The Modern Malayan Home

Along with the introduction of running water and electricity at the turn of the 20th century were advertisements featuring modern home appliances. Georgina Wong has the story.

(Right) Singer put out many creative and visually interesting ad campaigns targetted at women, as evident in this 1961 ad. Image reproduced from The Straits Times Annual, 1961, p. xi.

Modern utilities and amenities revolutionised home life across the world in the early 20th century, and Singapore was no exception. What it really boiled down to was the introduction of gas, electricity and running water to households. In their wake, a vast array of appliances that made use of these modern utilities soon appeared on the market, radically changing the way people cooked, cleaned and entertained themselves at home.

Singapore’s march to modernity from the 19th century onwards was not without its complications. This was primarily due to the vastly differing living circumstances and situations of the population at the time. Most European expatriates – who lived in the city centre and its environs in “modern” homes made of brick – were generally the first to receive new amenities such as sanitation and electricity. The majority of the Asian population, on the other hand, were either living in attap houses in kampongs (villages) on the outskirts of town and beyond or crammed into tenement shophouses well into the 1960s. Unfortunately, the physical construction of these dwellings did not facilitate access to modern amenities.

A major factor in the modernisation of the home was the introduction of running water and proper sewerage. Prior to 1910, the use of night-soil buckets was the primary means of waste disposal, the term “night-soil” being a polite term for human excreta. Residents would pay night-soil collectors to remove their human waste from outhouses – literally a shed outside the main dwelling – for use as fertiliser in gardens and plantations. The implementation of islandwide sanitation was a massive infrastructural project, and it was not until 1987 that the night-soil system was finally phased out.1

Running water was another issue that took many decades to resolve. While wealthier households in the town centre had access to piped water by the mid-1800s, some villages were still drawing water from communal pumps and wells as recently as the 1950s.2

Naturally, in those early days, modern home appliances like electric washing machines were targeted at those who had access to running water and electricity. Until the 1950s and 60s, when more residents had been relocated to public housing that could support a full range of utilities, only a handful of dealerships importing home appliances existed.

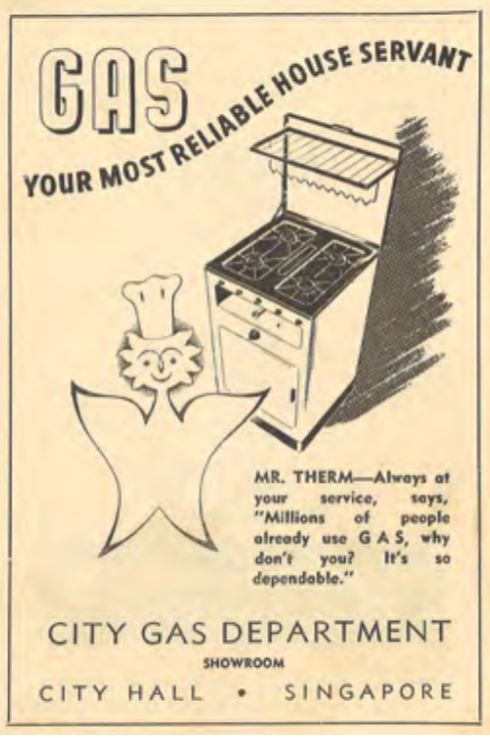

Gas and Electricity

Before the advent of gas and electricity in Singapore, the energy source for municipal and household uses, such as street lighting and cooking, came from the burning of oil, coal and wood. In 1862, Singapore Gas Company opened Kallang Gasworks, the first plant dedicated to manufacturing gas for street lighting.3 In 1901, gas production was taken over by the Municipal Commission and expanded for home use.4

Electricity followed soon after: in 1906, Raffles Place, North Bridge Road and Boat Quay became the first streets to be lit by electric lighting.5 Electrical supply was made available for private use soon after, albeit only to households that could support and afford the installation of wiring systems.

As a result, home gas and electricity became commonly advertised in newspapers, books and magazines, with the messaging revolving around their economic benefits, reliability, safety and convenience. Through the medium of print advertisements, the municipal gas and electricity departments took pains to assure customers that the energy saved in the long run would be worth the relatively large start-up cost of installing gas pipes and electrical wiring in their homes.

