Old-world Amusement Parks

Theme parks in Singapore had their heyday from the 1920s to 50s. Lim Tin Seng charts their glory days and subsequent decline.

Singapore’s first experience with the thrills and spills of an amusement park took place in 1922 when it held the Malaya-Borneo exhibition. The exhibition featured rides such as a Ferris wheel and carousel, an international trade fair, and exhibits of the flora and fauna of Malaya and Borneo. Arshak C. Galstaun Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Singapore’s first experience with the thrills and spills of an amusement park took place in 1922 when it held the Malaya-Borneo exhibition. The exhibition featured rides such as a Ferris wheel and carousel, an international trade fair, and exhibits of the flora and fauna of Malaya and Borneo. Arshak C. Galstaun Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.Built between the 1920s and 30s during the pre-television era, Singapore’s three amusement parks – New World, Great World and Gay World – provided a unique form of entertainment in colonial times. These “worlds” were permanent venues that provided an interesting East-meets-West blend of entertainment, with offerings as diverse as carnival rides, circus acts and boxing contests to Chinese opera and risqué cabaret shows.1

Rise of the “Worlds”

When New World, the first of the three parks, opened in 1923, the amusement park industry was already well established in the West (the concept likely originated in the religious festivals and trade fairs of medieval Europe). The World’s Columbian Exposition (also known as the Chicago World’s Fair), held in Chicago in 1893 to celebrate the 400th anniversary of the discovery of America by Christopher Columbus, is considered to be the first of its kind and included a separate amusement area distinct from the exhibition spaces. More than 26 million people from the world over visited the fair during its six-month run. It featured the world’s first Ferris wheel, a 260-ft (79-m) tall megastructure that could take 2,160 passengers.2

The amusement park came to be defined as a self-contained site featuring a hotchpotch of attractions, shows and carnival rides assembled for the express purpose of entertaining the masses. By the first quarter of the 20th century, amusement parks had begun to emerge in major Asian cities such as Shanghai and Beijing in China, and Tokyo and Osaka in Japan.3

Singapore’s first experience with the thrills and spills of an amusement park took place in 1922 when the colony held the Malaya-Borneo exhibition from 31 March to 17 April to showcase the economic achievements of British Malaya and Borneo as well as commemorate the visit of Edward, Prince of Wales, to Singapore. The exhibition was a massive endeavour; it took six months to set up and occupied a 68-acre (27-ha) site bordered by Telok Ayer Market, Mount Palmer, Anson Road, McCallum Street and the coastline. The site included a Ferris wheel and carousel, an international trade fair, and exhibits of the flora and fauna of Malaya and Borneo. There were also cinemas and a football pitch for matches as well as cultural performances and shows by various ethnic groups.4

Despite its size, the Malaya-Borneo exhibition was held for only three weeks. When it ended on 17 April, the exhibition was estimated to have attracted more than 300,000 visitors. Its resounding success inspired the Straits Chinese brothers and businessmen Ong Boon Tat and Ong Peng Hock to establish the New World amusement park along Jalan Besar.5 When the 6-acre (2-ha) park opened on 1 August 1923, The Straits Times reported that its attractions – which included a Ferris wheel, carousel and a football field – were laid out “in a style reminiscent of the Malaya-Borneo exhibition”.6 New World continued to expand after its opening and by the time it celebrated its 10th anniversary in 1933, it had a ghost train ride, a dodgem or bumper car enclosure and an open-air cinema. By then, New World had gained a reputation for its thrilling boxing contests, colourful opera performances and raucous cabaret shows.7

This photo, taken in the 1950s, shows the entrance of New World at Jalan Besar, the first of three amusement parks established in Singapore. It was opened on 1 August 1923 by brothers Ong Boon Tat and Ong Peng Hock. Singapore Chinese Clan Associations Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

This photo, taken in the 1950s, shows the entrance of New World at Jalan Besar, the first of three amusement parks established in Singapore. It was opened on 1 August 1923 by brothers Ong Boon Tat and Ong Peng Hock. Singapore Chinese Clan Associations Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.Great World, the second of the three “Worlds”, opened nearly a decade after New World on 1 June 1931. Situated on a 6.8-acre (2.7-ha) site bounded by Kim Seng, River Valley and Zion roads, the park was founded by Lee Choon Yung, a relative of philanthropist Lee Kong Chian. When Great World first opened, its attractions were mainly live shows and performances, including Shanghainese and Cantonese operas, Malay bangsawan theatre and a Western-style vaudeville act. Other attractions included a zoo, a coloured water fountain and open-air cinemas.8 In subsequent years, Great World expanded to include a British trade fair and a replica model of an ancient Chinese city complete with landscaped areas, waterfalls, temples, pagodas and even people dressed as Chinese peasants.9

