1960s Fashion: The Legacy of Made-To-Measure

The changing face of fashion in Singapore is the subject of a new book called Fashion Most Wanted. This extract recalls how the advent of TV impacted new fashion trends in the 1960s.

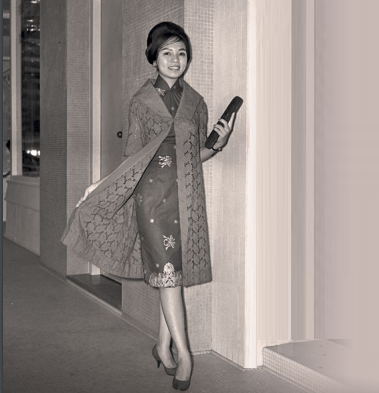

A model wearing a creation from Janilaine, one of Singapore’s most prominent made-to-measure clothing shops in the1960s. Courtesy of Singapore Press Holdings.

A model wearing a creation from Janilaine, one of Singapore’s most prominent made-to-measure clothing shops in the1960s. Courtesy of Singapore Press Holdings.The neighbourhood dressmaker who relied on paper patterns and her pedal-powered Singer sewing machine, the exacting Shanghainese tailor who draped the body and crafted by hand, the Indian tailor – immaculate in a crisp white shirt and spotless dhoti – who arrived at your doorstep to take your measurements. These were the “magicians of style” in Singapore half a century ago.

Says retired personal assistant Carol de Souza: “They only needed to see a photo from Vogue or another magazine in order to turn out a dress that looked exactly like the photo.”

She ought to know. From her teenage years until store-bought fashion became readily available in the 1970s, de Souza had to rely on tailors for all her sartorial needs, from career clothes to her wedding trousseau. And they never let her down. When she took all her Singapore-tailored outfits with her to Houston, Texas, where she had moved to in 1981, “the cheongsams from Mode-0-Day were always a hit with the guys!”

In the early 1950s, when the local retail scene was still undeveloped, the various ethnic groups would don their own cultural garb, while the Eurasians and British, Australian and New Zealand expat wives would be dressed in foreign fashion imports. These were only available from a handful of boutiques in Singapore.

Fashion entrepreneur Judith Chung, who was a fashion reporter for The Sunday Times in the 1960s, still remembers one owner of such an exclusive establishment: the arresting Doris Geddes, an Australian who ran The Little Shop at the Raffles Hotel from 1947 for 30 years. According to the 1967 Olson’s Orient Guide, her speciality was “high fashion with an exotic touch” as she was a dressmaker as well as a retailer of “fine imports” from Asian craft to European couture dresses.

Geddes’ shop had upped the ante for Singapore tremendously in 1957 when Elizabeth Taylor, who was visiting Singapore with her third husband, film producer Mike Todd, wore a fitted strapless dress of Geddes’ own design to a Raffles Hotel dinner. According to a report in famoushotels.org, Taylor was overhead screaming at Geddes the day after because the dress had split at the seams in the middle of dinner. Not one to lose her cool, Geddes had reportedly retorted: “You should not have insisted on this dress, it was too small for you, I told you so!”

Tailor-made

For most Singapore-born ingenues and their society matron mums, like Carol de Souza and her mother, made-to-measure was the name of the game in the local fashion stakes. Their clothes-shopping routine would entail trooping to the grande dame of department stores in Singapore – Robinsons at Raffles Place – for its McCall’s and Butterick paper patterns.

A trip to a bookshop or an Indian-run five-foot-way (pedestrian walkway) magazine stand could also arm one with magazines such as Burda, Lana Lobell, So-en, Vogue or Women’s Weekly, just to name a few, with the best pictures of the new trends.

Following that, the next stop would be High Street to dig through bales of materials at Aurora, Metro, Modern Silk Store and S.A. Majeed. If you still could not find the right fabric, there was also Chotirmalls or Peking Silk Store on adjacent North Bridge Road. And People’s Park in Chinatown, as well as night markets all over Singapore, where de Souza recalls that she and her mother would always end up buying “bags and bags of fabric – more than what we went looking for”.

