From Pauper to Philanthropist: The Tan Tock Seng Story

Sue-Ann Chia traces the classic rags-to-riches story of a vegetable seller turned land speculator who left a hospital named after him in Singapore.

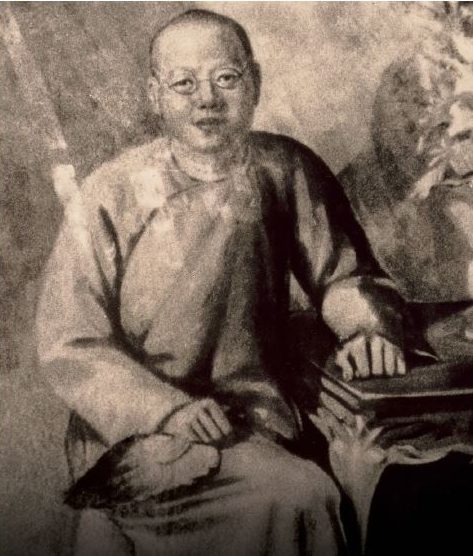

Portrait of Tan Tock Seng, c.1840. Margaret Tan Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Portrait of Tan Tock Seng, c.1840. Margaret Tan Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.In 1989, a large and elaborate grave on the grassy slopes of Outram Hill was “discovered” by Geraldine Lowe, a well-known Singaporean tour guide. Overgrown with a tangle of weeds and covered in dirt, the decrepit tomb appeared abandoned.

This was the resting place of Tan Tock Seng, who bears the distinction of having one of Singapore’s largest hospitals named after him. Unfortunately, that is the only detail that most people know about the noted philanthropist – a forgotten pioneer, much like his grave.

Lowe, who stumbled upon the grave during a heritage hunt, said in an interview, “It’s a shame that nobody is taking care of the tomb. It is on an almost inaccesible slope in Tiong Bahru. Something should be done about it.”1

Since the rediscovery of the grave, Tan’s descendants have been tending to his tomb and a major sprucing up of the site was carried out in 2009, according to a heritage report on Tiong Bahru.2

The pioneer’s great-great-grandson Roney Tan dismissed claims that his forefather’s grave was ever neglected. “Tan Tock Seng’s grave was never lost,” the company director said in an interview in 2013. “The truth is, my family and I always knew where it was. Growing up, my dad used to bring me to the gravesite at Outram Hill once or twice a year.” He explained, “It was simply not possible to adequately maintain a grave just once a year, adding “Which is why I called a meeting of the family some years back and said, “Let’s maintain it regularly, not just at Qing Ming. So now, there is a fund to maintain the gravesite.”3

Tan Tock Seng, who had six children – three sons and three daughters – with wife Lee Seo Neo, has a remarkable genealogy that spans over eight generations with more than 2,500 descendents scattered across the globe.4

From Vegetable Seller to Philanthropist

Tan Tock Seng was born in Malacca in 1798, the third son of an immigrant father from Fujian province in China and a local Peranakan (Straits-born Chinese) mother. When he was 21, Tan boarded a ship that sailed south to Singapore in search of the proverbial fame and fortune. He arrived in 1819, shortly after Stamford Raffles had established a British trading outpost on the swamp-filled island.5

Tan was one of the earliest immigrants in Singapore, and in a matter of a few years rose to become one of the most wealthy residents and a pioneer community leader of the Chinese population. But his story is quite unlike those of his successful contemporaries.

In her book, A History of Singapore 1819–1988, historian Constance Mary Turnbull wrote: “Most of the influential early settlers were already prosperous when they arrived [in Singapore] and did not fit the popular rags-to-riches success stories of penniless youths rising by hard work and acument to wealth and eminence. The Hokkien Tan Tock Seng was an exception.”6

It is not known what Tan’s father did for a living in Malacca. Even though most Peranakans were wealthy, Tan’s family was said to be “not rich”. “Tan Tock Seng must have been a poor youth, doing perhaps odd jobs or even selling fruit, vegetables and poultry in the market in Malacca to help augment his father’s income to support the family. His mother would not have undertaken any employment as most nonyas [Straits Chinese ladies] were housewives,” wrote author Dhoraisingham S. Samuel in a biography of Tan.7

