A Lifetime of Labour: Cantonese Amahs in Singapore

The black-and-white amah, renowned for her domestic skills, has left a mark on history in more ways than one, as Janice Loo tells us.

An amah with her mistress and charge at the Singapore Swimming Club in 1942. Photo by Gavin G. Wallace. PAColl-2480. Alexandar Turnbill Library, Wellington.

An amah with her mistress and charge at the Singapore Swimming Club in 1942. Photo by Gavin G. Wallace. PAColl-2480. Alexandar Turnbill Library, Wellington.Hair coiled up in an elegant bun or worn in a single plait down the back, a white blouse paired with ankle-length black trousers, and black slippers – this was the quintessential look of the amah, or Chinese female domestic servant, from bygone days.1

Apart from their iconic black-and-white samfu attire, amahs have earned a place in popular memory for their strong work ethic and steadfast loyalty. Many were former silk production workers from the Pearl River Delta of Guangdong province in China.2 The majority never married and were part of an anti-marriage tradition unique to the silk-producing areas of the region, particularly the district of Shunde, where the phenomenon originated.3

An amah in her black-and-white samfu attire cooking on a gas stove, 1950. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

An amah in her black-and-white samfu attire cooking on a gas stove, 1950. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.Seeking a better life, these women came to this part of the world in the 1930s to work in the homes of wealthy families, eventually dominating the field of paid domestic service well into the 1960s and 70s.4 At a time when women in Chinese society were bound by traditional Confucian values to be “dutiful wives and virtuous mothers” (贤妻良母, xian qi liang mu), Cantonese amahs broke the mould by carving an independent livelihood away from home and determining their own destiny.

A scene depicting silk production in 17th-century China. By the early 1900s, the Pearl River Delta had become a major production centre for silk. Photo by Peter Horree/Alamy Stock Photo.

A scene depicting silk production in 17th-century China. By the early 1900s, the Pearl River Delta had become a major production centre for silk. Photo by Peter Horree/Alamy Stock Photo.Daughters of the Delta

Compared with other parts of China where the birth of a girl would be greeted with dismay – female infanticide was tragically common then – women in the Pearl River Delta were valued by their families for their ability to contribute to the household income.5 In the early 1900s, the Pearl River Delta was a major centre for silk production, especially in Shunde. By 1925, about 70 percent of the land there and 80 percent of its population were devoted to the cultivation of silkworms (or sericulture).6 Women made up a substantial proportion of the labour force engaged in the silk cottage industry.7

The Pearl River Delta region was also conducive for a form of agriculture that combined fish breeding with mulberry cultivation. Mulberry trees were important because their leaves were fed to the silkworm larvae, whose excrement in turn became food for the fishes. The region’s balmy tropical climate spurred the rapid growth of mulberry trees such that up to seven broods of silkworms could be produced annually, surpassing the norm of two broods a year in other silk-producing areas of China.8

There was a division of labour between the sexes across the different stages of silk production. Men handled the heavier aspects of farm work which, along with fish rearing, included the transport and marketing of mulberry leaves, silkworm eggs and cocoons. Women harvested the mulberry leaves, raised silkworms, and produced silk threads by soaking the cocoons in hot water to loosen the fibres before reeling or spinning them into strands.9 In some locales, men also helped to weave the silk threads into cloth; such work was an important source of income for many families.10

Typically, there were more unmarried women engaged in the silk cottage industry than married ones. With their heavy domestic responsibilities, married women were less likely to participate in sericulture, particularly the stage where silkworm eggs were hatching and turning into larvae, because of the taboo associated with notions about the impurity of the female body during pregnancy and childbirth. In Shunde, married women were also excluded from the thread-loosening process as the constant association with water was believed to affect fertility. Therefore, unmarried women had a higher economic value to their families, and some parents found it more worthwhile to keep a daughter at home for as long as she wished than to marry her off and forgo a key source of income.11

Industrialisation changed the face of silk production and strengthened the impetus for women to remain single. Filatures, or factories where silk is reeled, were set up and these employed an all-female workforce as women were found to be more careful when handling silkworm cocoons and processing them into silk threads. Younger women were also preferred for their smooth hands, nimble fingers and good eyesight that made for skilful work. On top of these physical traits, single or married but childless women were favoured as they were perceived to be less encumbered by family commitments that could interfere with their ability to work.12

As more women migrated to the towns to work in industrial establishments, sericulture in the villages declined as a result of the dwindling labour pool. Mechanisation also obviated the need for male labour in silk production and, with fewer jobs available at home, large numbers of men began to seek employment outside of China, in places such as Singapore, Malaya and Hong Kong. As a result of this exodus, women became the main providers for their families and wielded greater influence over domestic affairs than ever before.13