Modern Home Gadgets and Appliances

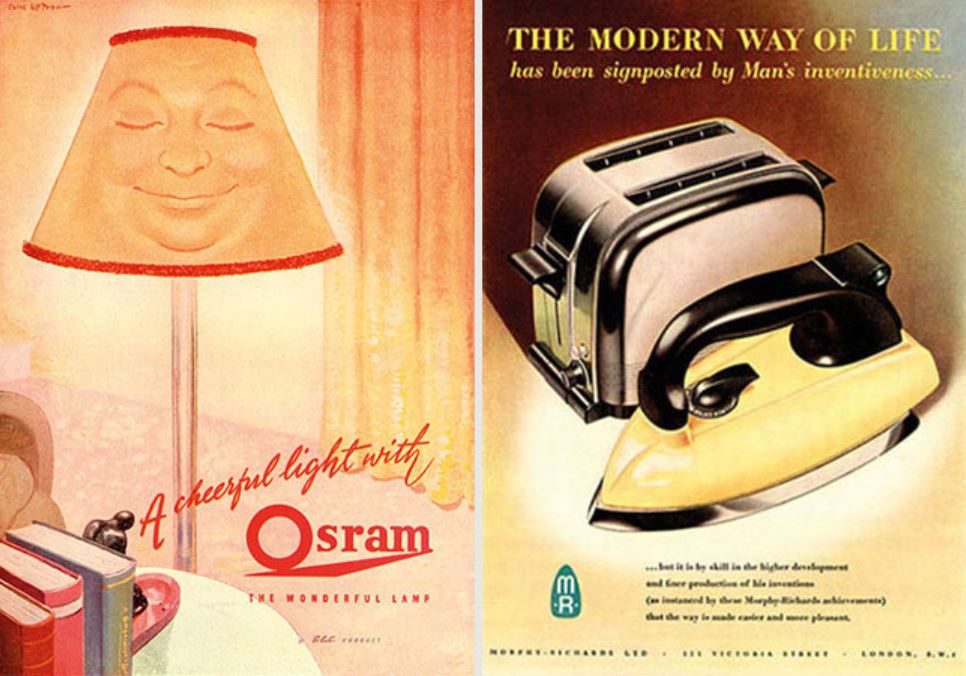

The introduction of electricity in the home fuelled demand and created a consumer market for household goods and entertainment, resulting in a flood of new inventions from the United States, Europe and, later, Japan. Besides home staples such as electric lights, appliances such as refrigerators, blenders, electric irons, ceiling fans and vacuum cleaners were also heavily advertised in the early 20th century.

In general, the advertising of household goods in Malaya was undertaken by local dealerships as well as the department stores that imported them. However, major brands such as General Electric Company, Morphy-Richards and National also placed advertisements for their own products, as they had the means to run extensive advertising campaigns to promote their goods in what had become a fairly competitive market for household products.

Initially, only the more affluent had the means to purchase modern household appliances. For example, an electric iron advertised in The Straits Times in 1947 cost 11.50 Straits dollars,6 which was equivalent to almost two months of a factory worker’s wages at the time.7 By the 1950s and 60s, however, such appliances had become much more affordable to middle-class households.

Home goods were often touted as essential to the “modern home”. The “ideal household” was a concept that had existed long before the introduction of electrical home gadgets but thanks to a slew of advertisements in the early decades of the 1900s, it soon came to mean a home that was fully equipped with modern conveniences such as a washing machine, gas stove, refrigerator, electric lighting, fans and even air-conditioners. Smaller appliances like electric irons and hair dryers were marketed as practical gifts to buy for friends and loved ones to help make their lives a little easier.

(Right) Ads such as this one for Morphy-Richards appliances in 1953 were mostly found in newspapers and magazines read by the more well-to-do. The “modern” way of life was cast as an aspirational ideal. Image reproduced from The Straits Times Annual, 1953, p. 14.

