Singapore Stopover: The Entertainment Circuit 1920–1940

The city was a major pit stop for visiting entertainers and sportsmen in the early 20th century, according to the writer Paul French.

Most people are familiar with the idea of Singapore as a major transportation and shipping hub. There is no lack of historical documents that point to its role as an entrepôt that facilitated trade between the East and West for centuries past.

Less familiar, perhaps, is the notion of Singapore as a key nexus in the regional and global entertainment circuit, not only for the performing arts – dance, theatre and variety shows – but also for popular commercial sports such as boxing.

The island-city’s role as the one-time regional centre of the thriving entertainment industry can be attributed to two factors: first, its position as a multicultural centre with a sizeable European population homesick for Western-style entertainment and sport (and which also enjoyed patronage by some local residents); and second, its geographic location which made it the ideal stopover for entertainers and sportsmen travelling from Europe and heading to China, Australia, Japan and other points east of Singapore, and, in the case of boxers, Australians especially who stopped here en route to bigger and more profitable matches in Europe.

Until now, the role of Singapore as a hub for regional entertainment and sports has not been formally documented by the academic community. Rather, these threads have begun to emerge from the work of academics who write for popular audiences. Many of these writers uncovered this phenomenon in the course of their research.

One such example is Andrew David Field’s Shanghai’s Dancing World: Cabaret Culture and Urban Politics 1919–1954 (2010), which traces the rise and fall of the dance industry in Shanghai as well as the movement of artistes between this city and Singapore. Another interesting subject is that of fashion trends in Lee Chor Lin and Chung May Kheun’s In the Mood for Cheongsam: A Social History, 1920s to the Present, which documents the movement and adaptation of the elegant form-fitting Chinese dress throughout Asia, including Singapore.1

Ferreting through the collections of Singapore’s National Library on the subject of early 20th-century Chinese treaty port history whilst researching my books Midnight in Peking and City of Devils: A Shanghai Noir,2 I was alerted to a series of intriguing leads relating to European and Australian entertainment troupes who toured the region during this period. Along with these accounts were stories of boxers from China, Thailand, the Philippines and Australia, and also further afield from London and Cairo, who made a stop in Singapore to entertain the public and earn some income at the same time.

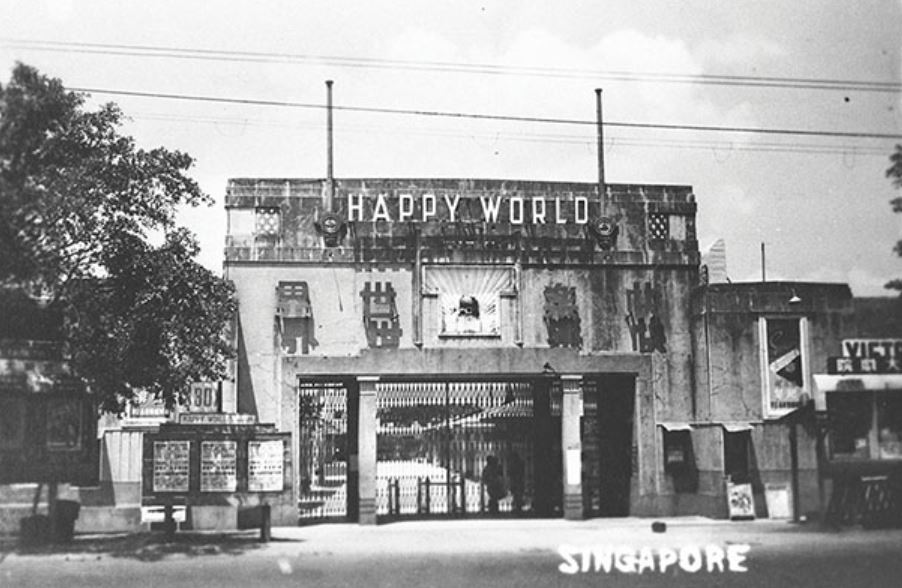

Recent work by Singaporean writers and historians, notably Adeline Foo, on the dancehalls of Singapore’s famous (and now defunct) trio of “World” amusement parks – Happy World in Geylang, Great World along Kim Seng Road and the New World at Jalan Besar – has uncovered additional details on the links between several Chinese cities, Shanghai particularly, and the nightlife and cabaret scene in Singapore in the 1930s and 40s.3