In her study of marriage resistance in rural Guangdong, anthropologist Marjorie Topley identified the local economic system as a key factor behind the growth of the anti-marriage practice because it gave single women the means to support themselves through paid work outside of the home. With economic self-sufficiency, these women began to question marriage and childbearing as their accepted fate.14

An Independent Streak

Writing in the 1930s, American journalist Agnes Smedley observed that “thousands of peasant homes depend for a large part of their livelihood upon the modest earnings of a wife or daughter and this important productive role played by women has struck a serious blow at the old idea of the inferiority of women”. She further noted that the silk workers, conscious of their own worth, carried themselves with a “dignified and independent air”.15 Yet, this outlook did not stem from changes in the local economic climate alone, but was rooted in long-standing socio-cultural practices that shaped the women’s resistance towards marriage.

One unique feature of the Pearl River Delta region was the establishment of “girls’ houses” (女仔屋, nü zai wu) in villages. These functioned as a place for adolescent girls from the same village to gather, socialise and learn from one another. They worked during the day and would meet at the girls’ house in the evenings to chat, tell stories, play games and sing ballads. It was common to see girls spending their nights at the house, partly to escape the cramped living conditions and lack of privacy in their own homes. These houses facilitated the informal education and interaction of the girls: older girls would instruct the younger ones in sewing, embroidery, reading, writing, social etiquette as well as religious rites and customs. Girls from the same house formed strong bonds from the experience and would pledge to treat each other like “sisters” (姐妹, jie mei).16

The girls’ house also played an instrumental role in the shaping of attitudes against marriage among the women of the Pearl River Delta. Married life, particularly its trials and tribulations, was a topic of discussion among the girls when they reached marriageable age. From having to obey one’s husband and in-laws to the obligatory duty of producing many offspring, especially sons, it was no surprise that many young women came to fear and resent the prospect of being a wife and mother. Marriage and motherhood meant a severe curtailment of their freedom and independence. The improved economic position of unmarried women further strengthened such sentiments, giving rise to unique marriage-resistance practices, of which sworn spinsterhood was one.17

In fact there was a special rite that initiated one into spinsterhood. A woman became a sworn spinster through an elaborate ceremony comprising a hairdressing ritual, a vow of celibacy, and worship of domestic gods and ancestors. A sworn spinster then became known as “a woman who combed her own hair up” (自梳女, zi shu nü), in reference to the hairdressing ritual sor hei (梳起, shu qi; which literally means “comb up”) during which her hair would be combed into a bun at the back of her head to symbolise the attainment of social maturity. This ritual was akin to the one traditionally performed to mark a girl’s transition into adulthood upon marriage. Similar to a wedding, the ceremony was an occasion to be celebrated and would be held on an auspicious day and conclude with a banquet for family, friends and fellow “sisters”.18

A close-up of a bun that is secured with a hairnet and pin. Kouo Shang-Wei Collection (郭尚 慰收集). Family of Kouo Shang-Wei and National Library Board, Singapore.

A close-up of a bun that is secured with a hairnet and pin. Kouo Shang-Wei Collection (郭尚 慰收集). Family of Kouo Shang-Wei and National Library Board, Singapore.A sworn spinster was treated like a married daughter and could no longer live with her family or count on parental support. She was forbidden from returning to her village even in old age because of the belief that her death at home would bring misfortune to the family. Spinsters who moved to larger villages and towns for employment typically shared a rented room with other “sisters”. When they grew too old to work, those with the financial means would pay to take up residence in an established “spinsters’ house” (姑婆 屋, gu po wu) – the equivalent of a girls’ house for older, unmarried females – or combine resources with their “sisters” to buy or build one. Another option was retirement in a “vegetarian hall” (斋堂, zhai tang), which was by and large similar to a spinsters’ house except for the observance of a vegetarian diet and heavier emphasis on religious activities.19

Assuming the status of a sworn spinster represented the ultimate strategy by a woman to remain single and pursue an independent life that was socially acceptable and even admired in this part of China. Her decision to remain chaste, to emigrate for employment and to remit part of her wages home to support her family was seen as an honourable sacrifice.20

Becoming an Amah

The decline of the silk industry in the 1930s prompted thousands of Cantonese women to leave the Pearl River Delta in search of employment away from home. Meanwhile, as a result of the Great Depression, immigration restrictions were enforced to control the supply of Chinese male labour in Singapore and Malaya. The Aliens Ordinance 1933 enabled the government to adjust the monthly quota of Chinese male immigrants as and when necessary according to the political, social and economic needs of the colony. The immediate effect of the quota – initially set at 1,000 monthly – was to drive up the cost of passage for Chinese males due to stiff competition for limited tickets.21

Since the quota did not apply to Chinese females, shiploads of Cantonese women came to work and support their families in place of their menfolk. Enterprising ticket brokers at the ports in China would sell a ticket for a male passenger only if three to four tickets for female passengers were purchased along with it. As a result, this led to a net increase of over 190,000 Chinese female immigrants to Singapore and Malaya between 1934 and 1938.22 This state of affairs continued until May 1938, when a monthly quota of 500 was imposed on women.

