Soft Hands But Steely Hearts: Women and Their Art

A coterie of women sculptors in Singapore has successfully redefined this once male-dominated art form. Nadia Arianna Bte Ramli tells you more.

Han Sai Por’s “20 Tonnes – Physical Consequences” (2002) currently stands in front of the National Museum of Singapore. It is made up of six granite blocks and cost about $20,000 to create. Courtesy of the National Museum of Singapore.

Han Sai Por’s “20 Tonnes – Physical Consequences” (2002) currently stands in front of the National Museum of Singapore. It is made up of six granite blocks and cost about $20,000 to create. Courtesy of the National Museum of Singapore.“If I showed up in a feminine dress like this, people don’t believe I’m a sculptor!”1

– Elsie Yu

Whether the medium is granite, bronze, steel or clay, the art of shaping, moulding and chiselling the material into a sculptural work of art demands more than brute strength. Yet, some hold the view that the art form requires certain masculine qualities in order to bend, carve or shape even the most malleable of materials into what may be deemed a “feminine” sculpture. What does gender have to do with art? The question was raised by Susie Lingham in the Text & Subtext forum in 2000:

“In sports events, men and women’s events are separated on the argument that men have more physical strength. But in art, is there a necessity to set up another ring for women artists to wrestle for relevance in the art world? Is this not a way of marginalising women?”2

Women sculptors around the world,including those in Singapore, have wrestled countless obstacles in order to pursue their artistic passions. From sourcing of materials and seeking funds and opportunities to exhibit their works, to struggling with competing priorities and the challenges of being an artist in a monetised capitalist society, these are all admittedly not gender-specific issues. They are issues that all artists face – regardless of gender.

In spite of these obstacles, women sculptors in Singapore, from Kim Lim to Kumari Nahappan, have carved out certain success from whatever materials they could lay their hands on. The fruits of their labour stand in public, private and commercial spaces – a testament to the grit and gumption as well as the creative talents of a small but influential group of women sculptors in Singapore.

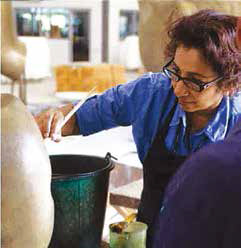

Kumari Nahappan working on the patina for a sculpture in Ayutthaya, Thailand, 2006. All rights reserved, Sabapathy, T. K. (2013). Fluxion: Art & Thoughts: Kurmari Nahappan. Singapore: Editions Didier Millet.

Kumari Nahappan working on the patina for a sculpture in Ayutthaya, Thailand, 2006. All rights reserved, Sabapathy, T. K. (2013). Fluxion: Art & Thoughts: Kurmari Nahappan. Singapore: Editions Didier Millet.From Decoration to Art

Records show that a pioneer exhibition of women’s work was held in October 1931 at the Young Women’s Christian Association in Singapore. Works of artistic merit were grouped together along with “useful” crafts. A newspaper notice for the exhibition states that it included “all kinds of sewing, embroidery, art work, photography, cooking… by the young married women who are just beginning to realise the delights of making artistic and useful things”.3 In those early days, art by women seemed to be largely decorative in nature and merely a leisurely pursuit by women with time on their hands.

In the 1930s, a European sculptor by the name of Dora Gordine lived and worked in Singapore and Johor. During her time here, she was commissioned to create three sculptures for the Municipal Building (later renamed as the City Hall until its recent reincarnation as the National Gallery Singapore [NGS] together with the Supreme Court building next door).

Dora Gordine working on the head of a child in her studio at Dorich House, London, c.1950s. National Monuments Record, English Heritage, Swindon. All rights reserved, Black, J., & Martin, B. (2007). Dora Gordine: Sculptor, Artist, Designer. London: Dorich House Museum, Kingston University in association with Philip Wilson Publishers.

