Saving Pearl Bank Apartments

Architectural conservation or real estate investment? Justin Zhuang ponders over the fate of a 1970s style icon that has seen better times.

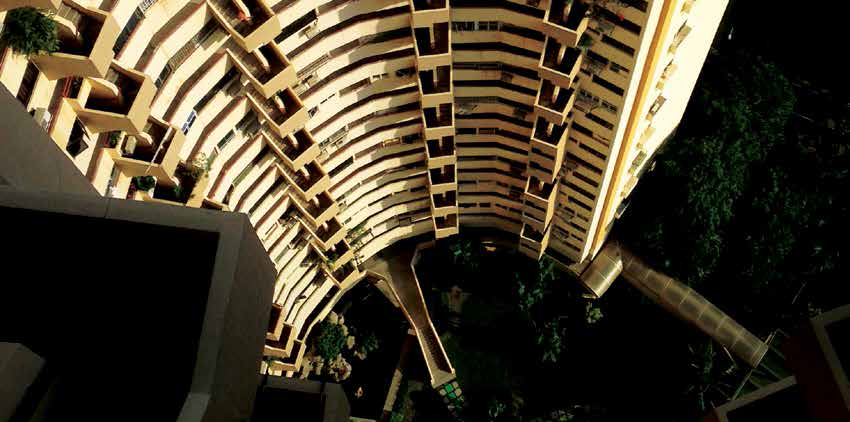

A dramatic view from a penthouse on the 38th floor of Pearl Bank apartments. This iconic block, completed in 1976, was the tallest apartment building in Singapore at the time. Photo by Justin Zhuang.

A dramatic view from a penthouse on the 38th floor of Pearl Bank apartments. This iconic block, completed in 1976, was the tallest apartment building in Singapore at the time. Photo by Justin Zhuang.A 27-storey “green tower” of residences may one day rise up at the edge of Singapore’s historic Chinatown. It will boast the Outram Park MRT station at its doorstep and Pearl’s Hill City Park as its backyard. There will even be an infinity pool and a rooftop garden. But none of these will rival the most attractive aspect of this new development if it ever comes to pass: securing the future of the Pearl Bank apartments and giving it a fresh lease of life.

This is pioneer architect Tan Cheng Siong’s unorthodox proposal to rescue what was once Singapore’s tallest block of apartments. Having witnessed the now iconic 38-storey building he designed over 40 years ago undergo three unsuccessful en-bloc attempts in the last decade, and faced with a 99-year land lease that is almost halfway expired, Tan and a group of residents have taken the unprecedented step of voluntarily applying to the Urban Redevelopment Authority (URA) for Pearl Bank to be conserved.

Not only is this the first time a multi-strata private development has made such a request – almost all the 7,200 buildings given conservation status in Singapore thus far have been proposed by the government – Tan’s conservation plan would entail demolishing part of Pearl Bank’s existing five-storey car park to build a new block of 150 apartments.

In an interview in his office at Maxwell House, Tan made clear his views on conservation: as a result of a rising population and the pressure on land resources, high-rise living has become firmly entrenched as part of the societal, environmental and architectural fabric of Singapore. If people have come to accept this fact, why don’t they learn to conserve their ageing high-rise buildings instead of tearing them down?

While Tan understands the pragmatism of maximising land values in land-scarce Singapore, his idealism is tempered by the practical business of living. While Pearl Bank is a vital piece of Singapore’s architectural history, it is also home to the people who live there, several of whom are retirees with dwindling incomes. As a result of high maintenance costs and shrinking sinking funds, the apartment building has deteriorated over the years – plagued by broken-down lifts, leaking sewage pipes, peeling paint and even rat infestations.

Given its failed en-bloc sales attempts, Tan came up with a radical idea to secure Pearl Bank’s future: seek conservation status for the property and then unlock its value by allowing a developer to construct a new block of apartments next to the original tower. The money from the sale of the new flats would then pay for the refurbishment of the ageing building as well as top up what is left of its 99-year lease.