There was a wider range of employment opportunities available in Malaya for these women, who found work in agriculture, tin mining and rubbertapping, especially in the states of Perak and Selangor. However, in urban areas like Singapore and other parts of Malaya such as Penang, Ipoh and Kuala Lumpur, the majority worked as domestic servants for affluent Chinese and European households.23 Domestic service was a popular and practical choice as employment was easy to find and the work was seen as respectable and neither too difficult nor unfamiliar.24 Prior to the 1930s, paid domestic work was mainly carried out by Hainanese men called houseboys. These men were displaced by the arrival of the amah, whose subsequent domination of the industry effectively cemented the association between domestic service and women’s work.25

The pattern of social affiliation and mutual assistance organised along the lines of sisterhood and territorial origins in China was replicated in Singapore and Malaya. Amahs from the same village or district banded to form associations known as kongsi (公司). They pooled their wages to rent accommodations, known as kongsi fong (公司房), which ranged in size from a cubicle to a shophouse with a number of rooms, and in membership from two to as many as 50 women. Some kongsi fong functioned as a place for sleeping and storage of personal belongings, while others were elaborate clubhouses with benefit schemes and social activities for members. A well-organised kongsi fong also served as a recruitment agency and trade guild that helped to connect members with prospective employers as well as to help them negotiate for better employment terms.26

An amah entering a kongsi fong, 1962. Amahs pooled their wages to rent accommodations, known as kongsi fong (公司房), which ranged in size from a cubicle to a shophouse with a number of rooms. Kongsi fong were typically located in tenement blocks in Chinatown. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

An amah entering a kongsi fong, 1962. Amahs pooled their wages to rent accommodations, known as kongsi fong (公司房), which ranged in size from a cubicle to a shophouse with a number of rooms. Kongsi fong were typically located in tenement blocks in Chinatown. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.A woman intending to emigrate would usually engage the services of a sui haak (水客, shui ke; literally “water guest”), a middleman from the same district or village who, for an agreed fee, would make the necessary travel arrangements and provide advice on all matters relating to immigration and employment in the foreign land.27

Upon arrival at her destination, the newcomer would put up in the home of a friend or relative, or pay a small fee to lodge at a kongsi fong until she found work – most likely through recommendation by a fellow amah. At the same time, it was not unusual for employers needing a servant to enquire directly at the kongsi fong, where a list of the jobs available would be displayed on a board. If several women were keen on the same position, the unwritten rule was to give priority to the one who had been unemployed the longest to be interviewed first.28

A Lifetime of Labour and Love

Many amahs started out working for less affluent households as an “all-purpose servant”, or yat keok tek (in Cantonese, literally “one-leg-kick”), who managed all domestic tasks single-handedly. More well-to-do families could afford to hire a servant for each area of domestic activity – cooking, cleaning, childcare and general housekeeping – which was usually the case in European households. Working for an expatriate family had its perks in terms of higher wages, better accommodations, well-defined hours and a fixed job scope.29

Those working for European employers could expect to earn about twice as much compared with their counterparts employed by local families. However, amahs working in European households were expected to take care of their own meals and pay for this expense from their own purses. Another drawback was having to deal with a foreign culture and unfamiliar lifestyle. Tang Ah Thye, a former amah said, “I didn’t like the idea of working for Europeans. You’d have to bring your pots and pans to do your own cooking. Also rice, oil, etc. It’s like a major move. Also, I didn’t understand their language. I just didn’t like working for them in spite of higher salaries.”30

The most pressing concerns for an amah starting a new job were the pay, nature of work, size of the family, type of dwelling and their accommodations. As she gained experience and became familiar with the work, the ability to get along with her employer and family became more important since the work itself was more or less the same everywhere.31

Although the average employment term for an amah was 10 years, there were some who grew close to the families they served and worked for them until retirement, at around 60 years of age.32 Families were, likewise, fond of their amahs too. When expatriate housewife Marjorie Monks was interviewed by The Straits Times in 1957, she had this to say about her amah: “She has a loving loyalty. The children love her and you have only to say that Ah Loke is returning to Singapore to bring streams of tears into the house.” Four years earlier, the Monks and their three children had returned to England, taking Ah Loke with them. When Ah Loke was later offered a six-month paid leave while working in England, she put it off, saying, “Maybe next year if children no cry so much when I go.”33

An amah with her employer’s children, 1942. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

An amah with her employer’s children, 1942. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.Amahs who took care of children would dote on them like their own. Many of those who had been raised by amahs continue to regard them with great affection. Peranakan curator Peter Lee, for instance, recalls his amah Yip Ching Sim with fondness (see text box below).