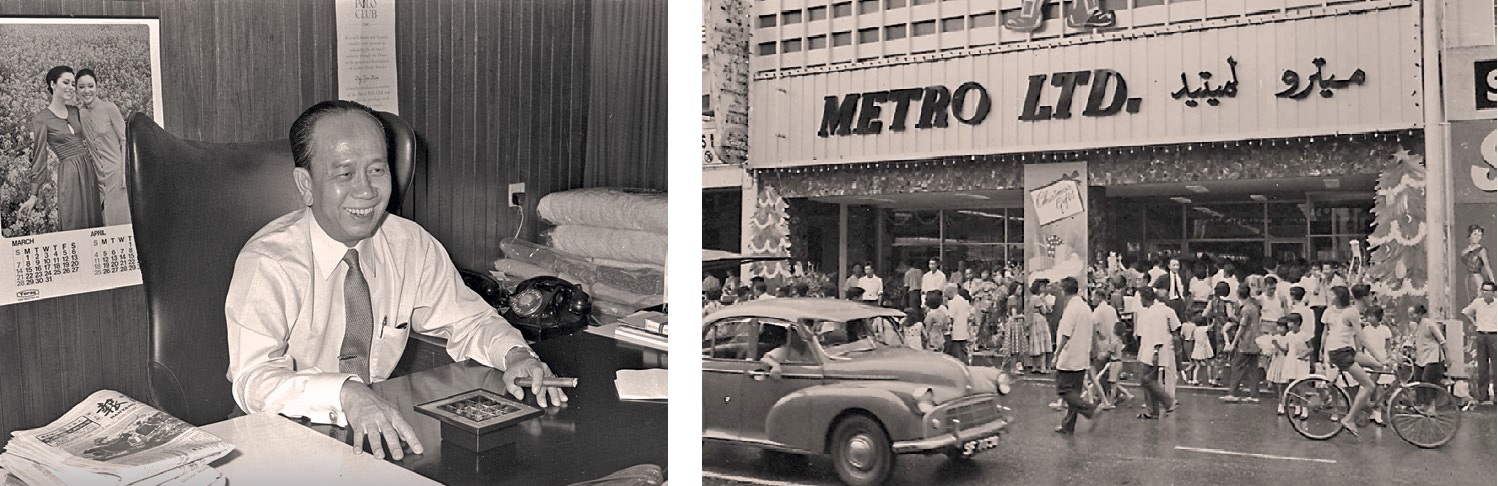

As a 10-year-old accompanying his 29-year-old tai tai mother Elizabeth Lee on her shopping trips in 1966, Dick Lee can still vividly recall that “the old Metro (High Street) had fabric counters in front, and cosmetics counters behind them. Each fabric shop had long tables with bales of fabric”.

Colour and prints galore! This must explain why the polymath creative director still exhibits a fondness for riotous prints and colours in his dapper personal style.

According to Metro’s Executive Chairman, Wong Sioe Hong, her father Ong Tjoe Kim thought it would be a smart move to be the only fashion retail shop surrounded by a row of wholesale fabric stores when he founded his single-unit store on High Street in 1957. He called it Metro, after his first store in Indonesia, and he was proven right when he had to expand to the unit next door to capitalise on his booming business.

Wong recalls: “He was literally a oneman show – owner, buyer, operator. It was a small store – only 8,000 sq ft. Metro was the first department store to import fabrics from the US. My father was the first to bring in lace from France and silk from Italy.”

In the 1960s, tailoring shops abounded in central Singapore, from Tiong Bahru to Tiverton Lane off Killiney Road. But many an enterprising home-based dressmaker could also be found in the new HDB flats springing up in Queenstown and Toa Payoh, as well as in landed properties in private estates all over Singapore.

Standard tailoring charges then were $6 for a dress without lining, $12 with lining and $20 and above for tailoring with expensive materials like chiffon, lace, satin, silk and voile, as well as for long gowns.

A Singer or an Elna sewing machine was not only indispensable to every household; it was also regarded as a prized family heirloom – to be passed down the generations. Just like the one Gloria Barker – wife of Singapore’s first Law Minister, the late E.W. Barker – inherited from her mother, according to her interior decorator son, Brandon.

