The Stuff of Dreams: Singapore’s Early Print Ads

Before the advent of the internet, print advertisements reigned supreme. These primary documents provide important clues to the social history of the period as Chung Sang Hong tells us.

Advertising has existed since ancient times in various different shapes and forms. In the ruins of Pompeii for instance, advertisements hawking the services of prostitutes were carved into the buried stonework of this thriving Roman city before it was destroyed in 79 CE.1 In medieval Europe, town criers roamed the streets making public announcements accompanied by the ringing of a hand bell. In China, one of the earliest advertising artefacts discovered was a printing block of an advertisement for a needle shop in Jinan, Shandong province, dating from the Northern Song Dynasty (960–1127 CE).2

In various towns and cities across Asia, street vendors calling out to customers have existed since time immemorial. Itinerant hawkers – who moved from place to place peddling food, drinks, vegetables, textiles and various sundries while verbally “advertising” their wares – were once a common sight on the streets of Singapore.3

In the West, Johannes Gutenberg’s invention of the printing press around 1450 gave birth to print advertising as an unintended by-product, with the first printed advertisement in the English language appearing in 1477.4 By the 17th century, many European towns and cities were producing publications containing news that resembled modern newspapers.5

The revenue earned from advertising has always been a major source of profit for newspapers. Ever since newspapers first made their appearance, and for many centuries thereafter, this format became the main medium for advertisements. Indeed, some newspapers even had the word “Advertiser” boldly proclaimed on their mastheads. In Singapore, we had The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, which was first published in 1835.

From the publication of the island’s first local broadsheet, Singapore Chronicle and Commercial Register, in January 1824 to the outbreak of World War II in 1942, more than 150 newspapers had been published in various languages in Singapore.6 Judging from the large volume of advertisements in this medium, one can conclude that before the Japanese Occupation, the newspaper was the most important advertising platform in Singapore.

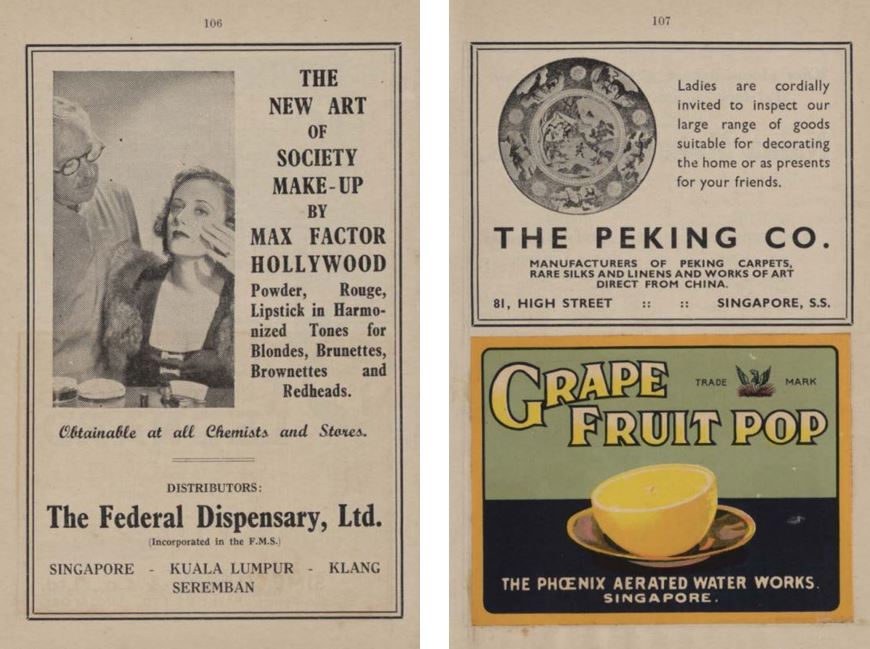

Of course, other print publications existed too, competing with newspapers for a slice of the advertising pie. Business directories, periodicals and magazines, souvenir publications, travel guides and related ephemera, and even cookbooks, contained advertisements, promoting various products and services that targeted specific audiences.

