Script & Stage: Theatre in Singapore from the 50s to 80s

A new exhibition on Singapore theatre traces its growth from its nascent days in the 1950s when traditional art forms were dominant, as Georgina Wong explains.

The “Script & Stage: Theatre in Singapore from the 50s to 80s” exhibition held at the National Library Building in 2017.

The “Script & Stage: Theatre in Singapore from the 50s to 80s” exhibition held at the National Library Building in 2017.

Although theatre in Singapore has a relatively short history of some 60 years, with its foundations having been laid only in the 1950s, it is made complicated by the fact that the various communities who engaged with theatre in the early days did so independently of one another.

Thus, the Chinese, Malay, Tamil and English theatre scenes developed in parallel, relatively isolated within each community, and rarely crossed boundaries until the 1980s when multilingual and multidisciplinary productions were staged. Therefore, any attempt to study and understand Singaporean theatre as a unified whole is extremely challenging, and likely explains the dearth of research and documentation on the subject.

“Script & Stage: Theatre in Singapore from the 50s to 80s” – which takes place on levels 7 and 8 of the National Library Building until 26 March 2017 − tracks the development of this art form over four decades, from its inception and formative years in the turbulent post-war period of the 1950s and 60s to its growth and maturity in the 1970s and 80s. All this would lead to a flourishing theatre scene in the 1990s and beyond.

The exhibition is by no means exhaustive, but seeks to give a general overview of the development of theatre in relation to the social and political history of Singapore through the performing arts collection of the National Library. Here are some pivotal moments in our theatre scene over the four significant decades.

The Turbulent 50s

Pre-war theatre in Singapore was generally restricted to traditional art forms such as Chinese wayang (street opera) orbangsawan (Malay opera). While there was a revival of theatre activity after the Japanese Occupation until the 1950s, local playwriting was still very much in its infancy. Although there was a lack of good quality scripts from Malayan playwrights, this did not stop theatre groups from experimenting and regularly staging plays.

For post-war theatre practitioners, the performance stage provided a platform to portray social realities and the clash of cultures. Theatre was also regarded as an agent for change and action within the Chinese community in the 1950s. Theatre activity in schools was often politically charged, and reflected the socio-political issues and sentiments of the day.

This was a time when the Chinese community viewed the British colonial government as being biased against the Chinese-educated. Policies such as the National Service Ordinance (1954), the white paper on bilingual education in Chinese-medium schools (1953) and the deregistration of the Singapore Chinese Middle Schools Students’ Union (1956) were viewed by the Chinese as infringements on their autonomy and culture – and would result in violent street protests and riots.

The Burgeoning 60s

Up until the 1960s, English-language theatre in Singapore had been the preserve of the expatriate European community, staged by amateur groups such as The Stage Club and The Scene Shifters. What little local English playwriting that existed took place mainly in schools and universities.

The theatre scene changed with the emergence of local playwrights such as Lim Chor Pee (1936–2006) and Goh Poh Seng (1936–2010). Driven by a passion for literature and theatre, as well as a desire to see Malayan realities depicted on stage, they went on to establish the first two local amateur English-language theatre clubs in Singapore – ETC by Lim and Centre ‘65 by Goh. Both Lim, a lawyer by profession, and Goh, a doctor, shared similar backgrounds, having received their higher education in the UK.

Their works are considered as important milestones in Singaporean English literature and planted the seeds for a local English-language theatre scene – even as playwrights struggled to find a “Singaporean voice” on stage. Lim’s breakthrough Mimi Fan (1962), for instance, is now considered Singapore’s first English language play.

The mid-1960s is often referred to as the “Golden Age” of Tamil theatre in Singapore because of the proliferation of quality local scripts and the large number of troupes staging Tamil language plays.

However, the Tamil theatre scene was not without its problems. A small Tamil population in Singapore meant that audiences were limited and theatre troupes struggled to stay afloat. In spite of this, Tamil theatre continued to grow and expand into other forms of media such as the radio.

The Experimental 70s

Within the Malay community for instance, a new generation of dramatists emerged in the 1970s and began pushing the boundaries of Malay theatrical art forms. These playwrights were looking to create a new form of theatre that would shape a unique identity for contemporary Malay drama that was independent of Western influence. One innovative result was the incorporation of traditional Malay art forms, such as silat (Malay martial arts) into contemporary plays.

In general, the theatre scene in the 1970s struggled on several fronts. English theatre, in particular, was badly hit by the withdrawal of British troops from Singapore. The expatriate community had made up the majority of theatre practitioners and audiences since World War II.

Tamil theatre struggled with small audiences and talent pools from which to draw. Several Tamil drama groups, including the Rational Drama Troupe, were forced to shut down in the late 1960s due to financial difficulties.

