All Creatures Great and Small: Singapore's First Zoos

Few people are aware that the island’s first public zoo was set up in 1875. Lim Tin Seng traces the history of wildlife parks in Singapore.

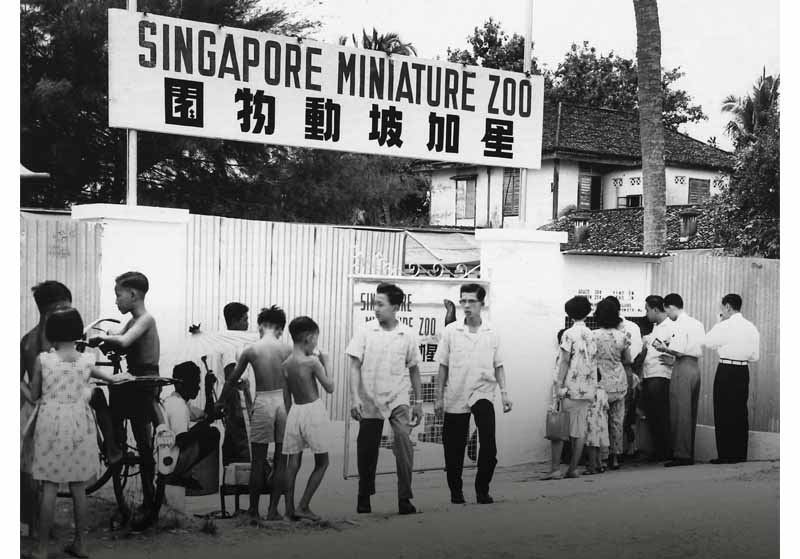

Entrance of the Singapore Miniature Zoo in Pasir Panjang that was started by Tong Seng Mun in 1957. Tong Seng Mun Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Entrance of the Singapore Miniature Zoo in Pasir Panjang that was started by Tong Seng Mun in 1957. Tong Seng Mun Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

The Singapore Zoo, located on a 26-hectare promontory in Upper Seletar Reservoir, is considered as one of the finest of its kind in the world. Home to over 2,800 animals from more than 300 species, the zoo has received a string of awards and accolades over the years. The zoo is part of a cluster of wildlife attractions in the vicinity, including the Night Safari and the River Safari, and serves as a centre for research in the areas of wildlife conservation, wildlife rescue and rehabilitation.1 The Singapore Zoo was set up in 1973, but unbeknownst to many, smaller animal enclosures have existed on the island since colonial times.

An Early Fascination for Wildlife

Zoology, a branch of natural history that studies all aspects of animals, was a subject that captivated the island’s colonial administrators, including its founder, Stamford Raffles. A keen natural historian, Raffles was deeply fascinated by the diversity of animals and plants of the East Indies. He regularly embarked on expeditions to explore the tropical flora and fauna of the region, and came across the Rafflesia, the giant parasitic flower named after him, and exotic wildlife such as the crab-eating macaque, moonrat, siamang, sun bear, white-crowned hornbill and barred eagle owl.2

Raffles maintained a menagerie when he was stationed in Penang, Malacca, Java and Sumatra. He kept a siamang, an elephant, two orangutans, a tiger and a sun bear. Many of the animals were given to him by Malay, Javanese and Sumatran rulers and, oddly, a few were tamed with a distinctly anthropomorphic slant.3 For instance, Raffles was said to have dressed his pair of orangutans in Malacca in human attire, and fed his sun bear Bencoolen champagne. The sun bear was raised together with his children in the same nursery and allowed to sit at his desk.4 Following his return to Singapore in October 1822, Raffles proposed in his Town Plan the creation of an animal enclosure with 200 spotted deer in a botanic garden – however this did not materialise.5