Apart from print media, other forms of advertising – advertisements screened before the start of movies, painted billboards, street posters, advertisements on buses and railway platforms, neon signs, etc – also existed in pre-war Singapore.

A Rich Advertising Heritage

Singapore has a rich advertising heritage that dates as far back as the early 20th century. This should come as little surprise, given the island’s history as a major entrepot port and commercial hub of the British Empire in Asia since its founding in 1819.

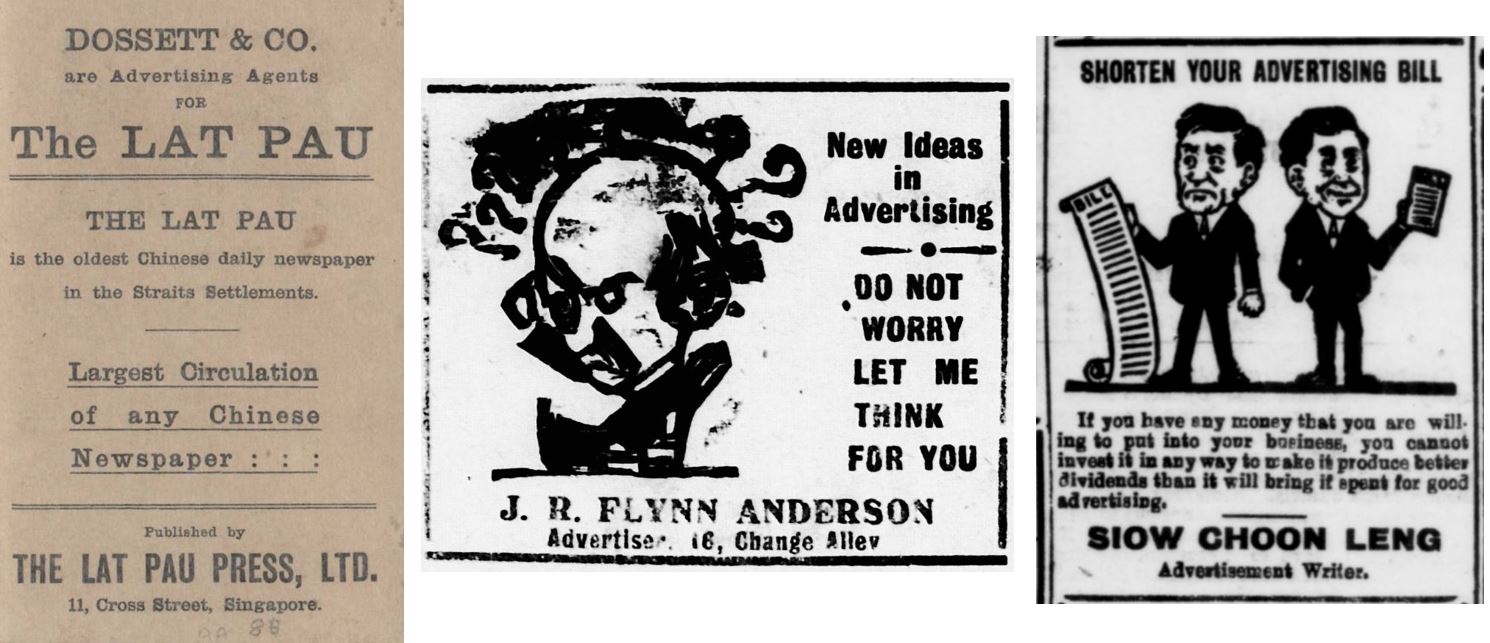

The first advertisements placed by advertising agents in Singapore appeared around the 1910s. In the Who’s Who in Malaya published in 1918, publisher Dossett & Co. promoted itself as the ad agent for the major local Chinese paper, Lat Pau.7 In return for a fee, ad agents helped clients create and place advertisements in newspapers – a service likely welcomed by European merchants who were eager to market their products to the large Chinese community in Singapore.