The Chinese theatre scene flourished for a while in the early 1970s. According to Kuo Jian Hong, artistic director of The Theatre Practice, theatre venues would be packed with people watching plays that were often left-leaning. In 1976, however, there was a crackdown on leftist elements in the community and several key theatre practitioners were detained. This put a huge dampener on Chinese theatre for the rest of the decade, although a few groups continued to perform regularly.

The Flourishing 80s

The 1980s was something of a game-changer for local theatre, seeing several leaps in innovation and quality in both script writing as well as theatre production.

Practitioners and playwrights such as Kuo Pao Kun, Stella Kon, Ong Keng Seng and Michael Chiang began writing and producing works that could stand up to foreign productions in terms of quality and critical reception with Singapore audiences and critics.

High-quality scripts and productions such as Kuo Pao Kun’s groundbreaking The Coffin is Too Big for the Hole (1985) and the multilingual Mama Looking For Her Cat (1988), and Stella Kon’s monodrama, Emily of Emerald Hill (1984) resulted in several amateur theatre groups turning professional – like Practice Theatre Ensemble (now known as The Theatre Practice), TheatreWorks and the Necessary Stage.

By the early 1990s, the local theatre scene had come into its own, paving the way for new amateur theatre groups to emerge and contribute to the vibrant performing arts scene we see today in Singapore.

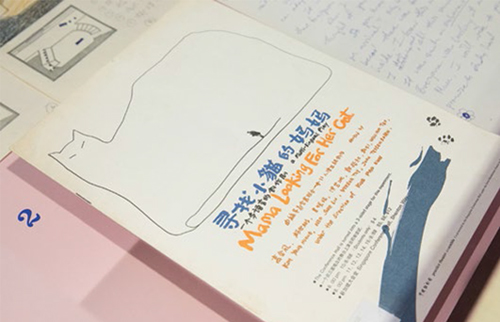

Programme booklet and handwritten draft of Mama Looking For Her Cat by Kuo Pao Kun.

Programme booklet and handwritten draft of Mama Looking For Her Cat by Kuo Pao Kun.

Guests at the launch of “Script & Stage: Theatre in Singapore from the 50s to 80s” on 27 October 2016.

Guests at the launch of “Script & Stage: Theatre in Singapore from the 50s to 80s” on 27 October 2016.

The 50s

家, Jia (Family). Adapted by 曹禺 (Cao Yu, 1910–1996) from the novel by 巴金 (Ba Jin, 1904–2005 ). Presented by the Chung Cheng High School Drama Club, 1954

In 1954, Jia was staged at the Victoria Theatre for 16 days to full houses, a milestone in Malayan theatre. Over 200 people were involved in the production, with each performance held over two nights and lasting more than six hours. Tickets were sold out within three days – a remarkable feat considering it was not a fundraising production.

The play was written in 1931 by the well-known Chinese writer Ba Jin, who based it on his childhood years in Sichuan province, China. Jia exposes the dark, repressive side of a feudal Chinese family through the lives of three brothers. The play highlights the oppressiveness of the old social system in China, and how a young generation tries to break free from it.

The 60s

The Elder Brother. Goh Poh Seng (1936–2010). Produced by The Lotus Club, University of Singapore, 1966

The staging of The Elder Brother is cited as the first time Singlish was used on a public stage. Goh, who wrote the play in 1966, was a novice playwright at the time, experimenting with different forms of the English language to find a fit that would properly represent English as it was used and spoken in Singapore. The characters in the play use a mix of English and Singlish on stage.

அடுக்கு வீட்டு அண்ணாசாமி, Adukku Veetu Annasamy (Annasamy: A Flat Dweller). புதுமை தா சன் Puthumaithasan (P. Krishnan, 1932–). Broadcast on Radio Singapura from 1969–70.

Adukku Veetu Annasamy is a radio drama series written by P. Krishnan (also known as Puthumaithasan) that was broadcast weekly from 1969 to 1970. Thanks to several repeat broadcasts between 1975 and 1985, the play captivated radio audiences for almost 20 years. It revolves around Annasamy, a man who observes and comments on the lives of the people living in his housing estate, with his wife Kokilavani. It is noteworthy for its depiction of the everyday lives of Singaporeans.

The 70s

Matahari Malam (The Night’s Sun). Masuri S.N. (Masuri bin Salikun, 1927–2005). Staged by Persatuan Kemuning Singapura, 1978.

Written as a collaborative effort between the drama group Persatuan Kemuning and the literary association Angkatan Sasterawan ’50 (or ASAS ’50), the partnership saw ASAS ’50 providing quality scripts and Persatuan Kemuning staging the plays. This was not uncommon in the Malay literary scene, where writers often crossed over into drama and vice versa. One of the founders of ASAS ’50 was the Singaporean Malay literary pioneer Masuri S.N. Better known as a poet, Matahari Malam was one of the few plays Masuri wrote in his lifetime, along with Dari Curfew. Regarded as a bold experimental work, Matahari is about an author who is confronted by five fictional characters of his own creation, who express displeasure at how their characters and storylines are being written.

