Our Home Sweet Home

Public housing is a Singapore success story, but the early years of high-rise living were sometimes a bittersweet experience. Janice Loo pores through the pages of Our Home magazine during its 17-year run.

One of the manifold challenges that Singapore faced at the time of self-governance in 1959 was a severe shortage of housing. Some 550,000 people, out of a population of nearly 1.6 million, had to make do with squalid living conditions, crammed into decrepit shophouses and squatter huts in the city centre and its outskirts.

To deal with the problem, the Housing and Development Board (HDB) was formed on 1 February 1960 and tasked with building as many flats as possible. Incredibly, by the end of its first decade, the board had completed over 100,000 units, providing affordable homes fitted with modern conveniences such as a ready supply of water and electricity as well as sanitation and waste disposal facilities, for nearly a third of the population.1

A nation of flat-dwellers was steadily taking shape, and probably unbeknownst to many at the time, Singapore would become a nation of high-rise homes and its public housing programme would one day be lauded by urban planners the world over. Between 1960 and 1970, the percentage of resident population living in HDB flats increased from 9 to 35 percent, rising further to 67 percent by 1980. The figure has remained above 80 percent since 1985.2

To ease Singaporeans into high-rise living, the HDB started its own magazine in July 1972 as a means of building rapport and staying connected with residents – then a community of 700,000 and counting.3

Our Home not only kept residents updated on HDB policies, initiatives, new amenities and happenings in housing estates, but also functioned as a “views-paper”4 where readers could express their opinions and ideas on various aspects of HDB living as well as hear from the board. Additionally, Our Home featured a variety of lifestyle topics such as cooking, health, fashion, interior decoration, sports and culture – in short “something for everyone in the family”.5

Starting with 147,000 copies, circulation grew in tandem with the number of new flats completed. By the time the last issue was published in August 1989, Our Home had made its way into 440,000 flats island-wide.

Keeping Up with the HDB

The magazine contents kept pace with the objectives of public housing which, over time, had evolved as societal needs changed. While the 1960s was all about quantity, the 70s saw a heavier emphasis on the quality of housing to meet the expectations of a more affluent and better educated populace.6

The “neighbourhood principle” continued to guide the planning of new estates and was further refined with the formulation of standards to optimise the size, type and location of ancillary facilities available to residents on their doorstep.7 This led to a new prototype town model based on a hierarchy of activity nodes, such as a town centre and neighbourhood centres and, later in the 1980s, precinct centres within the estate.8

Among the earliest examples highlighted in Our Home was Ang Mo Kio New Town, which comprised six neighbourhoods clustered around a town centre.9 Construction commenced in 1973.10 As the estate’s focal point, the town centre hosted a comprehensive range of amenities, including department stores, supermarkets, eating places, cinemas, a post office and even a public library.11 It became such a shoppers’ paradise that in 1980 one resident likened Ang Mo Kio town centre to a “busy Orchard Road, [albeit] on a smaller scale and without the traffic jams and expensive price tag”.12

Next in the hierarchy were neighbourhood centres with more basic facilities, such markets, hawker centres and shops, all within walking distance of homes.13 Apart from being one of the largest new estates of its time, Ang Mo Kio is the first to showcase HDB’s “new generation” flats.14 Compared to the ones built in the 1960s, these new flats were bigger and had improved features; the 3- and 4-room units, for example, had a storeroom, an ensuite master bathroom with a pedestal toilet, and bigger kitchens.15

The new town model was adopted in other estates built at the time, for example, Telok Blangah, Bedok and Clementi, which subsequently facilitated the rapid development of several new towns – Yishun, Hougang, Jurong East and West, Tampines and Bukit Batok – in quick succession from the late 1970s onwards.16 As neighbourhoods inevitably took on a cookie-cutter appearance, the visual identity of new towns became an important consideration at the planning stage.17