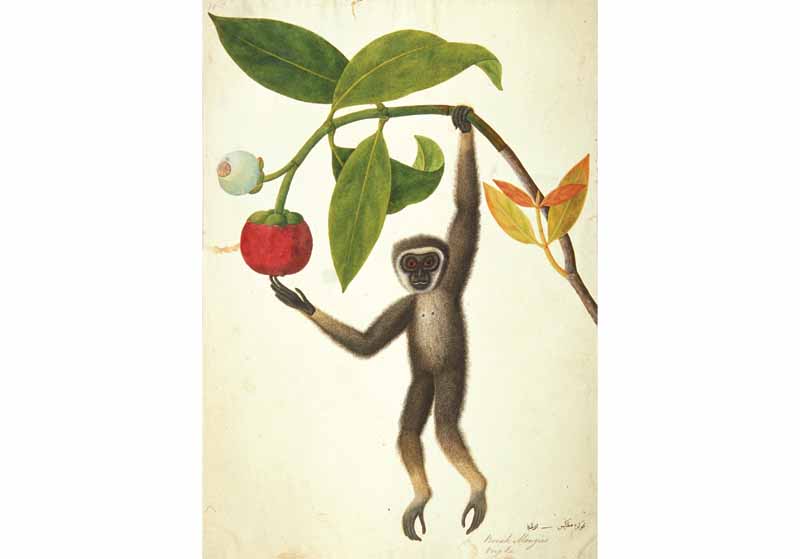

William Farquhar, the first resident of Singapore (1819–22), was also deeply interested in natural history and zoology. During his years as commandant and resident of Malacca between 1803 and 1818, Farquhar hired Chinese artists to document the flora, mammals, birds, reptiles, fish and insects of Malacca in close to 500 watercolour paintings. He also made a number of zoological discoveries in Malacca that included the Malayan tapir, binturong, banded linsang and bamboo rat. Farquhar similarly kept a menagerie at his residence that housed animals such as the leopard, wild cat, wild dog, porcupine, cassowary and binturong. He even owned a tiger, acquired when it was still a cub. Farquhar also reared many different types of birds as he was particularly interested in ornithology.6

Some prominent and well-off early settlers in Singapore, such as Chinese merchant Hoo Ah Kay, or Whampoa, were similarly interested in the wildlife of the region. In the 1850s, Whampoa established a private menagerie in the expansive gardens of his mansion along Serangoon Road.7 The menagerie was often cited by travellers as a must-see and comprised many rare birds and animals such as rhinoceroses, tapirs, giraffes and a bear.8 Whampoa had a pet orangutan that not only preferred cognac over water, but also possessed “manlike propensities” that could “win over some of his visitors to the Darwinian Theory”.9 Whampoa sent the remains of the orangutan to the Raffles Museum to be preserved after its death in 1878.10

The First Public Zoo

In 1867, Harry St George Ord, governor of the Straits Settlements (1867–73), suggested to the Agri-Horticultural Society that a zoological garden be established within the Botanic Gardens on Cluny Road for educational purposes.11 To encourage the effort, Ord offered the society two elephants, two tapirs, a leopard and a black panther in 1870, and a government grant to defray the cost of upkeeping them. The society declined Ord’s offer as it felt that it did not have the means to manage a zoo.12 In fact, the zoo that Ord envisioned did not materialise until after the society, overcome by debt, handed the gardens to the Gardens Committee appointed by the colonial government in January 1875. Henry James Murton, a botanist with Britain’s Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew, England, was hired as the superintendent of the Botanic Gardens. Murton immediately expanded the gardens and concurrently established the zoo.13

Murton hired William Krohn, a zoology expert, as the superintendent of the Zoological Garden.14 By 1877, the developed parts of the gardens were dotted with enclosures housing an impressive collection of about 150 animals. Many were gifts from administrators and dignitaries from Singapore and Malaya: the governor of the Straits Settlements, Andrew Clarke (1873–75), presented the zoo with a female two-horned rhinoceros, while the British resident of Perak, Ernest Birch, gave a sloth-bear, and the sultan of Terengganu gifted a tiger. The public also donated a pair of orangutans, a leopard, a number of deer and other small animals. The King of Siam gave the zoo a leopard and the Acclimatisation Society in Melbourne an emu, a great kangaroo, three bed kangaroos and a brush-tailed rock wallaby.15

This dark-handed gibbon hanging off a mangosteen tree is one of the paintings that William Farquhar commissioned Chinese artists to do between 1803 and 1818 when he was resident and commandant of Malacca. Courtesy of the National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board.

This dark-handed gibbon hanging off a mangosteen tree is one of the paintings that William Farquhar commissioned Chinese artists to do between 1803 and 1818 when he was resident and commandant of Malacca. Courtesy of the National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board.