Tan’s elder brother Oo Long eventually joined him in Singapore. The fate of his two other brothers remain unknown; all we know is that one of them went to China. What is certain is that Tan arrived in Singapore “with no worldly goods, his only capital being industry and economy”, reported The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser newspaper in March 1850.8

But good fortune favoured the enterprising and those who were willing to work hard in the fledgling port city that was teeming with opportunities. Soon after his arrival, Tan set up a roadside stall selling vegetables, fruits and poultry, bringing produce from the countryside to the city. Within a matter of eight years, by 1827, he had saved up enough to open up a shop at Boat Quay, where the Chinese community originally settled. Tan’s big break came when he met J.H. Whitehead, a partner in the British trading firm of Shaw, Whitehead & Co. Through a combination of sheer luck and an astute joint venture in land speculation, Tan became a very wealthy businessman and landowner.9

Tan’s impressive land bank included 50 acres of prime space where the railway station at Tanjong Pagar was located as well as swathes of land stretching from the Padang all the way to High Street and Tank Road. He also owned a row of shophouses at Ellenborough Building. Together with his brother Oo Long, Tan also owned a nutmeg plantation and an orchard. The 14-acre fruit plantation was located opposite the old St Andrew’s Mission Hospital in Tanjong Pagar.10

Tan’s great-grandson Tan Hoon Siang, a rubber tycoon, said his ancestor could speak English – which made it easier for him to hobnob with the elite British community and expand his business contacts, but it is not known if he could write in English. Tan’s letters, penned in cursive English to the British Governor, were always signed in Chinese and accompanied by his Chinese seal. It is very likely that he employed a secretary to write his letters in English.11

As Tan grew in stature and influence, he was asked to help settle disputes between Chinese migrants. This earned him the title of “Captain of the Chinese”, and he became the first Asian to be appointed Justice of the Peace by then Governor William John Butterworth.12

According to The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser in March 1850: “Much of his time was engrossed in acting as arbitrator in disputes between his countrymen, and many a case which would otherwise have afforded a rich harvest to the lawyers, was through his intervention and mediation nipped in the bud.”13

Locking Horns with the British

The year was 1844. Singapore “was a merchant’s delight” with “huge profits to be made in commercial ventures”, “but the streets of the island also reeked with diseased and suffering people”, according to the New Nation in September 1974.

This prompted a sharply worded editorial by Wiliam Napier, editor of The Singapore Free Press: “A number of diseased Chinese, lepers and others frequent almost every street in town, presenting a spectacle which is rarely to be met with even in towns with a pagan government, and which is truly disgraceful in a civilised and Christian country, especially under the government of Englishmen.”14

Something had to be done and soon. For several years, demands had been made on the British to devote more resources to help the sick and destitute in Singapore, but it was largely ignored.15 Finally, in 1834, the government relented and imposed a tax on the sale of pork, using the proceeds to build a Chinese Poor House. However, when the British later needed more space to house the rising convict population, it decided to convert the poor house into a jail.16

Meanwhile, attracted by the opportunities in Singapore, Chinese immigrants began to arrive in large numbers, turning the island, especially the Chinatown enclave, into a cesspool of diseases, including malaria, cholera, smallpox, leprosy and tuberculosis. George Francis Train, an American visiting Singapore in the mid-19th century, described the desperate situation of the new migrants:

“Captain Hays says the examination of passengers on board the junks that take them off to the ship is too revolting for description. All men over 35 years, or who, after they have been stripped stark naked, show the least sign of disease upon their persons are rejected, and these poor creatures brought a long way from the interior of China by ‘crimps’ of their own nation – who get $10 for bringing down all of what they term healthy cattle – are turned ashore to perish of starvation or die a lingering death by exposure.”17

As health conditions deteriorated on the island, the saving hand came from the Chinese community. A kind-hearted merchant by the name of Cham Chan Sang started a fund for a hospital by bequeathing a sum of 2,000 Spanish dollars – the currency of the time – when he died in January 1844. To make the hospital a reality, Tan topped it up with another 5,000 Spanish dollars from his own pocket.18

This initiative, however, likely embarrassed the British government in Bengal, India.19 They accused the Chinese community of having an agenda, going so far as to suggest that a new tax be levied to construct the hospital instead of graciously accepting the donation.20

In response, Tan rallied a group of prominent residents, including Europeans, who sent a petition to the government, outlining the sentiments of the community. The petition raised several key points.

