Going Shopping in the 60s

What was the act of shopping like for a generation that was more concerned about putting food on the table? Yu-Mei Balasingamchow ponders over our penchant for shopping.

Ask anyone who lived in 1960s Singapore where they used to shop in town, and they will invariably give one of two answers: Raffles Place, or High Street and North Bridge Road.

The shoppers from this generation, however, were vastly different from the throngs who congregate at Orchard Road or hang out in shopping malls today, many without the slightest intention of buying anything. Until 40 or 50 years ago, most Singaporeans did not have the disposable incomes nor the leisure time to “go shopping” whenever they liked. The oral history collections at the National Archives of Singapore contain numerous accounts of people mentioning Raffles Place or High Street as a shopper’s paradise, only to declare in the same breath that they did not have the money to patronise any of these “high-class” shops.

Why, then, did people identify these places so readily? One reason was the yearning for a better life at a time when many were struggling to make ends meet, and the political and economic situation was uncertain. Eventually, by and large, the majority of the population did fare better in the subsequent decades as the economy prospered; people found that after paying for necessities, they had money left over to treat themselves to some of the finer things in life. Now they could afford to shop at places they had previously only dreamt about, thus fulfilling their long-cherished desires and aspirations, and advancing a step higher on the social ladder.1

Over the years, Singapore has become more and more of a consumerist society: the act of consumption – browsing, comparing and buying – as well as the goods and services that one buys, don’t just satisfy basic needs, but also convey style, prestige and social power.2 Today, going shopping for “fun”– getting a kick out of buying things, or enjoying the act of “going shopping” without the slightest urge to purchase anything – has become an acceptable pastime.

Looking back at the 1950s and 60s, it is not surprising that people think of Singapore’s shopping areas as culturally important, even though they did not “hang out” there as people do these days in Orchard Road, or they might acknowledge how small and unsophisticated these shops were compared with today’s swanky air-conditioned malls.3

This cultural shift is something to bear in mind as we take a closer look at these old shopping hubs. As focal points of cultural importance, what were they like, how are they remembered and what did they represent to people in the past (and perhaps, in the present as well)?

Raffles Place: For Western-Style Glamour

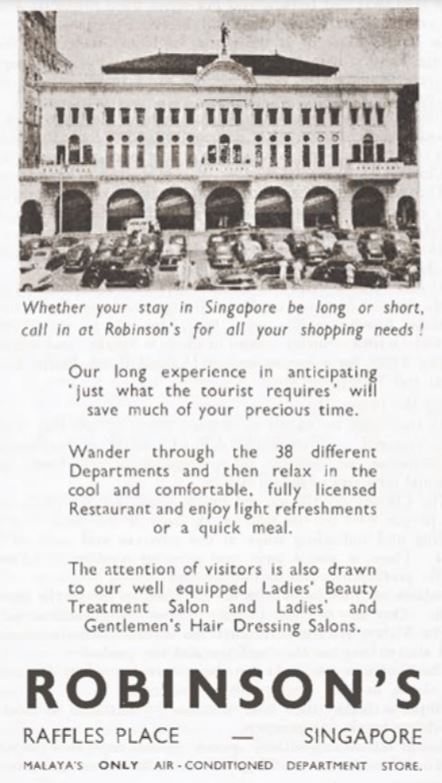

No one thinks of Raffles Place as a shopping destination these days, but it was once home to the grand dames of Singapore’s department stores: John Little & Co., established in 1845 (originally Little, Cursetjee & Co.) and Robinson & Co., established in 1858.4 Both originated as general stores that imported goods catering to European tastes, and chose Raffles Place for good reason – to be close to the prosperous European and Asian businesses and people with purchasing power.

By the 1950s, both department stores had become landmark shopping icons facing each other across Raffles Place, while a third establishment, Whiteaway, Laidlaw & Co., was just up the road beside Fullerton Square.5 Whiteaway’s – as it was commonly referred to – was the branch of a department store chain founded by two Scotsmen in Calcutta in 1882 and had been operating in Singapore since 1900.6

These three incumbents were, as Joseph Chopard recalls:

“… the only three European companies selling all the English goods, like everything under the sun: shoes, hats, all imported from England. John Little’s, Robinson’s and Whiteaway’s – all three within that area. There were [sic] no other place selling anything of that sort in Singapore….”7

It is worth remembering that department stores were a relatively new genre of merchandising then, not just in Singapore, but around the world. Following the advent of industrialised mass production in the West, department stores appeared in the 19th century in cities such as London, Paris, New York and Chicago, targeting middle- and upper-class female shoppers with a cornucopia of clothing and consumer goods, all attractively displayed in a comfortable and appealing setting to entice shoppers.8

In Singapore, these stores were “where all the rich and famous flocked” for the latest imported fashions, furniture, household items, groceries and tailoring services.9 The department store model was subsequently adopted by Asian entrepreneurs. Around 1935, Gian Singh & Co. was set up at Battery Road by five immigrant brothers from Punjab, India.10 The store later moved to a prominent location in Raffles Place opposite Robinson’s, next to which two of the brothers opened Bajaj Textiles.11

Both stores are often mentioned by name by oral history interviewees who used to work or live in the area. Victor Chew, whose office was near Raffles Place in the late 1950s and 60s, remembers that Gian Singh started out with sports goods before including textiles, leather goods and carpets too.12

To Richard Tan, who grew up in the 1960s: “Robinson’s has always been the store of all stores. … I still remember my first Monopoly set… it was like gold to get it, to buy it from Robinson’s.”13 On the other hand, Hugh Jamieson, who worked near Raffles Place in the late 1940s and 50s, recalls: “Robinson’s was regarded as the most reasonable, the cheapest of the lot. And of course they always had their annual sale.”14

Indeed, the annual Robinson’s sale is mentioned regularly by oral history interviewees because those were the only times they could afford to shop there. Kathleen Wang and her husband, for example, remember that the Robinson’s sale “is really a sale, cut the price more or less to about fifty percent”.15

On the morning of the sale, long queues of people would snake outside the store, eagerly waiting for it to open. The Singapore Standard and other newspapers would publish photographs of huge crowds at the annual sales events of Robinson’s, John Little and Gian Singh.