Dora Gordine working on the head of a child in her studio at Dorich House, London, c.1950s. National Monuments Record, English Heritage, Swindon. All rights reserved, Black, J., & Martin, B. (2007). Dora Gordine: Sculptor, Artist, Designer. London: Dorich House Museum, Kingston University in association with Philip Wilson Publishers.The sculptures were of three heads depicting an Indian, a Chinese and a Malay.4 These bronze busts were crafted in the classical tradition of “universal and idealised human forms” in three-dimensional style.5 The purchase of these art works for the Municipal Building was described as a watershed event: “the first time in the history of this Colony that the acquisition of a subject of pure art has been realised”.6

Coming at a time when most of the sculptures in the colony took the form of busts or statues, and were largely commemorative or decorative in nature, Gordine’s works of “pure art” were indeed welcome acquisitions. Today, these sculptures can be found in the Singapore Gallery of the NGS.

Bronze sculptures of a Malay head (left) and Chinese head (right) by Dora Gordine were commissioned for the Singapore Municipal Building in the early 20th century. All rights reserved, Black, J., & Martin, B. (2007). Dora Gordine: Sculptor, Artist, Designer. London: Dorich House Museum, Kingston University in association with Philip Wilson Publishers.

Bronze sculptures of a Malay head (left) and Chinese head (right) by Dora Gordine were commissioned for the Singapore Municipal Building in the early 20th century. All rights reserved, Black, J., & Martin, B. (2007). Dora Gordine: Sculptor, Artist, Designer. London: Dorich House Museum, Kingston University in association with Philip Wilson Publishers.Beyond the Western community of artists, annual art exhibitions such as those held by the Singapore Art Society drew local artists to the fore. On 22 September 1955, the society held the first art show by Malayan women artists: altogether 60 compositions from 42 women from Malaya and Singapore were selected from 120 artistic submissions. Mrs Dorothy Bordass, chairman of the organising committee, was hopeful that the endeavor would encourage artistic expressions of local subject matter by local talents:

“The number of entries and the excellent, creative quality of individual canvases indicate that Malaya’s women artists are finding encouragement in self-expression in local subject matter. Art can offer Malaya’s women rewarding careers. Very little has been done so far to encourage artistic expression…It is our hope that women artists thus will be encouraged to advance their talents.”7

Art teachers and students were encouraged to showcase their talents by taking part in exhibitions. One such teacher was Mrs A. Gunaratnam. A former teacher at Raffles Girls’ School, one of her plaster sculptures fetched the highest price for an artwork at a 1950 Singapore Art Society exhibition.8 Priced at $500, this was a very respectable sum of money in those days for an artwork by a relatively unknown person.

Mrs Gunaratnam was one of the very few women sculptors in Singapore then, having begun exhibiting her works since 1948. Her talent did not go unnoticed – she sat on the selection committee for a 1951 art exhibition, alongside local pioneer artist Liu Kang and the last British Director of the Raffles Museum in Singapore, Dr Carl Alexander Gibson-Hill.9 One of her sculptured portrait busts, “Mavis – A Study” (1950), was described by the art historian T. K. Sabapathy as remarkable for the time, with her attention to both anatomical details and characterisation.10 Mrs Gunaratnam’s reputation grew, and her statues and sculptures were even bought by private collectors in India and England.

While women artists were progressively moving beyond the home and expanding their artistic horizons, some were still caught in a bind between domestic responsibilities and their artistic inclinations.