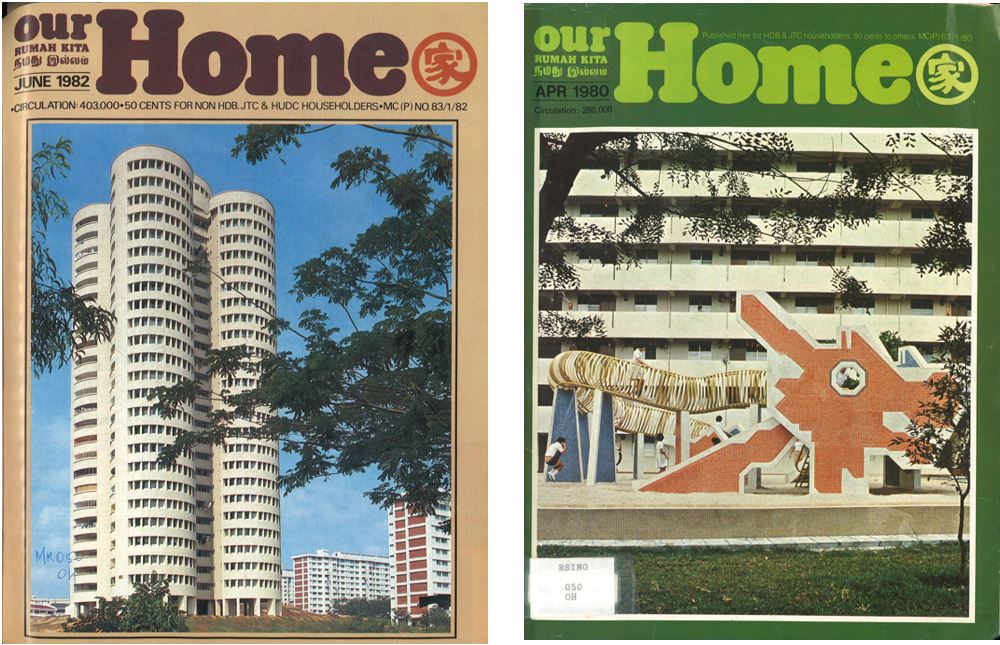

Attempts to inject character into public housing were showcased in Our Home, and its covers – once dominated by images of smiley, happy residents – began to feature design and architecture more prominently from 1979 onwards. The HDB introduced new block designs to create a stronger sense of place; for instance the cover of Our Home June 1982 issue showcased the unique 25-storey clover leaf-shaped circular point block at Ang Mo Kio Avenue 2.18

Articles also described how colours and architectural features lent identity to public housing estates, for example, how apricot-coloured bricks and pitched metal roofs defined the aesthetics of Tampines New Town, and how the colour scheme of roofs demarcated its nine neighbourhoods.19

Similarly, in Bukit Batok New Town, the repetition of splayed corners at the water-tank level, the ground levels, and along common corridors of blocks, enhanced the distinctiveness of the estate.20 HDB experimented with wall murals too; for example, one block in MacPherson sported a majestic rising sun whereas another in Hougang featured the grinning face of a wayang kulit (shadow puppet play) puppet.21

In addition, older estates were enhanced or redeveloped to ensure living conditions kept up with that of the new ones.22 New or upgraded amenities highlighted over the years included sports and swimming complexes, gardens and parks, commercial and shopping centres, markets and food centres, as well as community centres and facilities for social services.23

Even playgrounds came under the HDB’s scrutiny as it began to feature more dynamic elements like suspension bridges and climbing ropes to create a miniature adventureland for children.24 Grown-ups were not forgotten either as new fitness corners were rolled out with structures for sit-ups, push-ups, pull-ups, and other exercises.25

Our Home also took pains to explain the behind-the-scenes work of its public officers, such as housing and maintenance inspectors, sales clerical officers, operators from the Essential Maintenance Service Unit and Lift Rescue Unit, cleaners and their supervisors, and even the dreaded parking warden.

From Strangers to Neighbours

However, a house does not make a home, and a pleasant living environment cannot be achieved by design alone. As high-density public housing could potentially lead to tensions between neighbours, Our Home sought to forge a sense of commonality and responsibility among residents as a nation of house-proud flat-dwellers – or “heartlanders”26 as we know them today.27

More than a roof over their heads, the public housing programme fostered a sense of rootedness among Singaporeans by giving them a tangible stake in the country. The late founding Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew described it thus:

“I wanted a home-owning society. I had seen the contrast between the blocks of low-cost rental flats, badly misused and poorly maintained, and those of house-proud owners, and was convinced that if every family owned its home, the country would be more stable… I believed this sense of ownership was vital for our new society which had no deep roots in a common historical experience.”28

In its inaugural message to readers in July 1972, the magazine echoed Lee’s sentiments:

“Our Home is about you and others in HDB housing estates. You will get to know how much other people are like you, how other residents live, their problems and how they overcome them and about their achievements… We all live in the same community. It might be Redhill or Toa Payoh or Queenstown, what matters is that we make that community something to be proud of, a healthy environment for our children.”29

In line with Singapore’s first Concept Plan in 1971, residential estates were developed as part of a ring of self-contained new towns around the central water catchment area.30 High-rise flats began replacing kampongs (villages) and came to characterise the suburban landscape. Our Home charted this period of transition and gave voice to the hopes and frustrations of residents as they adjusted to their new environment.