Similar advertisements were produced by J.R. Flynn Anderson, an “advertiser” who offered “new ideas in advertising”8 and “Advertisement Writer” Siow Choon Leng, who claimed that investing in good advertising would yield significant rewards for businesses.9

Singapore’s thriving advertising business before World War II was dominated by a few prominent ad agencies headed by Europeans, some of which were regional firms with headquarters in Hong Kong or Shanghai. There were at least 20 such firms specialising in advertising, publicity and marketing in Singapore and Malaya at the time.10

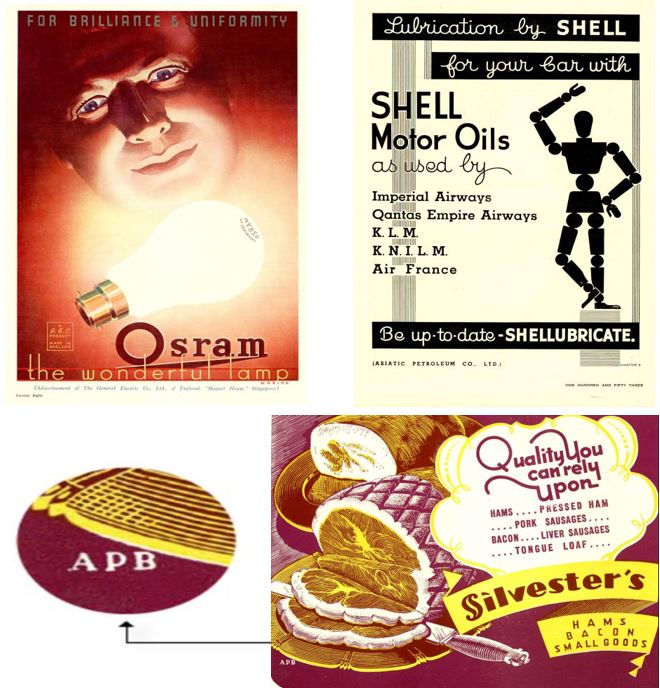

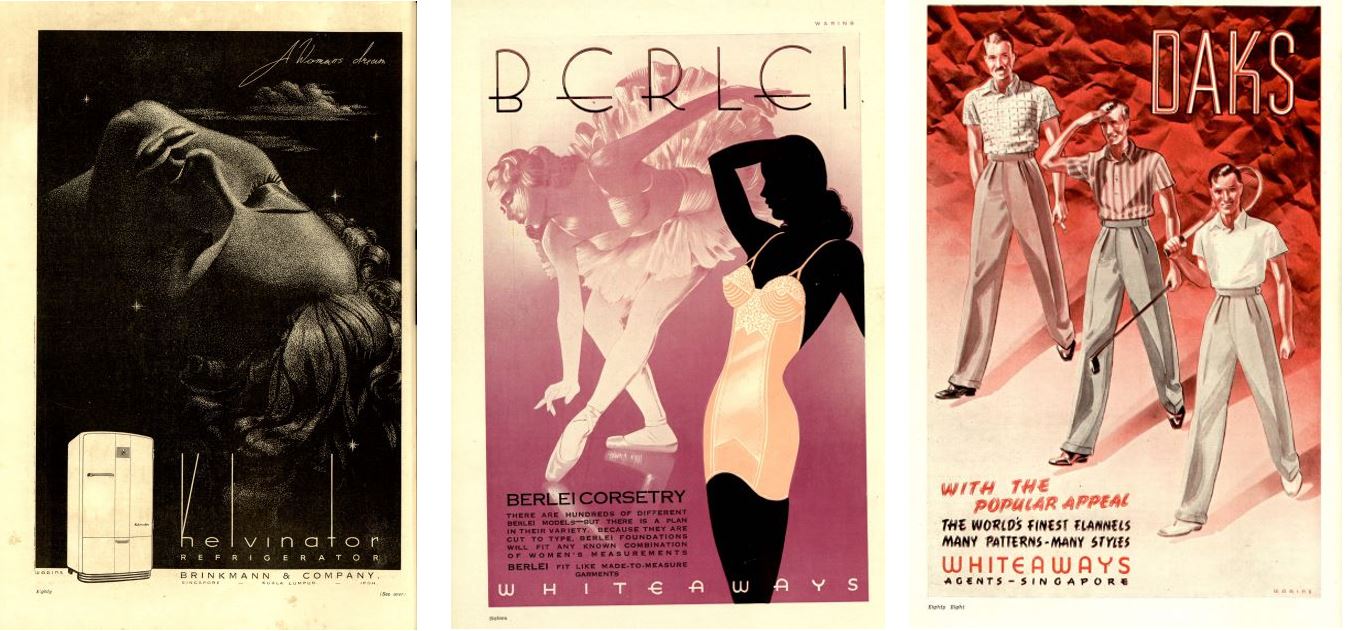

Most of these agencies were set up between the late 1920s and 30s. Some of them actively advertised their services in magazines and periodicals targeted at the business community. It was a common practice then for ad agencies to “sign off” advertisements they produced with the company’s name or initials: “signatures” such as “Master’s” (Masters Ltd), “Warins” (Warin Publicity Services Ltd) and “APB” (The Advertising & Publicity Bureau Ltd) would often be inserted unobtrusively into the advertisements. These traces left by pioneering agencies serve as clues that aid historians in their study of Singapore’s early advertising scene and its key players.

