The National Library's Rare Maps Collection

The National Library has a collection of rare maps dating back to the 15th century. Makeswary Periasamy shares the significance and history of these maps and their makers.

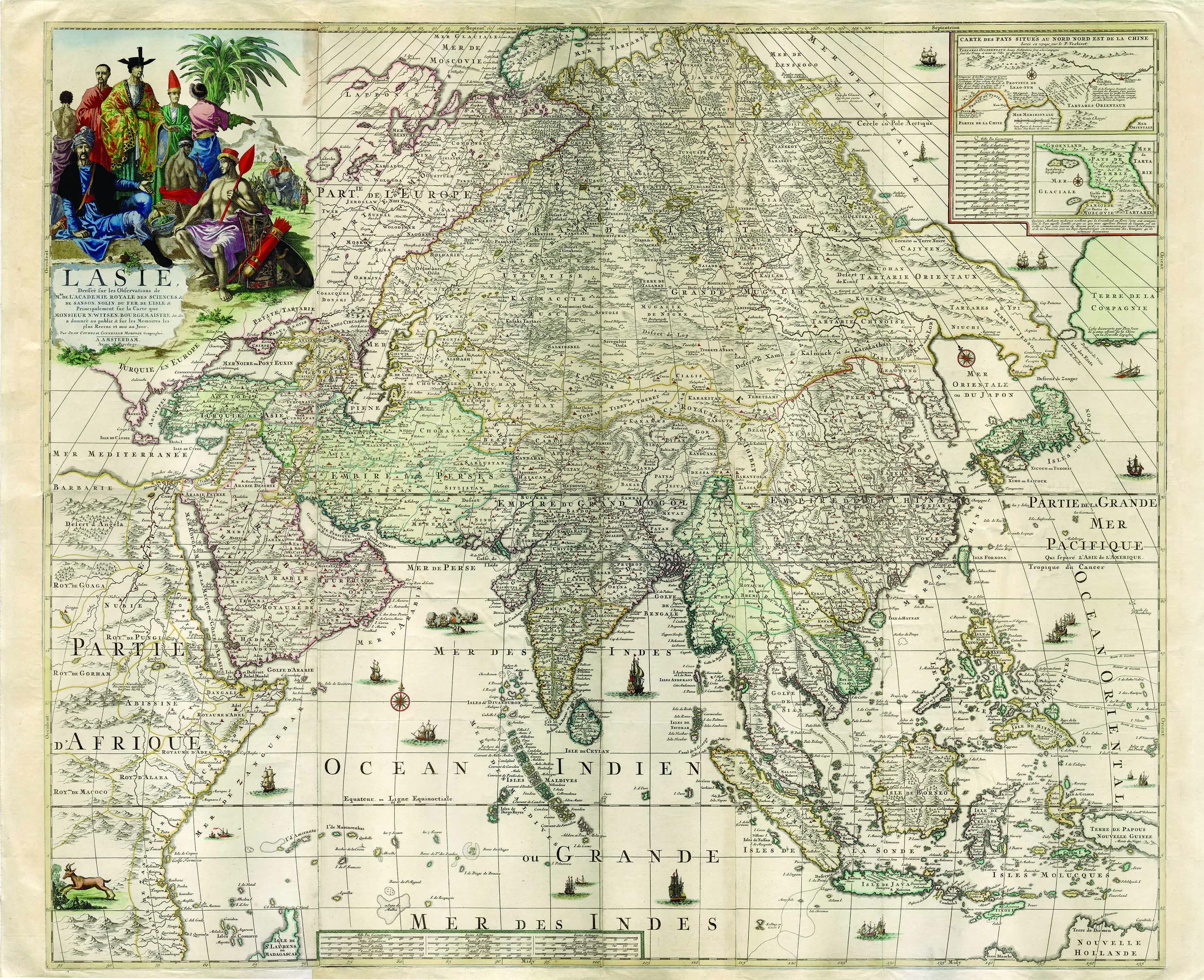

Detail from a wall map by map printing and publishing firm Covens & Mortier. L’Asie dressée sur les observations de M.rs de l’Académie Royale de Sciences & de Sanson, Nolin, Du Fer, De L’Isle & principalement sur la carte que monsieur N: Witsen Bourgemaistre &c. &c. a donneé au public & sur les memoires les plus recens et mis au jour, Johannes Covens and Cornelis Mortier (Amsterdam, circa 1730).

Detail from a wall map by map printing and publishing firm Covens & Mortier. L’Asie dressée sur les observations de M.rs de l’Académie Royale de Sciences & de Sanson, Nolin, Du Fer, De L’Isle & principalement sur la carte que monsieur N: Witsen Bourgemaistre &c. &c. a donneé au public & sur les memoires les plus recens et mis au jour, Johannes Covens and Cornelis Mortier (Amsterdam, circa 1730).The National Library’s Rare Maps Collection forms part of the valuable Rare Materials Collection held in its Lee Kong Chian Reference Library. The collection contains topographic maps and navigational charts covering Singapore, Southeast Asia and Asia, as well as town plans and street maps of Singapore and Malaya. The majority of the maps were printed by European map-makers before 1945.

Most of the maps were inherited from the former Raffles Museum and Library, in particular a set of early Malayan maps photocopied by J.V. Mills in 1936, now known as the Mills Collection, which comprises 208 maps and charts relating to the Malay Peninsula from the period before 1600 until 1879. Other maps were donated to the library and the rest were purchased over the years. In 2012, the library acquired the valuable and historically significant David Parry Southeast Asian Map Collection, which constitutes 254 maps dating from the 15th to 19th centuries and created by prominent European cartographers.