Brandon Barker was a part-time model in the 1960s so his mother taught him how to cut and sew his own clothes. Thanks to this, he was able to make Oxford bags, those loosely fitted trousers with wide legs, for himself, when he found that those made by professional tailors “never quite fit right”. Barker got so good at dressmaking, he could even sew gored skirts – a popular fashion item back then – for his younger sister, Gillian, also a part-time model.

London Calling

Paris might have been the fashion capital that used to dictate clothing trends to an adult audience, but musician and former disc jockey Vernon Cornelius says that London became the 1960s youth capital of fashion. He remembers young people dressing up “according to what was going on and the music of the time”.

It signalled “the start of style consciousness for Singaporeans”. Everyone wanted to imitate the hairstyles and look of musicians from Cliff Richard and The Shadows (neatly combed back hair, skinny suits) to The Beatles (heavy fringes, Flower Power caftans with beads) and The Rolling Stones (longish hair, psychedelic styles).

Youths became what he calls “freeform and individualist in their dress, aping [the West] in a sense, but not copying exactly. We took ideas, sort of improvised something and made them our own”. But as times were still tough in the days of a newly independent Singapore, he adds that most young people like himself had to save for weeks or months to array themselves in mod looks as a “sincere form of expressing our own identity”.

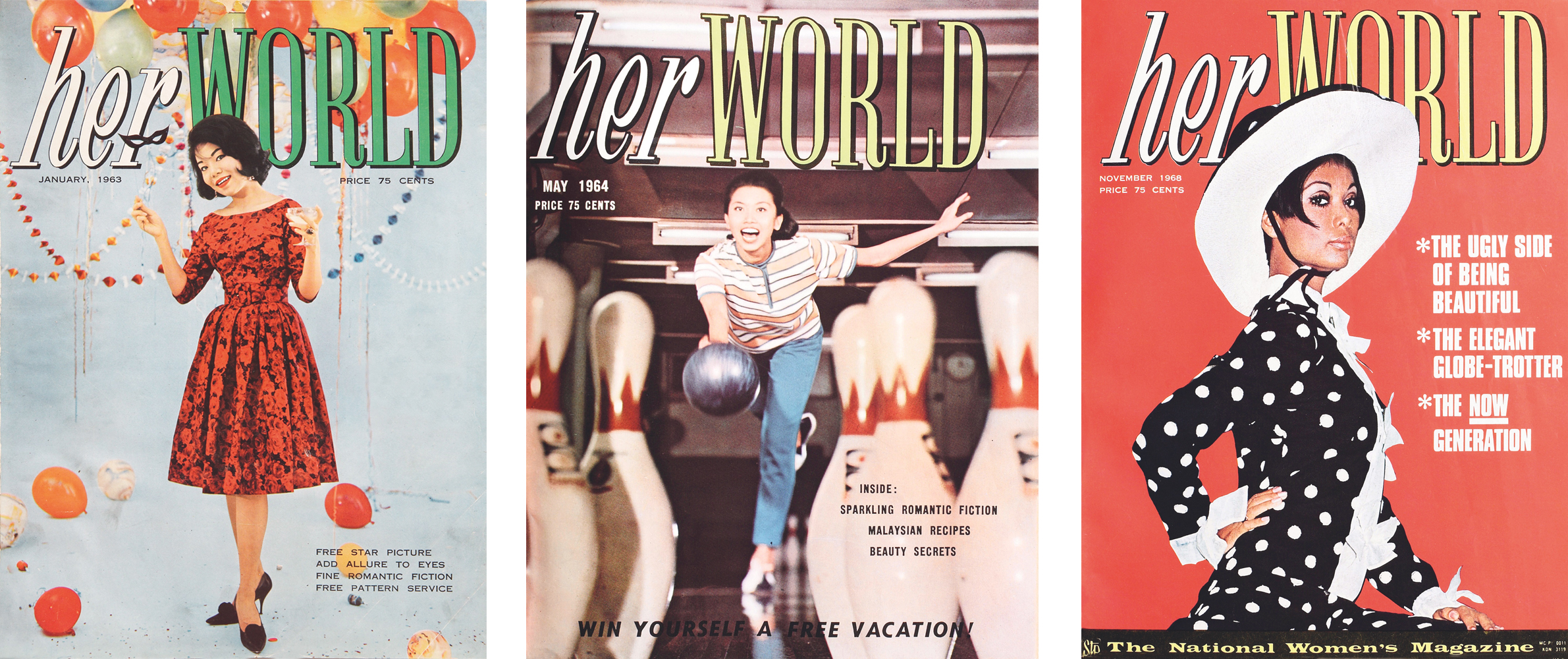

The Swinging Sixties was indeed a time of youthful exuberance and experimentation, thanks to a flourishing world economy and unimaginable breakthroughs – from the first man walking on the moon to the invention of the Concorde and the world’s first successful heart transplants. Television was launched in Singapore in 1963, and the first person to appear on screen was Minister for Culture S. Rajaratnam, who declared: “Tonight might well mark the start of a social and cultural revolution in our lives.” Indeed.

One of the first types of programmes televised that evening was a variety show into which fashion and lifestyle elements would eventually be incorporated. Featured would be the young nation’s first generation of homegrown fashion stars.

Freelance hairstylist Francis Raquiza who had trained under Roland Chow, Singapore’s most celebrated hairstylistcum- fashion designer of that era, can never forget that as there was only black-and- white television then: “It was strange when (Roland) demonstrated and talked about what lipstick colour would match what colour dress – and everything on the screen was black and white!”

In 1967, it was reported that 50 percent of British women’s fashion sold was to the 15 to 19 age group. Carnaby Street, in London’s Soho district, was identified as the epicentre of the global youth-quake. So it was no wonder that the grooviest of 1960s fashion boutiques – including the “mini skirt” creator, Mary Quant’s flagship shop – were congregated there.