The result would be a modern appendage to his modernist marvel – a concrete materialisation of how architecture, property and conservation intersect in Singapore. “We thought this conservation [proposal] would be a binding force because it would bring them an extension of lease, [and] … a new building,” says Tan.

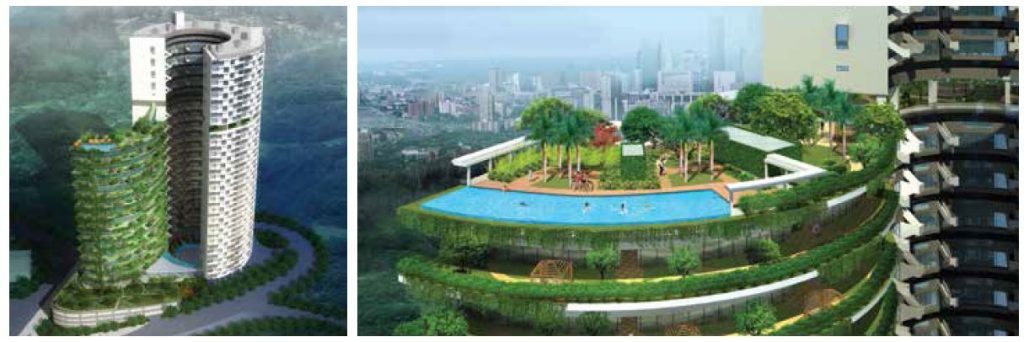

Tan Cheng Siong, the original architect of Pearl Bank, has come up with a conservation plan that entails demolishing part of the existing five-storey carpark and building a new block of 150 apartments. Courtesy of Archurban Architects Planners.

Tan Cheng Siong, the original architect of Pearl Bank, has come up with a conservation plan that entails demolishing part of the existing five-storey carpark and building a new block of 150 apartments. Courtesy of Archurban Architects Planners.Rise of an Architectural Icon

If Tan’s plan goes through, it will not be the first time he has offered a radical solution to urbanisation issues in Singapore. Pearl Bank first arose amid rapid modernisation of the city in the 1970s and 80s. Following the sales of land to private developers to build hotels, offices and commercial facilities, in 1969 the government released for the first time a piece of land in the city centre that was earmarked for private high-rise apartments. As with other land parcels offered for sale back then, the authorities had already visualised a plan for prospective tenderers: three rectilinear towers connected by a public square-cum-carpark at the foot of Pearl’s Hill.1

“Luckily, I didn’t look at it!” exclaims Tan when shown these plans during this interview – which he says he was seeing for the first time. “Otherwise, I may have followed it thinking this may be the winning design. You know how sometimes people get influenced for commercial reasons…the developer may say, ‘Eh, copy this, it’s a good thing. That’s what they want.’.”

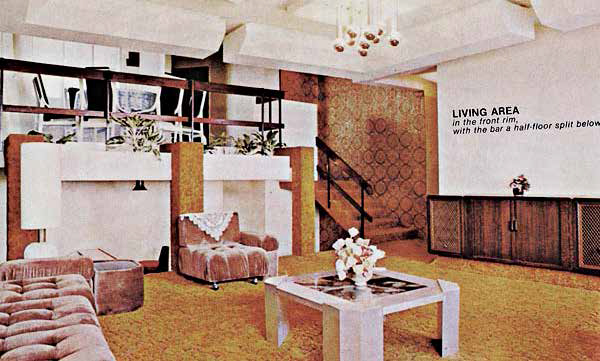

Artist’s impression of a show flat when Pearl Bank was first marketed in the early 1970s. Courtesy of pearlbankapartments.com.