Ultimately, Robinson’s outlived its competitors at Raffles Place, even acquiring John Little in 1955. In 1960, the latter vacated its premises in the business district to open branches in other parts of Singapore (although the building remained until 1973 and its striking architectural façade inspired the design of the Raffles Place MRT station entrances).16

Whiteaway’s closed in 1962 due to “the approaching termination of lease and unsatisfactory trading results”. Similarly, Gian Singh folded the following year, not because of competition, but due to a protracted workers’ strike. Robinson’s alone thrived as a bastion of shopping at Raffles Place until 1972, when a massive fire – one of the worst in Singapore’s history – gutted the store.17 Robinson’s subsequently relocated to Orchard Road, and Raffles Place has been bereft of big-name department stores ever since.

Perhaps one reason why these department stores loom large in memory is that, over many decades, they became a recognisable presence at Raffles Place in terms of their architecture and cultural impact and, eventually, as a symbol of achievement and success – if one acquired the means to purchase the goods and services offered by these stores.

As Singapore’s commercial and financial sectors developed after World War II, more and more Asians worked in Raffles Place, and the area gradually lost some of its European patina. During lunch breaks, office workers would pass their time window shopping in the department stores, which although still expensive, were less forbidding than they had been to ordinary Singaporeans of an earlier generation.18

Tan Pin Ho recalls that even though the majority of Robinson’s customers in the 1960s were Europeans, its staff did not openly discriminate against Asian customers. Victor Chew, however, felt that the stores were “for the European crowd only” and did not make Asian or local customers feel welcome.19

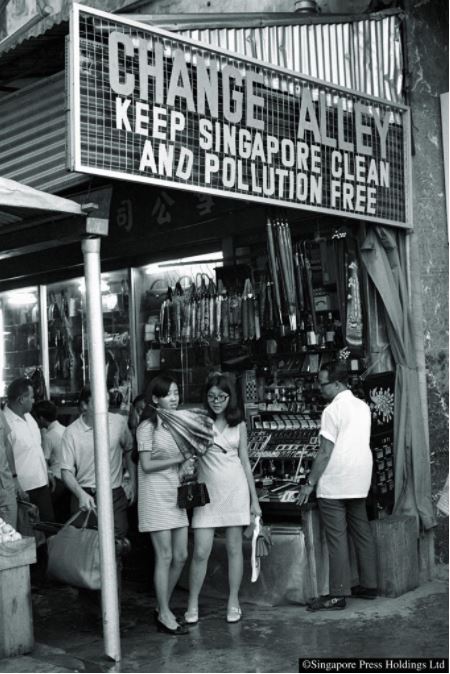

Change Alley: An Extraordinary Place

The only shopping icon in Raffles Place that rivals its department stores in terms of cultural memory was Change Alley. It was probably the most affordable (and popular) shopping destination of its time, yet it is remembered by many in less than glowing terms.

Change Alley was a narrow lane then, about 100 metres long and connecting Raffles Place with Collyer Quay, on more or less the same site that the Change Alley shopping arcade occupies today (though the latter is now a covered air-conditioned bridge raised above street level).

The old Change Alley was an important conduit for pedestrian traffic, and hosted a community with its own identity and life. In that respect, it is more vividly remembered than the Arcade (or Alkaff Arcade, as it was also referred to), a few buildings down the road. The latter, an impressive Moorish-style landmark that similarly linked Raffles Place with Collyer Quay, seems to have made less of an impression as a shopping location.

Change Alley was flanked by shophouses where people lived and worked, with “tiny one-room shops” on the ground level that sold all manner of goods, as well as makeshift stalls set up under tarpaulin. All were run by Chinese or South Asian shopkeepers.20 A tourist guidebook described the alley in colourful terms in 1962:

“In these narrow passageways you are increasingly hemmed in by merchandise of all sorts; you duck to avoid handbags swinging over your head, you swerve to avoid the salesman who is about to grasp your arm, you nearly trip over the small boy who is selling handkerchiefs at fantastically low prices or umbrellas[,] the price of which fluctuates with the state of the weather!”21

Unlike department stores, at Change Alley there were no fixed prices, inventories or currency exchange rates. Everything was up for bargaining. As Victor Chew puts it: “In Change Alley, if you don’t bargain you’re a fool”. Some remember that prices were typically half or less than half the price of similar items being sold at Robinson’s. According to Chew, depending on one’s bargaining skills, “you could either get a very good bargain or you could be cheated.”22

Price was not the only differential. As Change Alley stalwart, Albert Lelah of Albert Store, points out candidly:

“You go to departmental stores, what do you get…? The price is marked down there and you pay him and you walk. But here [at Change Alley] we can talk, we can laugh, we joke. They call us by names, we call them by names and they’re happy.”23

Besides office workers looking for watches, fountain pens, handbags or cheap textiles to make into office wear, there were also people who dropped by “practically every Saturday, just to walk up and down, and maybe pick up something”, as Hugh Jamieson remembers. Jon Metes went to the same shop in Change Alley so often to buy shoes for his wife that he “knew exactly the little cubbyhole in the wall ”24 where the shop was located and soon became a familiar face to the proprietor.