The booming market and demand for advertising in major Asian cities in turn fuelled the business of some of these early agencies. The Advertising & Publicity Bureau (APB) was the first regional agency to set up shop in Singapore in 1931. It was established in Hong Kong in 1922 by Englishwoman Beatrice Thompson to serve the advertising needs of its British and American clients in Asia.11 By 1940, APB was servicing many household brands and prominent firms, claiming to be the “largest advertising agency in the Far East”.12

Millington Ltd – one of the “Big Four” advertising agencies in Shanghai and founded by Briton F.C. Millington in 1920s – set up its Singapore branch in 1937 after having established a Hong Kong office earlier.13 There were also agencies started in Singapore that later became well known, one of which was Masters Ltd, founded in 1928 by Australian-born Ernst George Mozar, whose works can often be seen in early publications.

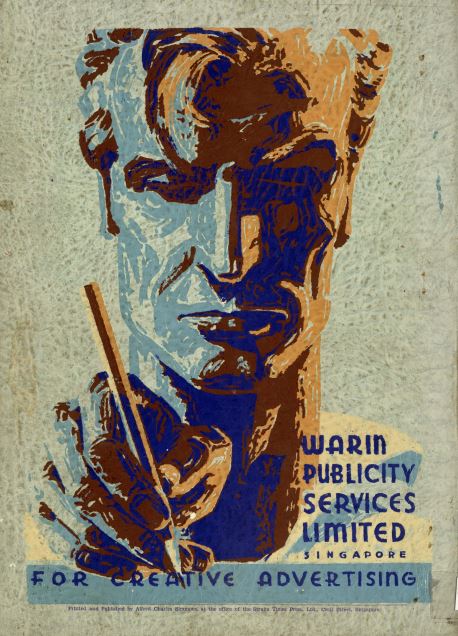

Warin Publicity Services: The First Local Agency

Among the first homegrown ad agencies in Singapore, one stood out for its vibrant and attractive print advertisements. The name “Warins” typically appears at the corner of many beautifully illustrated advertisements found in premium publications such as the 1930s issues of The Straits Times Annual, a periodical on Malayan and Singaporean life and culture, published by Straits Times Press between 1905 and 1982.