The Rare Maps Collection includes maps that illustrate the development of European mapping of early Southeast Asia, as well as the history of the region. These early maps and charts were produced during the “age of discovery” when Europeans were looking for a sea route to Asia and the famed Spice Islands (Moluccas, today known as Maluku) of Indonesia, in the hope of securing the lucrative trade in spices such as pepper, cloves and nutmeg.

The Portuguese were the first Europeans to discover a sea route to Asia in the late 15th century when the intrepid explorer Vasco da Gama reached India in 1498. The Spanish followed suit not long after and managed to sail to Asia in the early 16th century. Having found a safe route to Asia, the Iberian powers began to explore the region, in the process mapping the surrounding lands as well as charting its waters.

The first printed maps of Southeast Asia, however, were produced by Italian and German map-makers from the late 1470s onwards – even before the Portuguese and Spanish arrived in the region. These early maps were based on Claudius Ptolemy’s Geography, the 2nd-century Greek astronomer’s work that contained precise instructions on mapping the world. The textual instructions in Geography contained several fundamental errors but nevertheless continued to influence map-making for centuries despite newer discoveries.

Italy and Germany played important roles in map production at the start of the Renaissance period, particularly Italy, whose coastal cities served as the midpoint between the trade routes of Europe and Asia.1 However, map-making in Italy languished at the start of the 1500s (unlike in central Europe), until it was revived by the leading Italian geographer Giacoma Gastaldi in the mid-1500s. Map-making subsequently declined again in the 1800s.2

The period from 1570 to 1670 was known as the golden age of cartography and the Dutch were the leading map-makers of this era.3 Notable Dutch cartographers during this period include Gerard Mercator, Abraham Ortelius, Willem Janszoon Blaeu and Jodocus Hondius.

Although Germany did not dominate map-making for an entire era, unlike the other European countries, German map-makers made important contributions to map-making from the 15th to 18th centuries. With the advances in printing technology in the 16th century, Germany (where the printing press was invented) became an important centre for map-making, far surpassing Italy. German map-makers also created better tools for map surveying. German map-making declined in the 17th century when Dutch map-makers became more prominent, but when the latter slowed down in the 18th century, German map-makers became active again. 4

The French and English were not as active in map-making as the Italians, Germans or Dutch, although they did produce some fine maps of their own. The English started producing better quality and more accurate maps in the 18th and 19th centuries. Two of the key maps on the Singapore and Malacca Straits in the Rare Maps Collection were produced by French and English map-makers.

By the start of the 17th century, Paris had become an important secondary publishing centre, rivalling those in the Netherlands, namely Antwerp and Amsterdam. Many atlases were co-published by the Dutch and French, and Dutch atlases began to be issued with French text.5 The development of cartography in the Netherlands had a direct impact on map-making in Germany and France, with the map-makers from the three countries often collaborating with one another.6

Despite being the first Europeans to go on explorations, the Portuguese and Spanish did not play a significant role in the development of printed cartography. They carefully guarded their maps and charts, as well as the information collected during their voyages of discovery, particularly the sailing routes to the key trading ports in Asia. However, their manuscript charts “remained the sole cartographical source for the New World and the East Indies” and was the basis for many of the maps created by the other European cartographers during the 16th century.7 The other Europeans managed to smuggle the information out from these secret archives and began printing maps of Southeast Asia based on the new discoveries.

The National Library’s collection of rare maps is an important source for the study of early cartography of the region, as well as the development of European mapping of Southeast Asia, a region whose early European names included East Indies, Indiae Orientalis, East Indian Islands and Further India (India Extrema). These maps are also useful for those researching early Malayan cartography as they contain some of the earliest references to Singapore and the Malay Peninsula.

GIACOMO GASTALDI

Giacomo Gastaldi (circa 1500–65) was a Venetian cartographer, astronomer and engineer who was considered one of the most important cartographers of his time. He reintroduced copper engraving for maps, hence creating more detailed maps in the process. Prior to this, maps were printed from woodcuts. His world map, printed in 1546, names the southern portion of the Malay Peninsula as “C. Cin Copula”, an early, albeit, incorrect reference to Singapore as a cape.

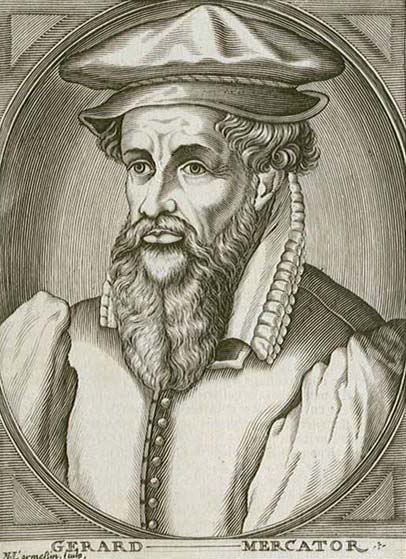

Portrait engraving of Dutch cartographer Gerard Mercator, circa 1739. Wikimedia Commons.

Portrait engraving of Dutch cartographer Gerard Mercator, circa 1739. Wikimedia Commons.