First, the Chinese community was anxious to build this “Pauper Hospital”, not to please their European masters but to ease the suffering of their clansmen. Second, while it was “absolutely necessary” to build this hospital, there was no need for the British to profit from its construction by the imposition of taxes. Third, the government should ensure that there is no further importation of sick and destitute people into the colony. And, finally, the government should “afford their countenance and support” the cause.21

In his book, An Anecdotal History of Old Times in Singapore (1902), Charles Burton Buckley commented: “The Government had been slow to recognise the necessity of providing a hospital and… it was… left to generous-minded individuals to do what they could to alleviate the necessities of the sick poor.”22

Tan’s tenacity in building this hospital not just for the Chinese, but for all races, was clear. Nothing was going to stop him, not even the government.

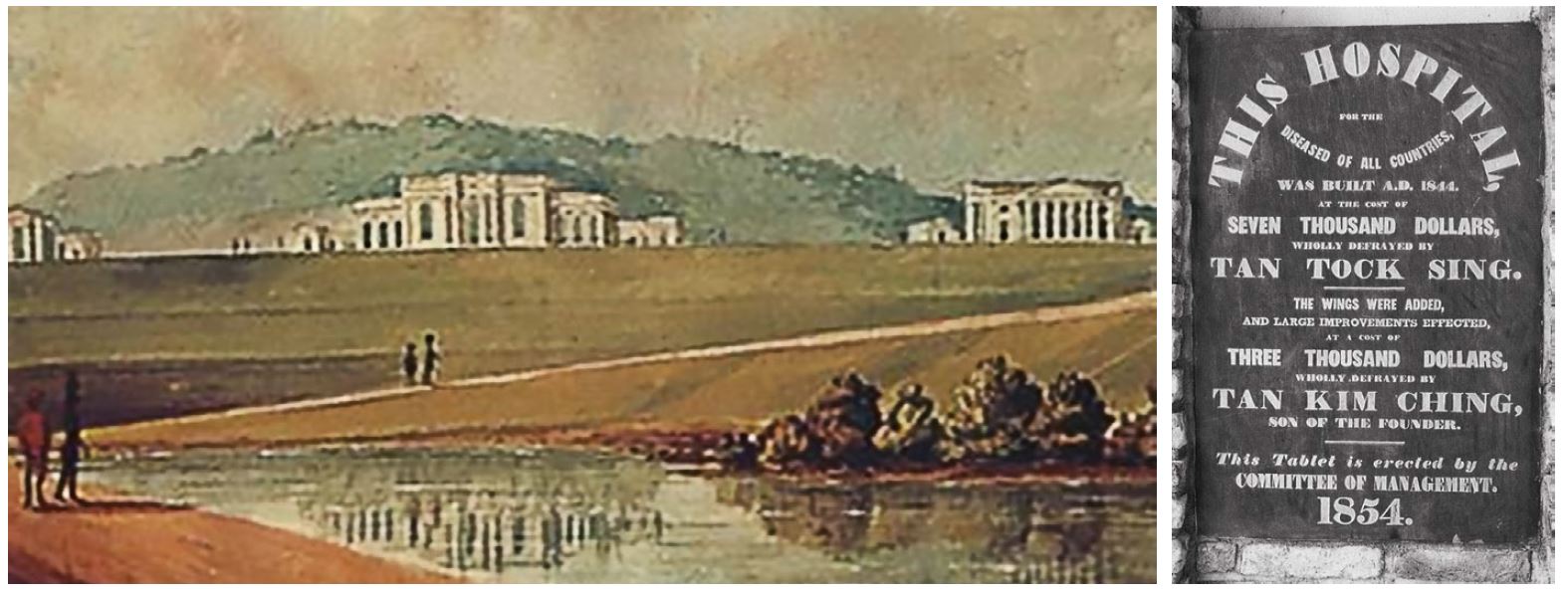

On 25 May 1844, the foundation stone for the hospital, then called “The Chinese Pauper Hospital”, was laid at its original location at Pearl’s Hill. Tan was the founder and financier of the hospital, affectionately nicknamed “Tocksing’s Hospital”. Although the building was completed in 1846, it only operated as a hospital from 1849 onwards as the government used it as a temporary convict jail in the intervening years.23