When it came to their kin in China, amahs fulfilled their filial duties through remittances, letters and occasional visits. It was estimated that up to 70 percent of their wages was saved or remitted. Amahs were known for being frugal when it came to their own expenses but generous to their close friends and relatives, especially during special occasions.34 In a Straits Times report, Yip’s nephew recalled, “Life was very hard in China in the 1960s, but my aunt used to send back flour, peanuts, cooking oil, sugar and necessities. Without her, we probably would have starved.” Recounting her visits to China in 1963, 1985 and 1990, he added: “She came back with big straw baskets filled with cleavers, grinding stones, packets of beehoon, shoes and even bicycles. A bicycle was a big deal in those days.”35

Letter writers such as this man were once a common sight along “five-foot ways” in Chinatown. They provided an indispensable service in helping illiterate amahs communicate with their families back home. Kouo Shang-Wei Collection (郭尚慰 收集). Family of Kouo Shang-Wei and National Library Board, Singapore.

Letter writers such as this man were once a common sight along “five-foot ways” in Chinatown. They provided an indispensable service in helping illiterate amahs communicate with their families back home. Kouo Shang-Wei Collection (郭尚慰 收集). Family of Kouo Shang-Wei and National Library Board, Singapore.For the amah, preparation for retirement and the afterlife was of utmost importance. While some returned to China, as in the case of Ouyang Huanyan, who had worked for the late former Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew, others like the aforementioned Yip, retired in vegetarian halls or homes for the aged in Singapore. However, not all amahs were as fortunate because access to such options depended on whether they had squirrelled away enough savings for a comfortable retirement.36

End of an Era

Amahs have become a symbol of a bygone era, much like the Samsui women of yesteryear. In search of a better life, these former silk workers left their families and came to Singapore and Malaya in the 1930s. By the 1970s, amahs had become a vanishing breed as they retired from service or returned to China to live out their twilight years. At the same time, as a result of better education and economic development, young women in Singapore preferred jobs in the industrial and commercial sectors over live-in domestic work.

Today, foreign female domestic workers have taken on the role of modern-day amahs in many Singaporean households. Like the amahs of old, many domestic helpers labour from dawn till dusk – sometimes without a day-off – in order to provide a better life for their loved ones back home.

MY LIFE WITH AH SIM

Ah Sim, or Yip Ching Sim, was my amah. Every morning, at the break of dawn, she would slip quietly into the bedroom I shared with my brothers and rearrange our cotton blankets, making sure we were all properly covered. As silent as she tried to be, the jarring stream of light from the gap in between the door would wake me up, and through partially opened eyes, I would glimpse her approaching silhouette. I would shut my eyes tight and wait for that reassuring moment when I could feel the crumpled blanket being gently rearranged over my body.

I looked forward to that moment every day.

The first morning Ah Sim did not appear led to a wave of panic and a flood of tears, until another household helper, Siew Chan, a young Malaysian girl, told us that Ah Sim was merely feeling unwell. The next day the morning routine continued, much to my relief. Ah Sim must have been in her late 50s at that time, which to a child, seemed positively ancient. The reality is that Ah Sim lived to 106 years, passing away on 24 July 2017.

Canton to Singapore

Yip Ching Sim (叶静婵) was born in the Pun-yue (番禺, Panyu) district of Canton in 1911. Ah Sim’s parents were poor farmers, but she abhorred the farming life and when she was in her late teens, tagged along with her paternal aunt to Singapore to become an amah, a domestic servant.

Ah Sim always kept an old album of photos, and I remember her showing me an image taken when she arrived in Singapore in the late 1920s: her portly, middle-aged aunt dressed in black blouse and trousers, and next to her, attired in similar fashion, a gaunt and dishevelled young girl, looking uncertain and afraid. Photographs of the same girl taken in the 1930s and 1940s reveal a different person: a decidedly more confident woman, with hair neatly combed back into a long ponytail.

Ah Sim worked for several families before joining mine in 1958 as our cook. Just three years earlier, my father, Lee Kip Lee, a sixth-generation Peranakan working for the family business, had married my mother, a young nurse who was herself half-Peranakan and half-Cantonese. My parents had just moved into a new house in Bukit Timah, a gift from my paternal grandmother. At that time, we did not need a nanny. My eldest brother Dick who was barely two years old, was the only child then, and he was looked after by a grandaunt we all called Nenek (“grandmother” in Malay).

