Five Ashore in Singapore: A European Spy Film

Raphaël Millet sits through a B-grade movie dismissed by critics as belonging to the genre of Eurospy flicks that parody James Bond – and discovers a slice of Singaporean celluloid history.

Few foreign films, especially Western ones, have ever been shot completely on location in Singapore. In the latter half of the 1960s, a handful of low-budget commercial European films – or B-grade movies, to borrow a term from the film industry – were produced with the Lion City as an exotic backdrop. These “Eurospy films”, a variation of the broader “super spy” genre, were obvious rip-offs of the James Bond series by Ian Fleming and were especially popular in Germany, Italy, France and Spain. When the first Bond movie Dr No was released in 1962, it was swiftly followed up by a string of copycat European films based on Secret Agent 007.

The “super spy” craze peaked between 1966 and 1968 and included a few shot-in-Singapore films like So Darling So Deadly (1966),1 Suicide Mission to Singapore (1966)2 and Five Ashore in Singapore (1967). Apart from rare mentions in articles or books,3 precious little has been written about these films, even though they all captured Singapore at a time of change in the first few months or years following its independence in 1965. Of these three films, the most outstanding is Five Ashore in Singapore.

OSS 117, the “French Bond”

Five Ashore in Singapore (see text box below) was a French-Italian collaboration between producers Pierre Kalfon and Georges Chappedelaine of Les Films Number One in Paris, and Franco Riganti and Antonio Cervi of Franco Riganti Productions in Rome. The international distribution of the film was handled by Rank Organisation, a British conglomerate created in the late 1930s.

Two versions of the film were produced simultaneously: one in English and the other in French, which is why the producers took pains to cast as many actors as possible who were bilingual so that they could play their parts in both languages. Only the few main actors who were not conversant in French had to be dubbed along with all the Singaporean extras.

Based on the 1959 novel Cinq gars pour Singapour by the prolific French writer Jean Bruce (1921–63), the film was initially titled OSS 117 Goes to Singapore after the spy novel series, OSS 117, which Bruce created in 1949. The story centres around the secret agent Hubert Bonnisseur de la Bath, who worked for the Office of Strategic Services, or OSS, during World War II. Like his spy novelist counterpart Ian Fleming, Bruce set his adventures in cities such as Tokyo, Bangkok, Caracas and Istanbul for the “exoticism” these places evoked in the minds of Western audiences. Naturally, Singapore was selected as the setting for Five Ashore in Singapore.

In real-life, the code number 117 was assigned to William L. Langer, chief of the OSS Research and Analysis Branch whom Bruce had reportedly met during World War II when the latter was involved with the French Resistance. Interestingly, while OSS 117 has been called the “French Bond” after the famous British Secret Service agent, Bruce’s French agent actually pre-dates James Bond by four years (Ian Fleming’s first Bond novel Casino Royale was published only in 1953). Furthermore, the archetypal three-digit code name 117 existed long before Fleming decided to call his character Agent 007.4

Even the silver screen adaptation of OSS 117 precedes James Bond: the French language OSS 117 n’est pas mort (OSS 117 Is Not Dead) was produced in 1956 and commercially released in 1957.

On the other hand, Dr No, the first James Bond film, was produced in 1962. In the 1960s, the OSS 117 character was again featured in a successful Eurospy film series directed by French filmmakers André Hunebelle (in 1963, 1964, 1965 and 1968) and by Michel Boisrond (in 1966). On these occasions, the lead role was played initially by American Kerwin Mathews, and subsequently by Frederick Stafford.5

OSS 117 Becomes Art Smith in Singapore

It is within the context of the successful Eurospy craze that French producer Pierre Kalfon offered director Bernard Toublanc-Michel the chance to adapt another OSS 117 story, Cinq gars pour Singapour. Due to copyright issues, unresolvable because Jean Bruce had died a few years earlier, neither the character Hubert Bonnisseur de la Bath nor his codename OSS 117 could be used in the film.

Hence in the movie, the hero is renamed Art Smith. A clear playful allusion is nevertheless made at the beginning of the movie when a car waiting for him at Singapore’s old Paya Lebar Airport is numbered 117.