Lineage and Legacy

A year later, on 26 February 1850, Tan died of an unknown disease. He was only 52. His fortune was rumoured to be a princely sum of 500,000 Spanish dollars, which was shared between his widow, three sons and three daughters.24

The 19 March 1850 edition of The Straits Times reported that “his remains were removed to the place of burial, with much pomp and pageantry, followed by a large concourse of mourners and spectators, including many of the European community, who enjoyed his friendship while alive and paid the last tribute of respect by following his remains to the place of interment”.25

There was no mention of where Tan was originally buried, but his grave was eventually moved to the current site on Outram Hill, a plot of land bought by his eldest son Tan Kim Ching (sometimes spelt Tan Kim Cheng). The latter followed in his father’s philanthropic footsteps and has a road named after him in Tiong Bahru.26

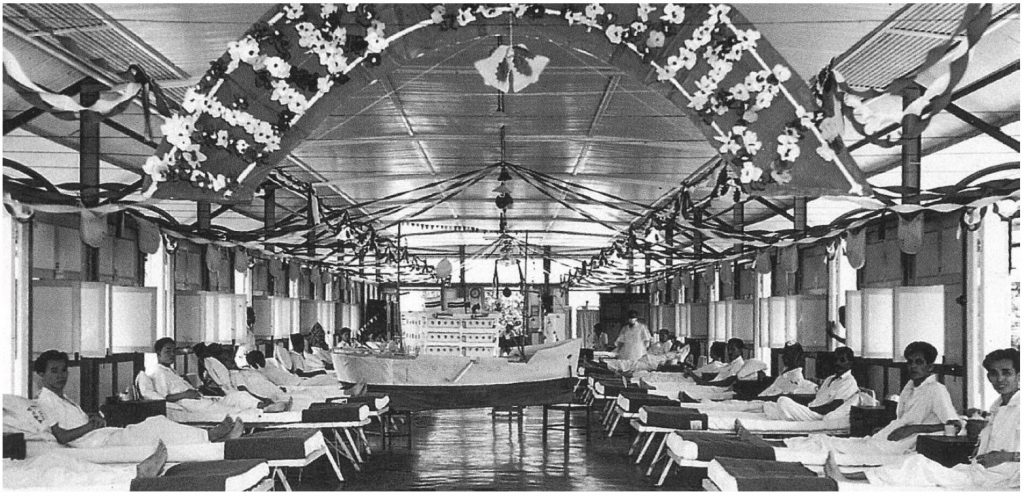

This younger Tan, who took over his father’s business and expanded it to include rice mills in Saigon (Ho Chi Minh City) and Siam (Thailand), was instrumental in expanding and moving “Tocksing’s Hospital” to Balestier Plain in 1860. The hospital, bearing his father’s name, eventually shifted to its current site on Moulmein Road in 1909.27

Apart from financing and building the hospital, Tan Tock Seng was also a founding leader of the Singapore Hokkien Huay Kuan clan association, which was set up in 1840 and still exists today. It provided assistance in securing accommodations, jobs and burial services for early Chinese immigrants to Singapore.28

Around the same time, Tan also contributed funds towards the building of Thian Hock Keng Temple at Telok Ayer Street. Singapore’s oldest Hokkien temple, the centre of worship for the Hokkien community, was gazetted as a national monument on 28 June 1973.29

Tan’s illustrious descendents, such as the aforementioned son Tan Kim Ching, grandson Tan Chay Yan (who also has a road named after him in Tiong Bahru) and great-grandsons Tan Boo Liat and Tan Hoon Siang, carried on his legacy as prominent merchants and philanthropists in the community.