Depending on who you ask, Change Alley got its name either from the barter traders who gathered there in the late 19th century, or from the itinerant South Asian moneychangers who did business in the alley from at least the 1920s onwards. According to one source, its name was derived from a trading hub in London known as Exchange Alley (also sometimes referred to as Change Alley).25

Andrew Yuen, who grew up in the area in the 1950s and 60s, remembers moneychangers “wearing the sarong, or each one of them seemed to be wearing a coat with multiple pockets where they keep all the money. And usually they will flash around some foreign notes just to attract likely customers”.26

Change Alley was a prime location for the lively money exchange trade because most travellers then arrived by ship and disembarked at Clifford Pier – just a short hop across Collyer Quay. Whenever a ship was in port, tourists, sailors and military personnel would throng the place to exchange currency or buy souvenirs, knick-knacks and exotic “Oriental” products.

Between these visitors and local customers, the little lane would often be packed to the rafters, and filled with hustle and bustle. James Koh, who used to help out at his father’s shop at Change Alley, recalls: “It’s always congested, it’s always hot. But that added to the fun, I think, the atmosphere that tourists like.”27

It may have been the bargain-friendly tourist trade that made Change Alley less glamorous in the eyes of Singaporeans. Certainly, it was a different world from the air-conditioned, “spick and span and orderly” comfort of Robinson’s.28 As Tan Pin Ho describes it: “When you’re in Robinson’s you’re at home, but when you’re at Change Alley, you’re attending a party. Life is faster, faster, business is more brisk.”29

It was not a place for the faint-hearted. Victor Chew remembers that pickpockets were a perennial problem, while James Koh said that “when you walk along, of course there were all the sellers trying to get your attention, and in some cases they pulled the tourists into the shops”. Andrew Yuen was sympathetic to the tourists: “Usually these shopkeepers are sharks. They will fleece them [the buyers] … unless they also know the art of bargaining, then they get their money’s worth.”30

The sheer diversity of customers at Change Alley and its reputation as a slightly seedy sort of place may have discomfited some locals. Although Singapore was home to a multiracial and multicultural population, it was by no means as broadly cosmopolitan as it is today. Boey Kim Cheng mulls over in his poem “Change Alley”:

“… the stalls

spilling over with imitation wares

for the unwary, watches, bags

gadgets and tapes;

in each recess he heard the

conspiracies

of currencies, the marriage of

foreign tongues

holding a key to worlds opening on

worlds …”31

Those “foreign tongues” would have included French and Russian, among others. Mohamed Faruk, the owner of the Dinky-Di shop, recalls: “We deal with Australians, British, Italians and also Russians. All sorts, and we speak a little bit of every language, just to convince them to buy.” To offer a larger diversity of goods in his shop, Faruk would buy items from sailors who passed through Singapore regularly, such as watches, cameras and collectible items, and in turn sell them to his customers. He soon became known as a purveyor of Russian goods.32

The rough-and-tumble flavour that Change Alley acquired was far removed from the modern and sophisticated air of the department stores at Raffles Place. The alley could be drab and utilitarian at best on a good day, or noisy, stuffy, hot and sodden with rain on a bad one. In an essay on Change Alley, Boey offers readers a specific “scent-memory” of the place: “A musty, fusty, slightly urinous odour, a shade of age and decay fused with a sense of light, sunlight and the salt sea air that permeated the Alley.”33

After Change Alley was razed for urban renewal in 1989, some lamented that there was no place like it in Singapore any more.34 Yet despite its colour and what urban planners would now call a certain “vibrancy” – or rather, precisely because of it – Change Alley was not the sort of place that an upwardly mobile population would aspire to shop at. Instead, their hopeful gaze would turn to Robinson’s, dreaming of the day they could afford to shop there even if there wasn’t a sale.

Jalan-jalan at High Street and North Bridge Road

Across the Singapore River, a stone’s throw from the stately Supreme Court and the grimy wharves of Boat Quay, was the shopping district of High Street and North Bridge Road. Together with Hill Street, these were the first roads to be built after the British arrived, hosting an array of shops for Singapore’s European and Asian elites during the colonial period.35

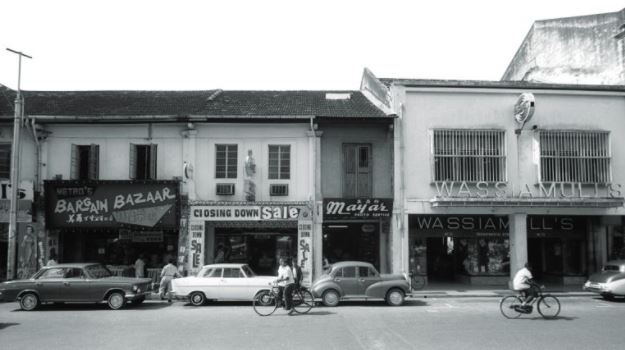

By the 1950s and 60s, these streets had become well known for shops and businesses owned by the South Asian community. Entrepreneurial Sindhis, Sinhalese, Gujaratis, Tamil Muslims and Sikhs established shops such as Wassiamull Assomull & Co. (established 1873; likely the first Sindhi trader in Singapore), Chotirmall, S.A. Majeed & Co., Khemchand and Sons, Pamanand Brothers, Modern Silk Store, Taj Mahal and Bajaj Textiles, which relocated here from Raffles Place.36

Girishchandra Kothari recalls there being “50 to 60 shops all catering to textiles, retail plus wholesale, and about 500 other textile wholesalers at the time in High Street alone, all Indians”.37 While these numbers are likely exaggerated, it nevertheless suggests that the area was already morphing into what we would today call a “shopping destination”.38