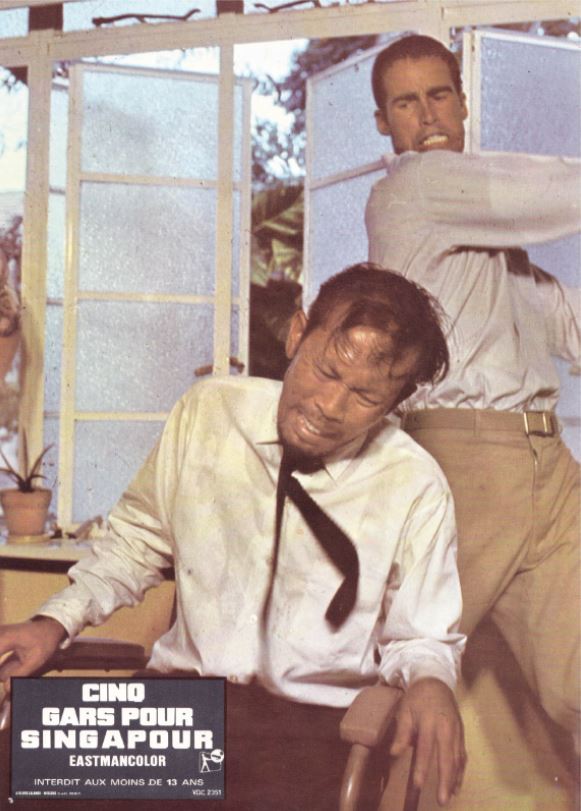

Five Ashore in Singapore, like so many similar B-flicks, has a very simple plot that closely follows that of the original novel. Captain Art Smith of the Central Intelligence Agency is sent to Singapore to investigate the whereabouts of several US Marines who mysteriously disappear while on shore leave. Upon his arrival, Smith meets four Marines who volunteer to assist him. Together, the five men pretend to be a group of Marines looking for a good time, but in fact hoping to be caught in the same trap as their missing colleagues.

Their search takes them all around Singapore, and eventually leads them to a mad scientist who has apparently kidnapped the marines for a diabolical experiment. This lame twist in the film’s finale is typical of super spy stories: however credible as a narrative, they generally end on a weak and often implausible note. Nevertheless, what makes Five Ashore in Singapore particularly noteworthy is its value as a documentary that captures realistic scenes of 1960s Singapore.

From R&R to I&I

Following the end of World War II, the US military used Singapore’s facilities for the repair and refuelling of its ships and aircraft, and also as a “shore leave” destination for troops stationed in various conflict zones throughout Asia.

In addition, on the orders of US President Harry Truman, from as early as July 1950, hundreds of American military “advisers” accompanied a flow of American tanks, planes, artillery and other aid supplies to the French forces in Vietnam embroiled in the first Indochina War.6 Many of these military personnel, inbound or outbound of Vietnam, transited at one time or another in Singapore.

By the time director Bernard Toublanc-Michel adapted Bruce’s novel into a movie in 1966, American involvement in Vietnam had dramatically escalated, with active combat units joining the fray in 1965 onwards to wage war against the communist forces of the north. This development impacted Singapore directly as demand grew for a Rest & Recuperation (R&R) programme for American troops. All active US military personnel serving in Vietnam were eligible for a five-day R&R during their tour of duty – after 13 months in the case of Marines, and 12 months for soldiers, sailors and airmen – in places such as Singapore, Hong Kong, Kuala Lumpur, Penang, Manila, Seoul, Taipei and Tokyo.

Soldiers nicknamed these breaks “I&I”, or “Intoxication and Intercourse”, as these outings were invariably fuelled by plenty of alcohol, drugs and sex. Singapore, true to its form then, was depicted as a rather seedy and dangerous city in publicity materials that were issued when Cinq gars pour Singapour was released in France in March 1967. The press release took pains to highlight the fact that American Marines are routinely warned to behave with discretion when they are in Singapore for R&R, including dressing as civilians when travelling in the city, because there has been cases where local boys had tried to pick a fight.7

In an interview given at his apartment near Paris on 1 June 2018, Toublanc-Michel said that the geopolitical context of Singapore against the backdrop of the Vietnam War was what made the adaptation of Bruce’s OSS 117 novel Cinq gars pour Singapour so interesting to him: it gave him the opportunity to explore and expose what he calls “les à-côtés de la guerre” (“extra income and activities”) that was generated on the sidelines of the war.8

In this sense, Bruce’s novel and its film adaptation by Toublanc-Michel also pre-date Paul Theroux’s 1973 novel Saint Jack and its subsequent 1979 film adaptation by Peter Bogdanovich depicting American soldiers in Singapore on R&R during the Vietnam War and the pimps who provide them with the necessary “entertainment”.9

Direct mention of the Vietnam War is made in Five Ashore in Singapore when the Marines led by Captain Art Smith take refuge in a movie theatre, where a newsreel in Malay addressing the Vietnam conflict and showing images of North Vietnamese troops is screened. Real American vessels are also seen anchored in the Singapore Strait – Pierre Kalfon had managed to obtain from the US military a permit to film these scenes, much to Toublanc-Michel’s delight10 – a rare visual testament of US naval power in Singapore waters at the time.

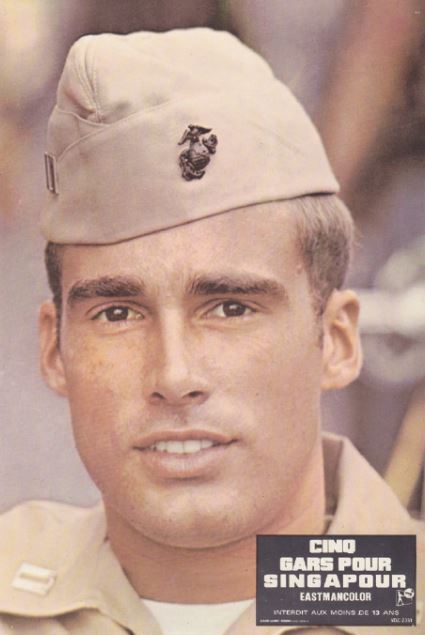

The background setting of the Vietnam War is made even more significant by the fact that the lead character Art Smith is played by Sean Flynn, son of legendary Hollywood actor Errol Flynn (and Hollywood-based French actress Lili Damita). The younger Flynn was taking a break from his photojournalism stint in Vietnam, where he had arrived in January 1966 as a freelance photo-reporter, working occasionally for magazines like Paris Match, Time, Life and the Daily Telegraph. Flynn quickly made a name for himself and earned the reputation of being a high-octane risk-taking photojournalist along the likes of British photographer Tim Page and American photojournalist Dana Stone, both of whom Flynn had befriended in Vietnam.