In 1966, Carnaby Street was splashed on the cover of Time magazine, sealing London’s credibility as the capital of cool. Among the many Singaporeans who noted Time’s report and were quick to flock there was Alice Fu, who later became the first head buyer of Tangs (formerly C K Tang) from 1982 to 1996. In the late 1960s, as a secretary at a travel agency, she could get discounted air tickets to London. “So I took my mum to London. We told ourselves we had to see Carnaby Street, and we bought Mary Quant halter tops, chunky platform shoes, high boots, and maxi dresses,” she recalls.

Fu was inspired by her Carnaby Street experience of affordable fun fashion but was put off in Singapore, having to visit men’s tailors like Kingsmen to make bell bottoms, Khemco’s for shirts and other assorted tailors for mod dresses, miniskirts and hot pants. She told herself, why not open a shop with like-minded friends? So, together with two partners, Tan Beng Yan, who later founded the Tyan fashion group, and a girlfriend named Joanna, they launched the Saturday’s Child fashion label.

“It was meant to emulate the ready-to- wear London look and we had to ‘design’ all our own clothes – hipster pants, halter tops, mini dresses – based on what we saw in magazines. I remember we had the tailor from Trend moonlighting for us. Her name was Ah Geok,” she says.

Rabiah and Her Sisters

If Ah Geok made “magic” creating Singapore’s earliest off-the-peg kaleidoscopic 1960s styles from magazine pictures, no one else was better at modelling and marketing such free-wheeling looks as the decade’s most iconic pin-up girl, Rabiah Ibrahim. That is unless, of course, they were her equally fashionable and famous sisters and partners, Carol, Fatimah and Faith.

Faith Ibrahim put Singapore’s name on the international modelling scene when she became Pierre Cardin’s house model and was known as Anak in the late 1960s. After marrying the 13th Duke of Bedford, she became the respectable London-based Lady Russell.

According to Rabiah Ibrahim, whose father was a doctor, her siblings and herself “had travelled more than most of her peers, and never wanted to follow the crowd”. This was not confined to only their dress sense. After becoming a mother of three sons, she still found the time and energy to run her flourishing fashion empire of Trend boutiques for more than 20 years, guided by her sense of “adventure, creativity, glamour and fun”, as she put it, in the 1991 annual edition of Her World magazine.

At its most successful, there were also Trend shops in San Francisco and Hong Kong. By the 1980s, when she migrated to Perth to become a Bible teacher and sold her Trend business to fellow fashion entrepreneur Chan Kheng Lin, it had become a 23-store, multi-million-dollar business.

Fashion Pioneer

The Ibrahim sisters were not the only fashion beacons in a Singapore that was experiencing a cultural awakening with a fervency to modernise, driven as it was by a rapidly evolving socio-political climate.