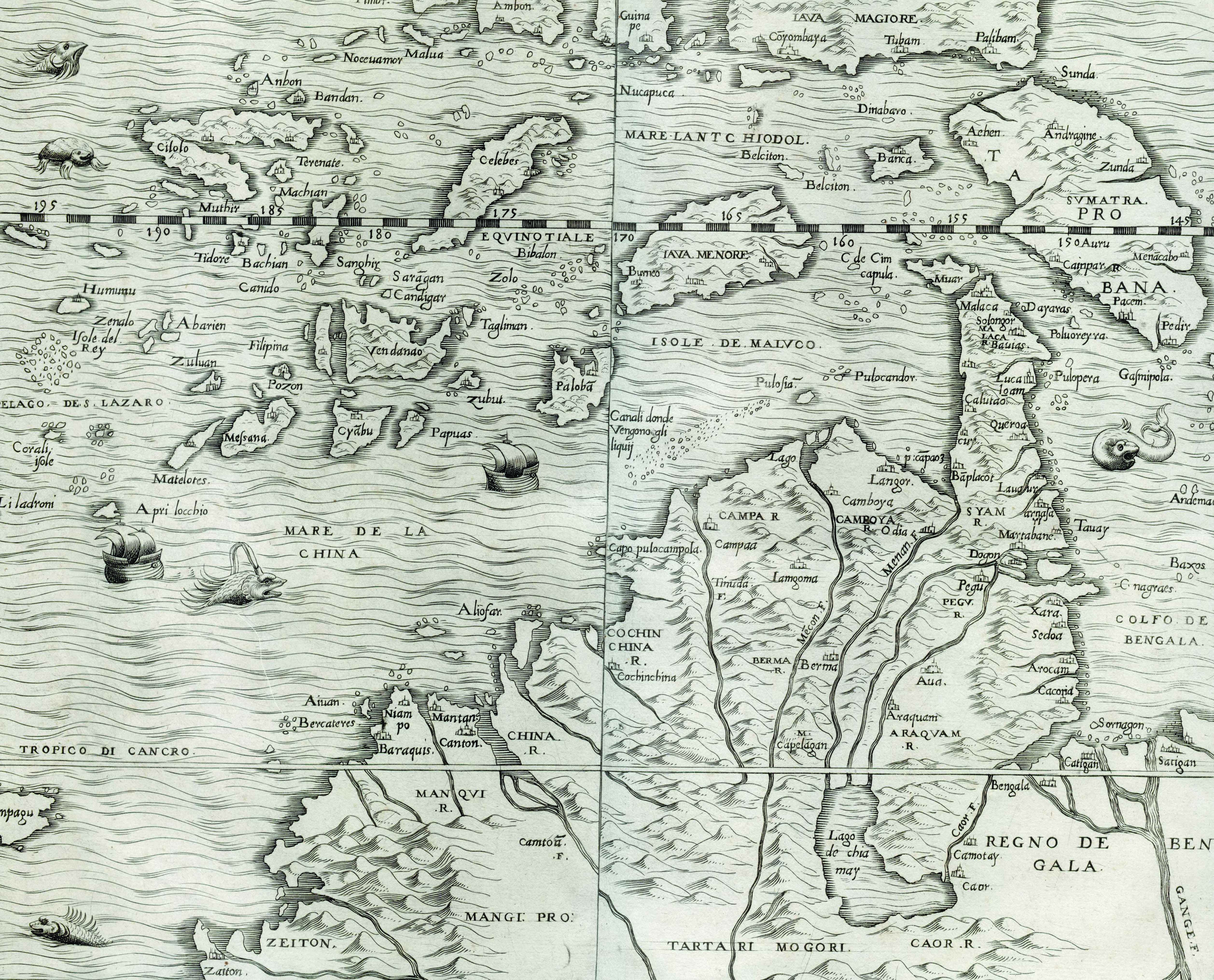

Gastaldi’s later Southeast Asian map, Terza Tavola, again refers to Singapore as a cape (C. de cim capula). The Malay Peninsula is slanted towards the east, with its lower tip (Muar) separated from the mainland. The map, with no title but simply called the “third map” (or “Terza Tavola”), was printed in Giovanni Battista Ramusio’s collection of voyages and travels.8

Although an improvement from previous Ptolemaic maps, Gastaldi still refers to Sumatra and Borneo by their Ptolemaic names of Taprobana and Java Menore.

Terza Tavola, Giacomo Gastaldi for Giovanni Battista Ramusio (Venice, circa 1563). Note: the map is oriented with the south at the top.

Terza Tavola, Giacomo Gastaldi for Giovanni Battista Ramusio (Venice, circa 1563). Note: the map is oriented with the south at the top.

ABRAHAM ORTELIUS

Abraham Ortelius (1527–98), a leading Flemish cartographer, was a map dealer and publisher. During the 1560s, he collected maps and details of their sources and commissioned new printing plates for them. His 1570 atlas, the Theatrum Orbis Terrarum (Theatre of the World), was hailed as the first comprehensive, modern atlas of the world in which all the maps were of uniform size and format.9

Portrait of Abraham Ortelius by Peter Paul Rubens. Wikimedia Commons

Portrait of Abraham Ortelius by Peter Paul Rubens. Wikimedia Commons

Ortelius’ map features Southeast Asia, Japan, the Philippines and part of the west coast of America. The map also features the Indonesian Spice Islands, with accompanying text that describes the spices produced. Despite European explorations in the region, Ortelius’ map contains a few inaccuracies: Sumatra and Java are depicted as being much larger than they actually are while the Philippines is featured without its northern island of Luzon. Singapore (Cincapura) is identified as a town on the promontory of the Malay Peninsula.