Great World was opened on 1 June 1931 by Lee Choon Yung, a prominent Chinese banker and community leader. The amusement park was situated on a site bounded by Kim Seng, River Valley and Zion roads. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

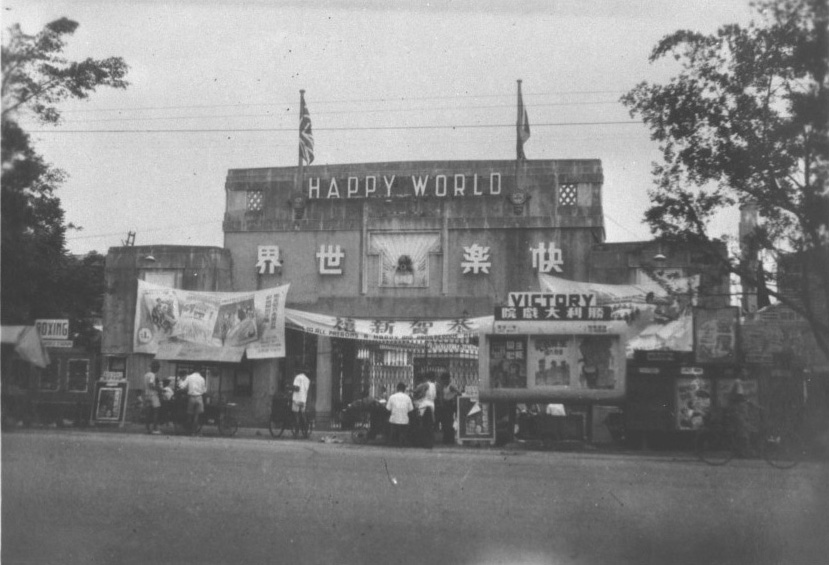

Great World was opened on 1 June 1931 by Lee Choon Yung, a prominent Chinese banker and community leader. The amusement park was situated on a site bounded by Kim Seng, River Valley and Zion roads. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.Happy World, the last of the three parks, opened on 6 May 1937 (and was known as such until it was renamed Gay World in 1964). Owned by George Lee Geok Eng, founder of the Nanyang Siang Pau Chinese newspaper, the new park was located on a 10-acre (4.5-ha) tract of land at the junction of Geylang Road and Mountbatten Road, and housed some impressive facilities. Its amenities included a 7,000-capacity covered stadium that hosted boxing matches and sports competitions; an oval-shaped cabaret hall that “set a new standard for Singapore”; theatres for Chinese, Malay and Indian shows; an open-air cinema with a seating capacity of 300; and some 300 stalls selling various goods and refreshments. The opening ceremony of Happy World was a lavish affair attended by some 1,000 guests who reportedly “consumed nearly 100 gallons of champagne”.10

Happy World, the last of the three “Worlds”, was opened on 6 May 1937 by George Lee Geok Eng, the founder of the Nanyang Siang Pau Chinese newspaper. The amusement park was renamed Gay World in 1964. R. Browne Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore

Happy World, the last of the three “Worlds”, was opened on 6 May 1937 by George Lee Geok Eng, the founder of the Nanyang Siang Pau Chinese newspaper. The amusement park was renamed Gay World in 1964. R. Browne Collection, courtesy of National Archives of SingaporeAlthough the three “Worlds” opened in different years, they shared many similar characteristics. First, all were established during the pre-television era – when owning a radio was still the preserve of the rich – and provided a convenient and affordable means of entertainment. The parks opened daily from 6 pm to midnight, and the entrance fee was priced at a reasonable 20 cents per person (with individual attractions ticketed separately).