The rest of the children in the Lee household followed in quick succession and as it became increasingly difficult for my mother and Nenek to look after the brood, Ah Sim was asked to look after me and my younger brother Andrew. Not surprisingly, Dick’s first language – thanks to Nenek’s influence − was Baba Malay, while Andrew’s and mine was Cantonese. We spoke a multicultural melange of Baba Malay, Cantonese and English at home, and somehow we all understood each other.

Parenting in the 1960s was not like it is today, and in our family it can best be summed up as benign neglect. Everyone had their basic needs taken care of, and children were left to play and study together; as long as your school report card wasn’t a sea of red ink, you were considered a good child. My childhood was filled with fun and laughter, and the company of a motley rabble of siblings, cousins and the children of my parents’ friends. My parents created a liberal and loving domestic environment. But, it was Ah Sim who bathed, clothed and fed Andrew and me − and was there whenever she was needed.

Growing Up with Ah Sim

Ah Sim was an obsessively tidy person, and I was drawn to spending time with her in the servant’s quarters, observing her daily rituals with fascination. She would wash her hair in an enamel basin filled with what appeared to be preserved citrus fruit. Dressing her hair in a neat bun was another fastidious exercise: she would tie cotton tape around her head to hold the hair in place while tugging and combing her tresses before lacquering it with a special oil.

Ah Sim hand-sewed all her own clothes, including the knotted buttons she made for her blouses. On the first and 15th day of each lunar month she would prepare her own vegetarian meal, as was common among amahs as a form of religious devotion. The meal was spartan, comprising fried vegetables, a dish of roasted peanuts drizzled with thick soya sauce, and some boiled rice.