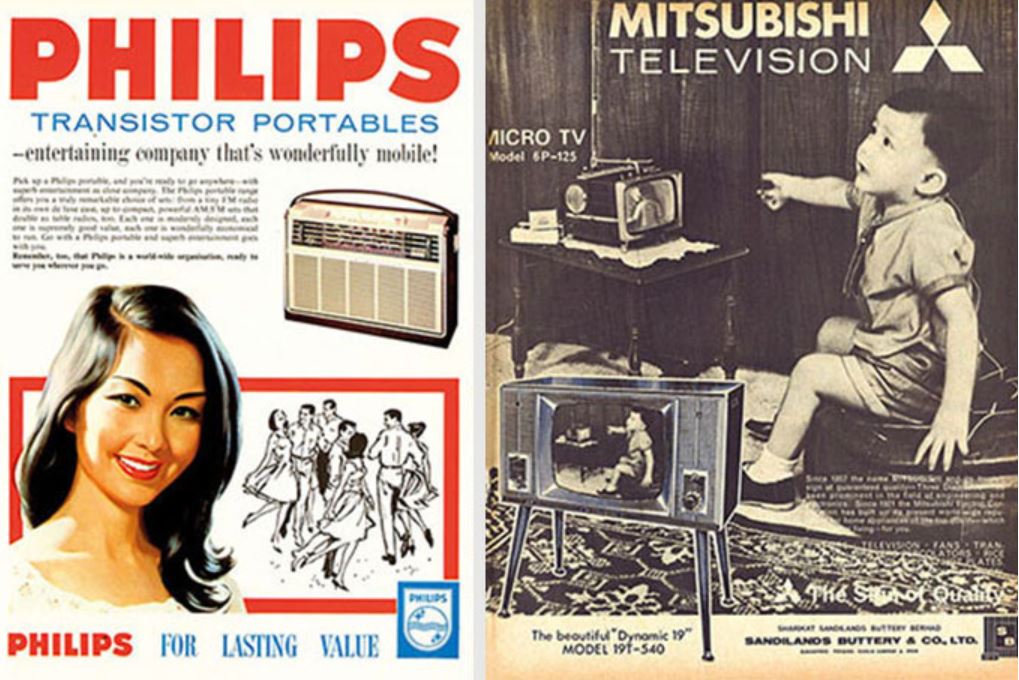

Home Entertainment

One of the most exciting introductions to households in the mid-20th century was home entertainment in the form of radio, television and the gramophone. These innovations grew to become household staples in Singapore, creating an entirely new way for families to spend their leisure time. One could enjoy vinyl recordings of popular and classical music, radio and television shows and dramas, daily news from around the world as well as sports and racing commentaries and broadcasts – all from the comfort of one’s home. Radio and television would eventually grow to dominate media and communication around the world, with advertisers quickly adopting these new media to sell their goods and services.

On The Radio

Radio broadcasting in Singapore began as a niche interest in 1924, with the Amateur Wireless Society of Malaysia (AWSM) effectively the preserve of the wealthy wireless enthusiast.8 This was soon followed by the establishment of Radio Service Company of Malaya in 1933, which set up Radio ZHI and British Malaya Broadcasting Corporation in 1935.9 By the 1930s, radios in Singapore could receive shortwave broadcasts from around the world, such as the Empire Service of the British Broadcasting Corporation (now the BBC World Service).10

However, local demand for radios was slow on the uptake: in 1929, the Federated Malay States government received applications for only 119 radio licences, compared with the 1,000 issued in Hong Kong the same year. This was largely due to misguided public opinion on the reliability of radio reception and the longevity of radio mechanisms in the tropics. It was commonly thought that radio parts would easily rust and warp in the humid Malayan weather, and that the lack of radio engineers or technicians in the region meant that there might be no real hope of repair.11 As a result, advertisers throughout the early 20th century went out of their way to assure customers that their radio models had been specially made to withstand the tropical climate.