As freelance photojournalism did not pay well, Flynn went back to acting – something he had done from time to time since his teen years – to earn a fast buck. As Flynn had been in Vietnam and witnessed real action there, his sheer presence lent the film an added layer of authenticity.11 As it turned out, Five Ashore was to be Flynn’s last screen appearance before he returned to Vietnam to cover the war. He mysteriously disappeared in the spring of 1970 near the frontier between Cambodia and Vietnam, never to be found again. Flynn’s mother would reluctantly declare him dead in absentia in 1984.

Singapore in the Summer of 1966

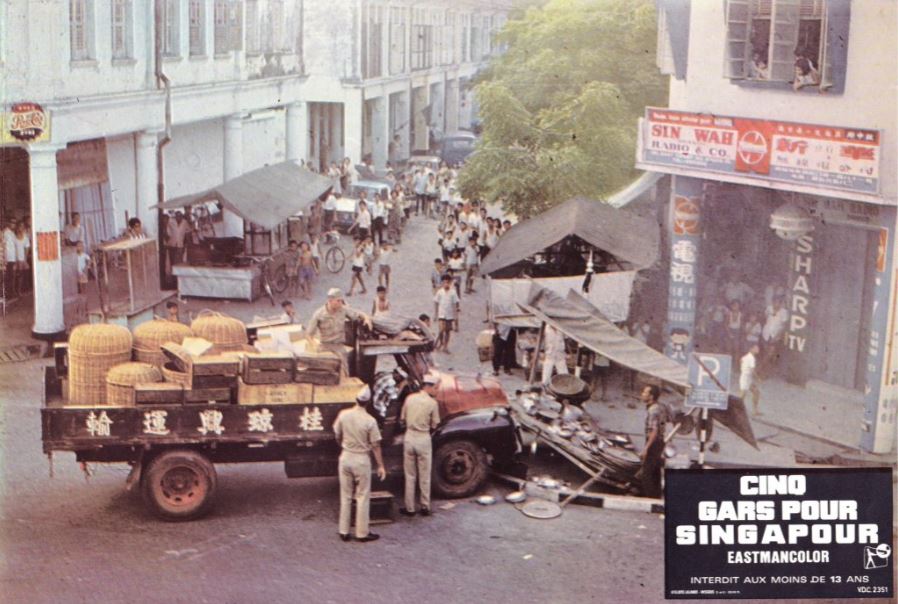

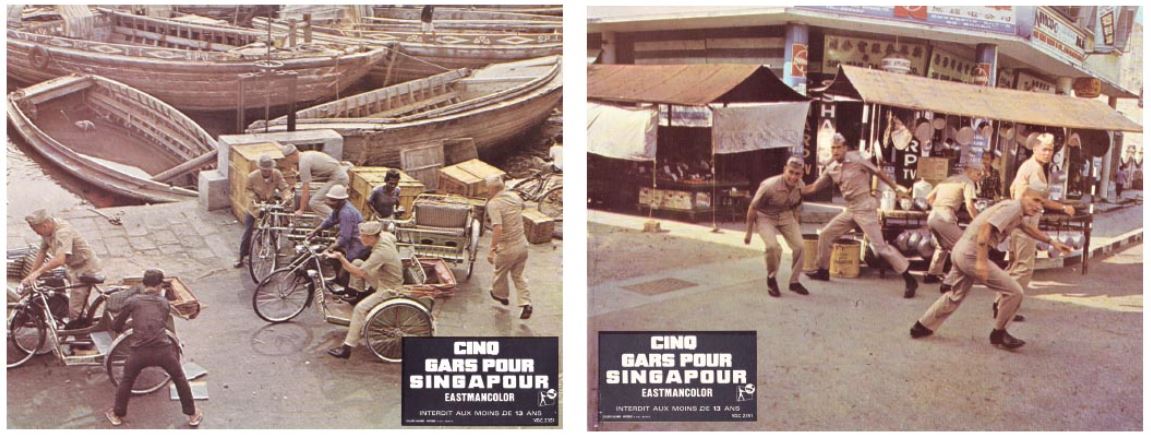

Five Ashore in Singapore was filmed on Eastmancolor, a colour film technology introduced in 1950, and shot entirely on location in Singapore between August and October 1966. When Bernard Toublanc-Michel was first approached by producer Pierre Kalfon to direct the screen adaptation of Bruce’s book, he had insisted that the entire film be shot on location in Singapore.12

The rest is history: a total of 52 locations were used in the film,13 such as the Cathay Hotel (where Captain Art Smith stays), Change Alley, Clifford Pier, the Majestic Theatre at Eu Tong Sen Street, the old Paya Lebar Airport, Boat Quay, Telok Blangah, Keppel Golf Club and some very rare footage of the long-gone Kampong Telok Saga on Pulau Brani. This tour of the Lion City allows viewers today to travel back in time to 1966 “… wishing … [they] were in the company of less brutal, more appreciative tourists“14 than this wild bunch of hard-drinking and brawling Marines.

