The Map That Opened Up Southeast Asia

Title: Exacta & Accurata Delineatio cum Orarum Maritimdrum tum etjam locorum terrestrium quae in Regionibus China, Cauchinchina, Camboja sive Champa, Syao, Malacca, Arracan & Pegu… (The True Depiction or Illustration of all the Coasts and Lands of China, Cochin China, Cambodia, Siam, Malacca, Arracan and Pegu, Likewise of all the Adjacent Islands, Large and Small, Together with the Cliffs, Riffs, Sands, Dry Parts and Shallows; All Taken from the Most Accurate Sea Charts and Rutters in Use by the Portuguese Pilots Today)

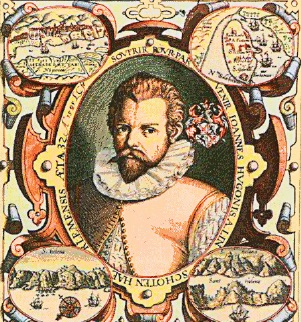

Creator: Jan Huygen van Linschoten (1563–1611)

Year published: 1596

Publisher: Cornelis Claesz (Amsterdam)

Language: Latin and Dutch

Type: Map; 39cm by 52cm

Call no.: RRARE 912.5 LIN

Accession no.: B26055964D

Donated by: Koh Seow Chuan (monochrome version)

The National Library has two different versions of the Exacta & Accurata map, both dated 1596: a black and-white copy donated by the philanthropist and architect Koh Seow Chuan, and this hand-coloured version in the David Parry Southeast Asian Map Collection. All rights reserved, National Library Board, Singapore.

The National Library has two different versions of the Exacta & Accurata map, both dated 1596: a black and-white copy donated by the philanthropist and architect Koh Seow Chuan, and this hand-coloured version in the David Parry Southeast Asian Map Collection. All rights reserved, National Library Board, Singapore.By the late 16th century, the Portuguese had dominated the trade to Southeast Asia for nearly a hundred years. Its monopoly depended on closely guarded knowledge about the best sailing routes to the region, known as the East Indies at the time.1

But a Dutchman called Jan Huygen van Linschoten changed the course of history for Singapore and Southeast Asia by deciphering the secrets of the Portuguese and sharing them with the world. Linschoten was the secretary to Don Frey Vicente de Fonseca, the Archbbishop of Goa, which was then under Portuguese rule. During his employment, Linschoten painstakingly made copies of archives that spelt out the closely guarded sailing directions.

Jan Huygen van Linschoten (1563–1611). Reproduced from Het Itinerario van Jan Huygen van Linschoten 1579-1592. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Jan Huygen van Linschoten (1563–1611). Reproduced from Het Itinerario van Jan Huygen van Linschoten 1579-1592. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.Combining this information with his own travel experiences and observations in Goa, Linschoten created Reysgheschrift vande navigatien der Portugaloysers in Orienten (Travel accounts of Portuguese navigation in the Orient), a maritime handbook published in 1595. The following year, he revealed even more of his hard-earned knowledge in a second, more detailed work: Itinerario, Voyage ofte Schipvaert van Jan Huygen van Linschoten naer Oost ofte Portugaels Indien, 1579–1592 (Travel Account of the Voyage of the Sailor Jan Huygen van Linschoten to the Portuguese East India).

The landmark Itinerario laid bare the Portuguese’s unrivalled information for navigating 16th-century Southeast Asia through the Melaka Straits. Aware that the Portuguese might not look favourably on outsiders who had gained access to their routes, Linschoten also included in it a recommendation to navigators to approach the region through the Sunda Straits in order to avoid Portuguese reprisal.2

The exposure of the Portuguese’s secrets ended their dominance in Southeast Asia. Two years later, in 1598, an English translation of the Itinerario was published in London. The release of the original work and the English edition launched a race between Dutch and English companies to claim the East Indies trade. This set the stage for Stamford Raffles’ arrival on Singapore’s shores more than two centuries later in 1819.

Exacta & Accurata provides detailed sailing instructions for the route to India via the Cape of Good Hope, and for negotiating the eastern coastlines of Asia. About the size of three and a half sheets of A4 paper, it was regarded as the standard reference map of the Far East until the 1630s, when Jan Jansson and William Blaeu, two Dutch map publishing houses, produced more maps of the region.

The map positions the islands from Sumatra in the west to Pupua, the early reference to Papua New Guinea, in the east with remarkable accuracy.3 Displaying a marvellous blend of contemporary Portuguese knowledge and mythical cartographic detail, it also depicts Japan in the shape of a lobster or shrimp, and Korea as an odd-shaped island.

China takes the form of a land of elephants and rhinoceroses, and is displayed with four large lakes in its interior on Luiz Jorge de Barbuda’s conception of the country as having a river system comprising several large lakes. Barbuda was a Portuguese cartographer who served Philip II of Spain from 1582.4

Interestingly, the map also shows a place called “Sincapura” on the southern tip of the Malay Peninsula. While the name alludes to the modern city of Singapore, scholars believe that the name and its variants, such as “C. Cinca Pula”, were used in European maps from the 1500s to the 1800s to denote either the town of Singapore, one of several straits on which Singapore is located, or the southern tip of the Malay Peninsula.5 Java on the map has an unknown south coast, and the shape of Celebes, or Sulawesi, is inaccurate.6

This detail, taken from the black-and-white version of the 1596 map, shows “Sincapura” on the southern tip of the Malay Peninsula. All rights reserved, National Library Board, Singapore.

This detail, taken from the black-and-white version of the 1596 map, shows “Sincapura” on the southern tip of the Malay Peninsula. All rights reserved, National Library Board, Singapore.Linschoten and Petrus Plancius, a Flemish astronomer, geographer and theologian who prepared the map, revealed how knowledgeable the Portuguese were of Southeast Asia in the early to mid-16th century due to their extensive maritime explorations and rigorous navigational charting of the area.

Plancius had composed the map using the navigational charts of Fernao Vaz Dourado, a Portuguese cartographer who spent most of his life in India, and the manuscript maps of Bartolomeu Lasso, a 16th-century Portuguese cosmographer to the King of Spain and a map-maker himself.7

This hand-coloured 1596 map is part of the National Library’s David Parry Southeast Asian Map Collection. The library also holds a 1596 black-and-white version of the same map donated by the philanthropist and architect Koh Seow Chuan, which is part of the collection named after him.

– Written by Irene Lim

NOTES

-

Parry, D.E. (2005). The cartography of the East Indian Islands = Insulae Indiae Orientalis (p. 83). London: Country Editions. Call no.: RSING q912.59 PAR ↩

-

Parry, 2005, pp. 84–85; Suarez, T. (1999). Early mapping of Southeast Asia (p. 177). Hong Kong: Periplus. Call no.: RSING q912.59 SUA ↩

-

Suarez, 1999, p. 179; Sanderus Maps. (2004–2015). Old antique map of Southeast Asia by Jan Huygen van Linschoten oriented to the East. Retrieved from Sanderus Antiquariaat website. ↩

-

Borschberg, P. (Ed.). (2004). Remapping the Straits of Singapore? New insights from old sources, In Iberians in the Singapore-Melaka Area (16th to 18th century) (p. 96). Wiesbaden: Harrossowitz; Lisboa: Fundacao Oriente. Call no.: RSING 959.50046 BOR ↩

-

Sanderus Maps, 2004–2015. ↩