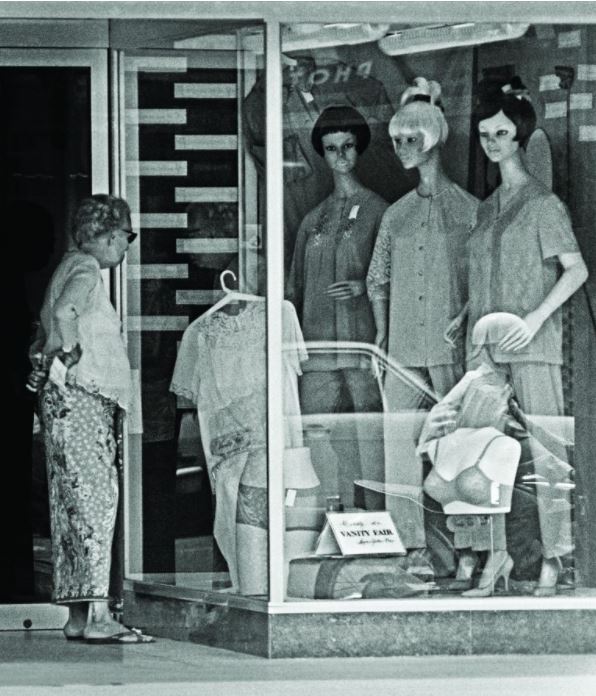

This was a time before ready-to-wear, off-the rack fashion became affordable for the masses. Instead, most families bought fabric by the yard to tailor-make their clothes at home, or engage the services of a professional tailor.

This was also the time when Singaporeans were becoming more exposed to Western popular culture, thanks to film and television, rock and roll music on the radio, and local fashion magazines such as Fashion, Fashion Mirror and Her World.39 With the music of Elvis Presley, the Supremes and Cliff Richard and the Shadows came magazines and photographs showcasing their hair and fashion styles.

By the mid-1960s, the world had been introduced to Mary Quant’s miniskirt, among other fashion trends. In Singapore, Chinese-language magazines, Lucky Fashion Magazine and Shee Zee Fashion, carried dress patterns so that budding fashionistas could sew their own miniskirts.40

High Street became the first port of call for people looking for all kinds of textiles, from durable cloth for everyday wear to the latest, flashiest fabrics to be sewn into trendy designs. Women were typically saddled with the responsibility of sewing or at least getting clothing tailored for their families. Many Singaporeans who were children in the 1960s – including at least three who became fashion designers – remember accompanying their mothers on these shopping expeditions.41

Stella Kon describes a typical shopping trip: “If I’m looking to buy some dress material, I start from the lower end of High Street and I walk up High Street and turn along North Bridge Road, shopping all the way.” Even Puan Noor Aishah, wife of Singapore’s first president, Yusof Ishak, frequented shops at High Street for fine silks and satins to make into outfits.42

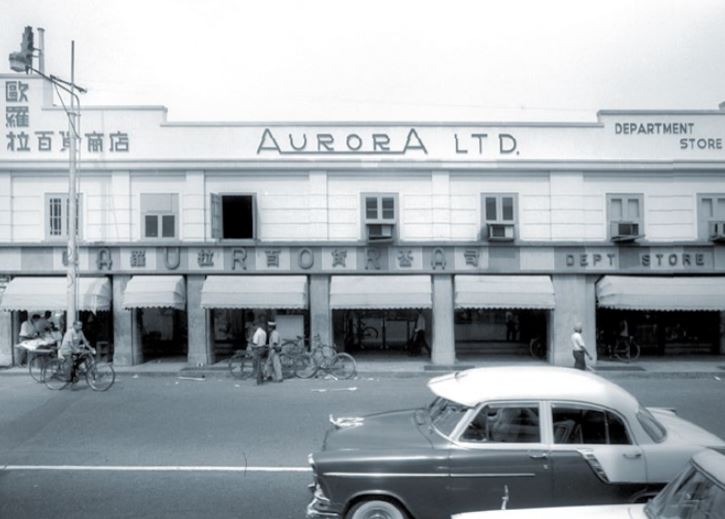

High Street also boasted of department stores to rival those at Raffles Place. Two had been around since the 1930s: Aurora, established by Tan Hoan Kie as the Singapore branch of a chain from Java and a landmark at the corner of High Street and North Bridge Road; and Peking, started by Kuo Fung Ting who was born in the Chinese capital, hence the name of his shop.43 Kuo decided to convert Peking from a curio shop into a department store in the 1950s when he realised that “after the war, the tendency would be for people to be more fashion-conscious. They would want more of the latest fashions in clothes, and other things synonymous with prosperity”.44

In 1957, Aurora and Peking were joined by the first Metro department store at High Street, set up by Ong Tjoe Kim, an immigrant from Xiamen, China, who had worked in department store chains in Java. A movie buff, he named his store after the Hollywood studio Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer and invited Hong Kong actress Li Mei to officiate at its grand opening.45 As one Singapore newspaper recalled in 1984, “the triangle among the three department stores – Aurora, Peking, and Metro – became a big attraction for the shoppers during the late 1950s”.46

Unlike the air-conditioned and somewhat sterile modern shopping mall experience that has become the norm in Singapore today, shopping at High Street was quite a different experience: people wandered in and out of individual shophouses, browsing or bargaining, and perhaps eventually buying.

Reminiscing about the area, Stella Kon says: “The picture that flashes in my mind is hot sunshine and dust and shadowy cool shops.”47 Besides the fashion boutiques, textile merchants and department stores, there was Ensign Bookstore, the legendary Polar Café, music stores such as TMA and Swee Lee, camera shops such as Ruby Photo and Amateur Photo Store, and Bata, an international shoe store chain of Czech origin at North Bridge Road. Many people remember Bata for selling affordable footwear – especially its trademark white canvas school shoes – to several generations of Singaporeans.48

Although the vibe and buzz of High Street appear to be warmly remembered by many, these shops, like the department stores at Raffles Place, were not within the financial reach of most Singaporeans. It is perhaps their aspirational significance that resonates more deeply among people than any specific purchase, as Lee Geok Boi reflects of her family’s visits to High Street: “Most of the time we couldn’t afford anything. But we went there to look anyway.”49

Looking and browsing, fingering and figuring out what one could buy for one’s dollar, or what one could afford (or not) were a visceral part of the Raffles Place or High Street shopping experience.