Second, the parks were patronised by people of all ages, ethnic groups and social classes, united in their pursuit of fun and entertainment. On some nights, these parks could attract as many as 50,000 visitors. Festive occasions such as Lunar New Year, Hari Raya and Deepavali were grand events, often culminating in a spectacular fireworks display. The three amusement parks conjured up images of fun and gaiety as The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser newspaper aptly described in 1937:

“Follow the streams of cars purring east and west, the sweating rickshaw pullers… [and] the walking crowd… you eventually come to huge gate-ways. Electric words proclaim you are entering a “World” – a “Great” and a “New” world – a world bounded by high fencing, inside which can be found laughter and happiness and the comedies – and tragedies – of life…These huge playgrounds… patronised by Europeans, Eurasians, Chinese, Malay, Indians, Japanese and the rest of the racial conglomeration of Singapore, are products of the past twenty years. From scant and scraggy plots of ground… they have developed into lusty and strapping parade grounds of the rich and poor alike, where a Towkay may entertain twenty friends to dinner in the “million dollar” private apartment of the expensive restaurants… and where the humblest member of the working class may spend his very hard-earned fifty cents or more unostentatiously at the gaming booths, the open-air cinema, or the laneside hawkers.”11

A typical night at the Great World amusement park in 1962. Amusement parks were very popular with families and courting couples in the pre-television era. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

A typical night at the Great World amusement park in 1962. Amusement parks were very popular with families and courting couples in the pre-television era. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.A Thrilling World of Rides and Games

Taking a spin on the Ferris wheel, carousel, ghost train and the dodgem or bumper car was the main attraction for many. Considering this was the 1920s and 30s when the rickshaw was still the most common mode of transportation, these automated mechanical rides were seen as marvellous engineering feats. According to Richard Woon, who used to frequent Great World during the 1950s, each ride cost around 30 to 50 cents, with the ghost train being his favourite. The mini train would make its way through a darkened enclosure the size of a basketball court, passing through many closed doors that opened to reveal ghoulish surprises on the other side.

Theatre personality Margaret Chan, who spent many weekends at Great World when she was a child, preferred the carousel: “My little sister and I would rush for the one and only elephant on the carousel, and [we] loved sipping the free Milo… out of little conical cups.”12

The carousel ride at the Great World amusement park in 1954. Along with the Ferris wheel, ghost train and dodgem or bumper car, the carousel was one of the most sought-after rides at the amusement parks. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

The carousel ride at the Great World amusement park in 1954. Along with the Ferris wheel, ghost train and dodgem or bumper car, the carousel was one of the most sought-after rides at the amusement parks. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.In addition to the rides, there was also a wide variety of carnival games. These included ring toss, swinging cans and dart throwing. There were also gambling stalls called “tikam tikam” (Malay for game of chance) where people could bet on numbers to win either cash or prizes. Woon recalls that one of the most popular booths at Great World was the shooting gallery. The game required the player to shoot a target from various distances using a rifle to win prizes such as watches, bags, fans and vacuum flasks.13

As each carnival game cost at least $1 to play in the 1950s, they were considered expensive, and out of reach for most children and even some adults. Nonetheless, just watching those playing these games was entertainment enough. Alternatively, there were hawker stalls, coffee shops and sundry shops selling an eclectic mix of textiles, toys, sweets and medicinal products to patronise. Some of these stalls even put up demonstrations as sideshows to attract the crowds. All these attractions and amenities breathed life into the amusement parks and transformed them into glittering, heady places of unbridled fun for the people. Writer Felix Chia describes a typical night scene at Great World:

“Hundreds of multi-coloured bulbs blinked at us as we approach the gate… There is already a large crowd though it is only 7 o’clock in the evening. We are being stopped politely by an old Jew, who offers to sell us boot polish and shoelaces… As we look in the distance we see a Chinese medicine pedlar exerting himself in feats of strength, in apparent attempts to impress those who gather around him. And the energetic Indian snake-charmer is busy exciting his pet to twirl and curl above its basket, as the notes of his music shrill through the noisy air… we [also] hear the “om-pahpah” of the brass band coming quite distinctly from the enclosure of the Ferris Wheel, attracting the crowd to the thrill of riding with the night wind.”14

A Colourful World of Shows and Performances

When recounting the sights and sounds of Great World, Chia remembers the lure of traditional theatre like Malay bangsawan, wayang Peranakan (Peranakan theatre) and Chinese opera.15 In the pre-television era, such stage performances were one of the main forms of entertainment for the people.