Singapore’s role as a nexus of the entertainment and sports industry between 1920 and 1940 sheds light not only on the myriad forms of entertainment and sports that its residents were exposed to but also important aspects of the sociocultural changes that took place here during this period.

Here are three examples I came across during the course of my research at the National Library. These accounts – mainly gleaned from its newspaper archives NewspaperSG – place Singapore at the heart of the regional and global networks of the entertainment and sports industries in the early 20th century. There are plenty more of such gems, I suspect, buried in the library’s collections and archives just waiting to be discovered.

The Globe Trotters Come to Town

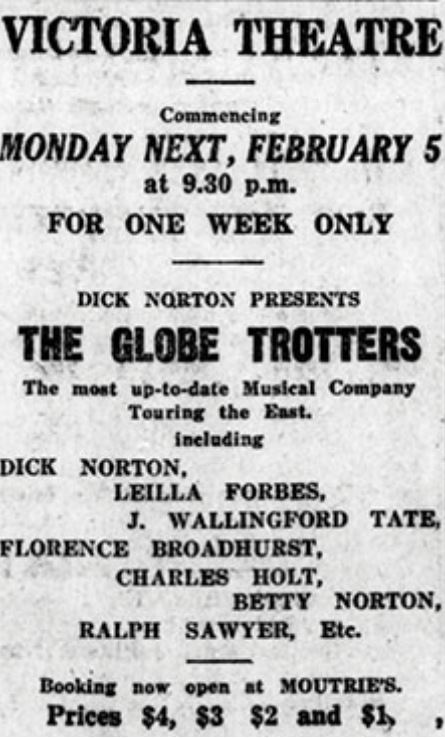

On 5 February 1923, Singapore’s Victoria Theatre played host to the glamorous Globe Trotters, a performance troupe comprising English and Australian artistes. The Globe Trotters was described in The Straits Times as “The Most Up-to-Date Musical Company Touring the East”.4 The troupe was in Singapore for a week, performing nightly at 9.30 pm and received rave reviews from the local press. Among the cast was a young Australian woman named Florence Broadhurst, who performed under the stage name “Miss Bobby”.

After her Singapore engagement, Broadhurst continued to tour Asia with The Globe Trotters for several years, with appearances across Malaya, India and the Dutch East Indies (Indonesia) as well as Hong Kong, Manila and various Chinese and Japanese cities, among other places.

Three years later, in 1926, The Globe Trotters were scheduled to appear in Shanghai, at its Town Hall in the International Settlement5 district. Even before the curtains were raised, the gutsy Broadhurst decided to leave the troupe there and then. After spending some time earning a living by dancing in the city’s famous cabarets, she started her own school – The Florence Broadhurst Academy and Incorporated School of Arts.

The private school initially offered classes in violin, pianoforte, voice production and the banjolele, a cross between the ukulele and the banjo, which Broadhurst had learnt to play while on tour with The Globe Trotters. Soon, the school began offering lessons in modern ballroom dancing, classical dancing, musical culture and even journalism. Broadhurst lived and ran her academy in Shanghai for a year until the bloody riots of spring 1927 erupted, sparked by the violent suppression of communists by Kuomintang forces led by General Chiang Kai-shek.

Broadhurst decided the city was getting far too dangerous for her liking and in the summer of 1927 moved again, this time to London. She would become a famous couturier in pre-war London and then, after returning to her native Australia in 1948, an accomplished water colourist, wallpaper designer and interior decorator. She founded a successful company called Florence Broadhurst Wallpapers, and her signature handcrafted brand of wallpapers was bought over by another Australian after her death in 1977.