However, the cost of upkeeping the animals soon exceeded the budget allocated to the zoo, and it faced problems in caring for the animals. By 1878, several enclosures had fallen into disrepair. Coupled with the loss of its only keeper, H. Capel, due to a dispute in pay, many of the bigger animals, including the rhinoceros, leopard and two kangaroos died due to poor living conditions. In a bid to stem further losses and reduce its overheads, Murton, Krohn and the Gardens Committee decided to limit the collection to only birds and small animals in 1878. The larger animals were sent to the Calcutta Zoological Gardens in exchange for several Indian bird species.16

The scaled-down Botanic Gardens zoo was now able to operate within budget. In fact, by 1880 many of the enclosures had been repaired,17 and new aviaries and enclosures were built to house its growing bird and small animal collection. Residents once again donated animals to the zoo. Some of the animals it received during this period include the Asian golden cat from Pahang (1893), the Indian jackal (1895) and the dingo from Australia (1893). At the turn of the century, the zoo collection, as Henry Nicholas Ridley, director of the Botanic Gardens, wrote, “had become the very representative of the fauna of the Malay Peninsula and islands”.18

Ridley held high regard for the Botanic Gardens zoo, describing it as an attraction that “was known all over the world, and the first thing asked for by visitors”. He saw the zoo as a means for researchers and the public to learn about animal behaviour objectively. He wrote, “The only way of knowing what an animal thinks is to keep it comfortable and snug and observe its ways. It will soon let you know what it likes, which probably does not at all fall in with your ideas of what it ought to like”.19 The public began urging the government to allocate more funds for the zoo to improve its infrastructure but as the cost of its upkeep was too high, the government decided in 1903 to sell all the animals and birds and shut down the zoo.

Basapa’s Private Zoo

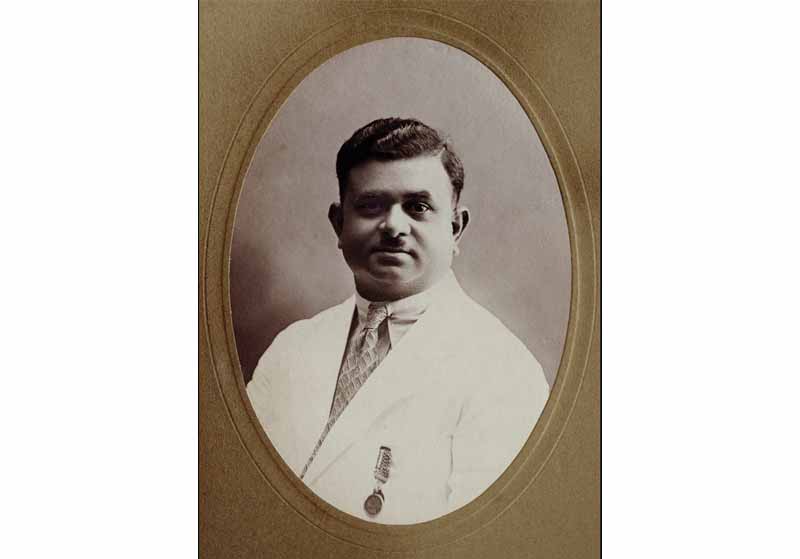

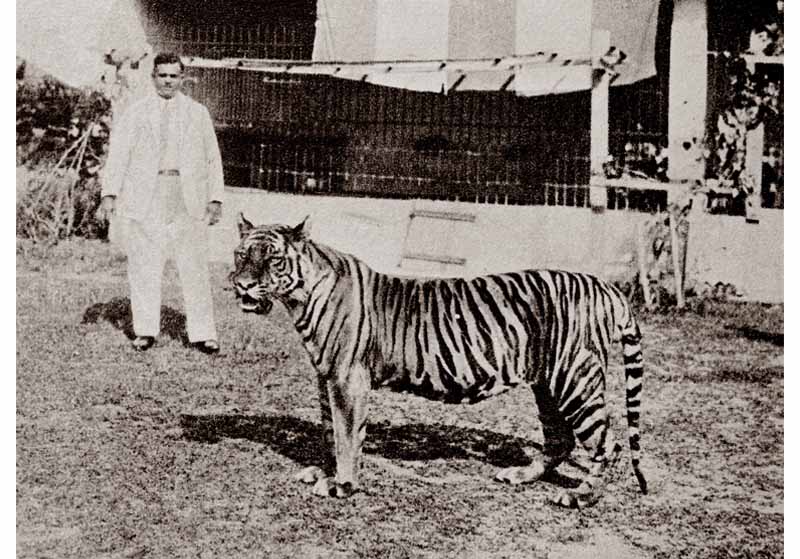

The next zoo was a private venture by William Lawrence Soma Basapa in 1928.20 Basapa was an Anglican Indian landowner who had an unequivocal passion for animals. In fact, he was an animal trader by profession, and had a pet Bengal tiger named Apay, which he led around with a chain since it was four years old. In the early 1920s, Basapa converted part of his estate at 317 Serangoon Road into a space for his collection of animals and birds.21 Among the first who visited Basapa’s private menagerie was Albert Einstein, the father of modern physics, who described it as a “wonderful zoological garden” when he visited Singapore in 1922.22 Unfortunately, Basapa had to relocate his animals in 1928 when his neighbours, the Rural Board and even his wife complained about the noise and the stench of his zoo.23

William Lawrence Soma Basapa. Courtesy of the Basapa Family.