The story begins on 5 August 1966, as indicated in the visa stamped on Art Smith’s passport on his arrival in Singapore. It was just a few days before the fledgling republic celebrated its first National Day on 9 August, a week-long calendar of festivities that included a parade, fireworks displays and cultural shows. In the film, numerous glimpses of the national flag can be seen on the streets and on buildings, as well as billboards and banners with the words “Majulah Singapura”, which had been officially adopted as Singapore’s national anthem in 1965.

Having assisted New Wave film luminaries such as Agnès Varda and Jean-Luc Godard in their work, Toublanc-Michel was very familiar with portable film equipment that required little or no set-up time. Thus, he was ready to shoot nearly anywhere and at any time in Singapore, using two handheld cameras operated by director of photography Jean Charvein and cameraman Jean-Marc Ripert.15

In this way Toublanc-Michel was able to inject a documentary-like feel to his film, a characteristic captured by the numerous seemingly “stolen shots” of the city – of people and places caught unawares, something he remains particularly proud of.16 With its tight budget, Five Ashore in Singapore could not afford to have entire streets or plazas cordoned off, nor could it hire dozens of extras.

To prepare for the scenes, Toublanc-Michel had his actors rehearse beforehand in the courtyard of the Cathay-Keris Studio on East Coast Road or at the Ocean Park Hotel next door where they were staying. Following the rehearsal, he would take his actors to the film location in a taxi, and have them wait while he discreetly positioned his two cameramen. The actors would emerge from the waiting taxi only when the director beckoned to them, walking into the scene to play their parts extemporaneously amidst whoever was present.17 In this way, real passers-by were filmed watching the film being shot and unwittingly became part of a scene.

For Western audiences, one of the main draws of the film was to view the “real” Singapore with their own eyes. Instead of the typical backwater Asian city that they had expected to see, the audience was surprised to find a unique place burgeoning with “impressive buildings, luxury shops, grand hotels and traffic jams”,18 a place where the East and the West meet, to use a cliché.

To add a frisson of tension to the film, press materials highlighted the simmering undercurrents and often prickly relationship between the races, making reference to Chinese, Malays and Indians who “cohabit, but do not sympathise, distrust each other and reciprocally accuse each other”.19 This specific reference could have been a nod to the bloody racial riots of 1964.

Singapore is also melodramatically described in the press release as an unsafe city to live in: “At night, Singapore is very vibrant and even dangerous. Vibrant because people live on the streets[…]. Dangerous because there are frequent quarrels. Men of all races and all horizons have disappeared in it without leaving a trace, or have been found in back alleys with their throats cut”.20 The disquieting backdrop serves as the perfect setting for the hammy cloak-and-dagger film plot.

An International Cast (and Some Locals)

The main cast of Five Ashore in Singapore was international, with actors chosen not only for their good looks and talent, but also for their fluency in both English and French. The film was shot in both languages to avoid unnecessary dubbing during post-production work. Pure action scenes mostly required just one take, while heavily dialogued scenes with close-ups required two takes: the first in English, the second in French.21 The two versions of the film are still in circulation today, and each presents a slightly different edit from the other.

Sean Flynn – in what would be his final and, in this writer’s opinion, his best role yet – plays Art Smith with such detached nonchalance that he lends his character a certain mix of sangfroid and casual insouciance that most latter-day OSS 117 and perhaps even some James Bond screen incarnations have never been able to replicate. The other main male roles of the Marines went to American Dennis Berry, who had grown up in the US and France;22 British middleweight boxer and former world champion Terry Downes; polyglot Franco-Swiss Marc Michel, who had recently gained fame for his part in Jacques Demy’s 1961 film Lola; and the well-travelled Frenchman Bernard Meusnier. To look like real American Marines, the actors were given a crew cut by the hairdresser of the US Embassy in Paris before they arrived in Singapore.

