Public Housing, Private Lives

Incredibly, people living in some of the first one-room flats had to share their toilets and kitchens with strangers. Yu-Mei Balasingamchow tells you how far public housing has come since 1960.

New flat dwellers waiting for then Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew during his constituency tours of Tiong Bahru, Delta and Havelock housing estates in 1963. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

New flat dwellers waiting for then Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew during his constituency tours of Tiong Bahru, Delta and Havelock housing estates in 1963. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.I moved into a Housing and Development Board (HDB) flat for the first time in the late 1990s. It was a 10-year-old flat in a cosy estate in the east – nice and windy, receiving hardly any afternoon sun and within walking distance of an MRT station. Perhaps, most remarkably, from the common corridor outside my front door on the 11th floor, I had a partially unblocked view of the surroundings, which consisted mostly of low-rise buildings all the way to the sea, a glimmering slate-blue strip on the far horizon.

In the 17 years since, I’ve lived in five different HDB flats – all of which are or were older than that first one. Over years of viewing countless HDB flats of varying vintages, whether visiting friends or as a prospective tenant or buyer, I’ve often wondered what it is about the design and architecture of a flat that makes it feel welcoming and home-like.

I’ve also wondered about the social and environmental impact of high-rise living in an increasingly crowded island. Over one generation, from the 1960s to the 90s, we have been uprooted from homes mostly in or near the city centre and the Singapore River, and scattered all over a rapidly urbanised island. We have been transformed from a people who lived in low-rise dwellings close to the land, organised in what urban development specialist Charles Goldblum termed a “relatively traditional Asian habitat”, to a people who live in cookie-cutter and unapologetically modernist public housing, perfectly at ease with the idea of living 15, 20 or more storeys in the air.1 Almost everyone moves house at least once in their lives; everyone knows how to use a lift and a rubbish chute; everyone is used to looking down at the tallest trees in the neighbourhood.

We are not alone. Hong Kong and major cities in South Korea and China have become just as densely packed with residential high-rises in the last few decades, if not more so than Singapore, while other cities across Asia and North America are sprouting residential skyscrapers in the same vein. Yet as psychologist Robert Gifford notes, “given the age of our species, living more than a few storeys up is a very recent phenomenon”.2

Human beings have been clustering within urban settlements since the Neolithic Revolution about 12,500 years ago, but while we have been building massive monuments and landmarks for over a millennia, it is only in the last century or so that we have been living en masse in buildings taller than five storeys. Sociologists, psychologists, architects and urbanists are still mulling over the long-term implications of this phenomenon, which range from the behavioural and the political to the philosophical.

Building Fast and Furious: 1960–1965

In Singapore, high-rise residential housing took off when the HDB was formed on 1 February 1960 to replace the Singapore Improvement Trust (SIT), its colonial-era predecessor in charge of public housing. The HDB acted quickly to address the severe housing shortage: the oft-cited, hoary statistic is that within the first three years of its formation, the HDB had constructed 21,232 units – “just shy of the 23,019 units that SIT had managed in its 32 years of operations.”3 By the end of 1965, HDB’s first five-year building programme saw the completion of 53,000 new flats, 3,000 more than its intended target.

Academic literature aside, people today tend to forget that HDB’s apparent success during this period was in no small part due to its pragmatic focus on building “emergency” one-room flats, intended for rental only. As the nomenclature suggests, these were single-room units; toilet and kitchen facilities were sometimes communal. Imagine men and women from each floor sharing the same two toilets, or Chinese and Malay housewives cooking in the same communal kitchens. Difficult to imagine today, but this was the reality at the time, according to former HDB architect Alan Choe in an oral history interview with the National Archives of Singapore in 1997.4

(Left) Typical 1960s block plan and floorplan of a one-room (Improved) HDB flat with a floor area of 32.8 sq m.