William Lawrence Soma Basapa. Courtesy of the Basapa Family.

William Lawrence Soma Basapa with his favourite pet Bengal tiger Apay. Courtesy of the Basapa Family.

William Lawrence Soma Basapa with his favourite pet Bengal tiger Apay. Courtesy of the Basapa Family.

The new 11-hectare site for his animals was situated on Punggol Road. Although it was a deserted mangrove swamp overgrown with weeds, bushes and coconut palms, Basapa was able to transform it into a working zoological garden. By 1930, the zoo, which was called the Singapore Zoo, had become quite respectable, attracting large numbers of visitors, particularly during weekends.24 Other than showcasing animals native to the Malay Peninsula and Borneo such as the Malayan tiger, Malayan tapir, spotted leopard and orangutan, Basapa also imported animals that were entirely new to Singapore in order to make the collection interesting for visitors.25

The first animals that arrived from overseas in 1930 included three seals from the US, a pair of lions from Africa and some rare birds from South America.26 In 1935, the zoo witnessed one of the biggest shipments of animals when the Norddeutscher Lloyd cargo steamer Neckar arrived from Germany with “her top and main decks crammed with boxes and crates containing a remarkably varied collection of animals and birds”. Described as a veritable “Noah’s Ark” by the press, some of the wildlife the steamer was carrying included two African lions, 15 African grey parrots, four Brazilian blue-necked turakos, two pairs of white swans, two Angola cats, a pair of Brazilian trumpet birds and a pair of silver marmozets.27 The zoo had previously received a chimpanzee from France, a pair of polar bears from Germany and the monkey-eating eagle from the Philippines.28 Through regular animal exchanges with Sydney’s Taronga Zoo, Basapa was able to introduce Australian wildlife such as the Wagga Wagga pigeon, golden shoulder parakeet, Tasmanian devil and kangaroo.29

By 1936, Basapa had amassed a collection of about 200 animals and some 2,000 birds, turning his zoo into a major attraction in pre-war Singapore. In the 1936 edition of the Willis’ Singapore Guide, the definitive travel guide of the time, the zoo was described as a place where visitors could indulge in a unique experience viewing animals in their primitive state, enjoying refreshment at an affordable price, and mingling with two friendly free-roaming chimpanzees that were most willing to pose for photographs.30 As the zoo cost about $35 daily to maintain, Basapa charged an admission fee of 40 cents for adults and 20 cents for children, which was considered pricey back then.31 Nonetheless, many locals visited the zoo as it was a novelty. Local resident Mohinder Singh said, “People used to visit it because they couldn’t see any other. There was no other. Even Johore Zoo which Tengku started was also very small, [and] was started later”.32 The zoo was also commended by prominent individuals, including Roland Braddell, barrister and joint editor of One Hundred Years of Singapore. He wrote in The Lights of Singapore. 33

The Singapore Zoo at Ponggol [is] a truly delightful place that has the full approval of the local authorities. Here you will see a magnificent collection of birds, amongst which the crown pigeons are said to be the best in the world. The orangutans are really happy here and in a climate natural to them…As it is, I think the town owes much to Mr Basapa’s very courageous lone effort in providing with us what is a very great attraction… A trip to the zoo is one of the things that no visitor should omit, it has a personality entirely its own, and is pitched in beautiful surroundings on the Straits of Johore.

Unfortunately, Basapa’s zoo suffered during the Japanese invasion of Singapore in January 1942. In preparation for the assault of the Japanese from Johor, the British deployed troops to defend the northern coastline of Singapore, including Punggol coast. The zoo was ordered to close and Basapa was given only 24 hours to move his birds and animals elsewhere. Unable to find another location at such short notice, many of Basapa’s animals were either killed or released into the wild.34 The Japanese subsequently took over the zoo compound to store their supplies. Heartbroken, Basapa passed away shortly after, in 1943.35

Asia’s Best Zoo

Shortly after gaining Independence in 1965, discussion for a public zoo surfaced when then chairman of the Public Utilities Board (PUB) Ong Swee Law proposed in January 1968 to set one up in the Upper Seletar Reservoir Catchment forest. The aim was to utilise the land around the reservoir for recreational purposes and create a space for family outings.36 Ong set up a committee in April 1968 comprising PUB officials to study the feasibility of a new Singapore zoo.37 During the course of the study, the committee consulted with many zoological experts from zoos and zoological societies around the world to make up for their lack of knowledge on the subject.