Below Java, at the southern end of the map, a part of Terra Australis Incognita is evident. Labelled as pars continentis Australis, its northern tip is called Beach, due to 16th-century map-makers misreading Marco Polo’s description of Locach, a southern kingdom thought to be filled with gold that he wrongly located below Java. Based on early records, Beach or Locach was probably the name of a place in Cambodia. 10

First produced in 1570, Ortelius’ atlas was reprinted in various European languages.

Indiae orientalis, insularumque adiacientium typus, Abraham Ortelius (Antwerp, 1579)

Indiae orientalis, insularumque adiacientium typus, Abraham Ortelius (Antwerp, 1579)

THEODORE DE BRY

Theodore de Bry (1528–98) was a Flemish engraver, illustrator, printmaker and publisher who was trained as a goldsmith and engraver. De Bry created many fine engravings to illustrate travel books and published several illustrated works (originally in Latin but later translated into German, English and French) that were a useful reference for Europeans about the Americas and the new places they depicted.11

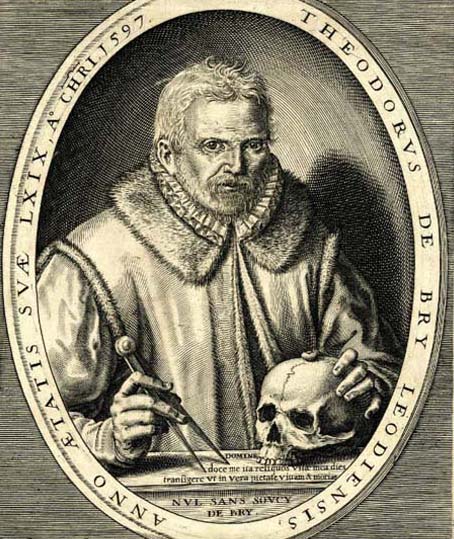

A portrait of Theodore de Bry. Wikimedia Commons.

A portrait of Theodore de Bry. Wikimedia Commons.

He is famous for compiling a well-illustrated collection of voyages and travels to the East and West Indies, which were categorised into two distinct series: the Grands Voyages, which started in 1590 and covered America, and the Petits Voyages, which began in 1598 and covered Asia and Africa.12

De Bry’s map is based on Willem Lodewijcksz’s 1598 map. Lodewijcksz was part of the first Dutch voyage to Southeast Asia under the command of Cornelis de Houtman from 1595 to 1597. Lodewijcksz’s map charted the Southeast Asian region in detail, including the Malacca and Sunda Straits, and was one of the first maps to focus on the areas around the Malay Peninsula.13

While the Malay Peninsula is called Chersonese Aurea, an old Ptolemaic name depicting it as a land of gold, Singapore is once again erroneously identified as a cape at the eastern end of the peninsula. The map also features the northern coast of Java in greater detail.

Interestingly, the map depicts a trans-peninsular waterway bisecting the Malay Peninsula at its southern tip. This river channel with the Muar River at the western end and the Pahang River at the eastern end was used as an overland trade route. Several maps from the 16th century to the second decade of the 17th century also contain this unique feature. De Bry’s map clearly marks the rivers on each side as R. Farmeso and Muar R.

Lodewijcksz’s map was suppressed by Dutch merchants who did not wish to reveal the sailing routes to the lucrative ports of Southeast Asia. But it was published later in the same year by de Bry in Petits Voyages.14

Nova tabula insularum Iavae, Sumatrae, Borneonis et aliarum Malaccam usque, delineata in insula Iava, ubi ad vivum designantur vada et brevia scopulique interjacentes descripta l G.M.A.L., Theodore de Bry, after Willem Lodewijcksz (Frankfurt, 1598).

Nova tabula insularum Iavae, Sumatrae, Borneonis et aliarum Malaccam usque, delineata in insula Iava, ubi ad vivum designantur vada et brevia scopulique interjacentes descripta l G.M.A.L., Theodore de Bry, after Willem Lodewijcksz (Frankfurt, 1598).

SEBASTIAN MÜNSTER

Sebastian Münster (1489–1552) was a German Professor of Hebrew, a famous mathematician, geographer and a leading map-maker. He is usually regarded as the most important map-maker of the 16th century.

Portrait of Sebastian Münster by Christoph Amberger, c. 1552. Wikimedia Commons.

Portrait of Sebastian Münster by Christoph Amberger, c. 1552. Wikimedia Commons.