(Left) Typical 1960s block plan and floorplan of a one-room (Improved) HDB flat with a floor area of 32.8 sq m.Such flats were poorly lit and cramped, but also relatively easy and inexpensive to build – an important consideration at a time when housing was urgently needed for low-income families suddenly displaced by fire or floods. As Choe recalls:

“One-room apartments in those days were really basic. Today, they would be our slums… But that is how we started the public housing to achieve the target numbers. Because in those days target numbers were a more important priority than the niceties that we can afford today…”5

HDB’s first five-year building programme also produced two- and three-room rental flats. These were distributed along a single corridor in blocks that were between five and 12 storeys tall. Although today we tend to think of the HDB “common corridor” as serving only one row of flats and looking out into open space, those early flats often contained a row of one- or two-room f/lats along both sides of the corridor. Although more economical to build, such corridors were poorly ventilated, received little natural lighting, and trapped or magnified noise.6

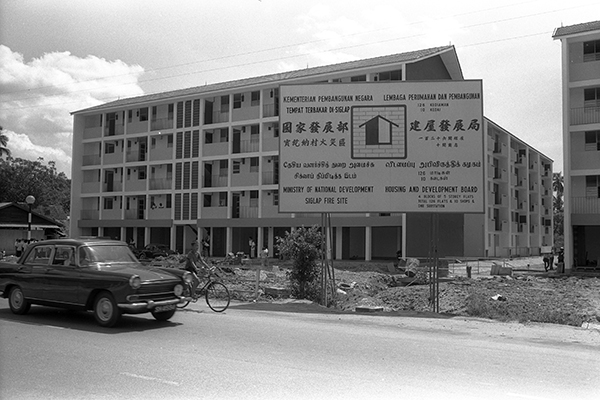

In 2008, I moved into a two-room HDB flat in a cluster of five-storey blocks at Siglap, just opposite Siglap Centre, the site of the former Siglap Market. The flats were built in 1963 to house residents of a kampong on the same site that had been razed by fire. There were shops on the ground floor and a single staircase in each block (with no lifts). About one-third of the units were HDB rental flats; the rest were occupied by a mix of longtime residents, who couldn’t imagine living anywhere else, and newcomers like me.

Newly erected two-room flats opposite Siglap Centre, the site of the former Siglap Market. The flats were built in 1963 to house residents of a kampong on the same site that had been razed by fire. The cluster of five blocks will be demolished soon to make way for a new housing project. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Newly erected two-room flats opposite Siglap Centre, the site of the former Siglap Market. The flats were built in 1963 to house residents of a kampong on the same site that had been razed by fire. The cluster of five blocks will be demolished soon to make way for a new housing project. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.Some of my friends were surprised that I had decided to rent such a small and barely renovated flat. I was simply charmed by the flat’s privacy (it was a top-floor corner unit), its view overlooking the neighbourhood buzz at the corner of East Coast Road and Siglap Road, and its classic fixtures like decorative metal window grilles and the original timber-framed front door with recessed rectangle panels.

Moreover, it was a cosy neighbourhood, with only four blocks of five storeys each, and on a comforting human scale – a characteristic of first-generation HDB estates, which were often sited close to the city centre on whatever limited plots of land were available, not yet in sprawling new towns. Even the inconvenience of climbing up and down five floors to get to my flat made real, in terms of physical experience, the fact of high-rise living.

True, by 21st-century standards the flat seemed small (it measured just 41 sq m). But I was just one person; many accounts from the 1960s tell of large families moving into such flats or smaller, along with the possessions they had accumulated in more spacious kampong houses or shophouses.

Conceptually, of course, HDB residents in the 1960s had to make far greater adjustments to the new-fangled features of flat living. As Choe said in his interview, “In the past you lived in your own ground, you build your attap hut, you have grounds around, you grow your chickens, you grow everything. Suddenly you are put into a pigeonhole, one-room apartment, two-room apartment.”7

Choe described new flat-dwellers who didn’t know at first how to unlock their Naco window louvres and complained to HDB that these were faulty. Those used to living in a kampong had to learn new habits for dressing casually at home (since strangers might walk past the corridor and see the occupants in various stages of undress) or buying food at the market (instead of growing their own food). Still others told of residents who brought pigs and poultry from their kampong to their new flats, even teaching the bewildered animals to climb the stairs. There were also stories of elderly people who lived on higher floors and felt “trapped” in their flats as they dared not use the lifts for fear of breakdowns.8

Kampong folks in the early 1960s loading their belongings onto a lorry and preparing for their move to high-rise living in HDB flats. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Kampong folks in the early 1960s loading their belongings onto a lorry and preparing for their move to high-rise living in HDB flats. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.Ultimately, the people who moved into HDB flats in the early 1960s – especially those who were resettled against their will – were often being uprooted from the only means of livelihood, lifestyle and community that they had ever known. Over half a century later, one cannot fully discount the psychological and social disruption they must have experienced during the transition. That world seems all the more distant since the surviving blocks of one-room and two-room flats are not easy to spot today – obscured, overshadowed and outnumbered as they are by younger, larger and more attractive blocks. Many have been demolished and indeed, the flats at Siglap where I used to live will be razed this year to make way for a new housing project.