When the committee’s report was submitted to the government in September 1969, senior officials and cabinet members, including then Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew, were startled by the proposal. Lee, in particular, was concerned about two things: First, situating a zoo in the middle of a reservoir could pollute the nation’s precious water supply, and second, the zoo might become a dirty and smelly place.

To allay these fears, the committee emphasised that the zoo would adhere to a high standard of cleanliness and hygiene. It also proposed having a storm drain around the perimeter of the zoo’s compound to separate it from the reservoir, and its own sewage treatment plant to process human and animal waste. The processed waste would be pumped away from the water catchment area via a 4.5-km-long pipeline into the Mandai River. The committee had also given considerable thought to how the zoo would sustain itself, promising to avoid the financial pitfalls of other zoos by having affordable admission charges, running restaurants and shops, and seeking grants and donations.38 All this might seem par for the course today, but one has to remember this was 1969 and Singapore’s leaders were more concerned with creating jobs and addressing public housing woes rather than building recreational facilities for its people.

However, right from the start the planners had a good idea of how they would manage the zoo – from the animal species to exhibit to the number of staff to hire – and they persevered. As a result, the zoo proposal gained the support of Finance Minister Goh Keng Swee and Law Minister E. W. Baker who in turn convinced the other ministers, including Lee, to support the idea.39 In September 1969, the government gave its approval and a public limited company, Singapore Zoological Gardens, was set up to oversee the construction and management of the zoo. The government also allocated S$9 million for its construction, and two experts – Lyn de Alwis of Sri Lanka’s Dehiwala Zoo and A.G. Alphonso, director of the Singapore Botanic Gardens – were appointed as consultants.40

De Alwis was instrumental in conceptualising the zoo’s design. The “open concept” design framework that de Alwis employed at the Dehiwala Zoo dispensed with cages, even for the big cats. Instead, the animals were to be kept in open enclosures that resembled their natural habitats.41 Alphonso made a concerted effort to landscape the zoo such that it blended into the surrounding rainforest. During the construction phase from 1971 to 1973, some 2,000 new trees and plants were added to give the zoo a lush and tropical appearance.42 As the zoo neared completion, it started receiving pets and animal captures from the public. Surprisingly, these included gibbons, macaques, mousedeer and an orangutan named Zabu.43 A staff of some 130 personnel – including the first batch of keepers Png Bee Chye, Subash Chandran, B. Dhanapala and Sim Siang Huat – were hired to care for the animals.44 When it officially opened on 27 June 1973 as the Singapore Zoological Gardens, it had a modest collection of 272 animals from 72 species held in about 50 enclosures.45

Despite charging an entrance fee of S$2 for adults and S$1 for children, considered high at the time, the zoo was able to welcome its one-millionth visitor on 30 November 1974, less than two years after it opened.46 Throughout the 1970s, the zoo would register over 500,000 visitors annually, and by the time it received its 10-millionth visitor in August 1987, it was attracting nearly a million visitors a year.47 The popularity of the Singapore Zoological Gardens (which was renamed Singapore Zoo in 2005) was largely due to its canny ability to introduce new and innovative attractions and programmes. Between the 1980s and the turn of the millennium, the zoo rolled out one attraction after another in quick succession – from Breakfast with Ah Meng, the zoo’s star orangutan, to choreographed animal shows that were meant to educate visitors. It also added many endangered animals to its collection through loans, gifts or acquisitions, including the Siberian tiger, golden lion tamarind, Komodo dragon, golden monkey, Russian brown bear, red panda lemur, polar bear, koala, snow leopard and gorilla.48

All this while, the zoo held steadfast to its open concept and exhibited the animals thematically. One of the first of such enclosures was the Fragile Forest in November 1988, which recreated a rainforest habitat with species such as lemurs, sloths, flying foxes and butterflies.49 Other major thematic enclosures followed: Wild Africa (1991), Primate Kingdom (1991) and Great Rift Valley of Ethiopia (2001).50 On 3 May 1994, the zoo took these thematic enclosures to a new level by unveiling the world’s first Night Safari. The 35-hectare park allows visitors to observe nocturnal animals in settings that imitate natural habitats such as the Himalayan Foothills and Equatorial Africa.