When the amusement parks first opened, they tried to entice performers from their makeshift street theatres to proper stage venues at the parks, offering perks not usually extended to other tenants. For instance, rental fees for performance venues used by Chinese opera troupes were waived; to sweeten the deal they were rewarded with a daily or monthly remuneration and could even retain the earnings from the sale of tickets. In addition, the park owners made a conscious effort to construct performance stages that were customised to the needs of the opera troupes. New World, for example, had two venues for Peking opera – the teahouse-style Ba Jiao Ting (八脚亭; Octagon Pavilion) and the indoor Da Wu Tai (大舞台; Great Stage), another for Cantonese opera called Ri Guang Tai (日光台; Sunshine Stage), one for Teochew opera called Bai Lao Hui (百 老汇; Community Assembly or Broadway Hall), and yet another for Hokkien opera. Similarly, Great World had two stages – Xiao Guang Han (小广寒; Little Winter Space) for Peking opera and Guang Dong Xi Yuan (广东戏院; Guangdong Theatre) for Cantonese opera.16

Traditional theatrical performances such as bangsawan (Malay opera), wayang Peranakan (Peranakan theatre) and Chinese opera (pictured here) were performed to near-capacity crowds at the amusement parks. Donald Moore Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Traditional theatrical performances such as bangsawan (Malay opera), wayang Peranakan (Peranakan theatre) and Chinese opera (pictured here) were performed to near-capacity crowds at the amusement parks. Donald Moore Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.These incentives enabled the parks to attract the best opera troupes, such as the Teochew troupe Lau Sai Thor Guan and its Hokkien counterpart, Sin Sai Hong, and also non-Chinese troupes like the popular Dean’s Opera troupe, run by the bangsawan star Khairuddin, and the Peranakan theatre group Oleh Oleh Party. Over time, the amusement parks became synonymous with specific operatic genres.For instance, Cantonese and Hainanese operas usually performed at Great World and New World, while Teochew and Hokkien opera troupes staged their shows at Gay World.17 Peranakan plays were performed at Gay World Stadium and Twilight Hall in New World, while bangsawan theatre was staged at all three parks.18 In those days, entrance tickets cost between 10 cents and $3. However, those who could not afford tickets could still catch snippets of the show through the open doors or listen to the music from the outside.19

Those who preferred Western fare could watch the latest films from Hollywood. New World had three cinemas – Pacific, State and Grand – while Great World had four – Sky, Globe, Canton and Atlantic. Eng Wah’s first three cinemas – Victory, Silver City and Gay – all had their beginnings in Gay World. The first films that were screened in the parks were from the silent era. But as the film industry developed, cinemas began screening “talkies” or sound films. The post-war period saw the golden age of the Malay film industry in Singapore with Cathay-Keris and Shaw Brothers as the two major players. Cinemas began screening locally produced Malay films along with Chinese imports from Hong Kong. Shaw Brothers, sensing a business opportunity, became the eventual proprietors of New World and Great World.20

The crowd visiting the booths at a trade exhibition at Happy World in 1953 (renamed in 1964 as Gay World). The three amusement parks were popular venues for large trade fairs and exhibitions due to their generous expanse of space. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

The crowd visiting the booths at a trade exhibition at Happy World in 1953 (renamed in 1964 as Gay World). The three amusement parks were popular venues for large trade fairs and exhibitions due to their generous expanse of space. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.Another attraction were the getai (歌台) shows. Literally translated as “song stage”, getai are live stage performances of popular song, dance and dramatic acts. Getai is believed to have originated during the Japanese Occupation (1942–45) when New World set up the first getai troupe called Da Ye Hui (大夜会). Comprising a five-member band and two singers, Da Ye Hui performed a repertoire of traditional Chinese songs every night. There was no admission fee for these shows and patrons were only required to pay for their drinks.21

After the war, getai became a mainstay of the amusement parts. At its peak in the 1950s, there were more than 20 getai venues altogether in the three parks.22 Typically, a getai consisted of a stage with a fabric backdrop and a viewing area that could accommodate 60 square, wooden tables that could seat four patrons each. There was no allocated seating, and patrons who did not arrive early enough to reserve seats before the show began at 8 pm risked having to stand throughout the night. Audience members were also given slips on which they could request for a song by their favourite vocalist. The shows were wildly popular, attracting as many as 500 patrons a night, and up to 1,000 when business was good.23

As getai gained popularity, its repertoire was expanded to include folk dances, comedy sketches, drama skits and crosstalk (相声) performances. To attract the menfolk, striptease acts were added to the repertoire. New World’s Fong Fong Café broke new ground by staging a skit titled “Artist’s Model” in 1951. Based on a 1930 act by Chinese playwright Xiong Fo Xi (熊佛西), the skit featured a model undressing as she prepared to pose for a figure-drawing session. After its second performance two years later in 1953, other getai groups became emboldened enough to introduce similar raunchy acts. For the next few years striptease shows became the main attraction at these parks until the government had a change of heart and launched an “anti-yellow” campaign in 1959 to snuff out activities it considered as promoting a morally corrupt lifestyle.24