A perennial complaint was noise. For those used to the relative quiet of rural kampongs, the cacophony of high-density estates could be hard to bear, what with screaming and crying children, blaring radio and television sets, not to mention the infernal clacking of mahjong tiles.31

One Our Home article in 1973 portrayed noise in a more positive light: as an expression of the informal communal life in estates. Writer Sylvia Leow traced the lively rhythm of everyday activities along the common corridor from the rush of residents heading to school, work and the market, to the boisterous sounds of playing children, and the chorus of itinerant vendors plying wares and services.32

The calls of the galah33 man and the knife-sharpening man might evoke wistfulness for a vanished soundscape, but it was a different situation then as one disgruntled resident of Holland Close wrote:

“After reading the article… I hate to say that I view the hustle and bustle as noise nuisance. I never knew that common corridors can bring about such headaches and frustrations until I recently moved into my flat. I am extremely distressed by the ‘noisy merriment’ of the corridor. Can you study under such [a] noise-polluted environment? I earnestly pray that those pedlars, children on tricycles, etc will disappear into thin air….”34

Such complaints created opportunities for the HDB to clarify its responsibilities HDB and those of the residents. Our Home made it clear that it was the duty of parents to teach children to play quietly and not cause mischief by urinating in the lifts or tampering with mailboxes.35 Problems like noise, vandalism, and littering could only be tackled if residents exercised consideration for the feelings and rights of their neighbours.

The more practical solution in the long term was to instil civic-consciousness. As a tool for public education, Our Home instructed residents on the dos and don’ts of HDB living. The topics ranged from the proper disposal of waste and bulky refuse, lift usage, and the drying of laundry to playing ball games in common spaces, the keeping of plants and pets, and crime and accident prevention.36

In addition, opinion pieces and letters from readers helped to define and reinforce good neighbourly behaviour. For example, in 1972, Pang Kee Pew of Alexandra estate wrote in to share how he reminded his wife to place a cloth pad under the mortar when pounding chillies – “a daily occurence in almost every home”37 – to reduce noise. For his part, Pang confessed that he was tempted to sweep the dust through the balcony gap whenever he swept the house and let it be blown into neighbouring flats. But Mrs Pang would step in and make sure that he swept the dust onto a piece of newspaper that was then folded up and disposed in the rubbish chute.

Above all, the goal was to make friends out of neighbours. As relocation disrupted existing social ties, it was not uncommon for former kampong dwellers to experience a loss of community.38 There was a tendency towards insularity, partly due to devices that provided endless hours of entertainment and allowed people to plug into the outside world without stepping out of their flats.39 Already in 1973, Leonard Lim of Commonwealth Drive observed:

“… there are others I know who have just shifted in and miss the warmth and friendliness of old neighbours and the rural way of life. These people now isolate themselves in their flats. They don’t make an effort to get to know their neighbours. Instead they rely on radios, stereograms and television to substitute for real-life contacts with neighbours.”40

One opinion piece in 1972 defined the ideal type of neighbourly relations in HDB estates as one of warm, amicable and relaxed give-and-take. When neighbours are friends, they willingly “respect each other’s right to enjoyment of peace, privacy and quiet [and] work together to build a clean, friendly and harmonious community”,41 thus reducing estate-management problems in the long-run.42

To encourage residents to know their neighbours better, Our Home highlighted artists, sculptors, writers and other interesting personalities living in their midst.43 ln addition, from the June 1981 issue onwards, the magazine featured an “RC Corner” to promote the activities of the Residents’ Committees (RCs) and voluntary organisations run by and for residents to promote community spirit and neighbourliness in HDB housing estates.

