enterprise from the British colonial outpost in the tropics entailed a desire for the creation of Malayan art and culture. Lamenting Malaya for being “uncivilised in a cultural sense despite all her externals of civilised life”39 and believing in the ability of artists to “commenc[e] the original outlines” instead of merely “furnishing civilization”,40 Teo wrote poems with a strong vision for the advancement of what he would have called the Malayan civilisation at large. And significantly, central to this vision was an amalgamation of the East and West. While emulating Western modernist poets, Teo crafted into his poems the so-called Eastern view of life, seeing life’s journey as cyclic rather than linear, surmounting the notion of time, and picturing the encounter of various world and indigenous religions in the setting of the Lion City.

Tanjong Pagar Railway Station on Keppel Road in 1932. This is where trains from Malaysia arrived and departed from Singapore. Paul Yap Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Tanjong Pagar Railway Station on Keppel Road in 1932. This is where trains from Malaysia arrived and departed from Singapore. Paul Yap Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Disappearance During The Japanese Occupation

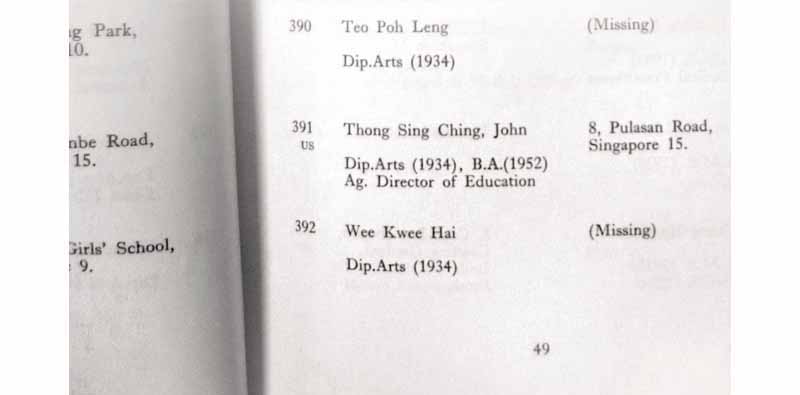

The publication of “The Spider” in 1941 is the last evidence of Teo’s life that I have been able to locate. His name does not appear in any later records and all leads from this point on have proved fruitless. The Register of Graduates (1963) reports Teo’s whereabouts as “missing”.41 The fact that Wee Kwee Hai, a schoolmate of his whose whereabouts is likewise listed as missing but who was later found to be killed during the Japanese Occupation, suggests that Teo may have met a similar fate – or possibly escaped Singapore. After all, as a member of the Straits Chinese British Association (now known as the Peranakan Association Singapore) and a pro-British school teacher having received an English education, he would have been a likely target of invading Japanese forces. 42

If so, how and when exactly did he perish during the Japanese Occupation? Was he massacred as part of the Sook Ching purge? Or did he share the same fate as Seow Poh Leng, his older colleague at the Straits Chinese British Association who died on a ship when it was bombed?43 Or did Teo survive the tumultuous year of 1942 only to end up either in Bahau, a newly created settlement for Eurasians and Chinese Catholics (where many perished from disease and malnutrition) or in Endau, a settlement for the Chinese led by Lim Boon Keng, a founding member of the Straits Chinese British Association?

Aside from all the known biographical details about Teo Poh Leng, I was particularly anxious during my visit to Singapore to find out if he had been dead for more than 70 years and if I could get in touch with members of his family. These two pieces of information would have facilitated not just publication of my analytical article, but more importantly, the reprint of F.M.S.R., reinstating its rightful place in the literary history of Singapore and allowing future generations to access this groundbreaking work.

But so far I have found neither evidence of his death nor record of his family. The incomplete Sook Ching victim list does not contain his name and neither do registers of cemeteries where Catholic Christians might have been buried.44 The Catholic Chancery Archives could not locate his death certificate either.45 At the National Archives of Singapore (NAS), I could not find Teo’s marriage register, which, if he were married, might have included his entire name signed in Chinese characters.

Old documents of the Straits Chinese British Association might have contained his biographical information, but even if that information existed, the association’s members would likely have burned them immediately after the Japanese bombing of Singapore on 8 December 1941, fearing that the Japanese might use the documents to target members.46 As for old materials stored at Raffles College, the Japanese army would have likely destroyed many records when the college was taken over.