Sports events were another attraction at the amusement parks. The most popular were wrestling fights featuring favourites such as King Kong (alias Emile Czaya) and Ho Wah Peng, and boxing matches involving greats like Felix Boy (alias S. Sinnah).25 These matches were held in purpose-built stadiums, including Gay World’s 7,000-capacity covered stadium, which also served as the venue for the 1952 Thomas Cup badminton tournament and the basketball matches of the 7th Southeast Asian Peninsular Games in 1973.26

Apart from hosting trade fairs and industrial exhibitions, the amusement parks also entertained visitors with a motley assortment of sideshows such as strongman acts by Mat Tarzan (also known as “Tarzan of Malaya”), juggling and acrobatics performances, miniature zoos and beauty contests like “Miss Trade Fair”.27

A Glittering World of Dance and Cabarets

“I went into the dancing-hall. There was an excellent orchestra, hired, I think… It was playing ‘Auf Wiedersehen’ when I came in, and crowd of dancers, mostly young Chinese – the men in white European clothes with black patent-leather dancing shoes, the girls in their semi-European dresses slit at the side – filled the dancing floor. When the dance was over, I noticed a number of girls who left their partners as soon as the music stopped and went to join other girls in a sort of pen. They were the professional Chinese dancers who can be hired for a few cents a dance.”28

This was the scene in the cabaret hall at New World as described by former British intelligence officer and journalist Bruce Lockhart in 1936. Each amusement park had its own cabaret complete with dance halls, big bands and cabaret girls, or taxi-dancers as they called them, because patrons could hire these girls for a dance by purchasing a ticket.29

The first cabaret opened in New World in December 1929, and featured a glittering show led by a company of some 30 cabaret girls and vaudeville artistes. They were considered “the cream of Manila” and personally handpicked by the park’s co-founder Ong Peng Hock. As cabarets became more popular following the opening of Great World and Gay World, the park owners began recruiting cabaret girls from different ethnic groups and from cities such as Hong Kong and Shanghai to cater to a wider customer base. Local Chinese businessmen for instance preferred Chinese dance hostesses, while the British and other non-Chinese customers made a beeline for the Eurasian girls because they could speak English. The alcohol-fuelled cabarets were patronised by all segments of society but invariably only the towkays (businessmen) and the wealthy could afford to hire the girls.30

A 1945 photograph of a cabaret performance at the Great World amusement park. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

A 1945 photograph of a cabaret performance at the Great World amusement park. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.To hire these comely girls for dances, patrons had to buy a booklet of coupons, which were priced in the 1940s at a dollar each for a set of three dances in New World and Great World, and four dances in Happy World. This was in addition to the entrance fee of between 50 cents and a dollar, and their mandatory drinks. To engage the services of the more popular girls whose dance cards were perpetually filled, patrons had to pay a “booking” fee of $13 that would entitle them to a one-hour dance with a hostess. The fee also included a date with the hostess after the cabaret had closed, and it is very likely that some of the more enterprising girls would trade sexual favours on the side.

At the end of each night, the hostesses would cash in the dance coupons they had collected. The more popular girls would be allowed to keep their entire coupon earnings, while others retained 40 percent, with the remainder going to the cabaret owner. The girls were also paid a fixed monthly salary of $25.31

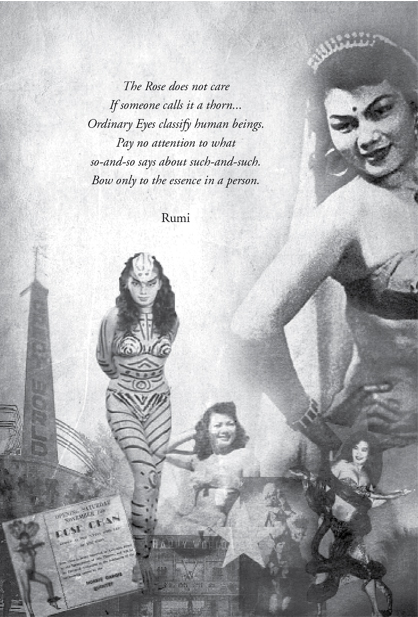

One of the most well-known personalities in the cabaret scene was Rose Chan, who joined Happy World cabaret as a dance hostess in 1942. An accomplished dancer and a former beauty queen, Chan quickly rose to fame. By 1951, the brassy Chan had her own dance company – the Rose Chan Revue – which saw her touring Malaya and Singapore, bending iron bars with her neck, inviting a motorcycle to run over planks placed across her body, and wrestling with a slithering python. Her most notable shows, however, were her striptease acts that were often performed to sold-out houses.32

The riveting story of the stripper Rose Chan, who found fame at the Happy World cabaret in the 1940s and 50s is documented in the book No Bed of Roses: The Rose Chan Story. Pictured here is the frontispiece of the book. All rights reserved, Rajendra, C. (2013). No Bed of Roses: The Rose Chan Story. Singapore: Marshall Cavendish.