High-rise Paradise

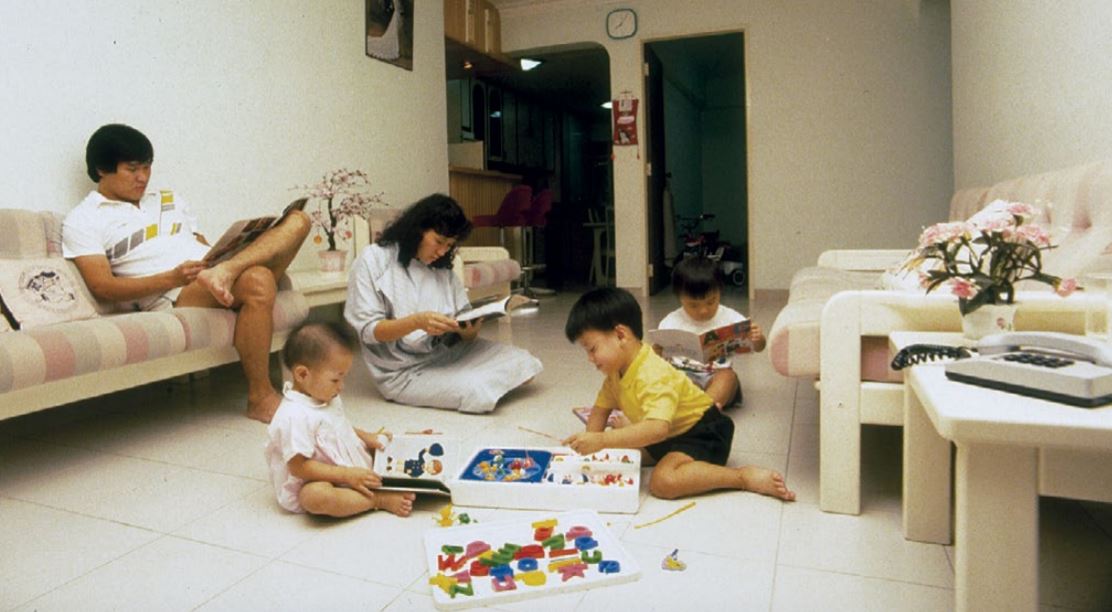

Notwithstanding the complaints, many residents were generally quite happy with HDB living. One of those who expressed her appreciation was “Mei-Mei” from Toa Payoh in 1972. Having grown up in “one of those rambling bungalows in the countryside”, she was initially apprehensive of the limited space in a flat. However, after two years she had become accustomed to her “62 sq. m. of living room, bedroom and kitchen [which] are more than ample for [her] needs”. Mei-Mei urged readers to look on the bright side:

“On the other side of the coin, be thankful that you only have a small area to furnish. House-owners in private estates inevitably have too much space… To be downright practical, who really needs acres of floors to scrub and mountains of dust to sweep when you can live comfortably in a flat which needs only a flick of the duster to emerge sparklingly clean… We might complain when shops ply a noisy trade downstairs but let’s look at it this way. Which housewife can boast of having her market, her cobbler, her carpenter, her hair-dresser and even her doctor, dentist and banker all within easy walking distance?”44

She went on to list more advantages, such as round-the-clock essential maintenance services, the panoramic view from her home on the 11th floor, and the breeze which “makes for comfortable living all year round”. “Mei-Mei” stressed that her views were not unique but “echo the impressions of a growing community of satisfied flat-dwellers to whom ‘home sweet home’ is a reality”.

But “home sweet home” did not come without effort. Moving into a HDB flat meant increased costs. Besides the mortgage repayments, there were utilities, furnishings, household appliances and other consumer durables to pay for.45 Home ownership and the desire for a better quality of life in turn propelled more people into the workforce and the consumer economy, thus creating the start of an industrialised society.46

(Centre) An advertisement showing a family in the living room of their HDB flat with various SONY home entertainment appliances. Television vieiwing, including video, had become the most popular leisure activity by the 1980s. Image reproduced from Our home, December 1972, back cover.

(Right) Hitachi touting its new washing machine as the “modern HDB’ washerwoman’”. Washing machines became more common in HDB households from the mid-1970s due to their affordability and difficulty of employing reliable washerwoman. Image reproduced from Our Home, October 1975, p. 2.

Significantly, women began entering the workforce in greater numbers to supplement the household income, made easier by the plethora of employment opportunities at their doorstep. Another element in the planning of housing estates was the allocation of land for light industrial use, which “has enabled many a housewife and school-leaver to walk to work and to acquire new skills, bringing home additional income for the family”.47

Multinational companies that set up production facilities in HDB neighbourhoods included Hitachi, which manufactured television sets along with washing machines at its Bedok factory, and General Electric in Toa Payoh, which produced digital and clock radios.48 In 1972, more than half of the employment within HDB estates was generated by the industrial sector, with women making up 72 percent of its workforce.49

A feature on young industrial workers in Our Home demonstrated how employment strengthened the socio-economic position of women and gave them an avenue for advancement beyond their traditional domestic roles. Readers were introduced to 25-year-old Yen Khuan Thai, who started work as a camera assembly line operator at the Rollei factory in Alexandra in 1971, and went on to do data-processing at the company’s new factory in Chai Chee.

