Life Lessons in a Chetty Melaka Kitchen

Thrift, hard work and resilience are qualities that can be nurtured through food. Chantal Sajan recalls the legacy of her grandaunt.

There was a time – before the invention of modern kitchen miracles such as electric blenders and KitchenAid – when Chetty Melaka1 families in Singapore plated up a veritable cornucopia of Indian Peranakan dishes on a very tight budget, using the simplest of kitchen utensils.

There were the lesung (granite mortar, usually sold with a matching granite pestle) – the “eclectic blenders” of the era – which could pulverise, mash up and liquefy almost any ingredient known to man. With such simple but sturdy early-day “appliances”, one hardly needed the KitchenAid either. And there was no need to go to the gym too: the arduous pounding made sure one had quite a workout – to say nothing of toned arms.

Through skillful time management, the freshest produce and a system of cooking that entailed pegang tangan (touch of hand), the matriarchs of Chetty Melaka kitchens prepared food that hardly needed refrigeration, with their uncanny sense of pegang tangan greatly reducing wastage – from the food preparation stage right through to the quantity served.

It was anathema in our family to write down recipes. Everything was passed down through the generations by agak-agak (guesswork). If you got it wrong, you had to finish your mess yourself – and God forbid any chucking of food down the rubbish chute.

Food wastage is such a cardinal sin in Chetty Melaka kitchens that – even to this day – the matriarchs would consume the leftover food themselves rather than invoke the wrath of Annapurni, the resident kitchen deity of Chetty Melaka families, who although dress and speak like Malays, are staunch Hindus. The goddess, we were all taught even before we grew our front teeth, presides over the making of food, so every precious morsel wasted is an insult to her.

Because of this, we grew up valuing money even more – that by cleaning our plates, we were building up our store of merit by honouring the work of those who had slaved in the kitchen all day to put food on the table and also to those who worked all day to make it possible to buy the produce and the ingredients in the first place.

This deeply ingrained value would, in our later lives, hold us in good stead when we procured ingredients from the supermarket, mentally calculating how much we needed to prepare our dishes without buying in excess – so that food did not sit in the fridge and spoil.

I can still remember my grandaunt Salachi Retnam, who became my mother’s guru in everything fragrant, aromatic and downright mouth-watering relating to food after my grandmother had passed on in the 1980s.

In 1991, she was the subject of a cover story by food writer Violet Oon for her culinary magazine, The Food Paper. Ms Oon interviewed my grandaunt and my mother on the fading art of Indian Peranakan cuisine, together with photographer-turned-food writer K.F. Seetoh, who also shot a few photos for our family album.

Achi Atha, as we called our grandaunt (atha is the Tamil word for “grandmother”, making no distinction between grandmother and grandaunt), was born at the turn of the century in 1903, a British subject who lived with her uncle in Katong after her parents passed on early in her life.

Achi Atha came under the care of her unmarried uncle and his sisters, and was taught the intricacies of Chetty Melaka traditions. She lived through World War I as well as the Japanese Occupation of Singapore during World War II.

According to her granddaughter (and my cousin) Madam Susheela, Achi Atha would wake up at the crack of dawn to make sure breakfast, lunch and dinner were taken care of, and then she would prepare the “kueh menu” for the day.

“Atha would gather bunga telang (butterfly pea flowers) to extract its blue dye for popular desserts like pulut inti and kueh dadah, and then she would prepare inti (grated coconut cooked with gula melaka and pandan leaves) to be used as fillings for these desserts, all of which were usually made “a la minute” when an unexpected guest dropped by”, she said.

Even in such frugal times as between the two world wars, Achi Atha always had something homemade and sweet on hand for guests. “No one was allowed to leave without a drink or a dessert,” said Madam Susheela. “That was the custom in our ancestors’ homes, which has continued in our lives until this present day.”

For Hindus, the mantra “the guest is God” – from the Sanskrit Atithi devo Bhavah – has manifested in the age-old Chetty Melaka practice of honouring any guest with warm hospitality and food and drink, even if they visit our homes unannounced.2 Chetty Melaka women are known not only for their Malay-Indian dishes but also for their Straits-influenced grooming and attire. Like the Chinese Peranakan (Straits Chinese), they were resourceful in every aspect of their culture.

My grandaunts and grandmother would frequent Geylang Serai or Arab Street to buy kain lepas (sarong kebaya, which were sold in 4–5-metre lengths), and they would tie these wraps in such a way that would allow them free movement to do their housework – from squatting over a charcoal stove to climbing the jackfruit tree to slice off ripe backyard produce to even bedtime, with a change of their very diaphanous blouses that showed a plain chemise underneath. No nighties needed – why allow that extra expense?

Even their hair had to be neatly combed with scented oil to make sure not a strand was out of place. To achieve this, the matriarchs used a single thread that they held tightly around the hair starting from the crown and down to the ends of their tresses – to catch every stray, non-compliant strand. This was all neatly coiffed into a cucuk sanggul – or chignon bun.

Hairdressers and hair salons hardly did any brisk business with these tight-wadded, chignon-sporting women looking their best, even on a windy, bad-hair-day afternoon. Their shoes, which matched their kebaya outfits, were embellished with indigenous beaded designs in a recurring leitmotif.

Even when she was well into her mid-90s, when she turned up early in the morning to advise my mother on the finer points of cooking ayam buah keluak,3 my grandaunt parlayed raw produce, fowl and grains into scented rice, rich, curries and melt-in-the-mouth desserts without breaking a sweat.