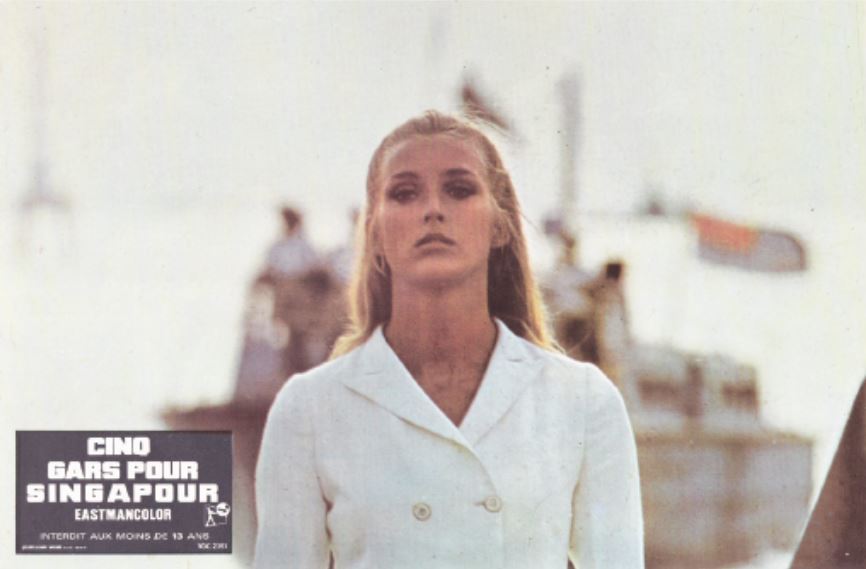

The main female lead went to Swedish-French model and actress Marika Green, who had recently gained fame for her role in Robert Bresson’s 1959 film, Pickpocket.23 With her shapely figure and requisite long legs, the actress was the perfect “Bond Girl”. All these performers were bilingual with the exception of Briton Terry Downes, whose lines had to be dubbed in French.

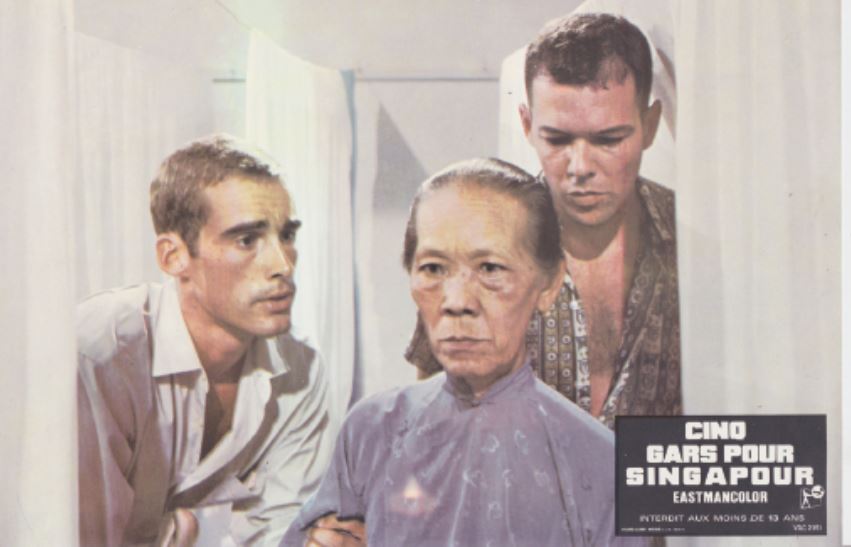

Several of the film’s key Asian supporting roles unfortunately followed in the tradition of “yellowface”, an early practice in the West (mostly on Broadway and in Hollywood) that saw Asian roles played by white actors. Hence, the mad scientist Ta Chouen was played by the Italian Andrea Aureli (credited by his Americanised stage name Andrew Ray); mama-san Tchin Saw by Trudy Connor; treacherous middleman Ten Sin, an improbable “Chinese” wearing a cap that resembles more a Muslim songkok, and played by Italian actor Jessy Greek (whose real name was Enzo Musumeci Greco); and odd-job man Kafir played by William Brix. All either wore terrible make-up, or appeared sans make-up, which only exaggerates the stereotyping to the point where one wonders if the yellowfacing was deliberate.

However, a couple of Singaporean talents did get a chance to act. For example, Ismail Boss24 played the role of a mean Malay thug who kidnaps the American Marines. He was described in the press materials as an amateur actor who had been talent spotted by the production team whilst they were recceing a Malay stilt village where he lived.

The female role of Tsi Houa was played by Chan See Foon (credited as “See Foon” without her surname in the film).25 Chan had been one of Singapore’s early supermodels. After having won the title of Varsity Queen in university, she began modelling and played occasional bit parts on TV and in film. In Five Ashore in Singapore, she has a full scene with Sean Flynn on Pulau Brani in which her baby is forcibly taken away from her before she dies in an explosion. A few other minor Asian roles were given to Singaporeans too, such as the part of local boys played by actors Abdullah Ramand and Lim Hong Chin.

The Singapore production manager G.S. Heng was a producer employed by Cathay-Keris for many years under the command of general manager Tom Hodge. Cathay had excellent shooting facilities at its Katong studio on East Coast Road, which was used by many overseas productions, including Five Ashore in Singapore for its nightclub and opium den scenes. Next to the studio was Ocean Park Hotel (also owned by Cathay Organisation), where the cast and crew were conveniently accommodated during the entire duration of the shoot, and where a party scene was filmed.