In researching the early life of Florence Broadhurst in Shanghai, I wondered about the circumstances that brought her to this Chinese city in 1926. And this in turn led me to discover her role in The Globe Trotters and her time in Singapore.

Broadhurst originally hailed from Mungy Station, near Mount Perry in rural Queensland. She launched her show business career in 1915 when she was just 16 after winning a singing competition. The prize was a chance to sing “Abide with Me” with the legendary Australian soprano Dame Nellie Melba, whose concerts raised substantial sums of money for the Australian war effort during World War I.

Broadhurst subsequently appeared at wartime fundraisers across Australia with an entertainment troupe called the Smart Set Diggers, where she was reportedly a popular contralto. After the war, the troupe broke up and re-formed into several new troupes, including The Globe Trotters, which was managed by Australian theatre impresario and comedian Richard (Dick) Norton. He invited Broadhurst to join his troupe and in 1922 they embarked on a tour of Asia.

The first Australian entertainment troupes actually started touring Asia before World War I. Norton had successfully toured the vaudeville circuit in the Far East with the Bandmann Opera Company (more a theatrical company than strictly opera), which was made up of Australian acts but based at the Empire Theatre in Calcutta, India. Norton had returned home to lend his skills to the war effort but after the war, he realised that there was money to be made in taking variety and entertainment shows to the European colonies in Asia. And thus, The Globe Trotters and others of its kind were born.

The Globe Trotters left Brisbane in December 1922, sailing for Batavia (Jakarta) in the Dutch East Indies first and then on to Singapore in February 1923, where the Victoria Theatre was chosen as the venue for its performances. Advertisements taken out in The Straits Times provide us with the names of other members of The Globe Trotters – namely Leilla Forbes, J. Wallingford Tate, Charles Holt, Betty Norton and Ralph Sawyer.6

As troupes often gained and lost various members during their travels, it is possible to track their movement through the venues they played at and the names of the artistes mentioned in advertisements, flyers and programme booklets. We know that The Globe Trotters featured a couple of comedians, a duo of female impersonators, a pianist and Florence Broadhurst as the troupe’s main singing act. The members of the troupe were involved in a bit of everything: sketches, singing, comedy routines, Pierrot dances (based on a character in pantomime) – in short “putting over a bit of patter”, to borrow a term from showbiz, keeping audiences sufficiently entertained throughout the show.

Singapore was a major stop for visiting theatrical and entertainment troupes from Australia during the period between the two world wars. After Singapore, The Globe Trotters went on to perform in several towns across the border in Malaya, including Kuala Lumpur and Georgetown in Penang, Siam (Thailand) and India (specifically Calcutta and Bombay). The Globe Trotters continued their tour into 1924 with appearances in Hong Kong, Japan and various Chinese cities, including Tientsin (Tianjin), Peking (Beijing) and Shanghai.

Interestingly, while the reviews of The Globe Trotters in Singapore were generally favourable – with The Straits Times proclaiming Broadhurst’s singing as “delightful”, fellow cast member Leilla Forbes’ return to vaudeville as “heralded with success” and praising the troupe as giving yet “another very excellent show” – their performances did not sell out every night.7 The simple reason was that the post-World War I entertainment scene in Singapore and in other major cities in Asia was already saturated with touring companies from Europe, America and Australia.

These foreign troupes were competing with shows put on by newly formed touring companies based in Asian cities such as Shanghai; such troupes comprised largely of émigré Russians who had settled in China after the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917. As these troupes crossed paths in cities like Singapore, entertainers often met in between shows, with many leaving one troupe to join another. This appears to have been the case with our next case study – Joe and Nellie Farren.