Warin Publicity Services was founded by Briton William Joseph Warin.14 W.J. Warin first arrived in Malaya in 1915 as a rubber planter.15 After his plantation business was hit by the Great Depression, Warin reinvented himself as a commercial artist and set up his advertising firm, Warin Studios, in a room on Orchard Road in 1932.16 His business flourished and within a span of three years, Warin Studios had moved into an office in the prestigious Union Building with a sizeable number of staff. The company also harboured ambitions of starting a branch in Hong Kong.17

Warin Studios was renamed Warin Publicity Services in 1937, and counted among its clientele major corporations and import houses in Singapore and Malaya as well as associates in London and New York.18 The agency’s success was largely due to the consistently high-quality and creative works it produced.19 Warin recruited professional talents from overseas, among whom was the Russian-born artist Vladimir Tretchikoff, who later found international fame for his painting Chinese Girl.20

Before relocating to Singapore, Tretchikoff had been a successful commercial artist in Shanghai working for Mercury Press, a prominent publisher of an English newspaper.21 Many of Warin’s eye-catching advertisements – inspired by the Art Deco movement – were designed by Tretchikoff.

The Chinese Influence

With the pre-war advertising scene dominated by Western expatriates, Chinese ad practitioners carved a name for themselves by serving the advertising needs of Chinese-speaking clients. Some were fine arts painters who practised commercial art on the side by creating artworks for advertisements. One of these was the prominent Chinese artist Zhang Ruqi (张汝器), who trained in Shanghai and France, and moved to Singapore in 1927. Renowned for his comic art and caricatures, Zhang founded a commercial art studio and created illustrations for advertisements such as Tiger Balm.22

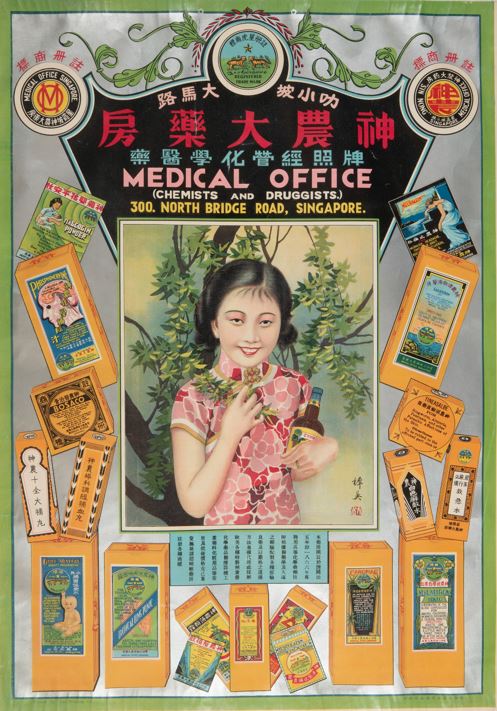

Local Chinese printers also produced advertisements in the distinctive “picture calendar” (yue fen pai; 月份 牌) style which originated in Shanghai. These featured beautiful women dressed in form-fitting cheongsam (or qipao), Western attire and even swimsuits, and were highly popular in China and in overseas Chinese communities, including Singapore.

(3) Whiteaways department store advertising the Daks brand of flannels that were available in “many patterns many styles”. Image reproduced from The Straits Times Annual, 1940, p. 88.

Post-war Developments

With the outbreak of World War II, the business of most ad agencies came to a grinding halt. Many advertising practitioners resumed their trade after the Japanese Occupation ended in September 1945. Newcomers entered the scene in search of opportunities as Malaya returned to British rule.