Unsurprisingly, the growth of the industry was driven mainly by the providers of radio services and products, who stoked demand via advertising. The founders of the early broadcasting groups, such as AWSM, were representatives of companies with a vested interest in developing a radio audience, such as General Electric and Marconi’s Wireless Telegraph Company.12

As demand for radio sets increased and prices became more affordable, dealers began importing the latest models from various brands. To distinguish themselves from the competition, advertisers would boast of the reliability and reception quality of their products, and assure buyers that they were purchasing the best and latest technology available in the market.

(Right) A 1966 Mitsubishi ad for a “micro TV”. Image reproduced from Her World, January 1966, p. 9.

Turn on the Telly

The first television station in Singapore, Television Singapura, aired the first broadcast on 15 February 1963, which ran for five hours. It featured the national anthem, an address by then Minister for Culture S. Rajaratnam, followed by a documentary programme on Singapore, cartoon clips, a newsreel, a comedy programme and a variety show.

Singapore households readily embraced television – the first broadcast was watched at home by 2,400 families as well as by members of the public gathered at Victoria Memorial Hall and 52 community viewing centres spread across the island.13

Some of the earliest programmes aired in Singapore were Huckleberry Hound, Adventures of Charlie Chan and local variety shows like Rampaian Malaysia, which featured music from various local ethnic groups.14

Advertisements for television sets not only emphasised their high-quality picture and sound reception, but also promoted the idea that with their “luxury styling” and “cabinet construction”, these new entertainment devices would double up as attractive furnishings for one’s living room.

WHO RUNS THE HOUSEHOLD?

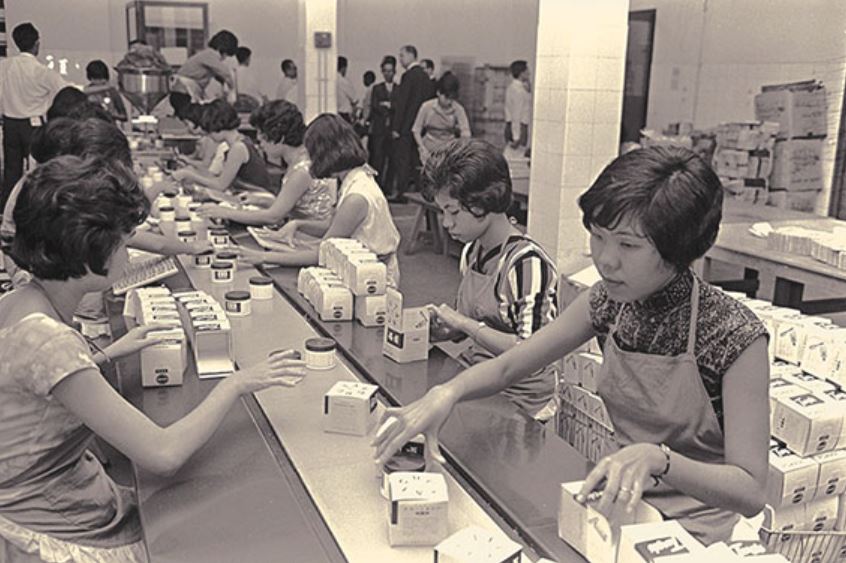

From the early 20th century onwards, many advertisers of household- and domestic-related goods in Malaya began to target women as their main audience.15 An overwhelming number of advertisements featured women – and very rarely men – as the main consumers and users of home technology.

The prevalence of such advertisements – unprecedented before the advent of pictorial advertising.16 – reflected as well as influenced public perception of women’s roles in society: the fairer sex was often depicted as belonging in the domestic sphere, and responsible for caregiving and house-hold management.17

Advertisements published in Singapore during this time mostly portrayed women – of various ethnicities and economic backgrounds – posing with household goods while looking glamorous alongside high-end appliances, or else engaged in domestic chores such as cooking, sewing or doing laundry. A rare household ad targeted at men in 1969 promoted Singer sewing machines as good gifts for their wives.18

By the 1950s and 60s, women in Singapore began entering the workforce in fairly large numbers, but were generally still expected to undertake housekeeping and child-rearing as their primary tasks. This doubling up of duties, among other reasons, relegated many women to shift work and other relatively less demanding lower-paying jobs, such as factory or secretarial work, so that they would have the time to take care of the home after work hours.19

With this in mind, most household appliance advertising focused on making women’s lives easier. Advertisements stressed how the cost of purchasing modern household products would be more than amply justified by the reduced time and effort spent doing housework and, in the process, reward the busy woman with a more stress-free and simple life.