From Midnight Frolics to Farren’s Follies

In the 1930s and early 40s, Joe Farren would become the king of Shanghai’s nightlife scene. This was a time when the city was at the height of its fame, earning the sobriquet “Paris of the East”. Dubbed “Dapper Joe” by the local newspapers, Farren had choreographed chorus lines at several of the city’s largest and most famous cabaret venues – the Canidrome for instance in Shanghai’s French Concession and The Paramount Ballroom in the International Settlement, among others.

With his wife and dance partner Nellie, Joe had started out in the late 1920s as an exhibition dancer demonstrating waltzes and foxtrots in a city that was in the throes of a “dance madness”.8 But exactly how did Joe and Nellie Farren end up in Shanghai?

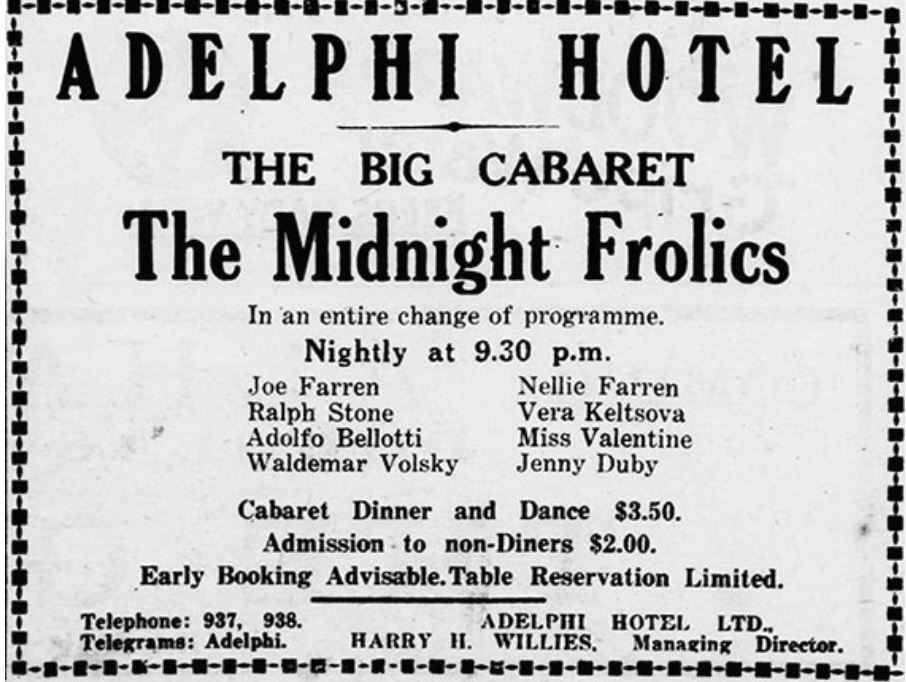

My search for the story of Joe Farren led to Vienna around the time of World War I, where a young Jewish man named Josef Pollak worked as an exhibition dancer in the city’s dancehalls. In 1924, Pollak was recruited to join a troupe of European entertainers called The Midnight Frolics, which was about to leave for a tour of several Asian port cities, including Batavia as well as Kobe and Yokohama in Japan, Manila, and Chinese cities such as Tientsin, Canton (Guangzhou), Peking, Wuhan, Nanking (Nanjing) and Amoy (Xiamen).

The Midnight Frolics were, like The Globe Trotters, a motley crew of entertainers comprising tap dancers, Russian ballerinas, a mouth organist, a singing violinist, a magician and an Italian tenor. Among the recruited Frolics were two émigré Russian sisters Nellie and Eva – both trained in ballet and equally adept at performing mild comic numbers. Pollak was paired with the older sister Nellie, and they became dance partners, and later, husband and wife, anglicising their names to Joe and Nellie Farren.