Yen found the work “interesting and challenging”, and did not mind the distance between her home in Queenstown to the factory in the east as there was “ample scope for advancement and further training”. She earned a monthly income of $300, not a paltry sum given that the average monthly household income of HDB residents was $469 in those days. Working women thus went a long way in helping families afford the trappings of the HDB lifestyle.50

As the magazine with the largest circulation in Singapore, Our Home was an avenue for brands to “penetrate more homes to reach more target consumers”.51 Advertisements in Our Home reflected and shaped the tastes and aspirations of flat-dwellers – the ownership of consumer durables being an indicator of relative affluence and living standards.

Advertisements held out the dream of a perfect home and a new level of well-being that could be achieved with consumer technology. Washing machines, rice cookers and vacuum cleaners would make domestic work less taxing and free up time for leisure, whereas television and radio sets enhanced the time spent at home, as these advertisements claimed:

“Make life easier with Sanyo home appliances…. Hundreds of home appliances roll off Sanyo assembly lines daily to help cut household drudgery to a bare minimum, [and] lessen the toil and increase the joy of living.52

“It’s nice to have a home of your own and fill it with lovely things… such as Sony. Sony makes your flat nice to come home to. There’s Sony television for clear reception anywhere; Sony stereo for listening pleasure and party sounds; Sony clock radio for the time and soothing background music, and a powerful world-wide Sony radio to keep you abreast with the world. All designed for superb entertainment and gracious living.”53

Modern conveniences were essential in transforming the flat into an oasis of rest and relaxation, a home to which people could retire to at the end of the day to savour the fruits of their labour.

Remembering Our Home

Our Home bid farewell to its readers in 1989. That year, town councils were established to take over the management of estates from the HDB, and they started their own newsletters for residents.54

The constant remaking of the heartland through redevelopment and upgrading has contributed to the current wave of nostalgia among Singaporeans for old playgrounds, wet markets, provision shops, cinemas and bowling alleys – many of which have been repurposed or no longer exist.

Our Home magazine not only serves as a chronicle of Singapore’s public housing history, but is also a window into the lives of those who grew up in the old estates of the 1970s and 80s – in those pivotal years when a young nation came into its own against all odds.

Janice Loo is a Librarian at the National Library, Singapore. Her responsibilities include collection management and content development as well as research and reference assistance on topics relating to Singapore and Southeast Asia.

Janice Loo is a Librarian at the National Library, Singapore. Her responsibilities include collection management and content development as well as research and reference assistance on topics relating to Singapore and Southeast Asia.

NOTES

-

Singapore. Housing and Development Board. (1970). First decade in public housing, 1960–69 (pp. 6–8, 10). Singapore: Housing and Development Board. (Call no.: RSING 301.54 HOU) ↩

-

Singapore. Housing and Development Board. (2017). Key statistics: Annual report 2016/2017 (p. 9). Retrieved from Housing and Development Board website. ↩

-

Singapore. Housing and Development Board. (1971). Annual report 1971 (p. 22). Retrieved from BookSG; Out: A journal for 140,000 in HDB flats. (1972, June 29). The Straits Times, p. 17. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. [Note: The magazine was distributed free-of-charge to all HDB householders, but cost 50 cents a copy to purchase for non-HDB dwellers. The quarterly publication became bi-monthly from January 1973. Although the magazine’s contents were mainly in English and Chinese, certain features such as the editorial and news items would also be published in Malay and Tamil.] ↩

-

Editorial. (1974, May–June). In Our Home (p. 5). Singapore: Housing and Development Board. ↩

-

Editorial. (1972, July). In Our Home (p. 14). Singapore: Housing and Development Board. Available via PublicationSG. ↩

-

Wong, A.K., & Yeh, S.H.K. (Eds.). (1985). Housing a nation: 25 years of public housing in Singapore (pp. 13, 384). Singapore: Housing and Development Board. (Call no.: RSING 363.5095957 HOU) ↩

-

Liu, T.K. (1975). Design for better living conditions. In S.H.K. Yeh (Ed.), Public housing in Singapore: A multidisciplinary study (pp. 152–153). (Call no.: RSING q363.5095957 PUB); The neighbourhood principle. (1975, January–February). In Our Home (pp. 32–33). Singapore: Housing and Development Board. ↩