At a women-only art exhibition in 1975, held in celebration of International Women’s Year, some artists believed that women had finally achieved complete independence while others felt that, unlike their male counterparts, some women had to sacrifice their artistic ambitions and turn their attention to the home and the needs of the family first.11 This tension between social responsibilities and individual expression is a continued source of conversation for women working on sculpture and heavy art installation works even until today.12

A Collective Consciousness

In 2001, a cross-cultural collaboration exhibition, “Women Beyond Borders”, with its aim to establish a community of women’s voices and visions, ended its world tour with its Singapore exhibition.Initiated by a group of American women artists, “Women Beyond Borders: Singapore” was primarily a women’s project. It saw established women artists as well as female members of the public creating sculptures, specifically, transforming a pinewood box, measuring a mere 2.5 by 3 by 2.5 inches, into a work of art.13 The exhibition’s focus was “not on account that they are women that alone made such work invaluable, but because largely owing to the theme, they reveal nuggets of thoughts and insights on themselves as women”.14

At the Singapore edition of the exhibition, now leading artists such as Kumari Nahappan, Yvonne Lim and Suzann Victor were but a few of the women who created small but powerful sculptures from the boxes they were handed out. This global inquiry of what it meant to be a woman through art drew attention to the larger liberties afforded to women across national boundaries, providing a united yet diverse voice for the effort.

A decade earlier, art by women and about women was also the focus of the landmark 1991 National Museum Art Gallery exhibition, “Women and Their Art”, curated by Susie Koay. It was a defining moment for the women’s art scene in Singapore, given that the last all-female exhibition was held more than 30 years ago. Diana Chua’s sculpture of a female torso, “In Between No.11”, wrapped in mirror shards beneath a veneer of gauze, veered away from the conventional sensuality of smooth torsos and curved, inviting forms. This juxtaposition between hard and soft, and male and female, was just one of the many artworks that redefined “the stereotyped image of the female artist as one who paints pretty things” to “a serious artist of serious issues”.15

A growing community of women artists, though not necessarily feminist artists – there is a difference – was further shaped by art forums such as Huangfu Binghui’s Text & Subtext and artist collectives such as Women In The Arts (WITAS)16 and 5th Passage Artists Ltd. While these initiatives were not art-form specific, women sculptors also benefitted from the focus on the representation and network of women artists they could tap into. With diverse dialogues and initiatives, women’s art and issues took shape within the community.

Shaping Interests

Sculpture as an art form in Singapore has generally been a less-travelled terrain in comparison with other art forms such as painting and pottery. Sabapathy described the entry of sculpture into the local art world as “rather timid and inconspicuous”, first appearing sporadically in the 1950s in expositions that were otherwise dedicated to paintings.17

At the opening of the first exhibition dedicated to sculptural works in 1967, then Deputy Prime Minister Toh Chin Chye called on artists to “organise a little movement to kindle the country’s interest in sculptured art” that “could give life and beauty to the vast bareness of the city”.18 Fast forward 15 years later to 1982, Sabapathy noted the continued interest in painting over sculpture:

“It has been 15 years since the first national exposition. This neglect is a symptom of the condition of sculpture here. There is little doubt that it is secondary to painting, which dominates the art world here. The demands of the art market have only served to entrance the primacy of painting. The portable picture is mobile and seemingly self-effacing in that it is absorbed into the wall. This enhances it as a commercial product and commodity.”19

Women sculptors were thus venturing into what was a relatively small space in the arts scene. The hefty cost of creating sculptural exhibitions may be (and still is) a strain for some. 1995 Cultural Medallion recipient Han Sai Por’s “20 Tonnes – Physical Consequences” (2002) cost about $20,000 to create, while construction costs alone for Elsie Yu’s “Towards Excellence” (1987) was a whopping $80,000.20

Han Sai Por at work on one of her sculptures. She was awarded the Cultural Medallion in 1995. All rights reserved, Han, S. P. (2013). Moving Forest. Singapore: Singapore Tyler Print Institute.