In January 1928, Joe Farren began organising his own revues in Singapore with a touring American bandleader named Ralph Stone, who later, back in the United States, would include the song “A Little Street in Singapore” in his repertoire. The venue was once again the Victoria Theatre, where their names appeared in a newspaper advertisement as a “Company of Well-known Continental Revue Artists”, billing each of their two-night shows as “Nights of Gladness” and “Dancing Mad” respectively.9

The troupe also staged cabaret shows at the Adelphi Hotel10 – which used to stand on the corner of Coleman Street and North Bridge Road – in January and February 1928, this time calling themselves The Midnight Frolics. At the Adelphi they offered a nightly “Cabaret Dinner and Dance” for $3.50.11

Old newspaper advertisements also provide clues to the evolving nature of entertainment troupes visiting Singapore. Members came and went, some of the troupes took on new names and at various points were joined by other European artistes as well as Russian émigrés and American musicians. To attract new audiences, the troupes frequently added other popular forms of entertainment to their repertoire, such as cabaret shows and tea dances.

In 1929, Joe and Nellie Farren moved to Shanghai, first as exhibition dancers at some of the best hotels in the International Settlement, and then, as part of their own revue. That revue was named Farren’s Follies, with both husband and wife headlining the show. In 1933, Joe returned to Singapore and the Asian entertainment circuit as an impresario with his own troupe comprising mostly Russian émigré dancers recruited in Shanghai.

The National Library’s newspaper archives also reveal other, less salubrious, stories that shed light on the lives of these entertainers. In July 1928, at the end of the Midnight Frolics’ tour of Singapore, The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser reported a case brought before the Civil District Court by one Mrs Alexandra Coublistsky (trading as a milliner under the name Madame Galardi) against Mr Syed Mohamed Alsagoff for $238, being the cost of a white georgette frock, a mauve nightdress and a marocain coat.12

The garments had been supplied to a Miss Nellie Farren, “dancer”, on Mr Alsagoff’s account. Alsagoff, however, claimed that he had not given Miss Farren permission to charge her expenses to his account. The hearing was eventually adjourned with no decision taken. Nellie Farren, as we know, was the Russian dancer with the Midnight Frolics; Mrs Coublistsky, one can assume from her name, was possibly an émigré Russian settled in Singapore and running her own business; while Alsagoff was a member of a wealthy and politically influential Arab trading and property-owning family of Hadhrami ancestry.

The milliner’s claim, although incomplete and possibly alluding to liaisons of an indelicate nature, offers some insights into the interactions between visiting foreign entertainers and local residents. Whatever the reasons were, Joe and Nellie Farren decided to leave Singapore in 1928 for Shanghai to forge a new start.

Friday Night Fights

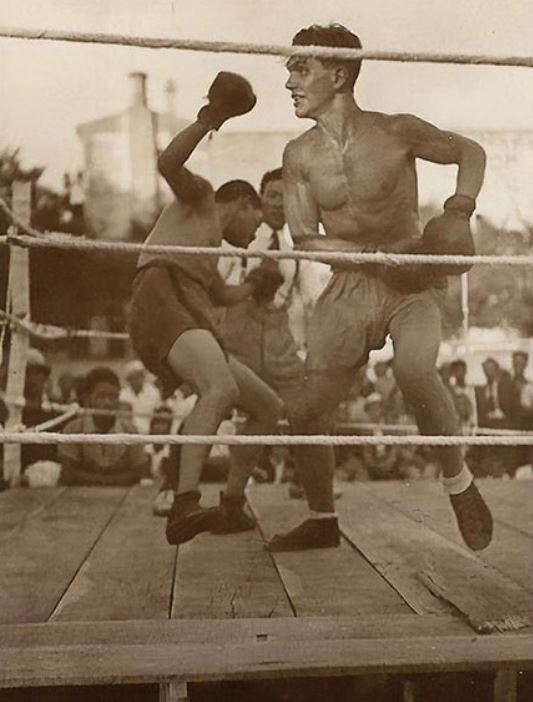

Throughout the 1930s, boxers from all over the world competed for championship belts and prize money at matches held at Asia’s grandest sporting arenas. Dubbed the “Oriental Circuit”, the fighters were frequently on tour and often fought several times a month. Purses were small but regular, although accusations of match rigging dogged many bouts. As with everywhere else, organised crime was never far from the boxing rings in Asia.