Many of these attractions were conceived during Bernard Harrison’s term as executive director from 1981 to 2002. After graduating from the University of Manchester with double honours in zoology and psychology, Harrison joined the zoo as an assistant administrative officer in 1973 and rose through the ranks. With his shaggy hair and preference for T-shirts and cargo shorts over designer suits, Harrison was affectionately regarded by employees as a bohemian Tarzan of sorts. However, beneath his laid-back appearance was a deep and abiding interest in animals. With his creativity and willingness to think big and take risks in executing bold ideas, Harrison was able to transform the Singapore Zoo into what it is today.51

A couple riding an elephant at the Singapore Zoological Gardens in the mid-1980s. Singapore Tourist Promotion Board Collection. Courtesy of Singapore Tourist Promotion Board (STPB) Collection, National Archives of Singapore.

A couple riding an elephant at the Singapore Zoological Gardens in the mid-1980s. Singapore Tourist Promotion Board Collection. Courtesy of Singapore Tourist Promotion Board (STPB) Collection, National Archives of Singapore.

Deers inside a fenced enclosure at the Singapore Zoological Gardens in 1973. Courtesy of Ho Seng Huat.

Deers inside a fenced enclosure at the Singapore Zoological Gardens in 1973. Courtesy of Ho Seng Huat.

What’s Next?

The most recent jewel in the wildlife crown is the 12-hectare River Safari, Asia’s first river-themed wildlife park that opened in February 2014. Just months later, in September, Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong announced that the zoo precinct in Mandai, encompassing the Singapore Zoo, Night Safari and River Safari, would be revamped and developed into a world-class nature themed attraction. The development would be led by the Singapore Tourism Board and Temasek Holdings, the majority shareholder of Wildlife Reserves Singapore (WRS), which runs the three zoos as well as Jurong Bird Park. Although developers have yet to announce concrete plans, bold moves such as having a fourth zoo, moving Jurong Bird Park to Mandai, as well as the construction of new public spaces, waterfront trails and green spaces for visitors to view wildlife in their natural habitats are said to be in the works.52

A COTERIE OF PRIVATE ZOOS

The Singapore Zoo at Punggol was not the only private zoo in Singapore during the colonial period. As wildlife trade was unregulated at the time, Singapore became a wildlife trading hub, leading to the establishment of a number of private zoos.53 Among them was Tong Seng Mun’s Singapore Miniature Zoo at Pasir Panjang. Opened in 1957, it was home to many bird and animal species such as lions, bears, a camel and a rhinoceros. There was also a zoo off Tampines road, which was started in 1954 by L.F. de Jong. It reportedly housed cassowaries, tapirs, leopards, gibbons, crocodiles and snakes. Another zoo, called Mayfield Kennels and Zoo and owned by Herbert de Souza, was located on East Coast Road in the early 1950s. Here, visitors could purchase animals ranging from white mice to giant pythons and even elephants.54 Besides Basapa’s zoo in Punggol, there was another opened by the Chan brothers in the same area in 1963. The zoo, however, went bankrupt in the early 1970s and its animals and birds were auctioned off.55

Lim Tin Seng is a Librarian with the National Library of Singapore. He is the co-editor of Roots: Tracing Family Histories – A Resource Guide (2013); Harmony and Development: ASEAN-China Relations (2009) and China’s New Social Policy: Initiatives for a Harmonious Society (2010).

REFERENCES

Abdullah bin Abdul Kadir. (2009). The Hikayat Abdullah. Kuala Lumpur: The Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society. (Call no.: RSEA 959.9 ABD)

Bastin, J. (1981). The letters of Sir Stamford Raffles to Nathaniel Wallich, 1819–1824. Journal of the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, 54 (2) (240), 1–73. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website.

Bastin J. (1990). Sir Stamford Raffles and the study of natural history in Penang, Singapore and Indonesia. Journal of the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, 63 (2) (259), 1–25. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website.

Bastin, J., et. al. (2010). Natural history drawings: The complete William Farquhar collection, Malay Peninsula, 1803–1818. Singapore: Editions Didier Millet. (Call no.: RSING 759.959 NAT)

Burkill, I.H. (1918, August 12). The establishment of the Botanic Gardens, Singapore. Gardens’ bulletin, Straits Settlements, 2 (2), 55–72.

Burkill, I.H. (1918, November 11). The second phase in the history of the Botanic Gardens, Singapore. Gardens’ bulletin, Straits Settlements, 2 (3), 93–108.

Raffles, S. (1991). Memoir of the life and public services of Sir Thomas Stamford Raffles. Singapore: Oxford University Press. (Call no.: RSING 959.57021092 RAF)

Ridley, H.N. (1906, December). The menagerie of the Botanic Gardens. Journal of the Straits Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, 46, 133–194. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website.