Tan Kim Ching was made the first Siamese Consul in Singapore by King Mongkut in 1863, and later in 1885, King Chulalongkorn elevated his title to that of Consul-General. He was the Hokkien Huay Kuan’s first chairman and donated generously to improve health and education in Singapore.30 Tan Chay Yan, the first rubber planter in Malaya, also funded the constructions of schools and medical facilities.31

Tan Chay Yan’s son, Tan Hoon Siang, who took over his father’s business, contributed to charity as well as to botany by producing a new hybrid orchid.32 Hoon Siang’s cousin, Tan Boo Liat, a strong supporter of Chinese revolutionary leader Sun Yat Sen and president of the Singapore Kuomintang, initiated the setting up of the Singapore Chinese Girls’ School. Both Kim Ching and Boo Liat are buried at the Bukit Brown Cemetery.33

Beyond these few famous names, little else is known about Tan Tock Seng’s lineage. At a ceremony to launch the commemorative book of Tan Tock Seng Hospital’s 150th anniversary in 1994, some of his descendants were present.

Great-great-grandson John Tan (grandson of Tan Chay Yan), who runs several family companies, told The Straits Times: “The first thing people ask when they find out that you are a descendant of Tan Tock Seng is, ‘Oh, he must have left you billions of dollars, where is it?’”34

“That’s not true. Over the years, the descendants mismanaged and squandered the wealth, the war took its toll, and so by the time it came to our generation, we had to make it on our own.” Beyond what has been recorded publicly, “very little by way of documentation or material belongings has passed down the family,” he added.

In May 2016, news of the sale of a bungalow at 9 Cuscaden Road, home of the late Tan Hoon Siang, made the headlines – an indication perhaps that not all the wealth had been fritttered away. The house and its 25,741 sq-ft plot of land was sold for a whopping $145 million in May – one of the highest ever paid for a private property in Singapore.35

Great-grandson Tan Hoon Siang, who headed several rubber companies in Malaysia, was also a chairman and director of Bukit Sembawang Estates until his death in May 1991. He was a keen botanist, and a misthouse at the Singapore Botanic Gardens was named after him.36

With this sale – the house will be demolished and the land zoned for hotel redevelopment – commercialisation seems to have swallowed the humanitarian spirit of Tan Tock Seng. The only visible sign of his altruism is the hospital bearing his name.

Like many other philathropists of his time, Tan and his peers gave generously to causes that would benefit society through education and healthcare. But unlike other pioneers who had roads named after them, Tan was special in that he was the only one to leave behind a hospital named after him – ensuring that his legacy will be remembered not only by his descendants but also by future generations of Singaporeans.

Unfortunately, it is a heritage that is becoming increasingly brittle. Given Singapore’s penchant for acronyms – most people know Tan Tock Seng Hospital today as TTSH − one fears that future generations could become even less familiar with the forgotten pioneer and his legacy to Singapore’s history.

Sue-Ann Chia is a journalist with over 15 years experience covering politics and current affairs at various newspapers, including The Straits Times and Today. She is currently the Associate Director at the Asia Journalism Fellowship and a Director at The Nutgraf, a boutique writing and media consultancy.

Sue-Ann Chia is a journalist with over 15 years experience covering politics and current affairs at various newspapers, including The Straits Times and Today. She is currently the Associate Director at the Asia Journalism Fellowship and a Director at The Nutgraf, a boutique writing and media consultancy.Notes

-

Quek, F. (1989, January 28). Photo display to honour Singapore pioneers. The Straits Times, p.15. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Graves of Tan Tock Seng, Chua Seah Neo & Wuing Neo. (2013). Our Heritage: Tiong Bahru, (pp.18–19). Retrieved from National Heritage Board website. ↩

-

Sivanathan, N. (2013, September/October). Lessons of a forefather. Lifewise, (47), p. 23. Retrieved from National Healthcare Group website. ↩

-

National Library Board. (2008). Tan Tock Seng written by Tien, Jenny. Retrieved from Singapore Infopedia; Sivanathan, Sep/Oct 2013, p. 23. ↩