-

Wong & Yeh, 1985, pp. 95–96, 104–105. ↩

-

Ang Mo Kio New Town. (1974, March–April). In Our Home (pp. 10–11). Singapore: Housing and Development Board. ↩

-

Singapore. Housing and Development Board. (1974). Annual report 1973/1974 (p. 45). Retrieved from BookSG. ↩

-

Ang Mo Kio Town Centre. (1976, December). In Our Home (p. 14); A town away from town… Ang Mo Kio Town Centre. (1980, October). In Our Home (p. 17); For other town centres, see Shopping made easy in Queenstown. (1974, September–October). In Our Home (pp. 10–11; New hubs of activity. (1976, October). In Our home (pp. 10–11); Bedok Town Centre. (1977, June). In Our Home (p. 20); Clementi Town Centre. (1978, October). In Our Home (pp. 4–5).; Bukit Merah Town Centre. (1979, April). In Our Home (pp. 10–11); Bukit Batok Town Centre. (1984, December). In Our Home (pp. 4, 11); Town centres – The hub of a HDB new town. (1985, August). In Our Home (pp. 12–14). Singapore: Housing and Development Board. ↩

-

Our Home, Oct 1980, p. 17. ↩

-

Our Home, Mar–April 1974, pp. 10–11; Wong & Yeh, 1985, p. 104; Also see Bedok Neighbourhood Centre. (1985, December). In Our Home (pp. 12–13). Singapore: Housing and Development Board. ↩

-

Our Home, Mar–April 1974, pp. 10–11. ↩

-

New generation flats. (1973, July–August). In Our Home (pp. 14–15); New generation flats revisited. (1975, August). In Our Home (pp. 18–19). Singapore: Housing and Development Board; Wong & Yeh, 1985, pp. 58–66. Also see Building better homes. (1987, December). In Our Home (pp. 12–13). Singapore: Housing and Development Board. ↩

-

Wong & Yeh, 1985, pp. 96, 98; Liu, 1975, pp. 124–125. Also see Telok Blangah New Town: Blue print for the future. (1973, January–February). In Our Home (pp. 14–15); A new town in the east. (1973, September–October). In Our Home (pp. 8–9); New town on the west coast. (1975, December). In Our Home (p. 13); Jurong East & West new towns. (1979, October). In Our Home (pp. 20–21); The first of Hougang New Town. (1980, April). In Our Home (pp. 16–17). Singapore: Housing and Development Board. ↩

-

Wong & Yeh, 1985, pp. 98, 106–107. ↩

-

Seven new facades. (1979, August). In Our Home (pp. 16–17). Singapore: Housing and Development Board. Available via PublicationSG; Wong & Yeh 1985, p. 108. ↩

-

Wong & Yeh, 1985, p. 108; Tampines New Town. (1982, December). In Our Home (pp. 16–17); Tampines New Town. (1985, June). In Our Home (pp. 12–13, 27). [Note: Tampines New Town is the first to fully implement the precinct concept, where its nine neighbourhoods are further subdivided into precincts of 600 to 1,000 households, or about 4,000 residents. This concept aims to foster neighbourliness where blocks in the same precinct are clustered around a focal point with social and recreational amenities that encourage interaction among residents]. Also see Identity blocks. (1984, April). In Our Home (pp. 12–13); Bishan New Town. (1984, December). In Our Home (pp. 12–13); Yishun New Town – One of the largest. (1985, February). In Our Home (pp. 12–14); Woodlands New Town. (1987, April). In Our Home (pp. 16–18). Singapore: Housing and Development Board. Available via PublicationSG. ↩

-

Bukit Batok New Town. (1984, August). In Our Home (pp. 4–5). Singapore: Housing and Development Board. Available via PublicationSG. Murals, murals on the walls…. (1981, June). In Our Home (pp. 12–13). [Note: The MacPherson block was featured on the cover of the October 1979 issue and the Hougang block on the cover of the June 1981 issue]. See also Our walls come alive. (1976, August). In Our Home (pp. 10–11); Vibrant graphics for Kaki Bukit Estate. (1986, October). In Our Home (pp. 16–17). Singapore: Housing and Development Board. ↩