Münster was widely known for Cosmographia, first published in 1544, which features several woodcut maps illustrated with vignettes and fanciful creatures.15 He was also the first to introduce a separate map for each of the four continents – Europe, Africa, Asia and America – known then.16

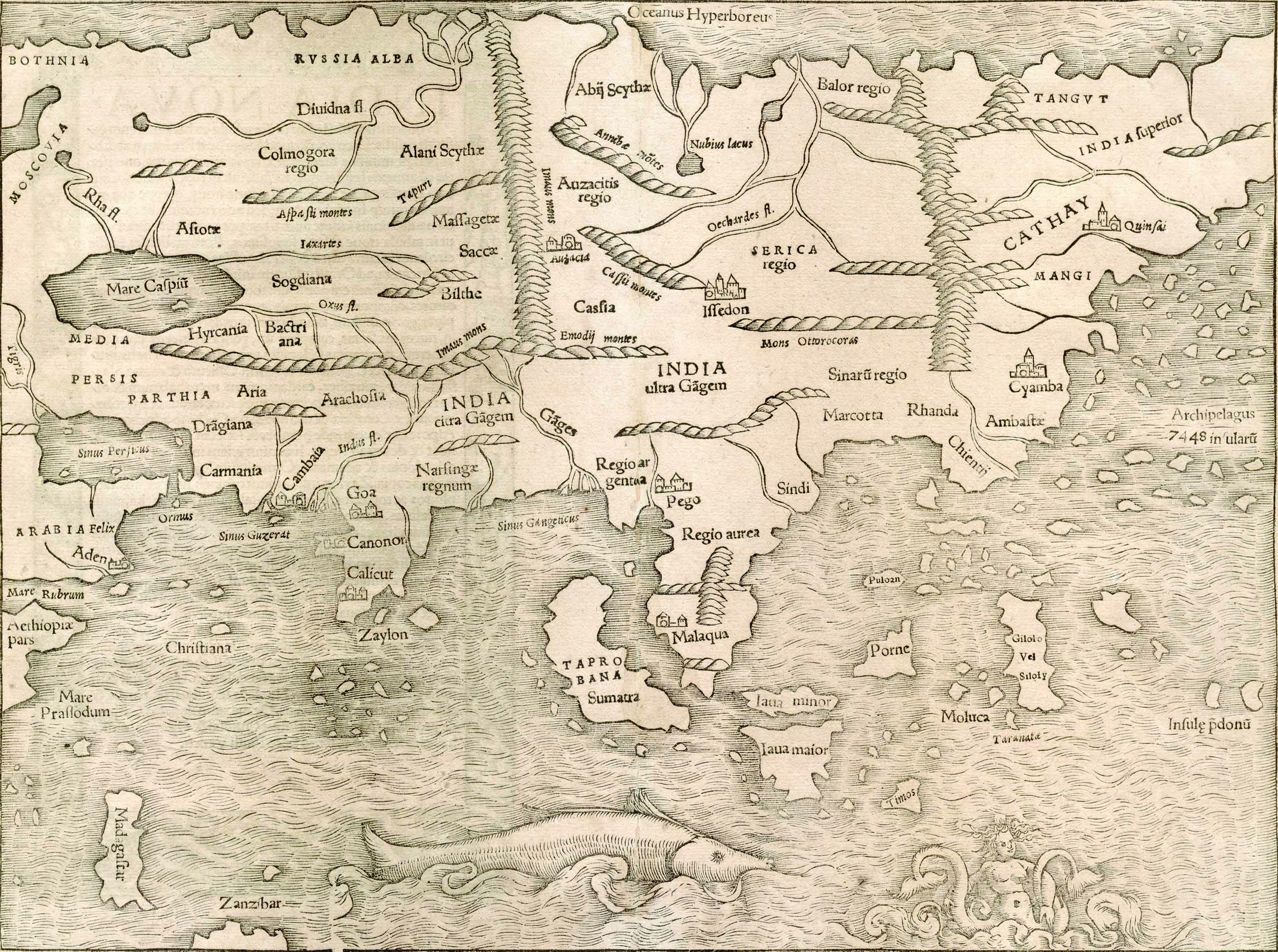

This map was published in Münster’s 1540 Geographia Universalis, which was based on Ptolemy’s seminal work Geography but also incorporated new discoveries. Here, unlike earlier maps, Asia is depicted separately from Southeast Asia and the Moluccas (Maluku) is drawn correctly at the west coast of Halmahera. Sumatra is called by both its modern name and its Ptolemaic name of Taprohana.

The shape of the Malay Peninsula is much improved, with only the city of Malaqua (Malacca) named.17 Until the 17th century, most maps named the southern part of the Peninsula as Malacca, an “exaggeration of the real extent of European influence and control”.18 Malacca was strategically located in the middle of important sea routes and the Portuguese took control of it in 1511. By the end of 1500s, Malacca had become one of the key trading ports of the world.19 Notably, there was no incentive to map the remaining interior of the Malay Peninsula.

India Extrema XIX nova tabula by Sebastian Münster (Basle, 1540).

India Extrema XIX nova tabula by Sebastian Münster (Basle, 1540).