I met or contacted siblings, children and grandchildren of people who knew Teo, hoping that someone would be able to shed light on the writer in his later years. I was especially hoping to hear something positive from the family of Paul Abisheganaden: Teo was well versed in Western classical music and Abisheganaden in literature, even becoming the secretary of the Literary Department of Raffles College at one point.47 Moreover, Teo’s Christian name was also Paul, suggesting that the two Pauls could have shared a common bond.48 Regrettably, Abisheganaden passed away in 2011 and his family has neither heard of Teo nor retained any of Abisheganaden’s private records that might have shed light on the elusive Teo. 49

Orphan Book Project

The death certificate and family records of Teo Poh Leng remain unknown. However, a month after my return to Germany from Singapore, I received a pleasant surprise from the United Kingdom Copyright Enquiries Service – namely, that the UK was to soon launch the Orphan Works Licensing Scheme. As of October 2014, it has become legal to republish an orphan book such as F.M.S.R. without permission from copyright holders on condition that a thorough search for its copyright owner has been conducted. 50

With this news, my laborious and slightly futile one-year search suddenly took on a glimmer of hope. I am now trying to complete my research and work towards republishing this neglected literary treasure. The reprinting of F.M.S.R. will fill the gap in Singapore’s literary past, and in particular, that of English-language literature – the genre which seems to have lagged behind Chinese-language and Malay-language works that have a more prolific history. Along with Lim Boon Keng’s Tragedies of Eastern Life (1927), F.M.S.R. will take its rightful place among pre-World War II 20th-century English literature from Singapore that Philip Holden, Rajeev S. Patke and John Clammer have analysed. F.M.S.R. will also serve as a bridge between post-World War II poetry pioneered by Edwin Thumboo (1933–) and the abundance of poems that poet Alvin Pang (1972–) is currently excavating from 19th-century Singapore school magazines.51

Teo Poh Leng listed as missing in The Register of Graduates (1968) belonging to the University of Malaya’s King Edward VII College of Medicine and Raffles College.

Teo Poh Leng listed as missing in The Register of Graduates (1968) belonging to the University of Malaya’s King Edward VII College of Medicine and Raffles College.

The National Library Board, Singapore holds two copies of F.M.S.R. which are kept at the Lee Kong Chian Reference Library on level 11 of the National Library. A microfilm copy shelved at NL 16347 is available for reference. Note: only four other libraries in the world hold copies of this book.

The writer would like to thank Ruth Chia, Joe Conceicao, Robbie Goh, Philip Holden, Koh Tai Ann, Catherine Lim, Janet Lim, Juliana Lim, Lim Su Min, Ng Ching Huei, Rajeev S. Patke, Valerie Siew, Peggy Tan, Edwin Thumboo, Medona Walter, Wang Gungwu, Richard Angus Whitehead and Ina Zhang Xing Hong – for their inputs in this project, and Harold Johnson for assisting her through the research process.

Dr Eriko Ogihara-Schuck, originally from Japan, is a lecturer in American Studies at the Technische Universität Dortmund, Germany. She is the author of Miyazaki s Animism Abroad: The Reception of Japanese Religious Themes by American and German Audiences (2014). Motivated by her research on Francis P. Ng, she is launching a larger project on Singapore-US relations in the area of literature and popular culture.

REFERENCES

Clammer, J.B. (1980). Straits Chinese society: Studies in the sociology of the Baba communities of Malaysia and Singapore. Singapore: NUS Press. (Call no.: RSING 301.45195105957 CLA)

Eliot, T. (2003). The waste land and other poems. Longman: Penguin Books. (Not available in NLB holdings)

Ng, F.P. (1937). F.M.S.R.: A poem. London: Author H Stockwell. (Call no.: RRARE 821.9 PNG; Microfilm no.: NL16347)

Patke, R.S., & Holden, P. (2010). The Routledge concise history of Southeast Asian writing in English. New York: Routledge. (Call no.: RSING 895.9 PAT)

Poon, A., & Holden, P., & Lim, S. G-L. (2009). (Eds.). Writing Singapore: An historical anthology of Singapore literature. Singapore: NUS Press. (Call no.: RSING S820.8 WRI)

Teo. P.L. (1933, Hilary Term). The learning of advancement. Raffles College Magazine, 3 (7), 4.

Teo, P.L. (1936, Trinity Term). Prolegomena to the modern poets. Raffles College Magazine, 6 (1), 14.

Teo, P.L. (1937, Spring). The song of the night express. Life and Letters To-Day, 16 (7), 44.

