Through the Eye Glass

Title: Cermin Mata Bagi Segala Orang Yang

Menuntut Pengetahuan (An Eye Glass for All Who Seek Knowledge)

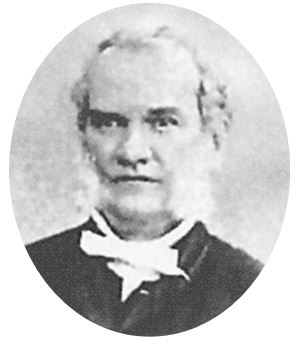

Authors: Possibly a collaboration between Reverend Benjamin Keasberry (1811–75) and Abdullah bin Abdul Kadir (1797–1854)

Year published: 1859

Publisher: Mission Press (Singapore)

Language: Malay

Type: Serial; 7 issues (only issues 4, 5, 6 and 7 are available in the National Library as a single bound copy)

Call no.: RRARE 059.9923 CER

Accession no.: B03057034K

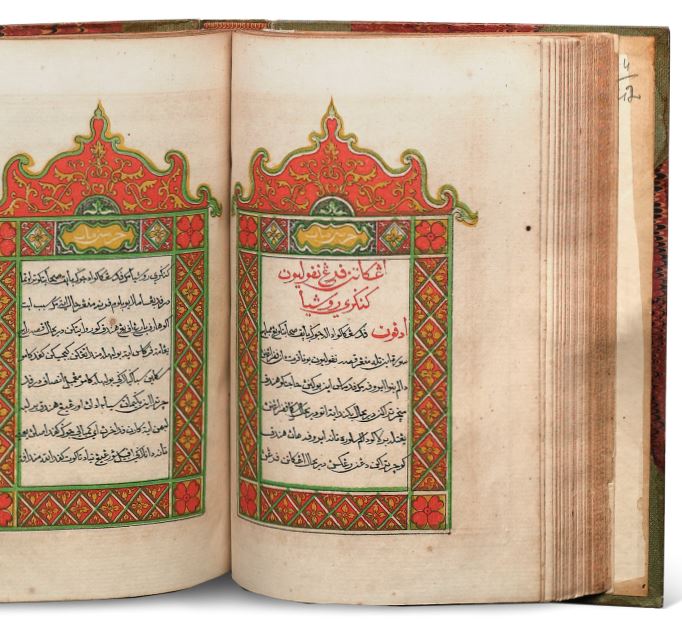

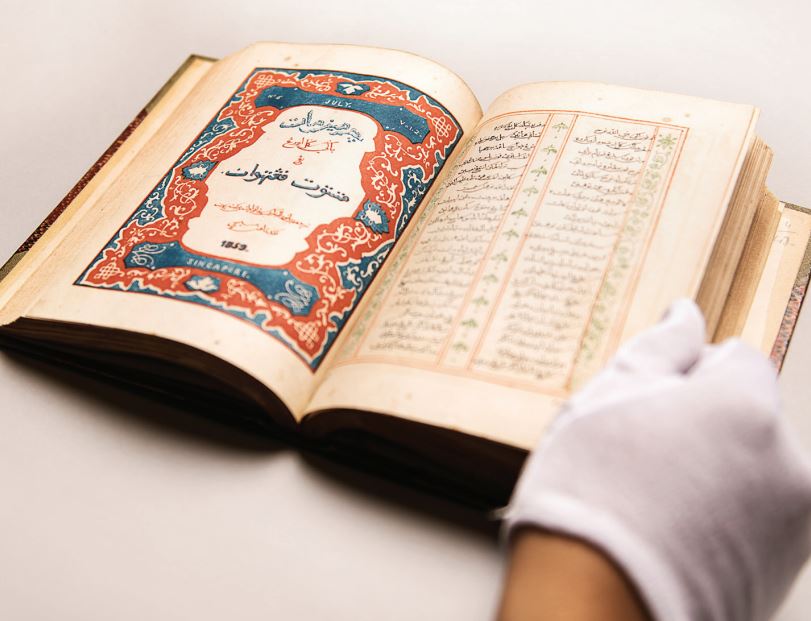

The journal Cermin Mata Bagi Segala Orang Yang Menuntut Pengetahuan is among the earliest Malay serial publications existing today. Translated literally as An “Eye Glass for All Who Seek Knowledge”, it was one of the most ambitious and voluminous of all 19th-century missionary journals printed in Malaya.1 Seven issues of Cermin Mata in Jawi – the modified Arab script used to write the Malay language – were produced as quarterly publications beginning from April 1858. Each issue contains 100 pages and comes with elaborate, coloured frontispieces and chapter headings.