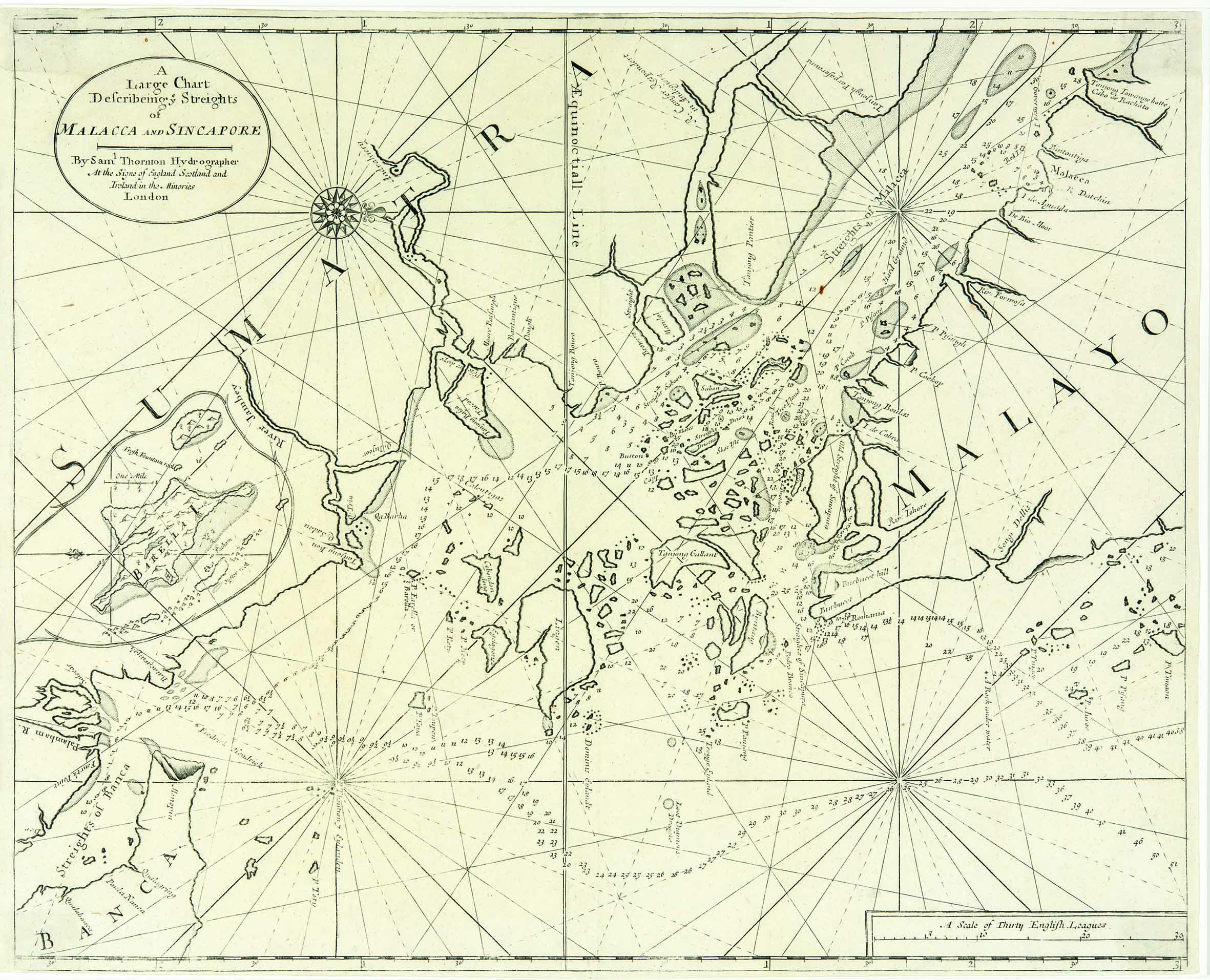

SAMUEL THORNTON

Samuel Thornton (fl. 1703–39) was an English hydrographer.20 His father, John Thornton was the official hydrographer to the British East India Company in the 17th century who collaborated with John Seller to produce the first English sea atlas, The English Pilot. The Pilot was to be produced as four parts, with The Third Book concentrating on “Oriental navigation”. Eventually titled as Oriental Navigation, this book was subsequently completed by John Thornton’s son (who shared the same name) in 1703.21

Portrait of Samuel Thornton by Karl Anton Hickel. Collection of Bank of England.

Portrait of Samuel Thornton by Karl Anton Hickel. Collection of Bank of England.

Samuel Thornton took over his brother’s business in 1706 and re-issued the charts under his own name. The chart below is from Samuel Thornton’s re-issue of Oriental Navigation, which describes the passage through the Singapore Strait clearly. The chart identifies the island of Singapore as the Old Streights of Sincapura, an indication that the name Singapore or its variant terms in early European sources were more often a reference to the sea passage rather than to the island or city.

European maps and charts of the 16th and 17th centuries tended to call Singapore by various names and depicted it either as a port, or city, an island, one of the four straits, a cape or promontory, or as the entire southern portion of the Malay Peninsula. 22

Thornton’s chart, oriented with north to the right, is one of the first English charts of Southeast Asia. The map, stretching from the Malacca Strait through the Singapore Strait to the Banka Strait indicates the principal sea routes as well as the soundings (sea depths) of the region.

A large chart describing ye Streights of Malacca and Sincapore, Samuel Thornton (London, circa 1711).

A large chart describing ye Streights of Malacca and Sincapore, Samuel Thornton (London, circa 1711).