Teo, P.L. (1941, November). The spider. Chorus: The Journal of the Singapore Teacher’s Association, , 7, 53.

Teo, P.L. (1936, January). Time is past. The London Mercury, 33 (95), 275.

NOTES

-

The book actually does not indicate this publication date; it only says that Ng completed the poem between 1932 and 1934 and the preface in 1935 (“Note”). Publication of advertisements and reviews begins in 1937, suggesting that the book was published in that year. See Poetry review supplement. (1937). Poetry review, 28, xi; As I was saying. (1937, December 18). The Singapore Free press, p. 8: Notes of the day: Modern. (1937, December 21). The Straits Times, p. 12. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Singaporean literature. (2020, October 13). Wikipedia. Retrieved from Wikipedia website. ↩

-

Patke, R.S., & Holden, P. (2010). The Routledge concise history of Southeast Asian writing in English (p. 47). New York: Routledge. (Call no.: RSING 895.9 PAT) ↩

-

Poon, A., & Holden, P., & Lim, S. G-L. (2009). (Eds.). Introduction: Literature in English in Singapore before 1965. In Writing Singapore: An historical anthology of Singapore literature (p. 10). Singapore: NUS Press. (Call no.: RSING S820.8 WRI) ↩

-

According to WorldCat, F.M.S.R. is also available at the British Library, the National Library of Scotland, the Oxford University Library and the University of North Carolina Library. ↩

-

Arthur H Stockwell Ltd. (2003, July 9). Email to the Author. ↩

-

Ng, F.P. (1937). F.M.S.R.: A poem (p. 18). London: Author H Stockwell. (Call no.: RRARE 821.9 PNG; Microfilm no.: NL16347) ↩

-

Teo, P.L. (1939, Spring). The song of the night express. Life and Letters To-Day, 16 (7), 44. ↩

-

Notes on contributors. (1937, Spring). Life and Letters To-Day, 16 (7), ix. ↩

-

Archives of the Roman Catholis Archdiocese of Singapore. (2014, September 16). Email to the Author. At the Catholic Young Men’s Association, Teo Poh Leng was elected to the Vice President in 1932 and was the Honorary Librarian from 1935–1937. In 1934 he was also elected to be a special correspondent of the Malaya Catholic Leader. See Catholic Young Men’s Association of Singapore. (1935, March 2). Malaya Catholic Leader, 1 (9), 19; Untitled. (1932, September 9). The Straits Times, p. 12; C.Y.M.A.: Church of St. Peter and Paul (Singapore). (1935, March 9). Malaya Catholic Leader, 1 (10), 16; Catholic Young Men’s Association: The study class. (1936, October 3). Malaya Catholic Leader, 13; Catholic Young Men’s Association. (1936, November 28). Malaya Catholic Leader, 13; Church of SS Peter and Paul: Catholic Young Men’s Association. (1937, February 6). Malaya Catholic Leader, 18; Church of SS. Peter & Paul. (1937, February 13). Malaya Catholic Leader, 19. ↩

-

Examination results. (1930). St Joseph’s Magazine: Chronicle, 29. ↩

-

University of Cambridge local examinations syndicate: Junior local examination, December 1928. University of Cambridge local examinations syndicate: School certificate examination, December 1929: Detailed report. These sources were provided by SJI Archives. ↩

-

St Joseph’s Magazine: Chronicle, 1930, 29. ↩

-

1931.(1993). Raffles College 1928–1949. Singapore: Alumni Affairs and Development Office. (Call no.: RSING 378.5957 RAF). According to the Straits Settlements blue book for 1934–1939, Teo joined the civil service on February 14, 1929. His name was however not found in the establishment list for the education service for the years 1929–1933 in the Straits Settlements blue book. See Fuan, T.Y. (2013, October 28). Teo Poh Leng. Email to the Author. ↩

-

Raffles College 1928–1949, 1993; Fuan, 28 Oct 2013. ↩

-

Union notes: Magazine Committee. (1933). Raffles College Magazine, 3 (7), 62. ↩

-

Bottrall arrived in Singapore on December 8, 1933 and resigned the Johore Professor of Raffles College on October 2, 1937. See College notes. (1934, February). Raffles College Magazine, 4 (9), 48; College chronicle. (1938). Raffles College Magazine, 8 (1), 63. ↩