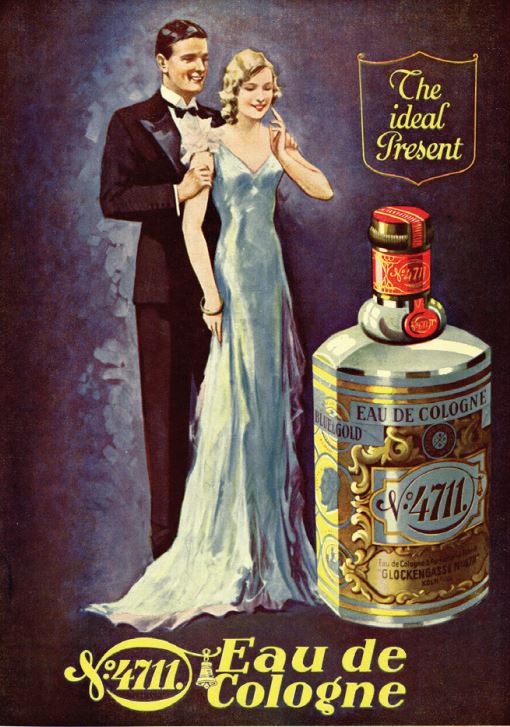

The perfume du jour since the early 1900s among Chetty Melaka women was none other than that must-have curio of scents, the 4711 Eau de Cologne – and my grandaunt literally bathed in it. She also swore that it fended off almost every malady known to man– from cooling the body down to curing insomnia and even the common cold. Now, how many of us can boast that our French perfume can multitask like that in the sweltering Asian heat? That tiny bottle of Eau de Cologne, conceived in 1792 in Germany, certainly punched way above its weight.

By the early 1980s, my mother had already become quite the exponent of this Indian sub-culture’s cuisine. She had learnt how to prepare curry powder – not from store-bought packets – by manually drying the raw ingredients under the sun and then getting them milled in Little India in big batches that could last for up to three months when kept in the fridge.

Coriander seeds were dried in the sun on flat baskets, which also acted as sieves to drain out excess water. So were cumin, fennel, dried chillies and fenugreek seeds. These were later combined to make curry powder for vegetable curries, meat and fish dishes.

The homemade curry powder, if done according to matriarchal dictates, never stuck to the pan when it hit the oil, as no flour or fillers were allowed. And that meant that one needed to use less of these spice mixes, as they were potent dish enhancers.

This is also where the pegang tangan approach comes in handy during the cooking process – the touch of hand that allows the cook to use the spices judiciously with no wastage; just by the touch of the hand, one can intuitively gauge how much chilli powder to add for heat, and how much curry mix to put in the ayam buah keluak so that it does not overpower the distinctive taste of the buah keluak.

It is an alchemical moment when cook, spice and ingredients are almost immersed in some sort of inexplicable kitchen Zen, on a level beyond the abilities of lesser neophytes, who can only pore over recipe books, trying to cook by rote.

For the interview with Violet Oon, in just one morning, my mother had whipped up a chicken curry, a dry-fry mutton Mysore dish, a fish stew, ikan panggang (grilled fish), stir-fried vegetables, Indian Peranakan chap chye (braised mixed vegetables), fragrant basmati rice, a range of yogurt accompaniments made with mint and pomegranates, and desserts – rich, chocolate cake and Malay-style coconut candy. My grandaunt’s disciple had truly come into her own.

Nothing goes to waste, true to the teachings of my grandaunt – as after the photo shoot, there were takeaway boxes on hand for everyone as well as another round of guests in the evening that my mother had scheduled earlier that day – to finish up every last grain of pandan-infused and cardamom- and cinnamon-enhanced basmati rice and curries.

Achi Atha passed on two years after that great repast, followed by my mother six years later. But their teachings and their culinary values have gone on to inspire every other aspect of their children’s, grandchildren’s and great-grandchildren’s lives.

The lessons in the kitchen taught us to be prudent, resourceful, hardworking and frugal, and yet to always seek a richness in our lives through well-prepared dishes made from the freshest, and not necessarily, the most expensive of ingredients.

This article was first published in The Sunday Times on 5 August 2018. © Singapore Press Holdings Limited. Reprinted with permission.

Chantal Sajan is a sub-editor with Singapore Press Holdings. She currently works in the newsroom of The Business Times.

Chantal Sajan is a sub-editor with Singapore Press Holdings. She currently works in the newsroom of The Business Times.

Notes

-

Also spelled as Chetti Melaka or Chitty Melaka. The Chetty Melaka are descendants of South Tamil Indian traders who settled in Malacca during the Malaccan Sultanate (1400–1511) and married local women who included Malays, Javanese, Bataks and Chinese. Chetty Melaka are mostly Hindu, and speak a patois of Malay, Tamil and Chinese. The community of some 500,000 in Singapore traces its roots to Kampung Chetti at Jalan Gajah Berang, Malacca. ↩

-

This is extended only to those we are accustomed with, and not to rank strangers. The rule was that when in doubt about a guest, never allow them to enter but apologise a few days later after you have established their relationship to the family. ↩

-

Buah keluak is a poisonous seed from the kepayang tree, native to Malaysia and Indonesia, which is “cured” of its cyanide content by a careful process of boiling, immersion in ash and followed by burial in the earth for a certain period of time. ↩