寻找小猫的妈妈, Xunzhao xiaomao de mama (Mama Looking For Her Cat). Directed by Kuo Pao Kun (1939–2002). Staged by the Practice Theatre Ensemble, 1988.

Till today, Kuo’s iconic work, which he wrote in 1988, is considered as one of the most influential productions in Singapore’s theatre history. The production was performed by a multiracial ensemble who used four languages and three Chinese dialects on stage: English, Malay, Mandarin, Tamil, Hokkien, Cantonese and Teochew. The actors also employed non-verbal expressions such as body movements and gestures to explore the widening language divide in Singapore.

The play examines the consequences of language policies in Singapore, resulting in Mama, who speaks only Hokkien, becoming estranged from her English-speaking son.

The 80s

Emily of Emerald Hill. Stella Kon (1944–). Directed by Max Le Blond,1985. This was a breakthrough for English-language theatre in Singapore when it was staged in 1985 with Margaret Chan in the lead role. Written in 1982 while Kon was living in Edinburgh, UK, the play has been produced well over 50 times in Singapore, Malaysia and around the world. The monodrama is influenced by Kon’s Peranakan (Straits Chinese) heritage, and draws inspiration from her childhood home on Emerald Hill and the life of her maternal grandmother.

All the scenes in Emily are performed by a single actress, who mimes and interacts with unseen characters on and off stage. Its simplicity was considered avant-garde for its time, but what was most innovative was the play’s use of language. Emily’s ability to switch seamlessly from Singlish and a mix of Malay and Hokkien to proper English with a clipped British accent held audiences in thrall. It also set the standard for an authentic Singaporean voice to be expressed on stage in the following decades.

“Script & Stage: Theatre in Singapore from the 50s to 80s” is held on levels 7 and 8 of the National Library Building until 26 March 2017. A series of programmes has been organised in conjunction with the exhibition, including public talks by playwrights, directors and artistes; guided tours by curators; and school tours. For more information, look up the website: www.nlb.gov.sg/exhibitions/

Georgina Wong is an Assistant Curator with Exhibitions & Curation at the National Library, Singapore. She is the lead curator of "Script & Stage: Theatre in Singapore from the 50s to 80s".

Georgina Wong is an Assistant Curator with Exhibitions & Curation at the National Library, Singapore. She is the lead curator of "Script & Stage: Theatre in Singapore from the 50s to 80s".

REFERENCES

柯思仁 [Ke, S.R.]. (2013).《戏聚百年: 新加坡华文戏剧 1913–2013》[Scenes: A hundred years of Singapore Chinese language theatre 1913–2013]. 戏剧盒: 新加坡国家博物馆. Call no.: Chinese RSING 792.095957 QSR

周宁. (主编) [Zhou, N. (Ed.)]. (2007).《东南亚华语戏剧史》[History of the Chinese theatre in Southeast Asia]. Xiamen: 厦门 大学出版社. Call no.: Chinese RSING 792.0959 HIS

Don, R., et al. (Eds.). (2001). The world encyclopedia of contemporary theatre: Asia/Pacific. London: Taylor & Francis. Retrieved from Googlebooks website.

Krishnan, S. (Ed.). 9 lives: 10 years of Singapore theatre 1987–1997: Essays. Singapore: The Stage. Call no.: RSING 792.095957 NIN

Mohamad Nazri Ahmad. (2000). Seni Persembahan Drama Melayu Moden. Bangi: Penerbit Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia. Call no.: Malay R 899.282 MOH

Oon, C. (2001). Theatre life: A history of English-language theatre in Singapore through The Straits Times (1958–2000). Singapore: Singapore Press Holdings. Call no.: RSING 792.095957 OON

Sikana, M., & A. Raman Hanafiah. (2008). Sejarah kesusasteraan Melayu moden: Drama. Kuala Lumpur: Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka. Call no.: Malay R 899.28209 ABD

Sarma, S.S. [எஸ். எஸ். சர்மா]. (2004). நாடகம் நடத்தினோம் [Nāţakam naţattinōm]. சிங்கப்பூர்: எஸ். எஸ். சர்மா [Cinkappūr: Es. Es. Carmā]. Call no.: Tamil RSING 894.8112 SAR

Varathan, S., & Sagul Hamid. (2008). Development of Tamil drama in Singapore. Singapore: Singapore Indian Artistes Association. Call no.: RSING 792.095957 VAR-[SRN]