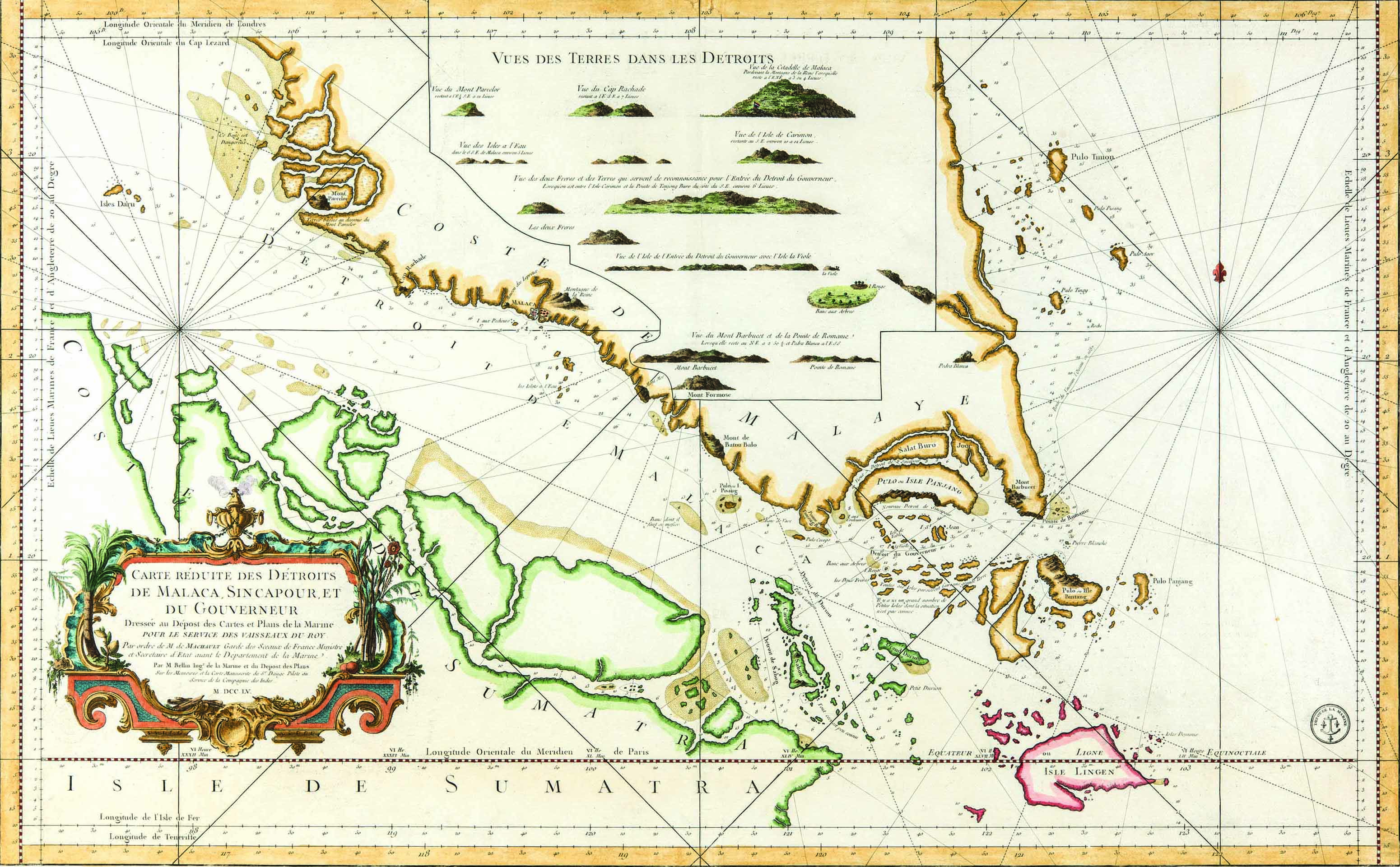

JACQUES NOCOLAS BELLIN

Jacques Nicolas Bellin (1703–72) was a French royal hydrographer who created maps for several key publications in the 18th century, such as Prévost’s L’Histoire Générale des Voyages (1747–61) and Petit Atlas Maritime (1764) . His son (1745–85), who went by the same name, was an engraver based in Paris.23

The Singapore Straits that connected the Indian Ocean to the South China Sea was an important trade route. What was collectively referred to as the Singapore Straits was actually four maritime arteries (namely the Old Strait, New Strait, Governor’s Strait and the Johor Strait) that were often called by various names and mistaken for one another.

One of the maps in the collection that perpetuates this confusion is Bellin’s map, which depicts the Johor Strait as the Old Strait of Singapore (Vieux Detroit de Sincapour). The Johor Strait (Selat Tubrau in Portuguese or Selat Tebrau in Malay) refers to the narrow channel between the Malay Peninsula and Singapore. It was often marked as the “Old Strait of Singapore” in late 17th and 18th century maps. Strangely, Bellin’s map shows two islands in the Johor Strait – Salat Buro and Joor. Johor Strait was also known as Salatburo or Salat Tubro.

Bellin’s map recommends the sea passage through the Singapore Strait for vessels that could sail through the Old Strait and return via the New Strait. However, Bellin’s map erroneously identifies the Old Strait as “Nouveau Detroit de Sincapour” (New Strait of Singapore) and the New Strait as “Detroit du Gouverneu” (Governor’s Strait).

Bellin’s map depicts Singapore island in an unrecognisable shape and calls it “Pulo ou Isle Panjang”, one of the early names used for the island. The map also features coastal profiles at its centre.

Carte réduite des détroits de Malaca, Sincapour, et du Gouverneur dressée au dépost des cartes et plans de la marine, Jacques Nicolas Bellin (Paris, 1755).

Carte réduite des détroits de Malaca, Sincapour, et du Gouverneur dressée au dépost des cartes et plans de la marine, Jacques Nicolas Bellin (Paris, 1755).