-

Murals, murals on the walls…. (1981, June). In Our Home (pp. 12–13). [Note: The MacPherson block was featured on the cover of the October 1979 issue and the Hougang block on the cover of the June 1981 issue]. See also Our walls come alive. (1976, August). In Our Home (pp. 10–11); Vibrant graphics for Kaki Bukit Estate. (1986, October). In Our Home (pp. 16–17). Singapore: Housing and Development Board. ↩

-

New facilities in your neighbourhood. (1975, May–June). In Our Home (pp. 12–13); Old estates – what’s new. (1979, December). In Our Home (pp. 16–17, 29). Singapore: Housing and Development Board. ↩

-

Examples, sports facilities: Our sports complexes. (1974, September–October). In Our Home (p. 13); When taking a dip can be so convenient… (1981, April). In Our Home (pp. 14–15, 24); Sports facilities for residents in Ang Mo Kio. (1986, June). In Our Home (pp. 16–17); Gardens and parks: Toa Payoh Town Garden. (1974, July–August). In Our Home (pp. 9–11); 3 new town gardens at Ang Mo Kio, Woodlands and Clementi. (1982, October). In Our Home (pp. 16–18); Scenic Yishun. (1987, June). In Our Home (pp. 16–17); Commercial and shopping centres: One stop shopping is here to stay. (1974, January–February). In Our Home (pp. 24–25); New commercial hub at Joo Chiat. (1974, November-December). In Our Home (pp. 12–13); HDB’s first air-con complex. (1980, December). In Our Home (pp. 16–17); Markets and food centres: Good food centres. (1975, December). In Our Home (pp. 10–11); Dry markets. (1986, February). In Our Home (pp. 6–7, 32); Community facilities and social services: Community living: HDB to build 40 community centres. (1979, April). In Our Home (pp. 16–17, 30); Chua, B.H. (1981, June). Social service centres in HDB estates. In Our Home (p. 10); Health services for the elderly. (1986, August). In Our Home (p. 21). Singapore: Housing and Development Board. ↩

-

New play companions. (1975, January–February). In Our home (pp. 16–17); New design playgrounds. (1979, February). In Our Home (pp. 16–17, 29); Also see It’s play time. (1981, October). In Our Home (pp. 10–11). The article mentioned the “Spacenet”, a play structure created from a web of ropes in Ang Mo Kio that was imported from the US at a cost of $26,000. ↩

-

HDB’s innovation in fitness thinking. (1979, October). In Our Home (pp. 16–17). Singapore: Housing and Development Board. ↩

-

The term was coined by then Minister for Information and the Arts George Yeo during the Q&A session at his inaugural National University of Singapore Society Lecture in June 1991. The “heartland” refers to the public housing estates, with “heartlander” meaning a flat-dwelling Singaporean. ↩

-

Kong, L., & Yeoh, B.S.A. (2003). The politics of landscapes in Singapore: Constructions of “nation” (pp. 96–97). New York: Syracuse University Press. (Call no.: RSING 320.95957 KON) ↩

-

Lee, K.Y. (2000). From third world to first: The Singapore story, 1965–2000: Memoirs of Lee Kuan Yew (pp. 116–117). Singapore: Times Editions and Singapore Press Holdings. (Call no.: RSING 959.57092 LEE-[HIS]) ↩

-

Our Home, Jul 1972, p. 14. ↩

-

Urban Redevelopment Authority. (2018, May 10). Past concept plans. Retrieved from Urban Redevelopment Authority website. ↩

-

Noise. (1974, July-August). In Our Home (pp. 12–13). Singapore: Housing and Development Board. Available via PublicationSG; Tai, C.L. (1988). Housing policy and high-rise living: A study of Singapore’s public housing (p. 135). Singapore: Chopmen Publishers. (Call no.: RSING 307.336095957 TAI) ↩

-

Leow, S. (1973, September–October). Corridor traffic. In Our Home (p. 33). Singapore: Housing and Development Board. ↩

-

The “galah” (in Malay) or “tek-ko” (in Hokkien) man sold bamboo poles commonly used for drying clothes. ↩

-

Quiet please! (1974, March–April). In Our Home (p. 14). Singapore: Housing and Development Board. ↩

-

[Untitled] [Letters to HDB]. (1972, October). In Our Home (p. 7); [Untitled] [Letters to HDB]. (1973, January–February). In Our Home (p. 7). This view was shared by other residents as well, see Mini-bins. (1974, January–February). In Our Home (p. 8); Lift vandalism. (1974, March–April). In Our Home (p. 34); Noise pollution. (1974, May–June). In Our Home (p. 29). Singapore: Housing and Development Board. ↩