Artist’s impression of a show flat when Pearl Bank was first marketed in the early 1970s. Courtesy of pearlbankapartments.com.Fortunately for the architect and his firm Archynamics Architects (which later closed and led him to start Archurban Architects Planners in 1974), the developer Hock Seng Enterprises had no such intentions when they approached his two-year-old firm to bid with them. Instead Tan found inspiration in the 85,500-sq-ft site resembling an airplane tail, drawing up a single tower that soared 561 ft above sea level – rivalling the city’s highest peak, Bukit Timah Hill – to take advantage of the panoramic views of the south of Singapore and create what would become Southeast Asia’s tallest apartment block.2

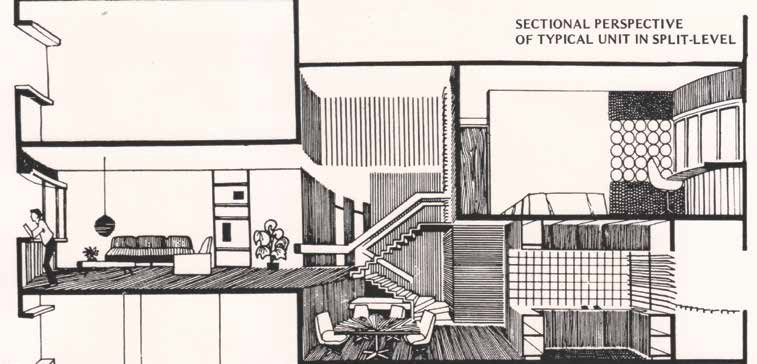

Pearl Bank’s unique horseshoe shape was grounded in Tan’s search for efficiency. Unlike a conventional point or slab block, this shape was economical in terms of materials used, offering the smallest wall-to-floor ratio.3 The opening of the building’s 270-degree sector shape – imagine the letter ‘C’– also faces west to allow for ventilation and minimise the sunset glare into its bedrooms and living rooms located on the outer rim. To fit in the maximum number of apartments yet ensure its estimated 1,500 residents could live comfortably inside, Tan devised an interlocking split design to divide the single block into 2-, 3- and 4-bedroom split-level apartments. These 288 units were generously spread eight apiece across each floor, which made it necessary for Pearl Bank to scale new heights – a groundbreaking example of high-rise, high-density living in a city where hitherto shophouses and walk-up apartments were the norm, and public housing flats just emerging.

A sectional perspective of a typical split-level apartment unit in a 1972 sales brochure. Courtesy of pearlbankapartments.com.

A sectional perspective of a typical split-level apartment unit in a 1972 sales brochure. Courtesy of pearlbankapartments.com.The building’s cost of $14 million dollars led the developer to reduce its land price in the bid, recalls Tan.4 In spite of being the lowest bidder, Hock Seng Enterprises won the tender because the government also considered the building design in its evaluation. “There was heavy calculation [by the developer] to ensure profit,” says Mr Tan. “It is only fair that people don’t invest in architecture. People invest in profit, for profit. We took a risk. He [the developer] took a risk. To be fair to him, he also saw the architectural value.”5

When Architecture Becomes Property

To realise Pearl Bank in the shortest time possible, builders Sin Hup Huat employed the relatively new slip-form construction method on a residential development for the first time in Singapore. Instead of building one level at a time with a wooden formwork and waiting over a week for the concrete to dry before proceeding – a method known as “cast in-situ” – Pearl Bank’s vertical walls were constructed by pouring concrete into a mould that was raised inch by inch as the bottom was partially set. As a result, “the vertical elements went up so fast that the horizontal elements, notably the in-situ split floors and staircases, experienced a hard time trying to catch up,” explained Building Materials & Equipment magazine in 1976.6

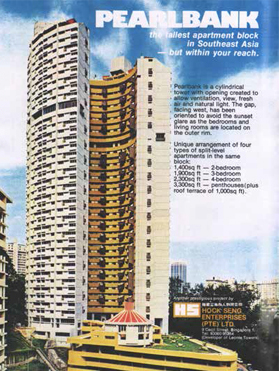

Pearl Bank was advertised as the “tallest apartment block in Southeast Asia” in the April 1976 issue of Building Materials & Equipment Southeast Asia magazine. On sale were penthouses as well as 2-, 3- and 4-bedroom apartments.