Sharp, I. (1994). The first 21 years: The Singapore Zoological Gardens story. Singapore: Singapore Zoological Gardens. (Call no.: RSING q590.7445957 SHA)

Singapore Zoological Gardens. (1973). Official opening by Dr. Goh Keng Swee, Deputy Prime Minister and Minister of Defence Wednesday 27th June 1973: Souvenir programme. Singapore: Singapore Zoological Gardens. (Call no.: RSING 590.7445957 SIN)

Singapore Zoological Gardens. (1973). Official guidebook. Singapore: Singapore Zoological Gardens. (Call no.: RSING 590.7445957 SIN)

Singapore Zoological Gardens. (1986). The Singapore Zoological Gardens: A tropical garden for animals. Singapore: Singapore Zoological Gardens. (Call no.: RSING 590.7445957 SIN)

Singh, K. (2014). Naked ape, naked boss: Bernard Harrison: The man behind the Singapore Zoo & the world’s first Night Safari. Singapore: Marshall Cavendish. (Call no.: RSING 590.735957092 SIN)

Song, O.S. (1984). One hundred years’ history of the Chinese in Singapore. Singapore: Oxford University Press. (Call no.: RSING 959.57 SON)

Willis, A.C. (1936). Willis’ Singapore guide. Singapore: Alfred Charles Willis. Retrieved from BookSG. (Call no.: RRARE 959.57 WIL; Microfilm no.: NL9039)

NOTES

-

Singapore Zoo. (2014). Park experience. Retrieved from Singapore Zoo website; Wildlife Reserves Singapore Group. (2014). Fast facts: Singapore Zoo. Retrieved from Wildlife Reserves Singapore website. ↩

-

Bastin J. (1990). Sir Stamford Raffles and the study of natural history in Penang, Singapore and Indonesia. Journal of the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, 63 (2) (259), 1–25, pp. 1–2. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website; Raffles, S. (1991). Memoir of the life and public services of Sir Thomas Stamford Raffles (pp. 633–697). Singapore: Oxford University Press. (Call no.: RSING 959.57021092 RAF) ↩

-

Bastin, 1990, pp. 3–4. ↩

-

Bastin, 1990, p. 3; Abdullah bin Abdul Kadir. (2009). The hikayat Abdullah (p. 77). Kuala Lumpur: The Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society. (Call no.: RSEA 959.9 ABD) ↩

-

Bastin, J. (1981). The letters of Sir Stamford Raffles to Nathaniel Wallich, 1819–1824. Journal of the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, 54 (2) (240), 1–73, pp. 16–17. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website. ↩

-

Bastin, J., et. al. (2010). Natural history drawings: The complete William Farquhar collection, Malay Peninsula, 1803–1818 (pp. 7, 9–10, 26, 29). Singapore: Editions Didier Millet. (Call no.: RSING 759.959 NAT) ↩

-

Song, O.S. (1984). One hundred years’ history of the Chinese in Singapore (p. 53). Singapore: Oxford University Press. (Call no.: RSING 959.57 SON) ↩

-

Chinese enterprise in Singapore: Unicorn’s horns. (1935, October 8). The Singapore Free Press, p. 4. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

‘Whampoa’ was the first of Singapore’s towkays. (1954, March 13). The Straits Times, p. 9. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

News of the Week. (1878, July 6). Straits Times Overland Journal, p. 6. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Burkill, I.H. (1918, August 12). The establishment of the Botanic Gardens, Singapore. Gardens’ bulletin, Straits Settlements, 2 (2), 55–72, p. 61. ↩

-

The Botanical Garden. (1870, March 1). Straits Times Overland Journal, p. 3. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Burkill, I.H. (1918, November 11). The second phase in the history of the Botanic Gardens, Singapore. Gardens’ bulletin, Straits Settlements, 2 (3), 93–108, pp. 93–94. ↩

-

Legislative Council: Supply Bill 1875. (1874, December 28). Straits Observer (Singapore), p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Ridley, H.N. (1906, December). The menagerie of the Botanic Gardens. Journal of the Straits Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, 46, 133–194. p. 133. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website. ↩

-

Ridley, Dec 1906, pp. 134–136. ↩

-

Yuen, S. (2012, July 15). Our forgotten zoo. The New Paper, pp. 18–19. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Wong, L.Q. (2013, October 29). Singapore’s first zoo. Mnemozine, 5, 33. Retrieved from National University of Singapore, Department of History website. ↩