Although these shopping areas may have only been a shadow of London’s Carnaby Street – which encapsulated everything that was cool about 1960s fashion – they represented a desirable “Western type of shopping”, before the proliferation of shopping complexes in the 1970s and the development of Orchard Road into a shopping street.50

Today, in a city where ever more cookie-cutter shopping malls have come to dominate the landscape, with shops that parade a disconcertingly similar array of goods whether in swanky Orchard Road or suburban Yishun, it is not surprising that many first-generation Singaporeans look back to the time when they first encountered the idea of “going shopping” – and their memories of Raffles Place or High Street gleam all the more brightly.

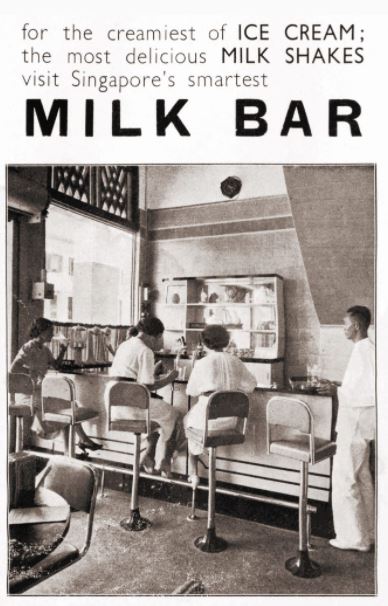

FANCY FOOD: CAFES & MILK BARS

For those who could afford it, shopping trips in the 1960s were often punctuated by pit stops at one of the fashionable Western-style cafés in town. The sentimental favourites that come up time and again in oral history interviews are Polar Café at 51 High Street and Magnolia Milk Bar at Capitol Theatre. Of the two, Polar Café was more established, having opened in 1925. By the 1960s, it was a favourite haunt of not only the lawyers and members of parliament who worked in the area, but also young people studying at nearby schools such as Raffles Institution.51 The café’s signature curry puffs became a much coveted treat for anyone in the area (including at least one member of Singapore’s first Cabinet), while its egg tarts, cakes and ice cream were also hugely popular.52

Magnolia Milk Bar, which opened almost immediately after World War II, was owned by local supermarket chain Cold Storage. Magnolia was Cold Storage’s house brand ice cream and manufactured locally from the 1930s. Magnolia Milk Bar served all kinds of ice cream concoctions and milkshakes as well as Western fare such as sandwiches, hot dogs and hamburgers.53

Cold Storage eventually ran several milk bars in Singapore (including one adjoining its supermarket in Orchard Road), but it was the air-conditioned outlet at Capitol that, by virtue of its location, won the hearts of many of Singapore’s baby boomers.54

As one Raffles Institution boy recalls, Magnolia Snack Bar occupied an iconic place in certain rituals of dating: teenagers often went out in groups for picnics or dances, after which a couple who fancied each other would go on one-on-one dates at Capitol and Magnolia. Another former customer aptly sums it up: “If I brought a girl there, it meant she was really special.”55

Magnolia was also where teachers treated their students to ice cream and friends met to celebrate over their Cambridge examination results. It became a place where an entire generation of Singaporeans picked up Western tastes and etiquette, right down to the proper use of cutlery. It wasn’t cheap though: in the 1960s, a full meal at Magnolia cost $5, compared to a bowl of noodles from a street hawker for 50 cents.56

Over at Raffles Place, there was a Honey Land Milk Bar, a casual snack bar at the corner of Raffles Place and Battery Road. Run by a Mr Tan, it sold ice cream, cream puffs, curry puffs and soft drinks. Victor Chew remembers that it was the only “soda fountain shop” or “ice cream parlour” in the area that sold deliciously frothy milkshakes. Although it was only a small place and had high stools for customers, it “did roaring business”.57

The really swanky eatery at Raffles Place was G.H. Café, a pre-war institution on Battery Road that was actually a bona fide restaurant with “white tablecloths and proper cutlery”. The origins of its name are speculative: some accounts say it began as the G.H. (Grand Hotel) Sweet Shop, another claimed it was named after a woman, Gertrude How, who used to run it. Whatever the case, G.H. Café was the lunchtime haunt of lawyers, shippers, traders and civil servants.58 Such was the café’s draw that it was even memorialised in Singaporean author and poet Goh Poh Seng’s first novel, If We Dream Too Long (1972):

“The restaurant was air-conditioned, had plush, upholstered chairs, white tablecloths, occasionally stained, and a fat Indian woman at the piano, singing old Broadway hits. Cole Porter, Oscar Hammerstein and Richard Rodgers ghosted the large, comfortably darkened dining room, while young business executives and lawyers and doctors ate from plates with knife and fork and spoon.”59

Yu-Mei Balasingamchow is the co-author of Singapore: A Biography (2009) and works on history, art and culture projects. She writes fiction and has also curated exhibitions for the National Museum of Singapore and the National Archives of Singapore. Her website is www.toomanythoughts.org.

Yu-Mei Balasingamchow is the co-author of Singapore: A Biography (2009) and works on history, art and culture projects. She writes fiction and has also curated exhibitions for the National Museum of Singapore and the National Archives of Singapore. Her website is www.toomanythoughts.org.