-

National Library Board, 2008; Dhoraisingham, K.D., & Samuel, D.S. (2003). Tan Tock Seng: Pioneer: His life, times, contributions and legacy (p. 9). Kota Kinabalu: Natural History Publications (Borneo). Call no.: RSING 338.04092 KAM ↩

-

Turnbull, C.M. (1989). A history of Singapore, 1819–1988 (2nd ed) (p. 14). Singapore: Oxford University Press. Call no.: RSING 959.57 TUR-[HIS] ↩

-

Dhoraisingham & Samuel, 2003, p. 4. ↩

-

The Singapore Free Press. (1850, March 1). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser (1835–1869), p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

National Library Board, 2008; When lepers roamed the streets. (1956, May 5). The Straits Times, p. 9. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

National Library Board, 2008; Dhoraisingham & Samuel, 2003, p. 23. ↩

-

Dhoraisingham & Samuel, 2003, p. 23. ↩

-

National Library Board, 2008; Tan Tock Seng and the war on diseases. (1974, September 26). New Nation, p. 7. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser (1835–1869) , 1 Mar 1850, p. 1. ↩

-

New Nation , 26 Sep 1974, p. 7; Straits Times special feature: Towkay forced hand of govt. to build hospital. (1961, December 7). The Straits Times, p. 9. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

New Nation , 26 Sep 1974, p. 7 ↩

-

The Straits Times, 7 Dec 1961, p. 9. ↩

-

The Straits Times, 7 Dec 1961, p. 9; Buckley, C.B. (1902). An anecdotal history of old times in Singapore (Vol. II) (p. 408). Singapore: Fraser & Neave. Call no.: RRARE 959.57 BUC ↩

-

New Nation , 26 Sep 1974, p. 7 ↩

-

In 1830, the Straits Settlements – comprising Singapore, Malacca and Penang – was made a residency of the Presidency of Bengal under the governor-general of India based in Calcutta, India. ↩

-

New Nation , 26 Sep 1974, p. 7 ↩

-

New Nation , 26 Sep 1974, p. 7 ↩

-

The Straits Times, 5 May 1956, p. 9; Song, O, S. (1923). One hundred years’ history of the Chinese in Singapore (pp. 62–63). London: John Murray. Call no.: RCLOS 959.57 SON ↩

-

The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser (1835–1869), 1 Mar 1850, p. 1. ↩

-

Untited. (1850, March 19). The Straits Times, p. 4. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Dhoraisingham & Samuel, 2003, pp. 52,79. ↩

-

Dhoraisingham & Samuel, 2003, pp. 55–59. ↩

-

Singapore Hokkien Huay Kuan. (2015). History. Retrieved from Singapore Hokkien Huay Kuan website. ↩

-

National Library Board. (2010). Thian Hock Keng written by Tan, Bonny. Retrieved from Singapore Infopedia. ↩

-

Tiong Bahru Estate. (2007. August 28). Tan Kim Ching. Retrieved from Tiong Bahru Estate Blog. ↩

-

Cheong, K. (2014, July 28). Tan Tock Seng’s descendants celebrate Tiong Bahru link. The Straits Times, p. B3. Retrieved from Tan Tock Seng Hospital website. ↩

-

Dhoraisingham & Samuel, 2003, p. 91; The Orchid Society of Southeast Asia. (2014). Our history. Retrieved from The Orchid Society of Southeast Asia website. ↩

-

Ee, J.W.W. (2009, August 2). Tan Tock Seng clan’s grave undertaking. The Straits Times, p. 14. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Loh, S. (1994, September 4). Following in the footsteps of a giant. The Straits Times. p. 9. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Whang, R. (2016, May 24). HK tycoon buys Cuscaden bungalow for $145m. The Straits Times, p. 3. Retrieved from Factiva via NLB’s eResources website. ↩

-

Koh, J., & Whang, R. (2016, April 5). House of Tan Tock Seng’s kin could fetch $170m. The Straits Times, p. 4. Retrieved from Factiva via NLB’s eResources website. ↩