The riveting story of the stripper Rose Chan, who found fame at the Happy World cabaret in the 1940s and 50s is documented in the book No Bed of Roses: The Rose Chan Story. Pictured here is the frontispiece of the book. All rights reserved, Rajendra, C. (2013). No Bed of Roses: The Rose Chan Story. Singapore: Marshall Cavendish.However, most of the cabaret girls did not share the same luck (and gumption) as Chan. Many came from impoverished and broken families, and were forced to join the cabaret to earn a living. To make matters worse, the girls were frequently subjected to harassment by inebriated customers on the dance floor, and had to fend off men who tried to touch them inappropriately or kiss them while dancing.33

While the cabaret girls were a key attraction at the dance halls, there were those who came solely for the purpose of dancing. The dance halls were impressive and considered huge at the time. For instance, Gay World’s oval-shaped hall – skirted by marbled columns and bordered by a three-tiered dining area – had a dance floor that could accommodate up to 300 couples. New World’s dance hall was airconditioned and its octagonal dance floor could take more than 1,200 people; its star attraction was a stage that could rise and revolve.34

The dance halls also featured their own resident bands, with fancy names like American Dance Band and D’Souza’s Famous Band playing tunes from “peppy, snappy and real hot” to “sweet, swingy and rhythmic” to accompany dancers doing the waltz, foxtrot, quickstep, tango and the rhumba. Special events were also regularly held at the cabarets, including song and band championships, dance competitions and the Annual Malaya Kebaya Queen Competition.35

Decline of the “Worlds”

The popularity of amusement parks began to wane towards the end of the 1960s. The death blow came from the advent of television but there were other contributing factors like the proliferation of shopping malls, bowling alleys, roller skating rinks, public swimming pools, and attractions such as the zoo and bird park. Amusement parks were forced to shutter many of their attractions, leaving only the cinemas and restaurants open. Although Gay World tried to reinvent itself by setting up a shopping emporium within its grounds, it came a little too late. The New Nation reported in 1976:

“Today, the Worlds are not what they used to be… By night, it is ghostly and deserted, pitch-black except for oases of activity like the cinemas and the penny arcade. By day, office workers traverse its grounds to reach lunchtime places in buildings nearby. The amusement machines… stand as monument to better times. Some are coated with rust and are slowly falling apart. Grass sprouts from the tracks of the miniature train.”36

Without the heaving crowds, the amusement parks were unable to survive and eventually closed. Gay World was the last park to cease operations in 2000.37 Over the years, the land occupied by the parks has been taken over by commercial or residential buildings. Only the faded memories of older Singaporeans linger, recalling the once glorious past of these “Worlds” and the joy and laughter they brought to their lives.

New World

1923: Opens on 1 August.

1929: Establishes Singapore’s first cabaret.

1938: Shaw Brothers acquires New World.

1942: Remains open during the Japanese Occupation.

1987: City Developments buys over New World.

2009: Site is redeveloped into the first eco-friendly mall called City Square Mall.

Great World

1931: Opens on 1 June.

1940: Shaw Brothers acquires Great World.

1942: Remains open during the Japanese Occupation.

1964: Ceases operations but its cinemas and restaurants remain open.

1979: Malaysia’s Sugar King Robert Kuok buys over Great World.

1997: Site is redeveloped into a residential-commercial project called Great World City.

Gay World

1937: Opens as Happy World on 6 May.

1942: Remains open during the Japanese Occupation.

1952: Its indoor stadium is used as a venue for the Thomas Cup.

1964: Renamed Gay World and transferred to the British and Malayan Trustees Ltd.

1973: Used as a venue for the 7th Southeast Asian Peninsular Games.

2000: Tenants are given notice by the Land Office to move from the park in March; main tenant Eng Wah Organisation terminates its lease.

2001: Demolished and the unoccupied site is zoned for residential projects.