NOTES

-

This reflects the “internal narrative” of “progress, about overcoming hardship and ultimate triumph”, discussed by sociologist Teo You Yenn. It is a personal narrative that maps onto the national narrative of economic growth and prosperity; it is not uncomfortable for some to talk about past experiences of poverty “because one knows that one is accepted to have climbed and arrived.” See Teo, Y.Y. (2018). This is what inequality looks like (pp. 20–21, 226–227). Singapore: Ethos Books. (Call no.: RSING 305.095957 TEO) ↩

-

Wharton, C. (2015). Advertising: Critical approaches (p. 182). Abingdon, Oxon; New York, NY: Routledge. (Call no.: 659.1 WHA-[BIZ]). See also Chua, B.H. (1984, December 2). The High Street of our lives. The Straits Times, p. 20. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

See for instance Zarina Yusof. (Interviewer). (2002, July 22). Oral history interview with Lee Geok Boi; Chua, J.C.H. (Interviewer). (1997, November 3). Oral history interview with Victor Chew Chin Aik [Transcript of MP3 recording no. 001965/07/05, pp. 45-46]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

National Library Board. (2016, August 4). John Little written by Chia, Joshua Yong Chia & Tay, Shereen. Retrieved from Singapore Infopedia; National Library Board. (2014). Robinson’s Department Store is established. Retrieved from HistorySG. ↩

-

The buildings of John Little’s, Robinson’s and Whiteaway’s used to be on the sites now occupied by, respectively, the Singapore Land Tower, One Raffles Place and Maybank Tower. See Chia, S.-A. (2016, July–September). Bygone brands: Five names that are no more. BiblioAsia, 12 (2). Retrieved from BiblioAsia website; Remember Singapore. (2014, July 28). Raffles Place, 50 years of transformation. Retrieved from Remember Singapore website. ↩

-

Makepeace, W., Brooke, G.E., & Braddell, R.St.J. (Eds.). (1991). One hundred years of Singapore (Vol. 1, p. 234). Singapore: Oxford University Press. (Call no.: RSING 959.57 ONE-[HIS]) ↩

-

Chew, D. (Interviewer). (1985, May 27). Oral history interview with Joseph Henry Chopard [Transcript of MP3 recording no. 000561/21/05, p. 61]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

For more on the history of department stores, see Whitaker, J. (2011). The department store: History, design, display. London: Thames & Hudson. (Call no.: RBUS 381.141 WHI-[BIZ]; Blakemore, E. (2017, November 22). How 19th-century women used department stores to gain their freedom. Retrieved from History network website; Glancey, J. (2015, March 26). A history of the department store. Retrieved from BBC Culture website. ↩

-

Ruzita Zaki. (Interviewer). (1996, November 14). Oral history interview with Mrs Mohamed Siraj [Transcript of MP3 recording no. 001663/36/05, p. 61]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website ↩

-

The brothers were Hardial Singh, Inder Singh, Harbans Singh, Hira Singh and Balwant Singh. See Sidhu, R.S. (2017). Singapore’s early Sikh pioneers: Origins, settlement, contributions and institutions (pp. 130–131). Singapore: Central Sikh Gurdwara Board. (Call no.: RSING 305.8914205957 SID) ↩

-

Sidhu, 2017, p. 130; New textile firm opens. (1947, July 6). The Sunday Tribune, p. 2; Useful tips around Singapore shops. (1947, July 2). The Singapore Free Press, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Oral history interview with Victor Chew Chin Aik, 3 Nov 1997, p. 45; Chatfield, G.A. (1962). Shops and shopping in Singapore (p. 8). Singapore: D. Moore for Eastern Universities Press. (Call no.: RCLOS 959.51 CHA) ↩

-

Zaleha bte Osman. (Interviewer). (1999, April 14). Oral history interview with Richard Tan Swee Guan [Transcript of MP3 recording no. 002108/08/03, p. 48]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

Lee, P. (Interviewer). (1997, November 3). Oral history interview with Hugh William Jamieson [MP3 recording no. 001968/02/02]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

Zaleha bte Osman. (Interviewer). (1997, October 17). Oral history interview with Wang Kathleen Chwee Keng (Mrs), Wang Esther [Transcript of MP3 recording no. 001955/04/01, p. 4]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

National Library Board, 4 Aug 2016; Little’s Building (sold for $28m) to be pulled down. (1973, April 22). The Straits Times, p. 13; Dhaliwal, R. (1987, April 10). Journey into the past at Raffles Place MRT stop. The Straits Times, p. 32. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Whiteaway Laidlaw to close in Singapore. (1961, December 28). The Straits Times, p. 6; Gian Singh store to close down. (1963, November 2). The Straits Times, p. 6. Retrieved from NewspaperSG; National Library Board. (2016). Robinsons Department Store written by Yew, Peter Guan Pak. Retrieved from Singapore Infopedia ↩

-

Mohinder Singh, for instance, recalled that in the 1930s, “Asiatics generally won’t go there [to Robinson’s or John Little’s]”, while Joseph Chopard said, “In the old days, to go to Robinson’s you got to have a coat and all that sort of business. Our attire those days was a coat. … If you go about like this, they’ll call you a scruff or I don’t know what.” See Pitt, K.W. (Interviewer). (1985, September 6). Oral history interview with Mohinder Singh [Transcript of MP3 recording no. 000546/65/57, p. 576]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. Oral history interview with Joseph Henry Chopard, 27 May 1985, p. 60. ↩

-

Chua, J.C.H. (Interviewer). (1997, November 3). Oral history interview with Tan Pin Ho [Transcript of MP3 recording no. 001864/03/01, p. 8]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website; Oral history interview with Victor Chew Chin Aik, 3 Nov 1997, p. 48. ↩