The man behind Cermin Mata was Reverend Benjamin Keasberry, a Protestant missionary who moved to Singapore in 1839 when he saw the potential for doing missionary work among the Malays while assisting at the Mission Press.

Established by Christian missionaries in 1823, Mission Press is the first printing press established in Singapore. The press was specifically set up to print Christian literature that had been translated into various languages for distribution throughout the region. When the London Missionary Society ceased operations in Singapore in 1846, Keasberry decided to remain behind. Having learnt the art of printing in Batavia (present-day Jakarta), he took over the operations of the press and ran it as a commercial enterprise to support his family while running a school for Malay boys.2

Keasberry translated numerous English works into Malay, many of which supported the proselytising works of Christian missionaries. These ranged from books of the Bible such as Genesis and Psalms to literature on Jesus and other biblical characters. He was also known as a printer and publisher of textbooks for use in mission schools. Some of these textbooks were translated into Malay by Abdullah bin Abdul Kadir (also known as Munsyi Abdullah).3 Abdullah, a devout Muslim of Arab-Indian heritage, collaborated with Keasberry on various publications as copyist, writer, language editor, translator and printer.4

Keasberry met Abdullah in the late 1830s, when the latter was engaged to help him refine his Malay-language skills. The collaboration between Abdullah and Keasberry produced several beautifully decorated multi-coloured lithographs of fine manuscripts.

Keasberry’s boarding school for boys was set on a hill he had acquired in 1848 at River Valley Road, which he renamed Mount Zion. His students were taught English and Malay as well as skills such as printing, lithography, bookbinding and compositors’ work in both English and Malay type.5 Mount Zion (or Bukit Zion) was also the location of the press.

Keasberry compiled two periodicals before he published Cermin Mata: namely Taman Pengetahuan (1848–52) and Pŭngutib Sagala Remah Pengetahuan (1852–54). Similar in content to Cermin Mata, these works consisted of a mix of Christian biblical and other moral stories as well as practical knowledge and science.6 However of the three periodicals, the finest was Cermin Mata – which has been called “a most spectacular imprint”.7

Cermin Mata was used as an educational magazine and a means of proselytising in missionary schools. It was also used as reading material in the Dutch education system in Indonesia (after Dutch official Palmer van den Broek compiled parts of it as an anthology).8 This version in romanised text, or Rumi, was printed in 1866 in Batavia, followed by a Javanese version that was printed in 1877 in Semarang.9 A literal translation of the chapter titles from issues 5 and 6 shows interesting and varied content, with chapters such as “Tears of a Friend”, “Travels in Africa”, “About Sheep”, “Economics”, “Napoleon’s Army in Russia”, “Sailing Around the World” and “Robinson Crusoe”.10

Keasberry’s body of work was an important development for the Malay printing industry. He used the lithography technique to print Jawi text that resembled the natural flow of the handwritten script. Cermin Mata best demonstrates the advantages of this technique with its beautifully illustrated frontispiece. For the Malay world, this technique provided a cheap way of reproducing Jawi writing. It was enthusiastically embraced by local printers and publishers, paving the way for Singapore to become an important publishing centre in the Malay world.

– Written by Mazelan Anuar

NOTES

-

Warnk, H. (2010). The collection of 19th century printed Malay books of Emil Luring. International Journal of the Malay World and Civilisation, 28 (1), 124. Retrieved from UKM website. ↩

-

National Library Board. (2008). Mission Press written by Lim, Irene. Retrieved from Singapore Infopedia. ↩

-

National Library Board, 2008. ↩

-

Putten, J. V. D. (2006). Abdullah Munsyi and the missionaries. Bijdragen tot de Taal -, Land-en Volkenkunde (BKI), 162 (4), 411. Retrieved from Brill Online Books and Journals website. ↩

-

National Library Board. (1998). Benjamin Keasberry written by Cornelius-Takahama, Vernon. Retrieved from Singapore Infopedia. ↩

-

Putten, 2006, p. 411. ↩

-

Gallop, A. T. (1990). Early Malay printing: An introduction to the British Library collections. Journal of the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, 63 (1) (258), 98. Retreived from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website. ↩

-

Putten, 2006, p. 418. ↩

-

Proudfoot, I. (1993). Early Malay printed books: A provisional account of materials published in the Singapore-Malaysia area up to 1920, noting holdings in major public collections (p. 201). Kuala Lumpur: Academy of Malay Studies and the Library, University of Malaya. Call no.: RSING 015.5957 PRO-[LIB] ↩