S R Nathan: 50 Stories from My Life

The late S R Nathan published seven books in his lifetime, but his most accessible is probably 50 Stories from My Life. These two selections offer contrasting glimpses of the man who was President of Singapore from 1999–2011.

How I Met My Wife – and Finally Married Her

My wife and I have enjoyed a long and happy marriage. The story of our courtship and engagement is one of persistence against the odds. It began during the Japanese Occupation.

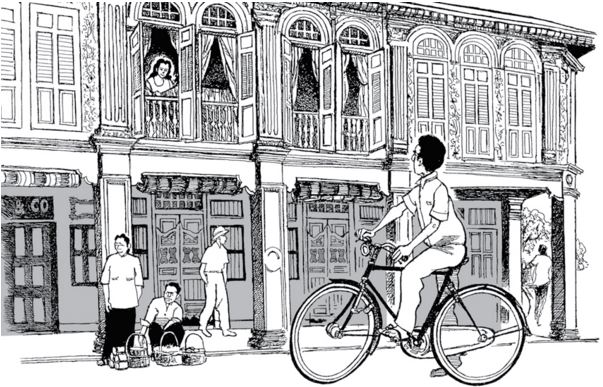

You could say that I married the girl next door, but it took me 16 years to do it. During my childhood in Muar, the adjoining shophouse was occupied by a family headed by one K. P. Nandey, a man with a fiery disposition who tended to smash plates when in a temper. Later, during the Occupation, when I was back in Muar alone, I became friendly with one of the sons of the family. One day, when visiting him, I caught sight of his sister standing at the window of their house. Her name was Urmila, or “Umi” for short.

Before long, while running errands on my bicycle for the Japanese soldiers, I started regularly to go out of my way so that I could pass the front of the house. I only possessed one good shirt at that time. It was mauve in colour, and it made quite an impression on Umi, or so she tells me.

Umi’s parents would not have seen me as a suitable match. My family origins are Tamil. They were Bengali, and they would no doubt have preferred a Bengali suitor, ideally a nice lawyer or doctor. So I started to leave her notes. She would leave her reply, and I would sneak by and collect it.

In due course the family decided to move to Johor Bahru, by which time I was already living there myself. To ingratiate myself I borrowed a truck from my Japanese employer and moved their household possessions overnight. From then onwards, Umi’s father looked on me a little more kindly.

My relationship with Umi’s brother soured – he did not approve of my interest in his sister.

In 1952, Umi applied for a teacher-training course in Britain that would take her away for two years. She was awarded a place, and was all set to leave in August, two months before my own university course started. I think her father was happy to get her away from me for a time.

Her leaving was very painful. She was set to fly from Singapore to Kuala Lumpur, where she would meet up with her Malayan fellow-students before flying on to London. Since we could not meet openly in Singapore, after she took the flight to Kuala Lumpur, I travelled up there myself, where we met and then parted tearfully. We had a photograph taken, showing us together, and vowed to keep in touch by letter.

I was deeply saddened, and cried all the way on the flight back to Singapore. My mother consoled me later, saying: “Don’t be sad. Leave it to God. If he wills, all will turn out according to both your wishes.” And it did.

While she was away in the UK, we kept up with weekly airmail letters. I was always anxious, as I was afraid she might come into contact with someone better than me. It did not happen. She was as steadfast as on the day when we parted.

When Umi returned, her father invited me to go with him to Kuala Lumpur to meet her at the airport, although the journey back to Johor Bahru on the train was a little tense. We could not communicate openly in her father’s presence.

Finally, early the following year, I plucked up the courage to approach Umi’s father, and told him I wanted to marry her.

I thought he would be furious. In fact, he was not. He did not want us to get married immediately. His elder daughter had gone to university. He asked me to wait till she graduated. Umi was impatient, unwilling to carry on as we were for four more years. My own mother was adamant – Umi’s family had treated me well and I must not let them down. “You have already waited 12 years – you will just have to wait another four!” So we did.

Finally, in December 1958, the wedding took place – in fact, two weddings. Umi’s sister got married at the same time. And Umi and I have been together ever since.

Flying with Hijackers

Sometimes even civil servants must be willing to face danger, as I discovered after terrorists hijacked a vessel in Singapore harbour. Fortunately, the incident ended without bloodshed.