Still, the post-war advertising industry was dominated by firms with links to Britain, Australia, the United States and Hong Kong, with expatriates mostly holding the key positions. In 1948, Singapore’s first advertising association, Association of Accredited Advertising Agents of Malaya (4As), was formed to safeguard stakeholders’ interests and raise the standards of the local advertising industry. Its three founding members – Masters Ltd, Millington Ltd and Messrs C.F. Young – were key players who had been active before the war.23

The post-war era also saw the penetration of international advertising firms into the Asian market who successfully tied up with local agencies as partners. In the 1950s, Masters Ltd partnered leading London agency, S.H. Benson, to grow its business, eventually becoming S.H. Benson (Singapore) in 1961 with offices in Kuala Lumpur and Hong Kong. The company subsequently merged with Ogilvy & Mather and became Ogilvy, Benson & Mather in 1971, making Masters the first Singapore agency to have evolved into an international agency.24

C.F. Young had been a manager at the aforementioned APB before the war. In 1946, he started his own firm, C.F. Young Publicity, which was later renamed Young Advertising and Marketing Ltd to serve local and overseas clients. It was eventually acquired by a British company, London Press Exchange, in 1966 and was renamed LPE Singapore Ltd.25

Another foreign agency, Cathay Advertising Limited, seemed to have followed a similar trajectory. Its founder, Australian businesswoman Elma Kelly, went to Shanghai in the early 1930s to work for Millington Ltd. She was posted to Hong Kong to manage the agency’s branch office in 1935 but ended up in internment when the city fell to the Japanese in 1941.

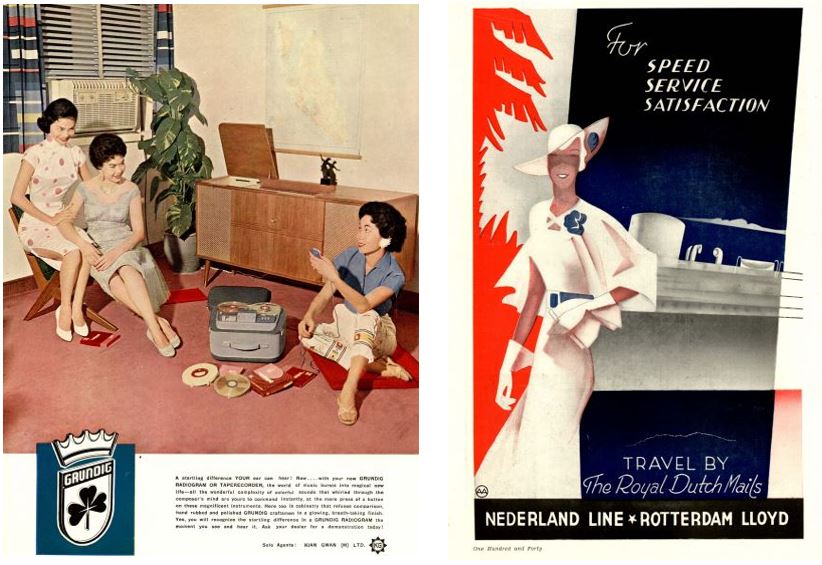

(Right) This advertisement by The Royal Dutch Mails evoked the modernity and glamour associated with luxury cruise liners. Image reproduced from The Straits Times Annual, 1937, p. 140.

After the war, Kelly and a few former Millington staff started Cathay Advertising in Hong Kong. Its Singapore office opened in 1946, and branches were subsequently set up in Kuala Lumpur and Bangkok. In 1963, Cathay was reported to be one of the three largest ad agencies in Singapore.26 It later merged with leading Australian agency George Patterson Pte Ltd and was eventually acquired by Ted Bates & Co (now Bates Worldwide)27, a New York-based advertising giant that expanded into Southeast Asia in the late 1960s.

The Stuff of Dreams

The intended audience of early print publications is quite different from the masses that similar media can reach today. Before the 1950s, as a result of low literacy rates and income levels, the ability to read and the means to purchase reading materials was the privilege of the minority.28 In colonial Singapore, these would be the Europeans as well as the wealthy and better-educated members of local communities. Invariably, most of the advertisements featured in early print publications were targeted at the upper crust of society, reflecting their lifestyles, tastes, preferences, values and outlook on life.