Pearl Bank was advertised as the “tallest apartment block in Southeast Asia” in the April 1976 issue of Building Materials & Equipment Southeast Asia magazine. On sale were penthouses as well as 2-, 3- and 4-bedroom apartments.Despite this, Pearl Bank was completed one-and-a-half years behind schedule. After piling started in mid-1970, progress was slowed by material and labour shortages due to a property boom in Singapore.7 “[S]ince June 1970, every 10 days has brought an announcement of a new property development project,” reported the New Nation in April 1971.8 Shenton Way came into the scene with the 50-storey DBS Building leading the way, mega mixed-used buildings like Woh Hup Centre (now Golden Mile Complex) introduced the idea of work, live and play in a single development (today the template for property development) and Singaporeans upgraded to the high life as condominiums like the luxury Beverly Mai, the cutting-edge Futura as well as Pearl Bank redefined apartment towers as the new type of middle- and upper-class housing.9

This wave of modern developments in the early 1970s overstretched the construction sector so much that the government postponed land sales for almost five years.10 Pearl Bank’s completion in 1976 was not the end of its troubles. Two years later, the developer Hock Seng Enterprises was put into receivership by its creditor, the Moscow Narodny Bank (MNB), burdened with still unsold units in Singapore’s depressed residential property market.11 Some 60 unsold apartments in Pearl Bank, including eight penthouse units, were eventually bought up by the government in 1979 as part of its move to stimulate the property market.12

Some three decades later, the property market returned to threaten Pearl Bank in a different way. By then, condominiums had become one of the 5 Cs – along with cash, car, credit card and country club membership – of life in Singapore. This culture of materialism combined with a bullish property market convinced over 80 percent of Pearl Bank’s residents to put up their homes for sale when an “en-bloc fever” swept across the city in 2007. Anderson 18 ($478 million), Gillman Heights ($548 million), Grangeford Apartments ($624 million) and Leedon Heights ($835 million), were all successfully sold, with the record going to Farrer Court, its $1.339 billion the largest ever collective sale recorded in Singapore.13 Pearl Bank somehow escaped the sales frenzy not just once but again in 2008 and 2011 – its last asking price of $750 million deemed too high by the market.14

The successive threats of en-bloc, however, galvanised a minority group of residents to save Pearl Bank. One of them is American architect Ed Poole who moved into a penthouse unit in 2000. His love for the architecture (“Pearl Bank is irreplaceable”) and the over $600,000 he has spent renovating his apartment (“And it’s still not done!”), drove Poole to hire a lawyer and rally his neighbours against the en-bloc attempts led by the “condo raiders”.15

To transform the image of Pearl Bank, which had become known as a dorm for foreign workers and a haven for vice activity, Poole started the website pearlbankapartments.com and even opened up his home to the media.16 It was after Tan was interviewed at Poole’s apartment for the TV programme, Listen To Our Walls, in 2008 that the seed of the voluntary conservation proposal was laid. “We all talked of some crazy ideas as alternatives to en-bloc. Mr Tan then did this sketch, showing a new tower. We all just laughed it off as impossible,” said Poole in a recent e-mail interview.

Architect Tan Cheng Siong sketched this new tower in 1980 when he was thinking of ways to save Pearl Bank. Courtesy of pearlbankapartments.com.