City Square Mall, Singapore’s first eco-friendly mall, was launched in 2009. The mall stands on the site of the former New World amusement park along Jalan Besar. New World was the first of the three amusement parks to open. Courtesy of City Developments Limited.

City Square Mall, Singapore’s first eco-friendly mall, was launched in 2009. The mall stands on the site of the former New World amusement park along Jalan Besar. New World was the first of the three amusement parks to open. Courtesy of City Developments Limited.

A photo of the exterior of Great World City taken during its official opening in 1997. This mixed-use development comprising retail, office and residential units occupies the site of the former Great World amusement park. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

A photo of the exterior of Great World City taken during its official opening in 1997. This mixed-use development comprising retail, office and residential units occupies the site of the former Great World amusement park. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore. Lim Tin Seng is a Librarian with the National Library, Singapore. He is the co-editor of Roots: Tracing Family Histories – A Resource Guide (2013); Harmony and Development: ASEAN-China Relations (2009) and China’s New Social Policy: Initiatives for a Harmonious Society (2010). He is also a regular contributor to BiblioAsia.

Lim Tin Seng is a Librarian with the National Library, Singapore. He is the co-editor of Roots: Tracing Family Histories – A Resource Guide (2013); Harmony and Development: ASEAN-China Relations (2009) and China’s New Social Policy: Initiatives for a Harmonious Society (2010). He is also a regular contributor to BiblioAsia.

NOTES

-

Chandy, G. (1980, April 28). Worlds of days gone by. New Nation, p. 9. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Chicago Historical Society. (1999). The World’s Columbian Exposition. Retrieved from Chicago Historical Society website; Maranzani, B. (2013, May 1). 7 things you may not know about the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair. Retrieved from History.com website. ↩

-

Milman, A. (2008). Theme park tourism and management strategy. In A.G. Woodside & D. Martin. (Eds.), Tourism management: Analysis, behaviour and strategy (pp. 219–220). Wallingford, UK; Cambridge, MA: CABI. (Call no.: RBUS 338.4791 TOU); Mohun, A.P. (2013). Amusement parks for the world: The export of American technology and know-how, 1900–1939. Icon, 19, 100–112, p. 102. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website; Dong, M.Y., & Bender, T. (2003). Republican Beijing: The city and its histories (pp. 199–205). Berkeley: University of California Press. (Call no.: R 951.15604 DON) ↩

-

Anak Singapura. (1935, September 19). Notes of the day: Malaya-Borneo. The Straits Times, p. 10; Malaya-Borneo exhibition. (1922, January 5). The Straits Times, p. 9; Prince views Malaya’s wealth. (1922, April 1). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser (1884–1942), p. 14. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Malaya-Borneo: Closing scene at the great exhibition. (1922, April 18). The Straits Times, p. 9. Retrieved from NewspaperSG; Holden, P. (2004). At home in the worlds. In R. Bishop, et. al. (Eds.), Beyond description: Singapore space historicity (p. 87). London: Routledge. (Call no.: RSING 307.1216095957 BEY) ↩

-

New entertainment centre. (1923, August 2). The Straits Times, p. 10. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The Straits Times, 2 Aug 1923, p. 10; Development of the New World. (1935, October 8). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser (1884–1942), p. 23. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Page 7 advertisements column 1: The Great World Show. (1931, June 1). The Straits Times, p. 7. Retrieved from NewspaperSG; National Archives of Singapore. (c1950). View of entrance to Great World Amusement Park,1950s [Image of Photograph]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website; Tong, K. (1997, October 11). Great World. The Straits Times, p. 4. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Getting ready for trade fair. (1933, May 12). The Straits Times, p. 12; Great World’s fifth anniversary. (1936, July 29). The Straits Times, p. 12. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

National Archives of Singapore, 1950; Yong, C.F. (1992). Chinese leadership and power in colonial Singapore (p. 309). Singapore: Times Academic Press. (Call no.: RSING 959.5702 YON); Opening of Happy World. (1937, May 7). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser (1884–1942), p. 9. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

When three parks ruled Singapore’s night life. (1990, March 25). The Straits Times, p. 2; Singapore’s new playground. (1937, April 27). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser (1884–1942), p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Chan, K.S. (2000, June 12). Worlds of fun and games. The Straits Times, p. 7. Retrieved from NewspaperSG; Sng, S. (Interviewer)(2005, January 26). Oral history interview with Richard Woon Kai Yin [MP3 recording no. 002908/71/03]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website; The Straits Times, 25 Mar 1990, p. 2. ↩