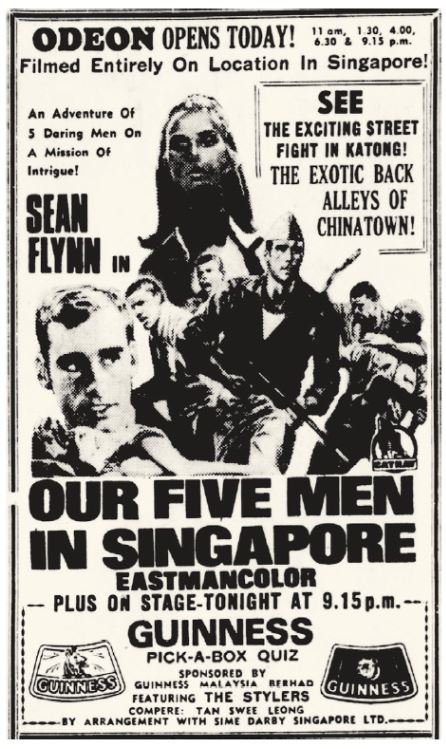

Today, Five Ashore in Singapore remains as a little-known but precious piece in the history of film in Singapore. Bringing together an international cast along with a few local actors, it captured the Lion City at a time of historic change. With its editing completed in January 1967, Five Ashore was commercially released in March 1967 in France – where it enjoyed a particularly long run at the Balzac Theatre in Paris – with a PG-13 rating. The film was subsequently released in Europe and North America where it was shown in cinemas right into the beginning of 1968.

As for Singapore, the film was retitled as Our Five Men in Singapore and opened on 17 February 1968 at the Odeon cinema on North Bridge Road. Advertisements enticed would-be patrons to catch the “exciting street fight in Katong” and “exotic back alleys of Chinatown”, and touted it as “filmed entirely on location in Singapore”. Perhaps this is the main reason why we should watch the film – regardless of the half-dozen titles it is known by – and recapture a slice of 1960s Singapore.

A MOVIE BY ANY OTHER NAME

Like similar B-movies of the era, the film went by several different titles. The English version in the United Kingdom was called Five Ashore in Singapore, and in the United States as the double-barrelled Singapore, Singapore.26 Inexplicably, in Singapore it was first announced as Singapore Mission for Five,27 before being eventually retitled and released as Our Five Men in Singapore in February 1968.

Its original title Cinq gars pour Singapour is French, as this is the title of the French novel it is adapted from. Cinq gars pour Singapour, when literally translated, means “Five guys for Singapore” – cinq is “five”, gars is “guys” and pour is “for” – and is a clever phonetic pun on the name of the city, since cinq-gars-pour (when said quickly) sounds exactly like “Singapour”.