Architect Tan Cheng Siong sketched this new tower in 1980 when he was thinking of ways to save Pearl Bank. Courtesy of pearlbankapartments.com.Conservation and Conversations

The sketch created over drinks became reality in 2012 when another penthouse resident and then chairman of Pearl Bank’s management committee, Dr Lee Seng Teik, reached out to Tan to help upgrade the building and extend its lease. Only a year before, another ageing 99-year lease condominium, The Arcadia, had asked for a lease extension but was rejected because it did not meet the conditions of “land use intensification or urban rejuvenation”.17 This was why the architect proposed to increase the gross floor area of Pearl Bank with a new tower. “They called me up and I said, ‘If you really want to upgrade, you must be brave and do something to increase its value more,΄” says Tan.

Erecting a new tower on the land parcel Pearl Bank occupies seems to fly in the face of conservation as a means of preserving a city’s heritage. But as Singapore’s national body in charge of conservation, the URA, explains on its website, “Conservation is much more than just preserving a facade or the external shell of a building. It is also important that we retain the inherent spirit and original ambience of these historic buildings as far as possible.”18

This is the principle Tan uses to defend his proposal which he assures conserves the entire existing apartment block. “It does seem to change the look, but architecturally it’s not changed,” he explains. “You can’t talk about preservation in architecture. It’s conservation. And conservation means also you can adapt, reuse… but the whole meaning, the whole spirit behind still remains.”

Residents like Poole agree that it’s futile to conserve the building to its original form. Instead, the conservation proposal is an opportunity to raise much needed funds to fix some inherent architectural problems. On Poole’s wish list: turning the existing eight-lift system into plumbing shafts to address the problematic sewage pipes and replacing it with a new high-speed core of lifts.

Unlike other conserved buildings in Singapore, Pearl Bank is a block of private apartments. A resident once summed up her woes: “No doubt the building is unique and historical, but living and dealing with the inconvenience is a chore.”19 One may argue that this is no different from residents who live in pre-Independence era conserved shophouses, except in this case, all owners of the 288 units in Pearl Bank have to come to a consensus on any decision regarding the fate of the building.

This is the case with Tan’s plan too. While the merits of conservation will be assessed separately by URA, building a new block of apartments has to be agreed upon by all existing owners of Pearl Bank because it impacts upon their future ownership as governed by the Building Maintenance and Strata Management Act. Since the proposal was tabled in 2015, over 90 percent of residents have agreed to the new building. But it will be a “monumental task” to get everyone on board because some residents are too ill to make a decision and there are differences in opinion between the co-owners of some units, said Dr Lee.20

What irks the pro-conservation camp is that the same act requires only 80 percent of residents to agree to collectively sell a development that is 10 years old or more – an issue they have appealed to the Ministry of National Development to address. At the time of press, the ministry has granted the residents more time to get the 100 percent consent required or to explore other proposals.

The difference is perhaps an unintended legal expression of the gaps between architecture and home, public and private property, and even between conservation and redevelopment in Singapore. How can we lead modern lives in a building designed for earlier times? Are private residents expected to upkeep a public monument of a nation’s history? How should we balance the often diametrically opposite values that concern heritage conservation and property investment?

(Left) A rendering of what Pearl Bank would look like if the current conservation plan goes through. It involves demolishing part of the existing five-storey carpark and building a new block of 150 apartments. Courtesy of Archurban Architects Planners.

(Left) A rendering of what Pearl Bank would look like if the current conservation plan goes through. It involves demolishing part of the existing five-storey carpark and building a new block of 150 apartments. Courtesy of Archurban Architects Planners.The voluntary conservation plan for Pearl Bank provides a platform to facilitate discussions between residents, the state, the architecture community and the public. Surrounding the issue of conservation is the larger issue of what consensus looks like in Singapore today. Is it 80, 90 or 100 percent? Can it even be measured? It is a question that becomes all the more pertinent as Singapore becomes more crowded and diverse. Pearl Bank and the problems of high-rise living that ageing buildings bring with them is but a microcosm of what the city will face in the future.

“When you build super-high, it is super difficult: more people, more quarrels, more differences,” says Tan. “Because of that we have to learn how to live together in a very positive and creative way.”