-

See, for example, Refuse collection and you. (1978, February). In Our Home (pp. 10–11); Dispose of your swill the proper way. (1981, April). In Our Home (p. 6); The correct way to dispose refuse. (1982, April). In Our Home (p. 32). Singapore: Housing and Development Board; There is a proper place for junk. (1985, February). In Our Home (pp. 6–7, 19); Lily the lift. (1974, March–April). In Our Home (pp. 14–15); Good lift service comes with care. (1986, August). In Our Home (pp. 18–19); Washing day advice. (1977, December). In Our Home (pp. 22–23); Ballgames in HDB estates. (1978, February). In Our Home (pp. 4–5); If you keep potted plants. (1978, June). In Our Home (pp. 3–4); On household pets in HDB flats. (1978, December). In Our Home (pp. 12, 28); Making the home safe. (1973, March–April). In Our Home (pp. 10–11, 35); Security in high rise flats. (1978, August). In Our Home (pp. 6–7). Singapore: Housing and Development Board. ↩

-

Be considerate. (1972, December). In Our Home (p. 18). Singapore: Housing and Development Board. ↩

-

Riaz Hassan. (1977). Families in flats: A study of low income families in public housing (p. 144). Singapore: Singapore University Press. (Call no: RSING 301.443095957 HAS) ↩

-

Multi-storey success. (1973, May–June). In Our Home (p. 36). Also see 走出菜芭 [From farm to flat]. (1974, January–February). In Our Home (p. 33), for the perspective of a new resident who formerly lived in a kampong in Potong Pasir. ↩

-

Friendship is a chain that links people together… (1972, December). In Our Home (p. 6). Singapore: Housing and Development Board. ↩

-

Kong & Yeoh, 2003, pp. 96–97. ↩

-

See, for example, 祖屋圈内:雕塑家林浪新 [Profiles: Sculptor Lim Nang Seng]. (1973, July–August). In Our Home (p. 41); Inside an artist’s home [Batik artist Yusman Aman]. (1973, September–October). In Our Home (pp. 22–23); Crab~seller turned artist [Tay Bak Koi]. (1974, March–April). In Our Home (pp. 26–27); Scrap-iron sculpture [Tan Teng Kee]. (1975, January–February). In Our Home (pp. 22–23); His ceramic world [Iskandar Jalil]. (1975, May–June). In Our Home (p. 24); Pelukis dengan alamnya yang romantik: Abdul Ghani Hamid [The artist and his romantic world: Abdul Ghani Hamid]. (1986, February). In Our Home (pp. 26–27, 32). Singapore: Housing and Development Board. ↩

-

Happiness is… living in a flat. (1972, December). In Our Home (pp. 31–33). Singapore: Housing and Development Board. Available via PublicationSG. ↩

-

Salaff, J.W. (1988). State and family in Singapore: Restructuring a developing society (pp. 28–30). Ithaca: Cornell University Press. (Call no.: RSING 306.85095957 SAL) ↩

-

Chua, B.H. (1997). Political legitimacy and housing: Stakeholding in Singapore (pp. 160–161). London; New York: Routledge. (Call no.: RSING 363.585 CHU) ↩

-

Employment at your doorstep. (1974, May–June). In Our Home (p. 11). Singapore: Housing and Development Board. ↩

-

Our Home, May–June 1974, p. 11. Vacancies for production operators were advertised in Our Home. See, for example, the inside back cover (Texas Instruments) and back cover (National Semiconductor) of the May–June 1973, as well as page 6 of the Nov–Dec 1973 issue (Rollei). ↩

-

Singapore. Housing and Development Board. (1972). Annual report 1972 (p. 33). Retrieved from BookSG. ↩

-

A look at our young industrial workers. (1974, May–June). In Our Home (p. 15). Singapore: Housing and Development Board; Singapore. Department of Statistics. (1973). Report on the household expenditure survey 1972/1973 (p. 8). Singapore: Dept. of Statistics. (Call no.: RCLOS 339.41095957 SIN) ↩

-

Our Home, Jul 1972, p. 14; Our Home says farewell. (1989, August 31). The Straits Times, p. 23. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Make life easier with Sanyo home appliances. (1973, January–February). In Our Home (p. 30). Singapore: Housing and Development Board. ↩

-

SONY Home Entertainment. (1972, December). In Our Home (Back cover). Singapore: Housing and Development Board. ↩

-

Chow, W.F. (1989, July 19). Newsletters to fill residents in. The New Paper, p. 3. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