More importantly, advertisers tried to mould public attitudes to suit household consumerism, for instance, by imbuing housework with notions of idealism and romanticism. Advertisements sometimes implied that the work performed by a woman around the house was not done out of necessity but more as a labour of love, and that the care she put into it was an indication of her love for her husband and children. Purchasing household appliances that allowed housework to be done better and faster was therefore an investment of care in the family, a symbol of a woman’s dedication to her primary role as wife and mother.20

This essay is reproduced from the book, Between the Lines: Early Print Advertising in Singapore 1830s–1960s. Published by the National Library Board and Marshall Cavendish International Asia, it retails at major bookshops, and is also available for reference and loan at the Lee Kong Chian Reference Library and selected public libraries (Call nos.: RSING 659.1095957 BET and SING 659.1095957 BET).

Georgina Wong is an Assistant Curator with the National Library, Singapore, and co-curator of the exhibition, “On Paper: Singapore Before 1867”.

Georgina Wong is an Assistant Curator with the National Library, Singapore, and co-curator of the exhibition, “On Paper: Singapore Before 1867”.

Notes

-

The disposal of night soil at Singapore. (1894, January 19). The Straits Times, p. 3. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Staines, V. (1949, May 21). Water is their main problem. The Singapore Free Press, p. 4. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Municipal Council. (1862, June 14) The Straits Times, p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Energy Market Authority. (2016, December 20). Singapore energy story. Retrieved from Energy Market Authority Singapore website. ↩

-

Energy Market Authority, 20 Dec 2016. ↩

-

“Utility” iron. (1947, February 23). The Straits Times, p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Huff, W.G. (2001, May). Entitlements, destitution, and emigration in the 1930s Singapore Great Depression. The Economic History Review, 54(2), 290–323, p. 305. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website. ↩

-

Chua, A.L. (2016, April–June). The story of Singapore radio: 1924–41. BiblioAsia, 12(1), 22–27, p. 22. Retrieved from BiblioAsia website. ↩

-

Chua, April–June 2016; McDaniel, D.O. (1994). Broadcasting in the Malay world: Radio, television and video in Brunei, Indonesia, Malaysia, and Singapore (pp. 34–37). Norwood, NJ: Ablex Pub. (Call no.: RSING 302.2340959 MAC) ↩

-

Fox, B.J. (1990, March). Selling the mechanised household: 70 years of ads in Ladies Home Journal. Gender and Society, 4(1), 25–40, pp. 27–28. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website. ↩

-

Cowan, R.S. (1976, January). The ‘Industrial Revolution’ in the home: Household technology and social change in the 20th century. Technology and Culture, 17(1), 1–23, pp. 9–10. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website. ↩

-

Fox, (1990, March), pp. 25–40; Quah, S.R. (1980, July–December). Sex-role socialization in a transitional society. International Journal of Sociology of the Family, 10(2), 213–231, pp. 214–215. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website. ↩

-

Singer: Take home a jade lady. (1969). FDAWU Magazine of 1969 (p. 62). Singapore: Food, Drinks and Allied Workers Union. Retrieved from PublicationSG. ↩

-

Wong, A.K., & Ko, Y.-C. (1984). Women’s work and family life: The case of electronics workers in Singapore. East Lansing: Michigan State University. (Call no.: RSING 331.4821381095957 WON); Deyo, F.C., & Chen, P.S.J. (1976). ). Female labour force participation and earnings in Singapore. Bangkok: Clearing House for Social Development in Asia. (Call no.: RSING 331.4095957 DEY); Quah, Jul–Dec 1980, p. 221. ↩

-

Interestingly, according to studies on advertising and gender beyond the 1960s, the representation of women in household roles did not necessarily decrease. Instead, brands attempted to diversify the images of families using household items, with men occasionally shown participating in the upkeep of the household, at least from the late 60s onwards. ↩