In a 2015 Straits Times report, architect Tan Cheng Siong, who designed the iconic conservation Pearl Bank Apartments in 1976, said that even as a youth in the 1960s he had the awareness that Singapore had “always wanted very badly to be modern”.

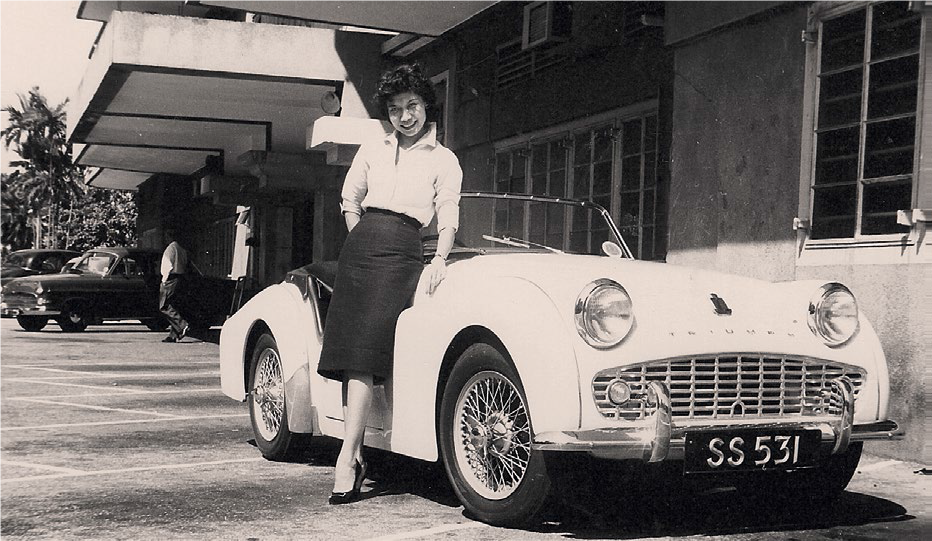

Modern would certainly have described a young Phila Mae Wong when she was about to set off to the US for her university studies in 1961. In her teens, she had already become a competitive bowler, balance beam gymnast and one of Singapore’s champion water skiers. As a little girl, encouraged by her mother, she would re-design all her dolls’ clothes so that they would look more modern.

Before Wong could graduate from university, she became an associate buyer for her mother’s fashion imports shop named Vanity Fair at Raffles Place, and even started her own boutique, The Look, within her mother’s store, promoting affordable sportswear-inspired American brands as well as London’s youthful Carnaby Street style. In 1963, she explained to Her World reporter Doreen Chee that “Paris fashion can be the very epitome of elegance but it is for the elite upper strata of society. American fashion is more practical and more saleable”.

If Phila Mae Wong was ahead of her time, it was because she had been trained by the best – her mother, none other than the indomitable Eunice Wong, who was not only one of Singapore’s successful Grand Prix drivers of the 1960s, but also an unstoppable one-woman entrepreneurial machine. In the 1950s, Phila Mae’s grandfather opened the Lee & Fletcher trading company along Orchard Road (where the Concorde Hotel Singapore now stands).

Emulating her father, and always reflecting her impeccable taste and grasp of the changing life and times, Eunice Wong was to open her own chain of retail shops as soon as she came of age. Perhaps to help promote her father’s Elna sewing machines, she first opened two ready-made and custom-tailored fashion boutiques in Shaw Centre and at Fitzpatrick’s supermarket (where the new wing of Paragon now stands) and named them Elna Boutique. As hairstyles changed from bouffant “helmets” to sleek swingy, geometric styles, she also opened two hairdressing salons at High Street and in Cathay Building.

By 1965, realising that jeans were on the cusp of becoming ubiquitous for the younger generation, Eunice Wong ventured into a unisex Jeans East West shop at 104 Orchard Road (near the Lee & Fletcher head office at the Concorde Hotel) with her son, Phila Mae’s brother, Vincent. He used to make his own tie-dye T-shirts to sell with the California West brand of jeans that they stocked. “All his girlfriends were slaves,” Eunice Wong recounts, “they’d do tie-dye T-shirts for his shop. Their target market was rich kids who could afford to pay $30 for jeans at that time, it was a lot of money”.