Justin Zhuang is a writer and researcher with an interest in design, cities, culture, history and media. The co-founder of writing studio In Plain Words contributes to various architecture and design magazines, including Design Observer and American Institute of Graphic Art’s Eye on Design. He is the author of Independence: The History of Graphic Design in Singapore Since the 1960s (2012), Mosaic Memories: Remembering the Playgrounds Singapore Grew Up In (2014) and the catalogue for the exhibition Fifty Years of Singapore Design (2016). For more information, see http://justinzhuang.com.

Justin Zhuang is a writer and researcher with an interest in design, cities, culture, history and media. The co-founder of writing studio In Plain Words contributes to various architecture and design magazines, including Design Observer and American Institute of Graphic Art’s Eye on Design. He is the author of Independence: The History of Graphic Design in Singapore Since the 1960s (2012), Mosaic Memories: Remembering the Playgrounds Singapore Grew Up In (2014) and the catalogue for the exhibition Fifty Years of Singapore Design (2016). For more information, see http://justinzhuang.com.Notes

-

Third sale of urban renewal sites for private development. (1970, January/February). Journal of the Singapore Institute of Architects, 38, pp. 2–23. Call no.: R 720.5 SIAJ ↩

-

Wu, D. (2008, March). Pearl gem. Wallpaper, pp. 158–160. Call no.: RART 747W; Going up in S’pore S-E Asia’s tallest flats. (1970, July 13). The Straits Times, p. 24. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Wu, Mar 2008, pp. 158–160. ↩

-

Cylindrical tower provides high density accommodation in split-level apartments. (1976, April). Building Materials & Equipment Southeast Asia, pp. 34–57. Call no.: R 690.05 BME ↩

-

Quek, G., Neo, K. J., & Lim, T. (2015). Conservation conversations: Pearl Bank apartments (p. 20). Singapore: Singapore University of Technology and Design. Available in PublicationSG. ↩

-

Building Materials & Equipment Southeast Asia, Apr 1976, pp. 34–57. ↩

-

Apartment block ready at last. (1975, 10 October). New Nation, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Tan, A. (1971, April 17). Building at a faster tempo for graceful living. New Nation, p. 13. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Tan, C. S. (1972, February 1). Neck-to-neck race skywards… New Nation, p. 8. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

URA offers sites for sale to developers. (1974, April 2). The Straits Times, p. 9. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Goh, E. K., & Ong, L. K. (1976, November 5). Property companies facing an uncertain future. The Business Times, p. 4. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Teo, L. H. (1978, December 13). HUDC to buy 60 Pearlbank flats. New Nation, p. 1; Developers hail HUDC move. (1977, December 7). The Straits Times, p. 25. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Fatti, M. (2016, March 29). En bloc sales – how does it work? Retrieved from 99.co. website. ↩

-

Wang, R. (2015, August 15). URA sees merit in conservation plan for Pearl Bank. The Straits Times, p. 24; Lim, C. (2011, March 15). 3rd collective sale bid by Pearl Bank. The Straits Times, p. 19. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Lee, P. (2014, May 2). Pearl Bank still special after all these years. The Straits Times, p. 8. Retrieved from NewspaperSG; Poole, E. (2010, March 15). Interview with Ed Poole. Retrieved from Facebook. ↩

-

Pearl Bank Apartments. Retrieved from Pearl Bank Apartments website. ↩

-

Chua, S. (2011, April 12). Fighting for Arcadia. Retrived from iProperty.com website. ↩

-

Urban Redevelopment Authority. (2016, July 12). Conservation principles. Retrieved from Urban Redevelopment Authority website. ↩

-

Tay, S. C. (2007, August 5). Goodbye Famous 5?The Straits Times, p. 40. Retrieved from NewspaperSG ↩

-

Chow, C. (2016, March 3). Bold bid for conservation. Retrieved from The Edge Property website. ↩