Given Singapore’s rich advertising history, it is surprising that precious little research has been done on the subject, even though a large collection of primary source materials exists. Through a new exhibition, “Selling Dreams: Early Advertising in Singapore”, the National Library aims to uncover the fascinating history of this business and the untold stories behind some of the earliest iconic ads that appeared in print.

With the passage of time, the products and services found in these vintage advertisements and also the manner in which they were touted to the general public may have become antiquated or even obsolete. However, early print advertisements still remain valuable as primary historical documents that can provide important clues to the lifestyle, culture, business and social histories of the period. Many of these old advertisements still strike a chord with people today by virtue of the sentiments they reflected – the values, aspirations, desires and hopes – and also perhaps fears – of the readers and producers of advertisements at a particular point in our history.

Apart from marketing products and services, early advertising adopted the strategy of selling a “dream” – a desirable outcome, tangible or intangible, to its intended audience, and closely associated with purchasing the advertised product or service. Such an advertising tactic is only too familiar to modern-day consumers who are often lured into parting with their money – whether on fast cars and jewellery or common everyday items like detergent and toothpaste – by slick advertisements promising them instant gratification.

The product range as well as the scale and size of the advertising industry and its platforms may have changed drastically over the years, but the one constant that has survived to this day is the aspect of selling the stuff that is of dreams.

ABOUT THE EXHIBITION

“Selling Dreams: Early Advertising in Singapore” opens on 20 July 2018 at the gallery on level 10 of the National Library Building on Victoria Street. Inspired by the concept of a department store, the exhibition contains nine “departments” showcasing various advertisements for food, medicine, household goods, automobiles, travel services, hospitality facilities, entertainment, fashion and retail.

The exhibition will present a variety of print publications from the 1830s to 1960s that are rich in advertising content and drawn from the National Library’s collections, including copies of the first local newspaper, Singapore Chronicle and Commercial Register, from 1833. The earliest advertisements in newspapers were primarily shipping and commercial notices targeted at the mercantile community, along with advertisements of imported goods, services and recreational activities.

Early business directories, periodicals, magazines, souvenir publications, travel guides, and ephemera such as posters and flyers are also rich sources of advertising material. Print advertising reigned supreme in Singapore until television made its foray here in 1963. The new media revolutionised the dissemination of information and entertainment, and as TV sets became increasingly common in local households, advertisements on television became the game changer in the industry.

A book titled Between the Lines: Early Print Advertising in Singapore 1830s–1960s will be launched in conjunction with the exhibition, and sold at major bookshops in Singapore as well as online stores. A series of programmes has been organised too, including guided tours by curators and public talks.

Chung Sang Hong is Assistant Director (Exhibitions & Curation) at the National Library, Singapore. He is the lead curator of the “Anatomy of a Free Mind: Tan Swie Hian’s Notebooks and Creations” exhibition.

Chung Sang Hong is Assistant Director (Exhibitions & Curation) at the National Library, Singapore. He is the lead curator of the “Anatomy of a Free Mind: Tan Swie Hian’s Notebooks and Creations” exhibition.

NOTES

-

Fletcher, W. (2010). Advertising: A very short introduction (p. 31). Oxford: Oxford University Press, New York. Retrieved from OceanofPDF.com ↩

-

许俊基. (主编) [Xu, J.] (Ed.). (2006). 中国广告史 [Zhongguo guang gao shi] (p. 70). 北京: 中国传媒大学出版社. (Call no.: Chinese RBUS q659.10951 ZGG) ↩

-

Romance of Advertising. (1935, October). The RODA: Magazine of the [Rotary] clubs of Malaya and Siam, 5 (52),199–203. Singapore: Roda. (Call no.: RRARE 369.509595 R; Microfilm no.: NL 7312) ↩