-

Zaccheus, M. (2013, April 6). First zoo in Singapore rated ‘wonderful’ by Einstein. The Straits Times, p. 18. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Wong, 29 Oct 2013, p. 33. ↩

-

Ponggol Zoo. (1930, March 17). The Straits Times, p. 12. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Animals arriving few by few. (1936, November 9). The Straits Times, p. 12; These “Moos” make zoo news. (1937, July 4). The Straits Times, p. 3. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The Straits Times, 17 March 1930, p. 12. ↩

-

“Noah’s Ark” arrives in Singapore. (1935, August 5). The Singapore Free Press, p. 9. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Chimp for Ponggol Zoo. (1937, May 24). The Straits Times, p. 13; Polar bears in Singapore. (1937, March 13). The Singapore Free Press, p. 3; Monkey-eating eagle. (1937, December 9). The Straits Times, p. 13. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

More animals for Ponggol Zoo. (1937, February 26). The Straits Times, p. 16. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Willis, A.C. (1936). Willis’ Singapore guide (pp. 118–119). Singapore: Alfred Charles Willis. Retrieved from BookSG. (Call no.: RRARE 959.57 WIL; Microfilm no.: NL9039) ↩

-

Scenes at Singapore’s Zoo. (1938, September 25). The Straits Times, p. 32. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Pitt, K.W. (1985, September 16). Oral history interview with Mohinder Singh [Transcript of MP3 recording no. 000546/65/58, p. 583]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

Braddell, R. (1934). The lights of Singapore (pp. 124–125). London: Methuen & Co. (Call no.: RRARE 959.57 BRA; Microfilm: NL25437; Accession no.: B29033830F) ↩

-

S’pore zoo starts from scratch. (1946, October 20). The Straits Times, p. 5. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Wong, 29 Oct 2013, p. 33. ↩

-

The men behind the project. (1973, January 29). The Straits Times, p. 14. Retrieved from NewspaperSG; Singapore Zoological Gardens. (1973). Official opening by Dr. Goh Keng Swee, Deputy Prime Minister and Minister of Defence Wednesday 27th June 1973: Souvenir programme (pp. 6, 8). Singapore: Singapore Zoological Gardens. (Call no.: RSING 590.7445957 SIN) ↩

-

Singapore Zoological Gardens, 1973, p. 8. ↩

-

Singapore Zoological Gardens, 1973, pp. 4–5, 11–12. ↩

-

Singapore Zoological Gardens, 1973, pp. 11–12. ↩

-

Singapore Zoological Gardens,1973, pp. 7–8; The Straits Times, 29 Jan 1973, p. 14; Govt’s $5 mil firm to set up a zoo. (1971, April 24). The Straits Times, p. 11. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

De Alwis – man who planned the Mandai zoo. (1973, July 8). The Straits Times, p. 4; Fong, L. (1971, April 28). Animals at zoological gardens will not be caged. The Straits Times, p. 17. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Sharp, I. (1994). The first 21 years: The Singapore Zoological Gardens story (pp. 12, 20–21). Singapore: Singapore Zoological Gardens. (Call no.: RSING q590.7445957 SHA); Campbell, W. (1973, January 29). Singapore Zoological Gardens take shape. The Straits Times, p. 14. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Meet the keepers. (1973, February 1). The Straits Times, p. 14. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Sharp, 1994, p. 29; Singapore Zoological Gardens. (1975). “Mr. Million’s lucky day”. Zoo-m, 3, 3. ↩

-

Zoo’s millionth visitor walks in to a jumbo surprise. (1987, December 7). The Straits Times, p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Lee, J. (1998, November 8). Zoo unveils the Fragile Forest. The Straits Times, p. 32. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Wild Africa opens at Singapore Zoo. (1991, April 30). The Straits Times, p. 24; Zoo’s Primate Kingdom features eight new species of monkeys and lemurs. (1991, June 23). The Straits Times, p. 16; Chia, E. (2001, December 1). Ethiopia in the zoo. Today, p. 27. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Mok, F.F. (2015, January 15). STB, Temasek to lead Mandai zoo revamp. My Paper. Retrieved from AsiaOne website. ↩

-

Zaccheus, M. (2014, June 3). We brought a zoo: Singapore’s small havens for wild animals. The Straits Times. Retrieved from Factiva via NLB’s eResources website. ↩

-

Lee, T.S. (1953, April 27). You can buy or a mongo a mouse— se FROM MR. de SOUZA. The Singapore Free Press, p. 8. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The Straits Times, 3 Jun 2014. ↩