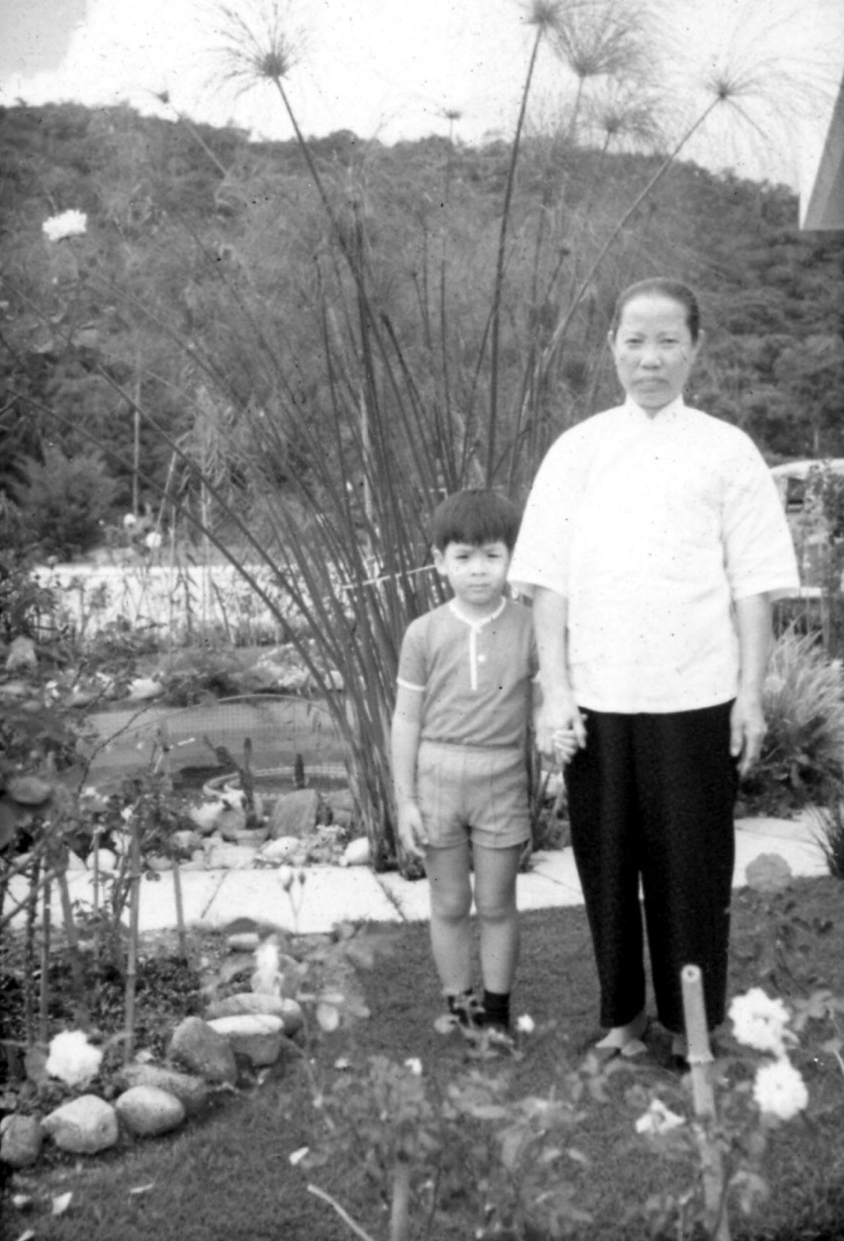

The author, Peter Lee, with his beloved Ah Sim. This photograph was taken while on holiday in Cameron Highlands, Malaysia, in 1969. Courtesy of Peter Lee.

The author, Peter Lee, with his beloved Ah Sim. This photograph was taken while on holiday in Cameron Highlands, Malaysia, in 1969. Courtesy of Peter Lee.

Thankfully, meals for us children was Cantonese comfort food. My mother referred to this as majie (see note 1) cooking, which included dishes such as chu yoke peng (猪肉饼, pork meatballs with onions in soya gravy), sam wong dan (三黄蛋, steamed egg custard with salted egg and century egg), and chow lup lup (炒粒粒, a stir-fried dish of diced fresh and salted vegetables, tofu and peanuts). At the heart of every meal was a hearty boiled soup made from pork, chicken or fish stock. We had a different soup every day.

Food on the table was a blessing for Ah Sim. I remember accompanying her to a fortune teller once. She had only one question, which expressed her singular concern: “Would I die from starvation?” (我会唔会饿死). The fortune teller laughed and allayed her fears, but years later I realised her anxiety harked to an era when famine, or being abandoned in old age, was a very real concern.

Ah Sim was the epitomy of graciousness with family and guests, insisting on observing the proper etiquette at home. How a girl from the countryside learnt the complex and refined subtleties of Cantonese civilities was always a wonder to me.

She addressed everyone by his or her rank, in the traditional manner. In the old days servants used specific terms when referring to each member of the family. For example my mother was Dai Siew Nai (大少奶, mistress of the house) and my father was Wawa (a Cantonese version of Baba). The family in turn addressed her simply as Ah Sim, or more politely as Sim Jie (sister Sim). Her social skills were impeccable; she not only knew the names of anyone who visited the house, but also whether they were in school, had graduated, or married.

But all decorum evaporated − and hell broke loose − not long after Ah Sim was asked to work with another amah in our home. In the kitchen, the two would engage in a shouting match where the crudest expletives would be hurled at each other. As it always transpired, the other amah would quit. Over time, to avoid this vexatious problem, my mother took to employing vapid young girls who presented no threat to Ah Sim.

Ah Sim only admitted to one vice in her youth: cigarettes. But she never smoked at home. As a devotee of Guanyin (Goddess of Mercy), she did not consume beef, which was the custom, and observed the practice of being vegetarian on new and full moon days.

Every month she would remit her salary back to her brother in Canton, and when he passed away, his children continued to benefit from her generosity. Her devotion to us was expressed with gifts, including a gold ring and a woollen scarf she knitted herself − but more importantly − unspoken love and loyalty.

In good old Chinese tradition, the ultimate expression of love was a thorough scolding. Ah Sim enjoyed the privilege − denied even to my mother − of berating me interminably while I just stood silent, barely croaking a whisper of protest. She never understood the rationale of the freelance work I did, and would not hesitate to remind me that I was good for nothing without a proper job, and useless for not getting married, and that she prayed endlessly to Guanyin in the vain hope that I would change my wicked ways.

Her Final Years

Chinese tradition considered it inauspicious for an amah to pass away in her employer’s house. Upon retirement she would typically return to China or live out her remaining years in an old folks’ home in Singapore. Ah Sim had heard a few horror stories about her sisters who went back. One ended her life by jumping into a fishpond.

The Tai Pei Old Folks’ Home off Balestier Road was regarded by amahs as the Ritz-Carlton of retirement homes. Ah Sim prayed hard to be admitted and vowed to become a full-time vegetarian (the home was run by Buddhist nuns) if her prayers were answered. Her wish was granted and in December 1990, at age 79, she entered the home and lived there for 27 years. It gave her enormous satisfaction that she had her sunset years in order. One day she even led me to the in-house columbarium, proudly pointing out the niche she had paid for with her own savings.

Ah Sim kept active in her twilight years, performing temple duties and learning to memorise Buddhist sutras. I would take her out to lunch and to the supermarket occasionally. These outings became less frequent as her health deteriorated.