Still fresh with ideas, Eunice Wong opened not one but two eponymous lifestyle and gift shops in Orchard Road. A final home furnishings shop on Orchard Road – sandwiched between C K Tang and Fitzpatrick’s, where the new Glamourette designer boutique was opened by Siauw Mie Sioe (more popularly known as Mrs Choong) in 1958 – helped to transform Orchard Road from a laidback street of sprawling cemeteries and fruit plantations into Singapore’s premier shopping haunt over the course of the 1960s.

Named after its fruit tree plantations and nurseries, Orchard Road was bordered by monsoon drains that invariably overflowed into the roadways. This caused decades of flooding every Christmas, which coincided with the year-end monsoon rains, until its glitziest makeover in the noughties transformed it into the modern retail wonderland, with wide pedestrian boulevards, that it is today.

Back then, from Orange Grove Road to Scotts Road, impressive expatriate homesteads used to alternate on both sides of the road. Facing the new three-storey C K Tang store – that had been constructed in 1948 on a former nutmeg plantation – was the Tai Shan Ting Cemetery (where Ngee Ann City and Wisma Atria now stand).

After C K Tang was up and running, fashion boutiques such as Antoinette and Buttons and Bows, stocking imports from England and Europe, opened on Orchard Road too. Steadily thereafter, such retail and lifestyle “action” continued to sprout between Scotts Road and Killiney Road.

Equatorial Singapore obviously had enough numbers of the glamorous jet set living on its shores to have its own furrier shop Ali Joo, which used to be located in the original Heeren Building at the corner of Orchard and Cairnhill roads. Cozy Corner Cafe nearby was where dating couples went for Western meals. The defunct Prince’s Hotel Garni, just after Bideford Road, held afternoon tea dances for young people to rock and roll, jive and cha-cha-cha the afternoon away.

At the spot where The Centrepoint stands today was the popular Magnolia Milk Bar, where the baby boomers in Singapore were weaned on milkshakes, ice-cream sundaes and banana splits. The current site of Orchard Central was once an open-air carpark that transformed nightly into a kerosene-lit hawker centre with some of the most delicious local food fare. In 1978, it was closed down by the government due to hygiene concerns.

In the Mood for Cheongsam

The fashion revolution of the 1960s would all but wipe out the appearance of traditional garments such as the sari and sarong kebaya at events other than weddings. But it was a completely different story with the cheongsam.

Phila Mae Wong’s thrice-married aunt, the late Christina Lee – voted by Vogue magazine as one of the most beautiful women in the world in 1965 – had a part to play in this. She was the youngest of the four beautiful daughters from the illustrious Lee family while Phila Mae’s mother, Eunice, was her eldest sister. At the time when her looks were celebrated by Vogue, Christina Lee was married to cinema magnate Loke Wan Tho and the celebrity couple was often captured in the headlines – he in a sharply-tailored Western suit, she in a gorgeous cheongsam.

The 1960 hit Hollywood movie, The World of Suzie Wong, starred Nancy Kwan wearing a series of cheongsams with thigh-high slits. The movie turned the actress into an international pin-up girl, who quickly became known as the “Chinese Bardot”, in reference to the 1960s French screen siren Bridgette Bardot.

Together, the Asian cinema mogul’s stunningly beautiful wife and the Hollywood movie star-turned-sex symbol gave a fillip to the cheongsam, which has made it much coveted by the stylish set, Western or Asian, ever since.

With the advent of air-conditioning in Singapore, Christina Lee started to design her own Western-style coats, jackets and stoles to complement her cheongsams. Taking her cue from the sensational miniskirt of the 1960s, and Roland Chow, who had also designed a mini cheongsam, the hemlines of her own were fashionably cropped at thigh level.

As for designer Thomas Wee, learning how to make exquisite cheongsams from his Shanghai-trained tailor mother at the age of 14 may have been his entry into the world of dressmaking, but it was a wedding gown that Thomas had created for his then supervisor’s wedding that led to his serendipitous switch from working as a pharmacy dispenser to becoming a fashion boutique assistant. His first retail posting was at Flair Boutique along Tanglin Road (where the St Regis is now).