-

English language and literature. (1935). Raffles College Singapore: Calendar 1935–1936 (pp. 12–14). Singapore: Malaya Publishing House. (Not available in NLB holdings) ↩

-

Patke, R.S. (2009, December). Canons and questions of value in literature in english from the Malayan Peninsula. Asiatic, 3 (2), 44. ↩

-

See Fuan, 28 Oct 2013. ↩

-

The Singapore Teachers’ Association: Office-bearers for the year 1938. (1938, September). Chorus: The Journal of the Singapore Teachers’ Association, 4, 90. ↩

-

Teo, P.L. (1941, November). The spider. Chorus: The Journal of the Singapore Teacher’s Association, 7, 90. ↩

-

Chua, J.C.H. (Interviewer). (1993, March 9). Oral history interview with Paul Abisheganaden. Transcript of recording no. 001415/48/02, p. 22. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

Teo, P.L. (1931, September 14). Letter to Harriet Monroe, Poetry. Guide to the poetry: A magazine of verse records 1895–1961. Administrative files, series 1, box 25, folder 11. The special collections research center, University of Chicago. ↩

-

Teo, P.L. (1936, January). Time is past. The London Mercury, 33 (195), 275. ↩

-

The London Mercury, Jan 1936, p. 275. ↩

-

Teo. P.L. (1933, Hilary Term). The learning of advancement. Raffles College Magazine, 3 (7), 4. ↩

-

The London Mercury, Jan 1936, p. 275. ↩

-

Chorus: The Journal of the Singapore Teacher’s Association, Nov 1941, p. 53. ↩

-

Raffles College Magazine, Hilary Term, 1933, 3 (7), 4. ↩

-

Raffles College Magazine, Hilary Term, 1933, 3 (7), 5. ↩

-

Teo, P.L. (1936, Trinity Term). Prolegomena to the modern poets. Raffles College Magazine, 6 (1), 14. ↩

-

Raffles College Magazine, Trinity Term, 1936, 6 (1), 15. ↩

-

Raffles College Magazine, Trinity Term, 1936, 6 (1), 19. ↩

-

Raffles College Magazine, Hilary Term, 1933, 3 (7), 5. ↩

-

Raffles College Magazine, Hilary Term, 1933, 3 (7), 6. ↩

-

University of Malaya. (1963). The register of graduates (p. 49). Singapore: University of Malaya. (Call no.: RCLOS 378.595 UM) ↩

-

In 1934, Seow Poh Leng was also elected to be a messenger of the Straits Chinese British Association. See Straits Chinese and Education Policy: New officers. (1934, November 9). The Straits Times, p. 12. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Lim, S.M. (2014, November 2). Email to the author. In 1924, Teo and Seow Poh Leng were both elected to be messengers of the Straits Chinese British Association. See The Straits Times, 9 Nov 1934, p. 12. ↩

-

許雲樵、蔡史君編. 新馬華人抗日史料: 1937–1945. 新加坡文史出版 1984.pp. 999–1000. ↩

-

Archives of the Chancery of the Roman Catholic Archidiocese of Singapore. (2014, September 16). Email to the Author. ↩

-

How S.C.B.A. was revived after the war. (1950). S.C.B.A. Golden Jubilee Souvenir: 1900–1950 (p. 28). Singapore: S.C.B.A. Golden Jubilee Brochure Sub-Committee. (Not available in NLB holdings) ↩

-

Literary Department. Report for Hilary Term 1934. (1934, July). Raffles College Union Magazine, 4 (10), 45. As for Teo’s interest in the intersection of poetry and music, see Teo, P.L. (1939, Trinity Term). Poetry and music - I. Raffles College Union Magazine, 9 (1), pp. 4–13; Teo, P.L. (1940–1941). Poetry and music – II. Raffles College Union Magazine, 10, pp. 5–15. ↩

-

Local examination results. (1930, April 9). The Singapore Free Press, p. 12. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Abisheganaden, A., & Abisheganaden, J. (2014, August 15). Inteview with the Author; Chia, R. (2014, August 29). Email to the Author. ↩

-

United Kingdom Copyright Enquiries Service. (2014, September 22). Email to the Author. ↩

-

While I was in Singapore, Alvin Pang shared with me an interesting anecdote about his thrilling encounter with F.M.S.R. Some years before the book was introduced in a Wikipedia entry on Singapore literature in 2005, Yenping Yeo, a former NL Librarian who was tidying up NL’s old collection in the closed stacks, found the book and showed it to him. ↩