The highlight of Ah Sim’s final years was her 100th birthday lunch in 2011, when I surprised her by inviting her relatives from Canton. Ah Sim burst into tears when she saw everyone, and expressed remorse that she could not honour her own mother in such a manner. It struck me that one could be a centenarian and still miss one’s own parent like an orphaned child.

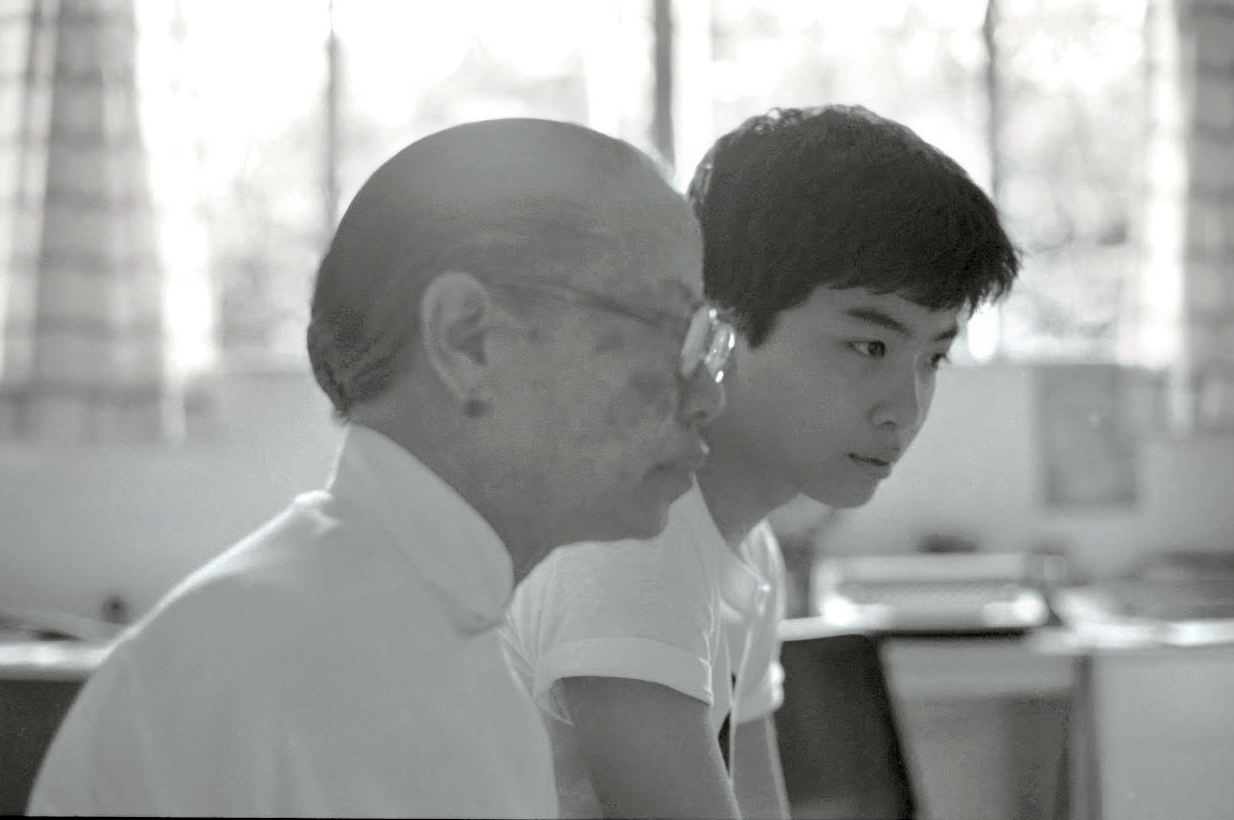

Peter Lee with Ah Sim at home in 1979. Ah Sim worked for the Lee family for 32 years before she retired in 1990. Courtesy of Peter Lee.

Peter Lee with Ah Sim at home in 1979. Ah Sim worked for the Lee family for 32 years before she retired in 1990. Courtesy of Peter Lee.

Ah Sim slipped away quietly in her final months; she was often asleep when I visited. It was funny how the roles were reversed. I was the one who was now rearranging her blanket. On the rare occasions I found her awake, she was always the consummate hostess, smiling and greeting everyone around her. Towards the end it would only take a few words from me to spark a response, words that she always uttered whenever we parted. She would break into a smile and repeat my words in a weak whisper: “Take care! Be careful!” (保重!小心!)

Peter Lee is an independent art and heritage consultant, and Honorary Curator of NUS Baba House. He is author of The Straits Chinese House and Sarong Kebaya: Peranakan Fashion in an Interconnected World 1500−1950, and has curated various exhibitions both in Singapore and overseas. Lee is currently working on a photography exhibition for the Peranakan Museum that opens in April 2018.