HDB as a Way of Life: 1965–1975

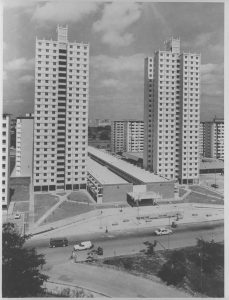

Although the HDB continued to build one-room and two-room rental flats until 1982, its priorities clearly shifted from the mid-1960s onwards “from speed and expediency to amenity and quality”, as stated in its 1966 annual report.9 Since the housing shortage had been resolved, HDB could focus on building larger flats with better designs in more optimally planned housing estates. The late 1960s to the 70s thus saw the emergence of not only a much wider range of flats to cater to people of different economic levels and household sizes, but also distinctive architecture such as the “point block” design which, at 20 and later 25 storeys, towered over the old rectangular “slab blocks”.

The first HDB “point blocks” – at 20 or 25 storeys high – were built in the late 1960s. In this photo taken at Bendemeer Road in the late 1960s, the “point blocks” tower over the surrounding rectangular “slab blocks”. In between the point blocks is a row of low-rise shops. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

The first HDB “point blocks” – at 20 or 25 storeys high – were built in the late 1960s. In this photo taken at Bendemeer Road in the late 1960s, the “point blocks” tower over the surrounding rectangular “slab blocks”. In between the point blocks is a row of low-rise shops. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.As it experimented with new designs, the HDB was shifting to not only “build for shelter” but “build for good architecture”, in the words of its former chief executive officer Liu Thai Ker.10 When Liu first joined the HDB in 1969 as head of its new research and design section, he found that there were no design, building or planning guidelines to govern such things as how far one HDB block should be from another, how many flats should be built in each block or neighbourhood (thus determining the density of the estate), or the mix of residential, commercial and industrial facilities in each estate.

Even the room sizes and designs of the early one-, two- and three-room flats were not strictly uniform. Flats sometimes contained awkward L-shaped rooms or long corridors, which residents complained were a waste of space. There were rooms or toilets that didn’t ventilate directly into the exterior of the flat, which made the living environment less than salubrious.

Liu and his colleagues at HDB developed new guidelines to standardise the building types, floor spaces, the number of rooms within each flat as well as room sizes. They also applied principles of building science to address the practical realities of living in the tropics, taking into consideration the prevailing winds, angle of the sun, and various types of sun hoods and window hoods that could be built to shield the flats from the tropical heat. As Liu said in an oral history interview with the National Archives of Singapore in 1996, “You cannot cut off everything – like morning sun and late afternoon sun, we have to accept. We [can] cut out the sun during the day, when it’s very hot.”11

Similarly, HDB architects studied how windows and roofs could be redesigned so that residents would not have to close all their windows when it rained. The latter was absolutely necessary in early HDB flats because the rain would enter and wet the flat interior (this used to happen in the kitchen of my Siglap flat). However, if all the windows were shut, the flats became stuffy and claustrophobic, particularly during the monsoon season when it pours heavily for hours on end.

HDB engineers found that if the rainwater ran uninterrupted off the roof, it would fall to the ground “like a bedsheet”, as Liu described it, and this large “sheet” of water would be sucked through an open window.12 However, if the rainwater first fell from the roof onto an inclined plane, it would break up into water droplets and then fall to the ground like scattered raindrops. These were less likely to be sucked through open windows, allowing residents to leave their windows open for ventilation when it rained.

Another perennial consideration in HDB planning was (and still is) how to have an estate layout that is attractive and interesting, without exposing flats to the full intensity of the afternoon sun. The typical guiding principle is to orientate the building towards north-south, but as Liu pointed out, “Of course you cannot have 100 percent [of flats] facing north-south. You have a certain percentage facing east-west.”13 The question of how to mitigate the latter came to be incorporated into HDB’s building plans; for example, low-rise blocks might be built along an east-west orientation, but would be shaded by trees or taller blocks to limit their exposure to the rising and setting sun.