-

Lee, P. (Interviewer). (1997, October 23). Oral history interview with Andrew Yuen [MP3 recording no. 001962/06/01]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website; Liu, G. (1999). Singapore: A pictorial history, 1819–2000 (p. 271). Singapore: Archipelago Press in association with the National Heritage Board. (Call no.: RSING 959.57 LIU-[HIS]); Lee, P. (Interviewer). (1997, October 23). Oral history interview with Andrew Yuen [MP3 recording no. 001962/06/03]; Chua, J.C.H. (Interviewer). (1997, November 3). Oral history interview with Tan Pin Ho [Transcript of MP3 recording no. 001864/03/02, p. 25]; Lim, J. (Interviewer). (2008, May 16). Oral history interview with James Koh Cher Siang [Transcript of MP3 recording no. 002847/06/01, p. 3]; Chua, J.C.H. (Interviewer). (1997, November 3). Oral history interview with Tan Pin Ho [Transcript of MP3 recording no. 001864/03/03, p. 31]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

Chua, J.C.H. (Interviewer). (1997, November 3). Oral history interview with Victor Chew Chin Aik [Transcript of MP3 recording no. 001965/07/06, p. 61]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website; Oral history interview with Wang Kathleen Chwee Keng (Mrs), Wang Esther, 17 Oct 1997, p. 4; Oral history interview with Mohinder Singh, 6 Sep 1985, p. 576; Oral history interview with Victor Chew Chin Aik, 3 Nov 1997, p. 50. ↩

-

Chew, D. (Interviewer). (1983, September 11). Oral history interview with Albert Abraham Lelah [Transcript of MP3 recording no. 000296/10/07, p. 88]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

Oral history interview with Tan Pin Ho, Nov 1997, p. 25; Oral history interview with Albert Abraham Lelah, 11 Sep 1983, p. 85; Oral history interview with Victor Chew Chin Aik, 3 Nov 1997, pp. 47-48; Oral history interview with Hugh William Jamieson, 3 Nov 1997; Lee, P. (Interviewer). (2002, May 21). Oral history interview with Jon Metes [MP3 recording no. 002657/15/13]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

National Library Board. (1999). Change Alley written by Lim, Fiona & Cornelius, Vernon. Retrieved from Singapore Infopedia; Savage, V.R., & Yeoh, B.S.A. (2013). Singapore street names: A study of toponymics (p. 69). Singapore: Marshall Cavendish Editions. (Call no.: RSING 915.9570014 SAV-[TRA]) ↩

-

Lee, P. (Interviewer). (1997, November 3). Oral history interview with Yuen Andrew Kum Hong [MP3 recording no. 001962/06/02]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

Oral history interview with James Koh Cher Siang, 16 May 2008, p. 2. ↩

-

Oral history interview with Victor Chew Chin Aik, 3 Nov 1997, p. 50. ↩

-

Oral history interview with Tan Pin Ho, 3 Nov 1997, p. 22. ↩

-

Oral history interview with Victor Chew Chin Aik, 3 Nov 1997, p. 51; Oral history interview with James Koh Cher Siang, 16 May 2008, p. 3; Oral history interview with Yuen Andrew Kum Hong, 3 Nov 1997. ↩

-

Boey, K.C. (2013, September 30). Change Alley: A poem. Retrieved from Singapore Memory Project website. ↩

-

Oral history interview with James Koh Cher Siang, 16 May 2008, p. 3; Lee, P. (Interviewer). (2006, September 1). Oral history interview with Mohamed Faruk [Transcript of MP3 recording no. 003021/01/01, pp. 22, 27, 32, 34]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website; Boey, 30 Sep 2013; The Ultimate Junk Store… Dinky Di Store. (2010, November 3). Retrieved from JustaClickin’ blog. For more details, see Boey, K.C. (2009). Change Alley. In Between stations: Essays (pp. 144–149). Artarmon, N.S.W.: Giramondo. (Call no.: RSING S821 BOE) ↩

-

Change Alley to close for good on April 30. (1989, April 19). The Straits Times, p. 19. Retrieved from NewspaperSG; Oral history interview with James Koh Cher Siang, 16 May 2008, p. 2. ↩

-

High Street was the first to be macadamed or paved with stones, earning it the title of the oldest street in Singapore. See National Library Board. (2018). High Street written by Cornelius, Vernon. Retrieved from Singapore Infopedia. ↩

-

Rai, R. (2014). Indians in Singapore, 1819–1945: Diaspora in the colonial port city (pp. 119, 118). New Delhi: Oxford University Press. (Call no.: RSING 909.049141105957 RAI). For more on the Sindhi traders’ role as “‘global middlemen’ between the Far East and India”, see Rai, 2014, pp. 107–108; Bhattacharya, J. (2011). Beyond the myth: Indian business communities in Singapore (pp. 48–50). Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. (Call no.: RSING 338.708991405957 BHA). The first mention in The Straits Times of Bajaj Textiles being at High Street was in 1954. See ‘Her first cigarette’ makes a good study. (1954, September 12). The Straits Times, p. 14. The last mention of Bajaj Textiles in The Straits Times was in an advertisement taken out by the Sikh business community in 1986. See Page 10 advertisements column 1. (1986, April 13). The Straits Times, p. 10. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Chew, D. (Interviewer). (1985, May 8). Oral history interview with Girishchandra Kothari [Transcript of MP3 recording no. 000549/23/14, p. 151]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website; cited in Bhattacharya, J. (2016). Less remembered spaced and interactions in a changing Singapore: Indian business communities in the post-independence period. In G. Pillai & K. Kesavapany (Eds.), 50 years of Indian community in Singapore (p. 85). Singapore: Hackensack, NJ: World Scientific. (Call no.: RSING 305.89141105957 FIF) ↩