Han Sai Por at work on one of her sculptures. She was awarded the Cultural Medallion in 1995. All rights reserved, Han, S. P. (2013). Moving Forest. Singapore: Singapore Tyler Print Institute.While government initiatives such as the Public Sculpture Masterplan 2000 (and the more recent Public Art Trust) have sought to ease these costs and allow artists to concentrate on their work, private organisations are also important stakeholders in promoting the appreciation of sculpture as an art form. City Developments Limited and its biennial Singapore Sculpture Award is one such example of a private corporation shaping the visibility and appreciation of sculpture in Singapore.21

CapitaLand, one of the largest real estate companies in Singapore, has commissioned public art for display at its commercial and residential premises. Its first work of art was Han’s large-scale sculptural installation, “Shimmering Pearls” (2000) at Capital Tower in the heart of the financial district.22 With corporate commissions, sculptors are able to work more freely on a more ambitious scale. However, because such commissioned works tend to be awarded to well-known sculptors, new and emerging talents run the risk of being ignored, irrespective of gender.

Creating dedicated spaces to showcase three-dimensional art was the next step in engendering public interest and encouraging the art form. Sculpture Square, which opened in 1999, served this very purpose. Its inaugural exhibition, “Provocative Things”, highlighted conventional sculptural works and more abstract sculptural installations. Chng Seok Tin’s “Kuantan Boat Song” (1999), with coconut husks cast in bronze, and Kumari Nahappan’s “precisely…..360” (1999), an installation of found objects, made of both natural and man-made material, fell into the latter category.

Chng Seok Tin with sculptures from her “Life Like Chess” exhibition in 2001. Photo was taken in Marina Bay against the Central Business District. Courtesy of Chng Seok Tin.

Chng Seok Tin with sculptures from her “Life Like Chess” exhibition in 2001. Photo was taken in Marina Bay against the Central Business District. Courtesy of Chng Seok Tin.In 2001, the formation of the Sculpture Society, led by Han, further advanced the development and appreciation of sculpture through a tight-knit community of passionate sculptors.23

Labours of Love

It cannot be denied that for sculptures that emphasise a certain size, some physical strength is called for when working with the material. In a society given to using gender-related terms, such works have been described as “masculine”. Elsie Yu’s “Joyous Rivers” (1987), with curves of architectural steel that mimic the flow of life-giving river, has a massive base area of 27.9 sq m and reaches 10 m at its highest point. When it was first unveiled at the opening ceremony of Clean Rivers Commemoration ’87, the press viewed her work as “most masculine”.24 Even so, Yu’s metal sculptures, such as her 1992 work “Soaring Vision”, also embody a certain sense of the feminine, with their fluid lines and refinement.

“Soaring Vision”, a 13-metre high bronze and stainless steel sculpture by Elsie Yu once stood at the Marina City Park. This is Yu’s interpretation of Singapore’s aspirations. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

“Soaring Vision”, a 13-metre high bronze and stainless steel sculpture by Elsie Yu once stood at the Marina City Park. This is Yu’s interpretation of Singapore’s aspirations. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.The exploration of the feminine and masculine binary cuts through a number of sculptures, pushing the boundaries of what an artwork by a female artist would look like. Early ceramic sculptures by Jessie Lim, described as having a mix of the “natural and metaphysical”, seem to question this binary:

“Some people tell me, ‘your work was neither feminine nor masculine – you don’t know who made it.’ I like that. I like that they can stand on their own.”25

Jessie Lim’s ceramic sculpture, “Infinity” (2012), is a departure from her spiral sculptural ceramics. Courtesy of National Gallery Singapore.

Jessie Lim’s ceramic sculpture, “Infinity” (2012), is a departure from her spiral sculptural ceramics. Courtesy of National Gallery Singapore.Hard and heavy materials, such as granite and marble, are challenging for both male and female sculptors to manipulate into their desired shape and form. However, granite is a favourite medium of Han Sai Por’s and constitutes a considerable part of her oeuvre. Her works are often inspired by nature, but “… not a slavish representation of visual form”, rather being able “to make the subtle and small large and true to the stature of life’s enormous possibilities”.26

Han’s marble work, “Growth” (1985), shows sensitivity in controlling and manipulating the material, “effect[ing] these stone surfaces with subtle, tactile nuances”.27 Her working relationship with materials has been described as loving and sympathetic, as she seeks to understand the characteristics of the materials. Instead of controlling and “fighting” hard materials like stone – as male sculptors are wont to do – she works with the natural curves and edges of the stone, allowing the natural formations to inspire the shape and order of each art piece.28 Han’s recent works have included paper-pulp media and printmaking, while still exploring and examining nature, such as products of the forest, including seeds and pods.