COVENS & MORTIER

Covens & Mortier was a successful map printing and publishing firm in Amsterdam, based on the successful business started by Cornelis Mortier’s father, Pierre Mortier, in Paris in the late 17th century. The firm re-issued the maps of several European map-makers until its closure in 1866.24

This wall map shows the trade route from Siam to Batavia and then to Europe through the Sunda Straits. By the mid-17th century, the Dutch East India Company had established a trading post in Siam. This map has illustrations of ships, animals and an elaborate title cartouche that features the various natives of Asia. Maps in the 18th century, besides being a source of geographical information, were also becoming important as collectors’ items. Hence, the use of decorative features was more prominent during this time.

L’Asie dressée sur les observations de M.rs de l’Académie Royale de Sciences & de Sanson, Nolin, Du Fer, De L’Isle & principalement sur la carte que monsieur N: Witsen Bourgemaistre &c. &c. a donneé au public & sur les memoires les plus recens et mis au jour, Johannes Covens and Cornelis Mortier (Amsterdam, circa 1730).

L’Asie dressée sur les observations de M.rs de l’Académie Royale de Sciences & de Sanson, Nolin, Du Fer, De L’Isle & principalement sur la carte que monsieur N: Witsen Bourgemaistre &c. &c. a donneé au public & sur les memoires les plus recens et mis au jour, Johannes Covens and Cornelis Mortier (Amsterdam, circa 1730).

Makeswary Periasamy is a Senior Librarian with the National Library of Singapore. She selects and acquires rare materials for the National Library and also overseas the map collections of the library. Makeswary has several years of experience in cataloguing, heritage collections management, reference and research, as well as in managing large-scale preservation projects.

REFERENCES

Bagrow, l. (1964). History of cartography. London: Watts. (Call no.: R 912.09 BAG)

Borschberg, P. (2010). The Singapore and Melaka Straits: Violence, security and diplomacy in the 17th century. Singapore: NUS Press. (Call no.: RSING 911.16472 BOR)

Burnet, I. (2011). Spice islands. Kenthurst, N.S.W.: Rosenberg Publishing. (Call no.: RSEA 380.141383 BUR)

Fell, R.T. (1991). Early maps of South-East Asia. Singapore: Oxford University Press. (Call no.: RSING 912.59 FEL)

National Library of Australia. (2013). Mapping our world: Terra Incognita to Australia. Canberra: National Library of Australia. (Call no.: R 912.94074 MAP)

Parry, D.E. (2005). The cartography of the east indian Islands = Insulae Indiae Orientalis. London: Country Editions. (Call no.: RSING q912.59 PAR)

Shirley, R.W. (1984). The mapping of the world: Early printed world maps, 1472–1700. London: Holland Press. (Not available in NLB holdings)

Speake, J. (Ed.). (2003). Literature of travel and exploration: An encyclopedia. New York: Fitzroy Dearborn. (Call no.: R q910.403 LIT)

Stefoff, R. (1995). The British Library companion to maps and mapmaking. London: British Library. (Call no.: R 912.03 STE)

Suarez, T. (1999). Early mapping of Southeast Asia. Hong Kong: Periplus Editions. (Call no.: RSING q912.59 SUA)

Tooley, R.V. (1979). Tooley’s dictionary of mapmakers. Hertfordshire: Map Collector Publications. (Not available in NLB holdings)

NOTES

-

Bagrow, l. (1964). History of cartography (p. 125). London: Watts. (Call no.: R 912.09 BAG) ↩

-

Shirley, R.W. (1984). The mapping of the world: Early printed world maps, 1472–1700 (pp. xxvii–xxviii). London: Holland Press. (Not available in NLB holdings) ↩

-

Stefoff, R. (1995). The British Library companion to maps and mapmaking (p. 115). London: British Library. (Call no.: R 912.03 STE) ↩

-

Shirley, 1984, pp. xxxviii–xxxix. ↩

-

Shirley, 1984, p. xxix. ↩

-

Suarez, T. (1999). Early mapping of Southeast Asia (p. 130). Hong Kong: Periplus Editions. (Call no.: RSING q912.59 SUA) ↩

-

Shirley, 1984, p. xxviii. ↩

-

National Library of Australia. (2013). Mapping our world: Terra Incognita to Australia (p. 90). Canberra: National Library of Australia. (Call no.: R 912.94074 MAP) ↩

-

Speake, J. (Ed.). (2003). Literature of travel and exploration: An encyclopedia (pp. 134–136). New York: Fitzroy Dearborn. (Call no.: R q910.403 LIT) ↩

-

Parry, D.E. (2005). The cartography of the east indian Islands = Insulae Indiae Orientalis (pp. 87–90). London: Country Editions. (Call no.: RSING q912.59 PAR); Speake, 2003, p. 135. ↩

-

Shirley, 1984, pp. 86–87. ↩

-

Fell, R.T. (1991). Early maps of South-East Asia (p. 28). Singapore: Oxford University Press. (Call no.: RSING 912.59 FEL) ↩

-

Burnet, I. (2011). Spice islands (p. 46). Kenthurst, N.S.W.: Rosenberg Publishing. (Call no.: RSEA 380.141383 BUR) ↩

-

Tooley, R.V. (1979). Tooley’s dictionary of mapmakers (p. 619). Hertfordshire: Map Collector Publications. (Not available in NLB holdings) ↩

-

Borschberg, P. (2010). The Singapore and Melaka Straits: Violence, security and diplomacy in the 17th century (p. 49). Singapore: NUS Press. (Call no.: RSING 911.16472 BOR) ↩

-

Tooley, 1979, p. 49. ↩

-

Tooley, 1979, p. 135. ↩