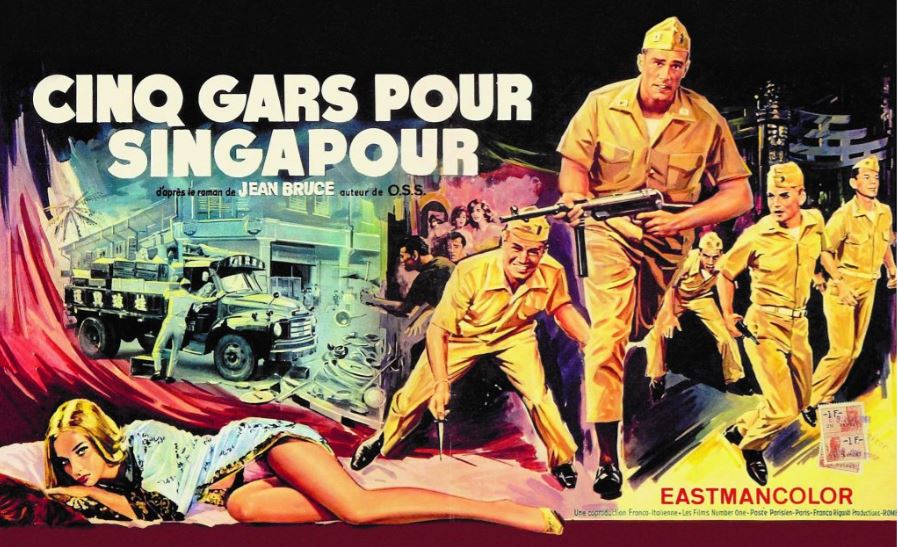

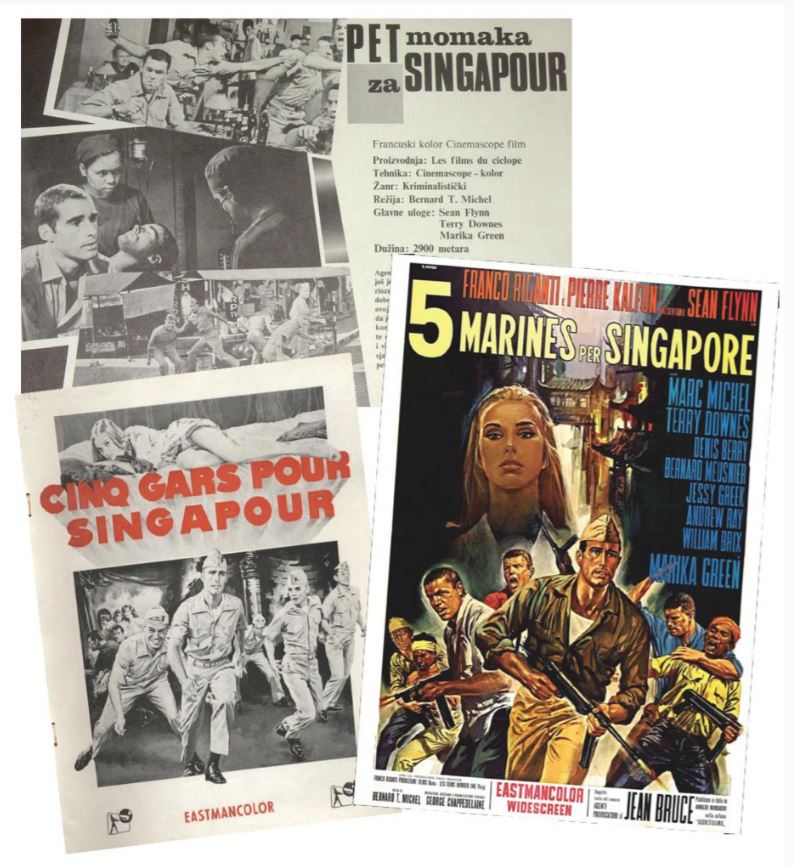

(Left) The French press kit of Five Ashore in Singapore. The film was commercially released in March 1967 in France, where it enjoyed a long run at the Balzac Theatre in Paris. Courtesy of Raphaël Millet.

(Right) The Italian film poster for Five Ashore in Singapore, 1967. Courtesy of Raphaël Millet.

The pun is lost in translation of course, but details such as the number of male protagonists and location were kept intact in most of the titles of the foreign-language versions that were either dubbed or subtitled, for example Cinco Marinos en Singapur in Spanish (also Cinco Muchachos en Singapur in Argentina), Cinque Marines per Singapore in Italian, Vijf Kerels Voor Singapore in Dutch, and Pet Momaka za Singapour in Serbian for the Yugoslavian version of the film.

The music for Five Ashore in Singapore was composed by renowned French composer Antoine Duhamel, who had just begun his career by scoring French New Wave films by legendary directors Jean-Luc Godard and François Truffaut. At the request of Five Ashore’s director Bernard Toublanc-Michel, he composed Somewhere in Singapore (also known as the Marines’ March – “La marche des Marines” in French) with lyrics by Jimmy Parramore.

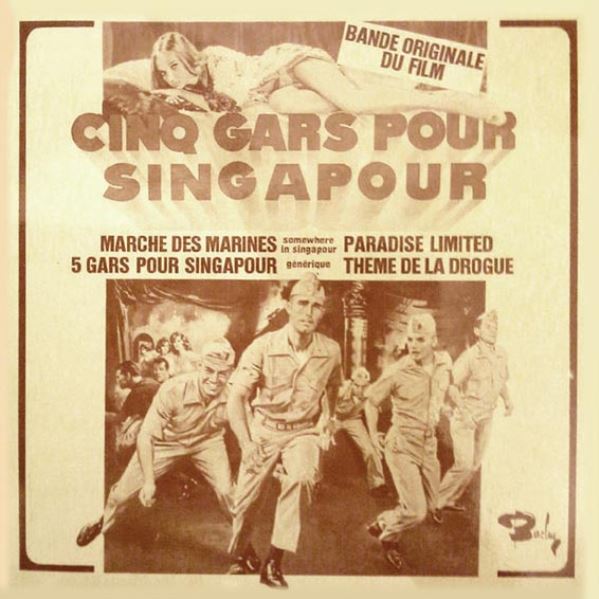

Cover of the French record album of Five Ashore in Singapore, 1967. The music for the film was composed by renowned French composer Antoine Duhamel. © Barclay Editions. Courtesy of Raphaël Millet.

Cover of the French record album of Five Ashore in Singapore, 1967. The music for the film was composed by renowned French composer Antoine Duhamel. © Barclay Editions. Courtesy of Raphaël Millet.

Quite brazenly, the song was directly based on the melody of the now iconic Yellow Submarine, the Beatles’ number one hit in 1966. Indeed, Toublanc-Michel had asked his actors who played the five Marines to stride out of Clifford Pier with the Beatles’ song playing in their heads, so as to lend a certain rhythm to their swagger.

Other melodies with no lyrics composed by Duhamel include Paradise Limited for the club scene and Thème de la drogue (the drug theme) for the opium den scene.

Raphaël Millet is a film director, producer and critic with a passion for early cinema. He has published two books, Le Cinéma de Singapour (2004) and Singapore Cinema (2006), as well as directed documentaries such as Gaston Méliès and His Wandering Star Film Company (2015), screened as part of the 2015 Singapore International Film Festival, and Chaplin in Bali (2017), which opened the Bali International Film Festival in 2017.

Raphaël Millet is a film director, producer and critic with a passion for early cinema. He has published two books, Le Cinéma de Singapour (2004) and Singapore Cinema (2006), as well as directed documentaries such as Gaston Méliès and His Wandering Star Film Company (2015), screened as part of the 2015 Singapore International Film Festival, and Chaplin in Bali (2017), which opened the Bali International Film Festival in 2017.