Kim Lim, an early Singaporean female sculptor, has attempted to distil the essence of nature and time into her stone sculptures. Shunning labels, she once shared in a 1981 interview that given her Asian heritage and background, her inspirations are vastly different from the traditions of the minimalists:

“I am far more motivated by the organic and by nature. Although my work is entirely abstract and perhaps visually does not necessarily relate to natural phenomena, my inspiration is often derived from natural rhythms, such as the human pulse, or by visually rhythmic things, such as vertebrae.”29

Her stone sculptures, “Flow” (1982) and “Gobi” (1982), which were shown in a 1984 exhibition at the National Museum Art Gallery, Singapore, were described as a “joint venture: the balanced results of the willed and unwilled forces upon raw materials”.30 Her quiet approach was ahead of its time, given that the Singapore art scene during this period was more about figuration or the representational, and other “colourful noises” of the time.31 With this, Kim Lim etched her name as one of the pioneer contemporary women artists in Singapore.

For 2005 Cultural Medallion recipient Chng Seok Tin, sculpture was “regarded as something of a rebirth” as she expanded her artistic repertoire to the tactile art form following her untimely loss of sight in 1988.32 Chng began as a printmaker but has had a hand in installation work as well. Constantly exploring different ways of “making art”, Chng writes:

“Well then, what is art? What is good art? Are the works in world class art museums considered first class objet d’art? After travelling and seeing so much, I have become unsure myself! All I know is that I am devoted to art making, and I do not really care if my works adhere to the aesthetic standards of most people…If you intentionally pursue perfection in art, then art would become dull and useless!”33

Natural Themes

Some of the early artworks by Romanian-born Singaporean sculptor Delia Prvacki, who works with materials such as bronze, glass fibre reinforced concrete, and ceramics, included motifs of nature. With a body of work spanning over 40 years, Prvacki’s works include quiet, intimate pieces as well as bold and dramatic public installations.

Romanian-born Singaporean sculptor Delia Prvacki posing in front of her sculpture titled “7 Days” (2006), a composite of seven pieces made of glass reinforced concrete (GRC) with metallic sub-frames and handmade mosaics. Courtesy of Delia Prvacki.

Romanian-born Singaporean sculptor Delia Prvacki posing in front of her sculpture titled “7 Days” (2006), a composite of seven pieces made of glass reinforced concrete (GRC) with metallic sub-frames and handmade mosaics. Courtesy of Delia Prvacki.For Prvacki, art is more than just an expression of the natural environment. Her public sculpture project, “Plein Air” (2006), was interactive and integrative with its surroundings. The sculptures were meant to look like they were “deposited by the ebb and flow of the ocean” and “had to appear natural in the landscape, like they were born there”.34 Her earlier stonework, “Grass Movement” (1993), articulated the more untamed nature of beauty with the horn-shaped pieces growing wildly out of the ground.35

Her more recent installation “Mine and Rare Earths” (2010) dealt with the environment differently, exploring the relationship between raw materials and ores drawn from the earth and their impact on new technologies and the global economy. 36 “Under the broad themes of nature, the environment of the city and nation-building”, the massive mural, “Singapore Tapestry” (2015), was a community-based artwork guided by Prvacki. Commissioned by the Land Transport Authority for Marina South Pier MRT Station, Prvacki pulled together the “divergent inspirations” of nearly 2,000 participants in this ambitious work of public art.37

Representations and abstractions of nature figure strongly in Kumari Nahappan’s sculptures too. While she engages in painting, mixed media and installation art, it is Nahappan’s larger than life bronze sculptures of vibrant red capsicums “Pedas-Pedas”38 (2006) behind the National Museum of Singapore, the supersized saga seed “Saga” (2007) at Singapore Changi Airport Terminal 3 and “Nutmeg & Mace” (2009) at ION Orchard that the public are most familiar with.