As Singapore modernised and HDB estates became larger and more complex, the human factors that affect comfort and liveability also came to bear. By 1983, for example, Liu wrote that HDB’s approach to environmental design and building orientation was sensitive not only to the angle of the sun and the wind direction, but also to the impact of external traffic noise. He described how high-rise buildings were shielded from road noise by locating low-rise buildings in front of them; the low-rise blocks in turn were shielded by “earth mounds” facing the road.14

Having low-rise buildings in a densely inhabited estate served another important function: to maintain a sense of human scale in the built environment. Liu added that while most HDB blocks ranged from nine to 13 storeys in height, every precinct would also have some two- to four-storey blocks. Although he did not articulate it as such, there seems to have been an awareness that while Singaporeans had become accustomed to living in high-rise blocks, the environment would nonetheless benefit from having building heights that conformed more closely to human proportions.

A mix of low-rise and high-rise HDB flats in Toa Payoh, with a playground in the foreground, likely photographed in the late 1960s. Interspersing buildings of different heights helped to maintain a sense of human scale in the environment. Courtesy of the National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board.

A mix of low-rise and high-rise HDB flats in Toa Payoh, with a playground in the foreground, likely photographed in the late 1960s. Interspersing buildings of different heights helped to maintain a sense of human scale in the environment. Courtesy of the National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board.This is the sort of thinking that has since become familiar in the work of architect Jan Gehl and others like him. They argue that having a sense of human scale in the urban environment is precisely what draws people to engage and participate in public and community life, and develop emotional connections to a place.

In spite of the most well-intentioned building or planning guidelines of the time, not every HDB flat or estate could be built to optimise this contemporary notion of urban liveability. I count myself lucky that I’ve had the opportunity to live in two housing estates built in the 1970s that were favourably designed. In both cases, they were high-rise blocks: in Marine Parade, I lived on the 18th floor of a common corridor flat that was blessed with a partial view of the East Coast Parkway and the sea; in Queenstown I lived one floor higher, looking out at other flats. While researching this essay, I also learned that the Queenstown block at Mei Ling Street was one of the first two HDB “point blocks” ever constructed.15

Both flats were on a north-south facing, well-ventilated (even during monsoonal downpours) and nestled among densely inhabited clusters of another 15 or so similarly tall blocks. The estates had been designed to include markets, hawker centres, coffee shops and schools within their confines. Despite living so far above ground level, on quiet afternoons I could sometimes hear the faint sounds of children playing at the void deck or a bus passing by in the distance. And although I was surrounded by several thousand residents within a short walking radius, within the flat it felt quiet and private enough to be a personal refuge.

However, perhaps because of my own introverted nature, or because I was living on my own and working from home, one aspect of HDB life that I confess I neglected was getting to know my neighbours. This was in fact an initial cause of concern to urban planners and sociologists in the 1960s and 70s as Singaporeans were moved into ever higher and more densely populated flat environments. How would strangers from different cultures and backgrounds get along in such tight quarters? Would it lead to conflict or community? And could the design of buildings and neighbourhoods do anything to make living in HDB estates more pleasant?

Villages in the Sky

Given Singapore’s small land area and the swelling population, building vertically seems intuitive today, but in the 1960s, the government’s commitment to high-rise public housing went against global trends. Cities in the West had numerous cautionary tales of post-war modernist high-rise public housing gone wrong, from Pruitt-Igoe in St Louis and Cabrini-Green in Chicago in the US, to Trellick Tower in London.16

However, as sociologists like Gerda Wekerle have pointed out, “Pruitt-Igoe is no more representative than is the John Hancock Center of high-rise living”, and much research about the problems of high-rise housing is specifically about “the problems created by concentrating multi-problem families in housing stigmatised by the rest of society.”17 On the other hand, after looking at the Singapore example, sociologist Chua Beng Huat has pointed out that rather than relying on “simplistic architectural determinism”, “perhaps the problem with highrise public housing is not with the built-form but with the financing, management and, indeed, the tenants themselves.”18

The relationship between the built form and the people who live in the flats has been examined since the early years of HDB. One distinctive feature that has received particular attention is the common corridor, which was originally designed as a practical, cost-effective method of connecting flats in a building, but took on other meanings after residents moved in.