NOTES

-

So Darling So Deadly (1966; original title Kommissar X – In den Klauen des goldenen Drachen) is a co-production between Austria, Italy, West Germany, Yugoslavia and Singapore, and directed by Italian filmmaker Gianfranco Parolini under his American pseudonym Frank Kramer. It was set – but not entirely filmed – in Singapore; some images of Hong Kong were inserted. ↩

-

Suicide Mission to Singapore (1966; original title Goldsnake: Anonima Killers, but also known in German as Goldsnake, Das Geheimnis der goldenen Schlange) is a co-production between France, Spain and Italy. Also set and shot in Singapore, the film, directed by the Italian filmmaker Ferdinando Baldi, tells of a secret agent who travels to the island-city to solve a mystery. ↩

-

Slater, B. (2012, September). Cinq gars pour Singapour. Cinematheque Quarterly, 1(1), 48–56; Slater, B. (2015, Apr–Jun). Spies, virgins, pimps and hitmen: Singapore through the Western lens. BiblioAsia, 11(1), 20–23, p. 21. (Call no.: RSING 027.495957 SNBBA-[LIB]); Millet, R. (2006). Singapore Cinema (p. 147). Singapore: Editions Didier Millet. (Call no.: RSING q791.43095957 MIL). Codelli, L. (2014). Five Ashore in Singapore aka Cinq gars pour Singapour aka Cinque Marines per Singapore (1966). In L. Codelli (Ed.), World film locations: Singapore (p. 42). Bristol: Intellect Books. (Call no.: RSING 791.43025095957 WOR) ↩

-

Bond spin-offs, spoofs and parodies often used three-digit prefixes, such as 008, 077, X77, S3S, and because of that it has often been easy to mistake OSS 117 for another pale copy of the original. However, it is far from the truth. By the time the first James Bond book was published in 1953, Jean Bruce had already published several OSS 117 novels. He was such a prolific writer that he wrote about 90 books altogether (including the OSS 117 series) before his untimely death in a car accident in 1963 at age 43. ↩

-

In the mid-2000s, the character of OSS 117 was revived on screen by filmmaker Michel Hazanavicius as a French spy working for the French secret service and turned into a comic character, portrayed by French actor Jean Dujardin as an arrogant and blatantly politically incorrect imbecile (far from the original OSS 117 character and his previous screen incarnations). ↩

-

This would lead to the Second Indochina War, better known as the Vietnam War (1955–1975), fought between North Vietnam (supported by communist China and the Soviet Union) and South Vietnam (supported by anti-communist allies, including the United States, Australia, South Korea and Thailand). ↩

-

Bernard Toublanc-Michel’s interview with the author, 1 June 2018 ↩

-

French press kit of Cinq gars pour Singapour, 1967, p. 13. ↩

-

Saint Jack, shot entirely in Singapore between May and June 1978, was banned in January 1980 as local authorities felt that it portrayed the city negatively. The ban was lifted only in March 2006, with the film given an M18 rating. The film had its first official public screening in Singapore in 2006. More on Saint Jack, see Slater, B. (2006). Kinda hot: The making of Saint Jack in Singapore (p. 240). Singapore: Singapore: Marshall Cavendish Editions. (Call no.: RSING 791.430232 SLA) ↩

-

Bernard Toublanc-Michel’s interview with the author, 1 June 2018. ↩

-

Bernard Toublanc-Michel also thought of offering the role of Art Smith to Joe Dassin, son of Hollywood director Jules Dassin and a French woman. Like Sean Flynn, Joe Dassin was Franco-American and fluent in both English and French. In the end, Toublanc-Michel decided to cast Sean Flynn as he had experience working and living in Southeast Asia, and a better understanding of the geopolitical context of the plot. Interview with the author, 1 June 2018. ↩

-

Bernard Toublanc-Michel’s interview with the author, 1 June 2018. ↩

-

French press kit of Cinq gars pour Singapour, 1967, p. 14. ↩

-

Slater, Sep 2012, p. 55 ↩

-

Bernard Toublanc-Michel recalls having thought of Raoul Coutard, the most famous of all New Wave cinematographers, whom he had previously worked with, to shoot Five Ashore in Singapore, but this did not happen as Coutard was already hired for another film. Interview with the author, 1 June 2018. ↩

-

Interview with the author, 1 June 2018. ↩

-

Lombard, P. (2011). Sean Flynn: L’instinct de l’aventure (pp. 86–87). Paris: Editions du Rocher. (Not available in NLB holdings) ↩

-

Lombard, 2011, pp. 86–87 ↩

-

French press kit of Cinq gars pour Singapour, 1967, p. 3. ↩

-

French press kit of Cinq gars pour Singapour, 1967, p.4. ↩

-

Bernard Toublanc-Michel’s interview with the author, 1 June 2018. ↩

-

Dennis Berry was the son of the famous Hollywood director John Berry. The latter had escaped the United States in the early 1950s due to accusations of being a communist. ↩

-

Marika Green would subsequently appear in infamously famous French softcore porn movie Emmanuelle in 1974, in another Asian setting: Bangkok. ↩

-

It is not known whether “Boss” is the actor’s real surname. ↩

-

At the time of writing of this article, the role of Tsi Houa is wrongly credited on both Wikipedia and IMDb to “Foun-Sen”. Foun-Sen was a French actress of Vietnamese origin, and she was definitely not part of the cast of Five Ashore in Singapore. ↩

-

Listed in IMDb by this title ↩

-

Sam, J. (1966, October 1). Solved-that Men from U.N.C.L.E riddle. The Straits Times, p. 12; When the kissing couldn’t even get started. (1966, October 2). The Straits Times, p. 3. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