That was, Thomas points out, Singapore’s original fashion street before it was overtaken by Orchard Road in the 1980s. A few doors away from Flair were House of Hilda and Mode-O-Day; the latter is still operating today within Tanglin Shopping Centre, making wedding and evening gowns as well as cheongsams for a new generation of society ladies such as Paige Parker. She told The Straits Times that she had two cheongsams tailored at Mode-0- Day in 2015: a red lace cheongsam for her 40th birthday and a customised pink lace one for the Chinese Women’s Association’s 100th Anniversary Charity Gala.

For young career girls and the trendy young scions of well-to-do Singapore families, the holy grail of 1960s fashion were Biba and Mary Quant of London. Quant is immortalised today as the originator of the miniskirt, while Barbara Hulanicki’s Biba fashion emporium on Kensington High Street was dubbed the sexiest shop in the world by London’s Daily Mail newspaper. Today, Biba’s signature style would be described as being a blend of Mary Quant’s mod look with Laura Ashley’s floral fashion and Topshop’s edgy style.

Choong and Sons

An appetite for modern 1960s fashion not only spread among the women throughout Singapore, but to the men as well. Even kampung boys dressed like peacocks in colourful fashion, with collarless jackets and pants that flared over boots with high heels, just like the girls. Shirts or ties became vividly printed and lapels got more exaggerated as trouser legs widened.

Clothing became increasingly “unisex” as men and women shopped at the same boutiques for similar-looking items or had them made by the same tailors. This is why when Siauw Mie Sioe’s husband Francis Choong received a parcel of “flower power” ties from his eldest son

K C, who was studying in London in the 1960s, he decided to try and sell them in his Caprice men’s shop in Ngee Ann Building on Orchard Road.

When they sold out, it was the sign that he and his wife needed to change their business from traditional tailoring to retailing off-the-peg fashion imports from leading European brands of the day. In 1958, Mr and Mrs Choong – as the husband and wife team were better known as – had been prescient enough to close their Seasons Shanghai tailoring shop in Middle Road to open Glamourette, the first luxury multi-brand boutique in Singapore, at Fitzpatrick’s. They already had an inkling that Orchard Road would become fashion’s most happening street in Singapore, and were catching on to the next big thing – the trend for ready-to- wear clothing.

Before long, Mr Choong was retailing jersey-knit men’s shirts from the Parisian Montagut label at Caprice and Mrs Choong had brought in Biba, Bill Gibbs, Jean Muir and Mary Quant to Glamourette. However, their younger son Jacob K.H. recalls that it was when designers experimented with shiny new waterproof materials with a futuristic look using PVC and Perspex to create “Wet Look” fashion that his parents found they had hit upon their bestsellers of the 1960s.

Fashion Most Wanted: Singapore’s Top Insider Secrets from the Past Five Decades was written by John de Souza, Cat Ong and Tom Rao. All three authors cut their teeth on Singapore’s fashion scene in the 1980s as writers and editors for The Strait Times as well as leading fashion and beauty magazines such as Her World, Elle and Marie Claire. They continue to keep a pulse on the ever evolving fashion scene today.

References

De Souza, J., Ong, C., & Rao, T. (2016). Fashion most wanted: Singapore’s top insider secrets from the past five decades. Singapore: Straits Times Press Pte Ltd. Call no.: RSING 746.92095957 DES

Lee, V. (2015, November 16). The Life interview with Lim Chong Keat. The Straits Times. Retrieved from Factiva via NLB’s eResources website.

Olson, H.S. (1967). Olson’s orient guide. Philadelphia, New York: J.B. Lippincott Company. Not available in NLB holdings.

Powell, P.& Peel, L. (1988). 50s and 60s style. Grange Books, Quintet Publishing Ltd: Groovy Gear. Not available in NLB holdings.

Ruzita Zaki. (Interviewer). (1996, February 13; 1996, February 28). Oral history interview with Vernon Christopher Cornelius [Transcript of Recording No. 001711, Reels 15, 16, 17]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website.

The Most Famous Hotels in the World. (1986–2016). Raffles Hotel: Famous guests. Retrieved from The Most Famous Hotels in the World website.

Singapore’s own Twiggy Rabiah. (1991). In Her World Annual 1991: 30 years of style (A special anniversary issue). Singapore: Times Publishing. Call no.: RCLOS 052 HWA