Given the small size of the flats in the 1960s, which limited opportunities to socialise, the common corridor became a communal space among neighbours. It gradually became akin to that of a “residential street” where neighbours encountered one another informally and children could play safely near their homes.19 In the 1970s, there were even stories of “a few enterprising older persons” who set up makeshift stalls in common corridors to sell sweets and nuts; these stalls in turn became focal points where residents (at the time mostly housewives and the elderly) would gather to chat and exchange news.20

A spectacular view of the upmarket The Pinnacle@Duxton HDB flats juxtaposed with older 1970s-style flats at Everton Park (photographed in 2016). Photo by Darren Soh.

A spectacular view of the upmarket The Pinnacle@Duxton HDB flats juxtaposed with older 1970s-style flats at Everton Park (photographed in 2016). Photo by Darren Soh.Planning something as apparently straightforward as the length of the common corridor, therefore, became an important factor in engendering neighbourly relations. Writing in 1973, Liu Thai Ker described how in the new Marine Parade estate, the long common corridor was broken up into shorter segments of 60 to 80 ft (18 to 40 m) that could become “a safer and thus more useful place for the kids [to play]”, and also “more intimate and popular as a social gathering place”.21

Indeed, the question of juggling numbers to create a sense of local community and identity in HDB estates was critical in planning not only individual floors, but entire blocks of flats. Liu recalled in his oral history interview:

“How [do] you compose a block? In fact, at some stage we talked about the “courtyard in the sky”. That means you group four to eight units of an apartment around a corridor… Instead of 20, 30 units sharing one corridor, you break it up into groups of four or eight. It’s amazing how by having only four or eight families sharing a corridor, the sense of community is very strong.

… If you look at the whole block, you imagine that there are maybe a dozen or two, or a few dozen small villages, so to speak, in the sky, consisting of four to eight families [each].”22

Of course, despite these architectural interventions, neighbourly relations in the early years of HDB (and even today) were not always rosy. In the first few decades, there were plenty of complaints from HDB residents relating mostly to social frictions that accompanied the sudden onset of high-density living. For example, a survey of HDB residents in 1972 found that a common complaint was about “rubbish thrown from upstairs” and noise. Even though every flat had its own rubbish chute, some residents left their rubbish along common corridors and staircases and even threw them out their windows.

There were also complaints about noise and, in particular, about children, who were accused of vandalising lifts and causing breakdowns. Moreover, families felt there were inadequate play areas for children in the housing estates. Parents tended to confine their children to playing inside their flats or along the corridor outside their flats within sight and to ensure that they did not fall in with “bad company”.

Yet despite these problems, studies also found that after the first year or two of social adjustment, HDB residents came to value the “spacious, clean and pleasant environment of the new flats,” as well as the convenience of electricity, running water and security.23 The demand for HDB flats shot up. As Liu recollected, whereas previously people had written letters to the press to complain about being forcibly resettled into HDB flats, by the 1970s such letters were grumbles instead about why it took so long for them to get their flats.

A Sign of Home

I now live in a second-floor HDB flat in Toa Payoh. It was built in the 1980s, I am told, on the site of a former kampong that presumably had to make way for the expanding HDB new town. After decades of flitting between high-rise apartments, I am now living close to the ground, where chirping birds in the trees are sometimes at eye level from my window and the neighbourhood cat from the void deck occasionally trails me up the stairs to my front door.

Moving from high-rise to low-rise has reminded me that there are many aspects of HDB living that are fostered by the design of the flat and the neighbourhood, which people have come to take for granted. As Liu wrote in 1973, “The debate is not on high-rise versus low-rise, but on identifying the shortcomings and looking for compensating amenities.”24