“Nutmeg & Mace” (2009) by Kumari Nahappan is a two-tonne bronze sculpture installed at the outdoor space of Ion Orchard shopping mall in the heart of Orchard Road. All rights reserved, Sabapathy, T. K. (2013). Fluxion: Art & Thoughts: Kurmari Nahappan. Singapore: Editions Didier Millet.

“Nutmeg & Mace” (2009) by Kumari Nahappan is a two-tonne bronze sculpture installed at the outdoor space of Ion Orchard shopping mall in the heart of Orchard Road. All rights reserved, Sabapathy, T. K. (2013). Fluxion: Art & Thoughts: Kurmari Nahappan. Singapore: Editions Didier Millet.Saga seeds feature prominently in Nahappan’s works. Sculptural works such as “Multiples” (2000) and “Saga” (2007), which draw on the “potency” of saga seeds, “loop back to the artist’s childhood… [and] … to the garden – a primary resource and locus for inaugurating her art”.39 The intense red colour of these seeds is characteristic of her oeuvre. Her early sculptures, such as “Maia Two” (2005), have deep red hues and are named after stars, which Sabapathy describes as “embody[ing] kernels of energy”. 40

Sculpture Today

While Sculpture Square has since ceased operations as a dedicated space for sculptures, the art form has found its place firmly alongside other forms of visual arts in private and public art galleries in Singapore.

Commissions of public art also continue to ensure the visibility of sculptural art in the Singapore landscape. As part of Singapore’s Golden Jubilee celebrations in 2015, three new public sculptures were commissioned to mark the occasion. Departing from her signature stonework, Han Sai Por, the sole female sculptor who won a commission, created a monochromatic sculptural installation called “Harvest” (2015), which took pride of place at the Esplanade concourse from August 2015 to January 2016.41

Sculptures, particularly public sculptures, are meaningful only when they are considered in the context of their surroundings. In much the same way, despite the seemingly static nature of their works, women sculptors in Singapore have always been adapting to their environments, carving a space for themselves and proving that it takes more than sheer physical strength to turn a hunk of granite into a sublime sculptural art form.

Nadia Arianna Bte Ramli is an Associate Librarian with the National Library, Singapore. She works with the arts collections, focusing on literary and visual arts.

Nadia Arianna Bte Ramli is an Associate Librarian with the National Library, Singapore. She works with the arts collections, focusing on literary and visual arts.Notes

-

De Souza, J. (1987, October 28). Elsie Yu: Lady of steel. The Straits Times, p. 25. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Nayar, P. (2000, June 24). ART the Asian woman. The Business Times, p. 19. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Exhibition of women’s work. (1931, September 26). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser (1884–1942), p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Singapore Art Museum. (1998). Imaging selves: Singapore Art Museum collection exhibition series 1998–1999 (p. 23). Singapore: Singapore Art Museum. Call no.: RSING 759.95 IMA ↩

-

Kwok, K. C. (1996). Channels and confluence: A history of Singapore art (p. 31). Singapore: Singapore Art Museum. Call no.: RSING 709.5957 KWO ↩

-

Dora Gordine’s sculpture. (1931, January 30). The Straits Times, p. 12. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

42 Malayan women enter art show. (1955, August 11). The Singapore Free Press, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

S’pore teachers’ art show. (1950, October 23). The Singapore Free Press, p. 3. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Colony art show in Oct. (1951, September 25). The Straits Times, p. 8. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Sabapathy, T. K. (1990, April 12). New approach but no gems. The Straits Times, p. 5. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Chew, M.-L. (1975, June 24). Woman artists show their colours. The Straits Times, p.10. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Sian, E. J. (1999, April 24). Is there such a thing as women’s art? The Straits Times, p. 9; De Souza, J. (1987, October 28). Elsie Yu: Lady of steel. The Straits Times, p. 25. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Fan, J. (2001). Something out of nothing? In Women beyond borders: Singapore: Sculpture, 7 March–13 May, 2001 (p. 3). Singapore: Sculpture Square. Call no.: RSING 730.95957 WOM ↩