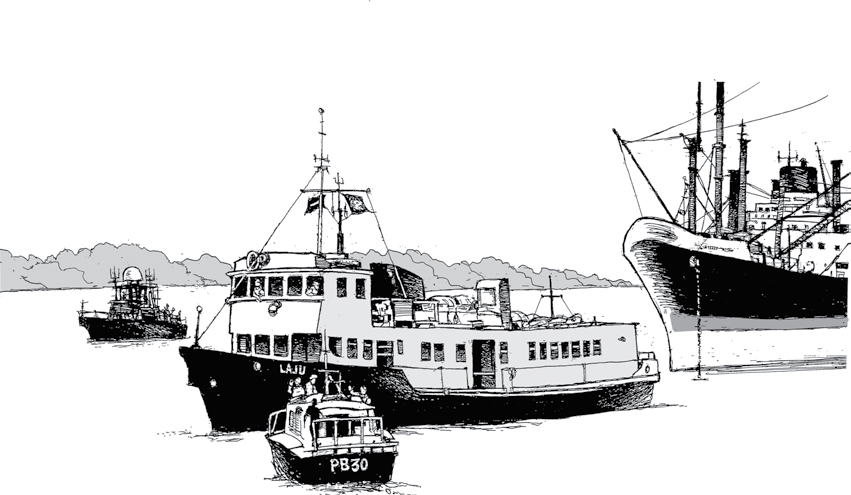

In 1974, when I was director of the Security and Intelligence Division at the Ministry of Defence, hijackers seized the Laju, a small ferry owned by Shell, the oil company. By the time I reached the Marine Police headquarters, the Laju was being shadowed by a police patrol boat. Finally, it came to a halt, surrounded by police, customs and Singapore Maritime Command vessels.

The hijackers put a message in a bottle. They announced they were the “Japanese Red Army and Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine”. They threatened to kill their hostages unless they were allowed to leave Singapore for an “Arab” country. At that stage we did not know who the hostages were, or how many there were.

We learned subsequently that there were four terrorists. Two of them were Japanese and two Arab. Earlier, they had set off explosive charges against four oil tanks on Pulau Bukom. They had unexpectedly been spotted, and had had to make a rapid escape. They had run to the Shell jetty, where they had hijacked the Laju, which was waiting to take passengers. These would have included children crossing from the island to Singapore to attend school. Fortunately, they had not actually boarded the vessel. Five crewmen were being held hostage.

Negotiations were begun, mostly by loudhailer, by Superintendent Tee Tua Ba, head of the Marine Police, stationed on his patrol boat. The terrorists asked for the Japanese ambassador to be summoned. When we didn’t respond, they sent a radio message: “Sunset time is blowing up time.” Finally, when the ambassador appeared, and after some negotiation, they turned against him, threatening that if the Japanese police were involved, blood would flow.

That night, two of the crew escaped by jumping overboard. This gave us much valuable information on the armed status of the hijackers and the number of local hostages still on board.

Lengthy negotiations followed, involving the hijackers, the Singapore authorities, other Arab missions and the Japanese embassy. We were unwilling to fly the hijackers out on a Singaporean plane because that would only have encouraged other terrorists to see Singapore as an easy terrorist target. Proposals to fly them out on a Japanese plane came to nothing. Tense discussions lasted several days, with no solution in sight.

The sixth day brought a new development. Supporters of the terrorists had stormed the Japanese embassy in Kuwait, taking the ambassador and 15 staff hostage. They threatened to execute their hostages, starting with the Second Secretary (one of the diplomatic staff), if the Japanese government did not send a plane to Singapore to pick up the Laju hijackers.

The Japanese government finally offered to send a JAL plane. Although we did not tell the Laju hijackers about the embassy seizure in Kuwait, they finally agreed to be flown out to Kuwait. We insisted they give up their weapons. At last they agreed to give up their arms and explosives at the airport, before boarding the plane. They were to be accompanied by unarmed teams of Singaporean and Japanese officials.

Dr Goh Keng Swee, Defence Minister at the time, instructed me to lead the team of Singapore officials. Our mission was to hand over the Singapore hijackers to the Kuwait authorities to help resolve the situation at the Japanese embassy in Kuwait. As I said goodbye to my family, I did not mention the risks that lay ahead. We were afraid that the terrorist organisation might not let us leave Kuwait, using us as bargaining chips for the release of people in captivity in Israel or somewhere else.

As we neared our destination, I had to spell out to the authorities in Kuwait in a radio message the conditions on which we had undertaken the journey: “… 13 senior officials of Singapore government must alight from the plane before the terrorists in Kuwait are taken on board. Singapore officials will leave plane and proceed straight back to Singapore. Until this is agreed and guaranteed by Kuwait government, the doors of the aircraft must necessarily remain closed. … Japanese crew and two senior officials will remain on board and go with the terrorists to final destination.”