-

Oral history interview with Richard Woon Kai Yin , 26 Jan 2005; Rudolph, J. (1996). Amusement in the three “worlds”. In S. Krishnan, et. al. (Eds.), Looking at culture (p. 22). Singapore: Artres Design & Communications. (Call no.: RSING 306.095957 LOO) ↩

-

Oral history interview with Richard Woon Kai Yin , 26 Jan 2005; Rudolph, 1996, p. 22. ↩

-

Lee, T.S. (2009). Chinese street opera in Singapore (pp. 32–35, 183–192). Urbana: University of Illinois Press. (Call no.: R 782.1095957 LEE) ↩

-

Shaw Organisation. (2007). Amusement parks: Great World and New World. Retrieved from Shaw Theatres website; Yong, C.F. (2013). Tan Kah-Kee: The making of an overseas Chinese legend (p. 211). Singapore: World Scientific. (Call no.: RSING 338.04092 YON); Lee, 2009, p. 34; Yung, S.S. (2008). The Shaw Brothers in Southeast Asia. In P. Fu (Ed.), China forever: The Shaw Brothers and diasporic cinema (p. 143). Urbana: University of Illinois Press. (Call no.: R 791.43095125 CHI) ↩

-

Tan, S.B. (1993). Bangsawan: A social and stylistic history of popular Malay opera (p. 30). Singapore: Oxford University Press. (Call no.: R 782.109595 TAN) ↩

-

Ho, H.L. (2014). The 1950s striptease debates in Singapore: Getai and the politics of culture (pp. 15– 18). [Unpublished master’s thesis, National University of Singapore]. Retrieved from National University of Singapore ScholarBank@NUS website. ↩

-

金人 [Jin Ren]. (1993, November 28). 五十年代歌台点 滴. 联合早报 [Lianhe Zaobao], p. 50; 别忘了另一段歌台 历史. (2007, October 20). 联合早报 [Lianhe Zaobao], p. 25. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Fu, H. (1953, February 26). Pretty girls, songs, dance and comedy. The Singapore Free Press, p. 8. Retrieved from NewspaperSG; Ho, 2014, p. 20. ↩

-

Ho, 2014, pp. 17–18, 35–37, 120; The Straits Times, 25 Mar 1990, p. 2. ↩

-

The Straits Times, 12 Jun 2000, p. 7; De Souza, A. (1998, July 16). Of fights and sweaty diners. The Straits Times, p. 29. Retrieved from NewspaperSG; Shaw Organisation, 2007; National Heritage Board. (2006). Jalan Besar: A heritage trail (p. 12). Singapore: National Heritage Board. (Call no.: RSING 959.57 JAL) ↩

-

Leong, W.K. (2000, May 20). The last days of Gay World. The Straits Times, p. 69. Retrieved from NewspaperSG; The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser (1884–1942), 27 Apr 1937, p. 1; Happy World is chosen. (1952, February 8). The Straits Times, p. 7; Gay World Stadium gets $22,000 face-lift for Seap basketball matches. (1973, July 29). The Straits Times, p. 6. Retrieved from NewspaperSG ↩

-

Shaw Organisation, 2007; Return of Mat Tarzan. (1993, January 12). The Straits Times, p. 12. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Lockhart, R.H.B. (1936). Return to Malaya (p. 143). London: Putnam. (Call no.: RCLOS 959.5 LOC) ↩

-

Shaw Organisation, 2007. ↩

-

The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser,(1884–1942), 8 Oct 1935, p. 23; New Nation, 28 Apr 1980, p. 9; Shaw Organisation, 2007. ↩

-

Shaw Organisation, 2007; Rudolph, 1996, pp. 25–26; Memories of another day. (1984, March 8). Singapore Monitor, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Rajendra, C. (2013). No bed of roses: The Rose Chan story (pp. 240–241). Singapore: Marshall Cavendish Editions. (Call no.: RCLOS 792.7028092 RAJ); Ho, 2014, p. 38 ↩

-

Rudolph, 1996, pp. 26–27; Phan, M.Y. (1995, June 9). Three worlds and a time when life was a cabaret. The Straits Times, p. 8. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser (1884–1942), 7 May 1937, p. 9; Singapore’s latest cabaret. (1938, May 15). The Straits Times, p. 3. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Great to be back in a whole new world. (1996, April 18). The Straits Times, p. 2; Heng, G. (1976, July 13). Oh, so many worlds apart!. New Nation, pp. 10–11. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The Straits Times, 20 May 2000, p. 69. ↩