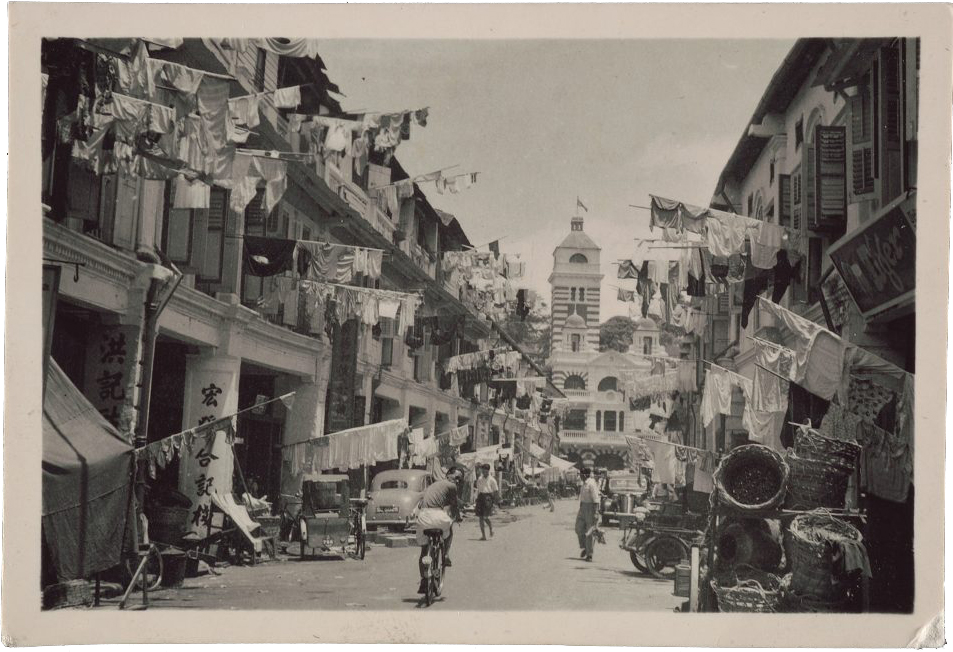

Perhaps the best image that captures how the design, actual use and symbolism of HDB flats come together is the now ubiquitous scene of laundry hanging on bamboo poles outside kitchen windows and flapping in the wind. Regardless of flat type, income level or cultural background, all HDB residents – save the few exceptions who own energy-guzzling clothing dryers – share a common practice: they dry their laundry in the sun, even though this means putting one’s most intimate attire on public view. It also has implications for neighbourliness – everyone knows that it’s not polite to let one’s wet clothing drip onto the neighbour’s laundry downstairs.

This practice of hanging clothes on bamboo poles originated with shophouse dwellers in Singapore’s city centre, long before the rise of public flats (just look at any archival photo of Chinatown or Singapore River neighbourhoods).

Before people moved to high-rise HDB flats, some lived in decrepit shophouses like these on Hock Lam Street (c.1940s). When the occupants moved to HDB flats, they brought with them the habit of hanging laundry on bamboo poles suspended outside their windows. Courtesy of the National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board.

Before people moved to high-rise HDB flats, some lived in decrepit shophouses like these on Hock Lam Street (c.1940s). When the occupants moved to HDB flats, they brought with them the habit of hanging laundry on bamboo poles suspended outside their windows. Courtesy of the National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board.Interestingly, in his oral history interview, Liu presents his view on the “unsightliness” of laundry hung from HDB windows:

“If you look at it from the sociological or psychological point of view, I think the clothing hanging at the window tells people that this estate is alive, it’s teeming with people. It’s not aesthetically pleasing only by Western standard. But by Asian standard, it’s fine, it’s Asian.

“You know, there have been many attempts [by] people [who] have been telling me to get rid of this clothes hanging. I was never interested because I felt that it is a sign of welcoming home. It gives you a warm feeling. I was never interested to get rid of it.”25

Critics may characterise – or caricature – HDB life as compartmentalised, emotionless and dystopian, and HDB flats as drab, homogenous environments with equally colourless inhabitants. Yet somewhere between the imperatives of modernist efficiency and socialist-inflected social re-organisation, several generations of Singaporeans have not only adapted to live in these admittedly utilitarian structures, but created their own meanings in the space, beyond what the original planners and designers could have envisioned.

Yu-Mei Balasingamchow is the co-author of Singapore: A Biography (2009) and works on history, art and culture projects. She writes fiction and has also curated exhibitions for the National Museum of Singapore and the National Archives of Singapore. Her website is [www.toomanythoughts.org](https://www.toomanythoughts.org).

Yu-Mei Balasingamchow is the co-author of Singapore: A Biography (2009) and works on history, art and culture projects. She writes fiction and has also curated exhibitions for the National Museum of Singapore and the National Archives of Singapore. Her website is [www.toomanythoughts.org](https://www.toomanythoughts.org).

References

Centre for Liveable Cities. (2015). Built by Singapore: From slums to a sustainable built environment (p. 17). Singapore: Centre for Liveable Cities. Retrieved from PublicationSG.