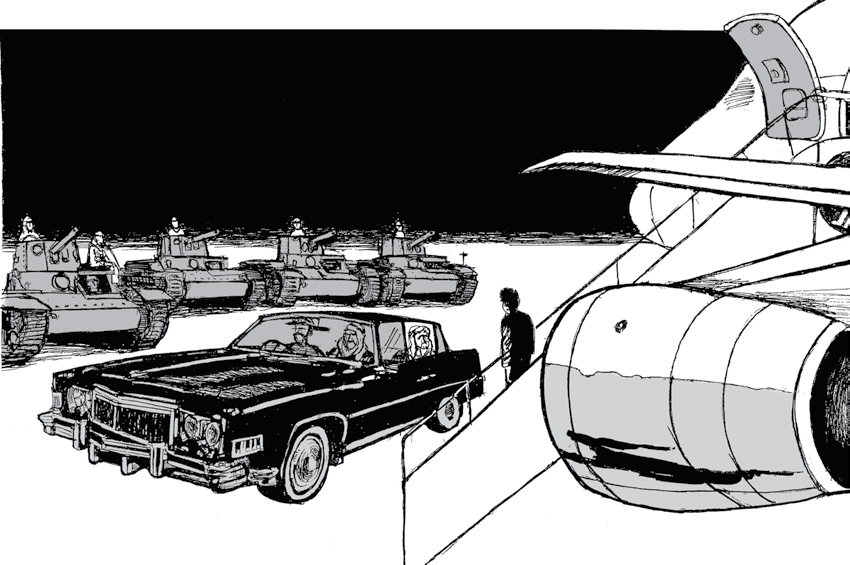

When we landed, the aircraft was surrounded by tanks, armoured vehicles and soldiers carrying automatic weapons. For hours, we negotiated with the Kuwaiti authorities. I was asked to disembark from the plane and take my message in person to a Kuwaiti government minister, who was driven onto the tarmac in his limousine. Long arguments followed, involving the Kuwaitis and the Japanese ambassador to Iran, who had been brought to the scene to represent the Japanese government.

The terrorists who had stormed the Japanese embassy in Kuwait arrived at the airport – and boarded the aircraft fully armed with revolvers and hand grenades. Talking to the Japanese diplomat in Bahasa, which he understood, I persuaded him to insist that they be disarmed before the plane proceeded to its next destination. It was settled that they would keep their side arms but without the bullets – these would be kept in the hold. The Kuwaiti minister would not allow me to speak during their negotiations.

At last came the development we had all been waiting for. The Kuwaiti foreign minister arrived, and told me and my fellow Singaporeans to leave the aircraft. For several hours we were afraid that the hijackers might insist that we be returned to the aircraft as hostages, so we made ourselves scarce. However, that night we were flown safely by Kuwait Airways to Bahrain, and returned home from there on Singapore Airlines. Both groups of terrorists were flown on later to South Yemen.

The whole episode ended without bloodshed. It was good experience for me, the various ministries involved, the security service, the police and the military. While the decision to give the Laju hijackers safe passage out of Singapore attracted some criticism, we believed it was right. We wanted to minimise any likelihood of a terrorist group picking a quarrel with Singapore and seeking retaliation. In government you often have to make difficult decisions about serious problems with little accurate information at your disposal, and under great time pressure.

S R Nathan: 50 Stories from My Life captures major milestones in the personal and official life of the late former President of Singapore (b. 3 July 1924−d. 22 August 2016). Written with a younger audience in mind, and illustrated by Morgan Chua, a former political cartoonist with the Far Eastern Economic Review, the book will appeal to anyone interested in Singapore and its history.

S R Nathan: 50 Stories from My Life (paperback, 184 pages) is published by Editions Didier Millet and retails at $19.90. It is available for loan and reference at the Lee Kong Chian Reference Library and branches of all public libraries (Call no.: RSING 959.5705092 NAT).

OTHER PUBLICATIONS BY S R NATHAN

S R Nathan in Conversation with Timothy Auger

Editions Didier Millet, 2015

Call nos.: RSING 959.5705 NAT and SING 959.5705 NAT

An Unexpected Journey: Path to the Presidency

Editions Didier Millet, 2011

Call nos.: RSING 959.5705092 NAT and SING 959.5705092 NAT

Why Am I Here?: Overcoming Hardships of Local Seafarers

Centre for Maritime Studies, National University of Singapore, 2010

Call nos.: RSING 331.7613875095957 NAT and SING 331.7613875095957 NAT

The Crane and the Crab

Epigram Books, 2013

Call nos.: JRSING 428.6 NAT and JSING 428.6 NAT

Winning Against the Odds: The Labour Research Unit in NTUC’s Founding

Straits Times Press, 2011

Call nos.: RSING 331.880959957 NAT and SING 331.880959957 NAT

Singapore’s Foreign Policy: Beginnings and Future

MFA Diplomatic Academy, 2008

Call no.: RSING 327.5957 NAT