-

Fletcher, 2010, p. 31. [Note: The advertisement was issued by English printer William Caxton and offered for sale his edition of the Sarum Ordinal, a manual for priests.]. ↩

-

Williams, K. (2010). Read all about it!: A history of the British newspaper (pp. 39–40)). London; Routledge, New York. (Call no.: R 072.09 WIL) ↩

-

[1] Lim, P.P.H. (1992). Singapore, Malaysian and Brunei newspapers: An international union list (pp. 3–56). Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. (Call no.: RSING 016.0795957 LIM-[LIB]) ↩

-

Dossett, J.W. (1918). Who’s who in Malaya, 1918 (p. 137). Singapore: Printed for Dossett & Co. by Methodist Pub. House. (Call no.: RRARE 920.9595 WHO; Microfilm no.: NL 5829) ↩

-

Page 2 Advertisements Column 1. (1918, December 11). The Singapore Free Press, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Page 3 Advertisements Column 3. (1919, March 4). The Straits Times, p. 3. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Advertisers Association. (1971). A review of advertising in Singapore and Malaysia during early times (p. 26). Singapore: Federal Publications. (Call no.: RSING 659.109 ADV) ↩

-

Notices. (1931, January 16). The Singapore Free Press, p. 9. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Page 16 Advertisements Column 1. (1940, January 2). The Straits Times, p. 16. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Advertising man arrives. (1937, December 8). The Straits Times, p. 12. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Who’s who in Malaya, 1939: A biographical record of prominent members of Malaya’s community in official, professional and commercial circles (p. 139). (1939). Singapore: Fishers Ltd. (Call no.: RCLOS 920.9595 WHO-[RFL]; W.J. Warin dies in Singapore. (1950, June 11). The Straits Times, p. 9. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Who’s who in Malaya, 1939, p. 139. ↩

-

Mainly about Malayans. (1938, December 4). The Straits Times, p. 7. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Warin Studios. (1935, September 4). The Singapore Free Press, p. 6. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The rise of Warin Studios: All forms of publicity. (1937, April 27). The Singapore Free Press, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The RODA: Magazine of the [Rotary] clubs of Malaya and Siam, Oct 1935, pp. 199–203. ↩

-

Goerlik, B. (2013).Incredible Tretchikoff: Life of an artist and adventurer (p. 152). London: Art/Books. (Call no.: RART 759.968 GOR). [Note: Chinese Girl, popularly known as The Green Lady, portrays a young Chinese woman with a blue-green face and dressed in traditional Chinese costume. It sold for almost £1 million at an auction in London in 2013.]. ↩

-

姚梦桐 [ Yao, M.]. (2017). 流动迁移·在地经历: 新加坡视觉艺术现象 (1886–1945) [Liu dong qian yi zai di jing li: Xinjiapo shi jue yi shu xian xiang (1886–1945)] (p. 136). 新加坡: 南洋理工大学孔子学院. (Call no.: Chinese RSING 709.5957 YMT) ↩

-

Advertisers Association, 1971, p. 26. ↩

-

Ling, P. (2017). Advertising in Singapore: Regional hub, global model. In R. Crawford, L. Brennan & L. Parker (Eds.). Global advertising practice in a borderless world (pp. 176–177). New York: Routledge. (Call no.: RBUS 659.1 GLO) ↩

-

Malayan Advertisers Association. (1963, May). Newsletter, 2 (3), p. 2. Singapore: Malayan Advertisers Association. Available via PublicationSG. ↩

-

Kuo, E.C.Y. (1980). The sociolinguistic situation in Singapore: Unity in diversity. In E.A. Afendras & E.C.Y. Kuo (Eds.), Language and society in Singapore (p. 53). Singapore: Singapore University Press. (Call no.: RSING 409.5957 LAN); Tan, L.G. (2014). Charting multilingualism in Singapore: From the nineteenth century to the present [Final Year Project] (pp. 24–25). Retrieved from Nanyang Technological University website. ↩