Homes for 60,000 people. (1960, December 8). The Straits Times, p. 4. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Singapore: The first ten years of independence, 1965 to 1975 (p. 198). (2007). Singapore: National Library Board and National Archives of Singapore. Call no.: RSING 959.5705 SIN-[HIS]

Yong, C. (2013, May 17). Hard for old-timers to say goodbye. The Straits Times, p. 8. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Notes

-

Wong, T. C., & Guillot, X. (2005). A roof over every head: Singapore’s housing policy between state monopoly and privatisation (p. 68). Calcutta: Sampark. Call no.: RSING 363.5095957 WON ↩

-

Gifford, R. (2007). The consequences of living in highrise buildings. Architectural Science Review, 50, 2. Retrieved from University of Victoria website. ↩

-

Fernandez, W. (2011). Our homes: 50 years of housing a nation (p. 49). Singapore: Straits Times Press. Call no.: RSING 363.585095957 FER ↩

-

Soh, E. K. (Interviewer). (1997, May 20). Oral history interview with Alan Choe Fook Cheong [Transcript of Recording No. 001891/18/7, p. 3]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

Soh, E. K. (Interviewer). (1997, May 20). Oral history interview with Alan Choe Fook Cheong [Transcript of Recording No. 001891/18/7, p. 3]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

Wong & Guillot, 2005, p. 61. ↩

-

Soh, E. K. (Interviewer). (1997, May 20). Oral history interview with Alan Choe Fook Cheong [Transcript of Recording No. 001891/18/7, p. 11]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

Loh, K. S. (2013). Squatters into citizens: The 1961 Bukit Ho Swee fire and the making of modern Singapore (p. 214). Singapore: Asian Studies Association of Australia in association with NUS Press and NIAS Press. Call no.: RSING 307.76095957 LOH ↩

-

Wong & Guillot, 2005, p. 57 ↩

-

Quah, I. (Interviewer). (1996, September 12). Oral history interview with Liu Thai Ker [Transcript of Recording No. 001732/29/13, p. 109]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

Quah, I. (Interviewer). (1996, February 26). Oral history interview with Liu Thai Ker [Transcript of Recording No. 001732/29/16, p. 143]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

Quah, I. (Interviewer). (1996, February 26). Oral history interview with Liu Thai Ker [Transcript of Recording No. 001732/29/16, p.143]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

Quah, I. (Interviewer). (1996, September 12). Oral history interview with Liu Thai Ker [Transcript of Recording No. 001732/29/13, p. 115]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

Liu, T. K. (1983). A review of public housing in Singapore (p. 9). Singapore: National Trades Union Congress. Call no.: RSING 363.585095957 LIU ↩

-

National Heritage Board. (2016). The first point blocks. Retrieved from Roots website. ↩

-

Pruitt-Igoe, Cabrini-Green and Trellick Tower were large, high-rise public housing projects for low-income residents built from the 1950s to the early 70s. They soon became notorious for social problems such as gang activity, drug use and violence, and came to symbolise the pitfalls of mass urban housing. ↩

-

Vanderbilt, T. (2015, June 2). The psychology of skyscrapers. Fast Company. Retrieved from Fastcodesign website. ↩

-

Chua, B. H. (1997). Political legitimacy and housing: Stakeholding in Singapore (p. 113). London and New York: Routledge. Call no.: RSING 363.585 CHU ↩

-

Wong, A., & Yeh, S. (Eds.). (1985). Housing a nation: 25 years of public housing in Singapore (pp. 58, 71). Singapore: Housing and Development Board. Call no.: RSING 363.5095957 HOU ↩

-

Hassan, R. (1977). Families in flats: A study of low income families in public housing (p. 112). Singapore: Singapore University Press. Call no.: RSING 301.443095957 HAS ↩

-

Liu, T. K. (1973). Reflections on problems and prospects in the second decade of Singapore’s public housing. In P. C. Chua. (Ed.), Planning in Singapore: Selected aspects & issues (p. 26). Singapore: Chopmen Enterprises. Call no.: RSING 711.2095957 CHU ↩

-

Quah, I. (Interviewer). (1996, January 22). Oral history interview with Liu Thai Ker [Transcript of Recording No. 001732/29/14, p. 121]; Quah, I. (Interviewer). (1996, February 26). Oral history interview with Liu Thai Ker [Transcript of Recording No. 001732/29/17, p. 149]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

Quah, I. (Interviewer). (1996, February 26). Oral history interview with Liu Thai Ker [Transcript of Recording No. 001732/29/17, p. 153]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore. ↩