About Law and Order

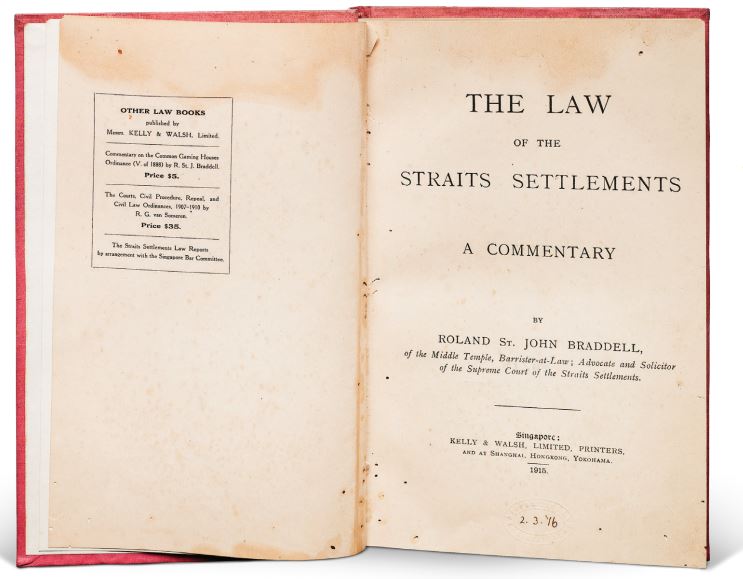

Title: The Law of the Straits Settlements: A Commentary

Author: Roland St. John Braddell (1880–

1966)

Year published: 1915

Publisher: Kelly & Walsh (Singapore)

Language: English

Type: Book; 278 pages

Call no.: RRARE 348.5957026 BRA

Accession nos.: B03003248I; B03003252D

The implementation of English law in Singapore, along with Penang and Melaka, is detailed in Roland St. John Braddell’s landmark The Law of the Straits Settlements: A Commentary. Although this book is not the first attempt at documenting the legal history of Singapore, it has, nonetheless, contributed significantly to its study, and is regarded as a classic by scholars even today.1

Singapore’s legal system can trace its origins to the British colonial era when it first adopted the English legal system. The First Charter of Justice Singapore was established on 6 February 1819, when Stamford Raffles signed a treaty with Sultan Husain Shah of Johor and Temenggung Abdul Rahman to establish a trading post in Singapore. Earlier in 1807, the British Crown had granted the British East India Company the First Charter of Justice to establish a Court of Judicature in Penang.2

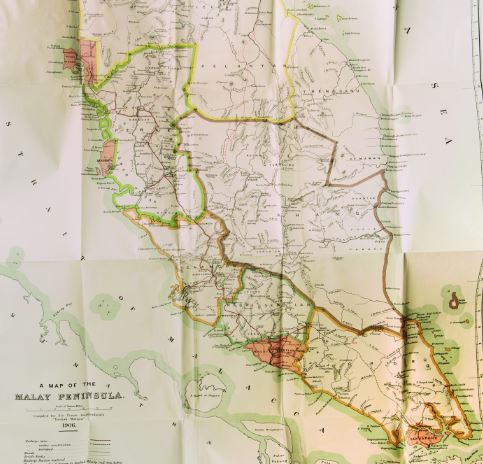

As Singapore’s population increased and commercial activity grew, it became clear that the administration of law on the island was inadequate to prevent and control crime. The promulgation of the Second Charter of Justice on 27 November 1826 – the year Singapore became part of the Straits Settlements together with Melaka and Penang – marked a watershed in Singapore’s legal history. The charter created the Court of Judicature of Singapore, Prince of Wales Island (Penang) and Melaka. It also introduced a single system of law and order for all inhabitants of Singapore and established a proper legal system based on English common law.3

However, not all English laws were suited for the Straits Settlements, and the colonial judges had to adapt the laws to suit the local context, especially in matters relating to religion, local manners and customs.4 Modifications were made mainly to several aspects of family law, such as those concerning marriage, divorce, adoption and succession. For example, Chinese polygamous marriages were recognised so that secondary wives and their children would be provided for.