-

The phrase “shopping destination” did not appear in Singapore’s English-language press until a luxury brand advertisement in 1979. See Page 7 advertisements column 1. (1979, July 23). The Straits Times, p. 7. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Yeo, Z. (2017, October–December). The way we were: Fashion through the decades. BiblioAsia, 13 (3); Yak, J., & Balasubramaniam, S. (2014, October–December). In vogue: Singapore fashion trends from 1960s to 1990s. BiblioAsia, 10 (3), 56–60; Ong, C., et al. (2016, January–March). 1960s fashion: The legacy of made-to-measure. BiblioAsia, 12 (4). Retrieved from BiblioAsia website. ↩

-

Yak & Balasubramaniam, Oct–Dec 2014, pp. 56–60. ↩

-

See for instance Teo, K.G. (Interviewer). (2013, November 13). Oral history interview with Christopher Choo Sik Kwong [MP3 recording no. 003828/13/01]; Sian, E.J. (Interviewer). (2010, January 18). Oral history interview with Francis Cheong [Transcript of MP3 recording no. 003444/04/01, pp. 6–7]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website; National Library Board. (2014). Hands: Gift of a generation (p. 70). Retrieved from BookSG; Ng, W.S. (1960). Weng’s memories. Retrieved from Singapore Memory Project website; Lee, D. (1989, October 21). From the sixties to SODA. The Business Times, p. 18. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Low, M. (Interviewer). (2006, April 13). Oral history interview with Stella Kon [MP3 recording no. 002996/36/12]; Tan, L. (Interviewer). (2001, May 22). Oral history interview with Mrs Jean Leembruggen [Transcript of MP3 recording no. 002534/12/02, p. 20]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

Where to shop in Singapore: No. III, – High Street. (1939, May 3). The Singapore Free Press, p. 12; Singapore new department store opens. (1938, October 14). The Malaya Tribune, p. 20; Chairman began his career as apprentice. (1965, April 2). The Straits Times, p. 12. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The Straits Times, 2 Apr 1965, p. 12. ↩

-

Ong, T.K. (1984, August 13). ‘Sinkeh’ who became king of dept stores. The Singapore Monitor, p. 10. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The Singapore Monitor, 13 Aug 1984, p. 10; See also Metro – past, present and into the future. (1982, September 9). The Business Times, p. 7. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Oral history interview with Stella Kon, 13 Apr 2006. ↩

-

Oral history interview with Victor Chew Chin Aik, 3 Nov 1997; Big new Singapore store. (1938, July 24). The Straits Times, p. 1; BATA’s new premises. (1940, June 26). The Malaya Tribune, p. 4. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Oral history interview with Lee Geok Boi, 22 Jul 2002, p. 15. ↩

-

Oral history interview with Victor Chew Chin Aik, 3 Nov 1997, p. 51. ↩

-

Chia, M. (1987, December 20). A grand old lady dons new clothes. The Straits Times, p. 4. Retrieved from NewspaperSG; Chua, J.C.H. (Interviewer). (1996, May 14). Oral history interview with Khoo Kay Chai [Transcript of MP3 recording no. 001744/18/05, pp. 73–74]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

Oral history interview with Lee Geok Boi, 22 Jul 2002, p. 14; Oral history interview with Christopher Choo Sik Kwong, 13 Nov 2013; The Cabinet member in question was Dr Goh Keng Swee. See Lim, J. (Interviewer). (2009, June 18). Oral history interview with John Morrice [Transcript of MP3 recording no. 001910/02/02, p. 42]; Chua, J.C.H. (Interviewer). (2010, October 5). Oral history interview with Bernard Chen Tien Lap [Transcript of MP3 recording no. 002530/16/15, pp. 191–192]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website; Hoe, I. (1986, January 15). Polar Cafe closes shop. The Straits Times, p. 34. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Goh, C.B. (2003). Serving Singapore: A hundred years of Cold Storage, 1903–2003 (pp. 13, 24, 45). Singapore: Cold Storage. (Call no.: RSING 381.148095957 GOH); Magnolia milk bar. (1945, October 8). The Straits Times, p. 4; A sandwich? (1948, March 6). The Straits Times, p. 3; Cold Storage. (1974, April 29). The Straits Times, p. 3. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Yeo, G.L. (2005, April 9). Merry widows and sweet temptations. The Straits Times, p. 15. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Lim, J. (Interviewer). (2002, August 29). Oral history interview with Hwang Peng Yuan (P Y Hwang) [Transcript of MP3 recording no. 002597/18/04, p. 54]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website; Toh, B.N. (2002, August 17). Like the 60s again, as Magnolia returns. Today, p. 6. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Tan, A.B. (2006, August 9). Good ol’ sundaes. The Straits Times, p. 2; Lee, P. (1986, August 9). People. The Straits Times, p. 54. Retrieved from NewspaperSG; Today, 17 Aug 2002, p. 6. ↩

-

Oral history interview with Victor Chew Chin Aik, 3 Nov 1997, p. 46; See also Lee, P. (Interviewer). (1997, October 23). Oral history interview with Yuen Andrew Kum Hong [MP3 recording no. 001962/06/04]; Lee, P. (Interviewer). (1997, November 3). Oral history interview with Hugh William Jamieson [MP3 recording no. 001968/02/01]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

Oral history interview with Hugh William Jamieson, 3 Nov 1997; Savage & Yeoh, 2013, p. 31; Lim, H.S. (Interviewer). (1981, July 2). Oral history interview with Rajabali Jumabhoy [Transcript of MP3 recording no. 000074/37/05, p. 37]; Oral history interview with Jon Metes, 21 May 2002; Lim, C.Y., & Tan, C.L. (2017). Lim Chong Yah: An autobiography: Life journey of a Singaporean professor (p. 68). Singapore: WS Professional. (Call no.: RSING 330.092 LIM) ↩

-

Goh, P.S. (1972). If we dream too long (p. 33). Singapore: Island Press. (Call no.: RSING 828.99 GOH) ↩