-

Wong, S. (2001). Rib-in man: An imaginative journey of a box. In Women beyond borders: Singapore: Sculpture, 7 March–13 May, 2001 (p. 5). Singapore: Sculpture Square. Call no.: RSING 730.95957 WOM ↩

-

Wong, S. (1991, August 15). Of women by women. The Straits Times, p. 6. Retrieved from NewspaperSG ↩

-

Heng, A. (2011). Singapore contemporary artists series: Amanda Heng: Speak To Me, Walk With Me. Singapore: Singapore Art Museum. Call no.: RSING 709.2 HEN ↩

-

Sabapathy, T. K. (1991). Sculpture in Singapore (p. 22). Singapore: National Museum. Call no.: RSING 730.95957 SAB ↩

-

Dr Toh’s call to kindle interest in sculpture (1967, April 22). The Straits Times, p. 4. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Sabapathy, T. K. (1991, November 15). Carving a niche. The Straits Times, p. 3. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Sim, A. (2002, March 15). Living stones. The Straits Times, p. 4. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Jacob, J. (2007, January 26). CityDev unveils its first public artwork. The Business Times, p. 10. Retrieved from NewspaperSG ↩

-

Wong, H. W. F. (2015). CapitaLand: The art of building communities. Singapore: CapitaLand Limited. Call no.: RSING 709.5957 WON ↩

-

Sculpture Society (Singapore). (2016). Welcome to Sculpture Society (Singapore). Retrieved from Sculpture Society (Singapore) website. ↩

-

Tan, J. (1987, August 30). Elsie’s joy in steel a sure eye-grabber. The Straits Times, p. 11. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Tan, B. T. (2011). Women artists in Singapore (pp. 98–99). Singapore: Select Publishing. Call no.: RSING 704.042095957 TAN ↩

-

Barnes, R. (1981, November 24). Of an artist and the tempo of life. The Straits Times, p. 5. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

National Museum Art Gallery (Singapore). (1976). National Museum Art Gallery: Singapore & Malaysia art exhibitions. Singapore: National Museum Art Gallery. Call no.: RCLOS O575 ↩

-

Nayar, P. (1999, December 18). Remembering Kim Lim. The Business Times, p. 22. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Zhuang, X. (2011). Uncommon wisdom: Works by Chng Seok Tin from 1966–2011 (p. 27). Singapore: Nanyang Academy of Fine Arts. Call no.: 709.5957 ZHU ↩

-

Chng, S. T. (2011). A flower, yet not a flower. In Uncommon wisdom: Works by Chng Seok Tin from 1966–2011 (pp. 18–19). Singapore: Nanyang Academy of Fine Arts. Call no.: 709.5957 ZHU ↩

-

Chow, C. (2007, January 18). Putting art out in the open. The Straits Times, p. 53. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Wong, S. (1993, July 6). Back to nature. The Straits Times, p. 11. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The Esplanade Theatre Co. Ltd. (2016). Construction Site 2016. Retrieved from Esplanade Theatres on the Bay website. ↩

-

Prvacki, D. (2015). Marina South Pier Mural 2015. Retrieved from Marina South Pier Mural 2015 website. ↩

-

Pedas is Malay for “spicy”. ↩

-

Sabapathy, T. K. (2013). Fluxion: Art & thoughts: Kumari Nahappan (pp. 120–124). Singapore: Editions Didier Millet. Call no.: RSING 709.5957 SAB ↩

-

Shetty, D. (2015, August 18). Sculptures for SG50. The Straits Times, pp. 4–5. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