Janice Loo is a Librarian at the National Library, Singapore. Her responsibilities include collection management and content development as well as research and reference assistance on topics relating to Singapore and Southeast Asia.

Janice Loo is a Librarian at the National Library, Singapore. Her responsibilities include collection management and content development as well as research and reference assistance on topics relating to Singapore and Southeast Asia.

NOTES

-

There is another term, majie, which refers specifically to spinster amahs from Shunde district in Guangdong province. All majie worked as domestic servants or amahs, but not all amahs were majie. See Gaw, K. (1988). Superior servants: The legendary Cantonese amahs of the far east (pp. 89, 91, 105). Singapore: Oxford University Press. (Call no.: RSING 331.481640460951 GAW) ↩

-

Gaw, 1988, pp. 13, 39–40; Topley, 1988, pp. 25, 89; Topley, M. (1959, December). 333. Immigrant Chinese female servants and their hostels in Singapore. Man, 59, 213–215. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website. ↩

-

Gaw, 1988, pp. 43–44; Topley, M. (2011). Marriage resistance in rural Kwangtung (pp. 423–424). In M. Topley & J. DeBernardi. (Eds.), Cantonese society in Hong Kong and Singapore: Gender, religion, medicine and money (pp. 423–446). Singapore: NUS Press. (Call no.: RSING 305.895105125 TOP) ↩

-

Lai, A.E. (1986). Peasants, proletariats and prostitutes: A preliminary investigation into the work of Chinese women in colonial Malaya (p. 78). [Research notes and discussion paper no. 59]. Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. (Call no.: RSING 331.409595104 LAI) ↩

-

Howard, C.W., & Buswell, K.P. (1925). A survey of the silk industry of South China (p. 15). Hongkong: Commercial Press. Cited in Stockard, J.E. (1989). Daughters of the Canton Delta: Marriage patterns and economic strategies in South China, 1860–1930 (p. 138). Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press. (Call no.: R 306.810951 STO) ↩

-

Watson, R.S. (1994). Girls’ houses and working women: Expressive culture in the Pearl River Delta, 1900–41 (pp. 25–34). In M. Jaschok & S. Miers (Eds.), Women and Chinese patriarchy: Submission, servitude and escape (p. 33). Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press: London; Zed Books, Atlantic Highlands, N.J. (Call no.: RSING 305.420951 WOM) ↩

-

Topley, 2011, pp. 427, 436; Topley, M. (1954, May). Chinese women’s vegetarian houses in Singapore. Journal of the Malayan Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, 27 (1) (165), 51–67, p. 53. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website. ↩

-

Smedley, A. (2003). Chinese destinies (p. 159). Beijing, China: Foreign Languages Press. (Not available in NLB holdings) ↩

-

Topley, 2011, pp. 429–430; Stockard, 1989, pp. 34, 37–40, 194; Gaw, 1988, p. 41. ↩

-

Stockard, 1989, p. 70–73; Topley, 2011, p. 423, 440; Gaw, 1988, pp. 44–45. ↩

-

Gaw, 1988, pp. 41, 47; Stockard, 1989, p. 87; Topley, 2011, pp. 438, 440–441. ↩

-

Blythe, W.L. (1947, June). Historical sketch of Chinese labour in Malaya. Journal of the Malayan Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, 20 (1) (141), 64–114, p. 102. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website. ↩

-

Blythe, Jun 1947, p. 103 ↩

-

Topley, Dec 1959, p. 214; Ooi, K.G. (1992). Domestic servants par excellence: The black & white amahs of Malaya and Singapore with special reference to Penang. Journal of the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, 65 (2) (263), 69–84, p. 73. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website. ↩

-

Lai, 1986, p. 77; Lee, S.M. (1989, Summer). Female immigrants and labor in colonial Malaya: 1860–1947. The International Migration Review, 23 (2), 309–331, p. 323. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website. ↩

-

Topley, Dec 1959, p. 214; Lai, 1986, pp. 81–82; Ooi, 1992, p. 74. ↩

-

Gaw, 1988, p. 106; Lebra, J. (1980). Bazaar and service operations. In J. Lebra & J. Paulson, Chinese women in Southeast Asia (p. 72). Singapore: Times Books International. (Call no.: RSING 301.4120959 CHI) ↩

-

Mok-Ai, I. (1957, May 8). British housewives elect the Chinese amah queen of the nannies. The Straits Times, p. 16. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Wong, K.H. (2010, December 11). A long, loving life. The Straits Times, p. 8. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Toh, M., & Lim, R.Y. (2009, February 1). Majie recalls life with the Lees. The Straits Times, p. 6. Retrieved from NewspaperSG; Lai, 1986, p. 87. ↩