In areas of law that affected British commercial interests, such as contract, commercial law, procedure and evidence, English law was adopted, completely replacing indigenous laws. This was to ensure uniformity of law throughout the British Empire and to protect the commercial interests of the East India Company.5

The Law of the Straits Settlements was first published in 1915, followed by a second edition in 1931. It was reprinted with an introduction by M. B. Hooker in 1982. The book comprises four chapters – Legal History; Modifications of English Law; Institutions of Government; and The Judiciary and the Bar – and five appendices on treaties; parliamentary acts; letters patent, instructions and standing orders; case references and the related ordinances; and decisions on the applicability of the English statutes.6

In his preface, Braddell acknowledged that the book was modelled after Walter J. Napier’s An Introduction to the Study of the Law Administered in the Colony of the Straits Settlements (1898), and was meant to be an update and expansion of Napier’s work. Although Napier’s publication is a small 52-page booklet comprising just three chapters, it was considered important for its discussion on the application of English law in the former British colonies.

By the 1850s, however, there was much dissatisfaction with the quality of justice administered in Singapore. In 1853–54, Chinese immigration levels reached a new peak when men involved in the civil war in southern China began pouring into Singapore in large numbers. This resulted in much unrest and bloodshed, necessitating stricter legislation and law enforcement and the administration of justice.

In particular, there was a need to reorganise the structure of the court in order to provide for a separate division with its own Recorder serving just Singapore and Melaka. This was made possible by the Third Charter of Justice of 12 August 1855.7 Under the charter, the Court of Judicature was reorganised into two divisions: the first division had jurisdiction over Singapore and Melaka, while the second division had jurisdiction over the Prince of Wales Island and Province Wellesley.8

The next milestone in Singapore legal history – which marked the coming of age of Singapore’s legal system – was the enactment of the Application of the English Law Act in November 1993. The act clarified the extent to which English law is applicable in Singapore, and removed much of the uncertainty about how it applied in the past. It also reduced reliance on English law and made Singapore’s commercial law independent of legislative changes in the United Kingdom, in line with Singapore’s status as a sovereign and independent nation.9

– Written by Irene Lim

NOTES

-

Tan, K. Y. L. (Ed.). (2005). Essays in Singapore legal history: An introduction. In K. Y. L. Tan. (Ed.), Essays in Singapore legal history (pp. 2, 41). Singapore: Marshall Cavendish Academic and the Singapore Academy of Law. Call no.: RSING 349.5957 ESS ↩

-

Supreme Court. (2010, May 21). Milestones in Singapore’s legal history. Retrieved from Supreme Court Singapore website. ↩

-

Singapore Academy of Law. (2006, November 30). Tracing the roots of our legal system. Retrieved from Singapore Academy of Law website. ↩

-

Chan, H. H. M. (1995). The legal system of Singapore (p. 6). Singapore: Butterworth Asia. Call no.: RSING 349.5957 CHA; Phang, A. B. L. (2005). The Reception of the English Law. In K. Y. L. Tan. (Ed.), Essays in Singapore legal history (p. 7). Singapore: Marshall Cavendish Academic and the Singapore Academy of Law. Call no.: RSING 349.5957 ESS. ↩

-

Braddell, R. St. J. (1915). The law of the Straits Settlements: A commentary. Singapore: Kelly & Walsh. Microfilm no.: NL 5723 ↩

-

Hickling, R. H. (1992). Essays in Singapore law (pp. 79–80). Petaling Jaya: Pelanduk Publications. Call no.: RSING 349.5957 HIC; Chan, 1995, pp. 4–5. ↩

-

Supreme Court, 21 May 2010. ↩