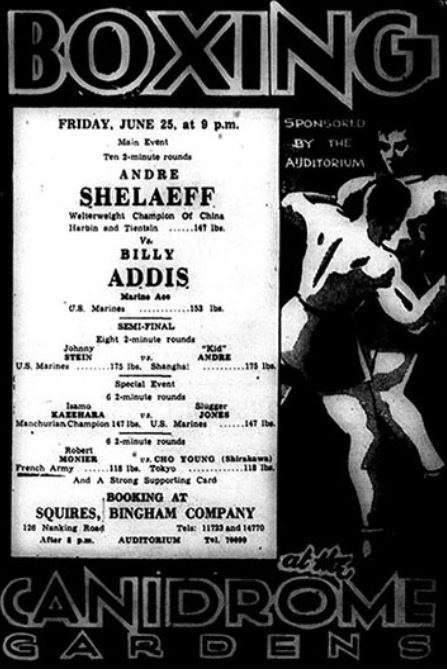

Some of the biggest names in the sport passed through the Oriental Circuit in the 1930s – Young Alde, The Marine Ace, The Japanese Wonder, Clever Henry, the Bronze Bull, Kid Terry, the Siberian Bear, Joe Diamond, Daring Jessy, Kid Andre, Knocker Nokano, Lewko and Young Frisco, among others. But only one boxer ultimately had the guts, gumption and talent needed to make it to the top of the heap. This was Andre Shelaeff, also known as “The Russian Hammer”, a young Russian émigré boy from the Chinese city of Harbin, then known as the “Moscow of the East”.

Shelaeff was born in Harbin in 1919, his parents part of the Russian émigré community that had settled in the Chinese city following the Russian Revolution in 1917. Blessed with both good looks and talent, Shelaeff managed to carve out a successful boxing career in Shanghai, becoming the reigning welterweight champion of both China and the Orient in June 1937.

Having won that title, Shelaeff embarked on a tour of Asia to defend it – first to Manila, and then to Singapore, the regional boxing centre. Singapore was then known as the mecca of boxing in Asia, with most of the bouts taking place at Happy World in Geylang, an amusement park featuring everything from dancehalls, jazz cabarets, circus acts, Chinese opera and Malay bangsawan to roller skating rinks, fairground rides and restaurants. On weekends and on public holidays, upwards of 50,000 people would throng Happy World until the wee hours of the morning.

Shelaeff fought several times in Singapore. The archives of The Straits Times and The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser carry advertisements for all the major fights and include important details such as the weight, height and match records of the boxers.13 Both newspapers employed boxing correspondents to report on the fights, with predictions of who might win before the matches took place. Needless to say, these reports were much sought after by the legions of gamblers placing wagers on the winners and losers.

These newspaper accounts reported that Happy World was regularly packed to full capacity with an audience comprising local residents and foreigners along with personnel from the Royal Navy and British Army stationed in the city.14 The biggest local boxing promoter in the 1930s was Arthur Beavis, a former British featherweight champion in the 1920s who had settled in Singapore.

Poring through the reports written by Singapore’s boxing correspondents between the 1920s and 40s, we see names of Asian boxers from all over the region, including Japan, Thailand and the Philippines, flocking to the island. Singapore was also a major stop for boxers moving between the East and West to seek their fame and fortune. In 1936, Mohamed Fahmy, an Egyptian champion, fought in Singapore as part of a Far East tour. The Cairo-born fighter subsequently left Singapore for England in search of bigger purses.

Mohamed Noor bin Bahiek, also known as Joe Diamond, was born in Mecca and periodically visited Singapore in the 1930s to fight, gaining a large following among the local Malay community.15 South London’s “round-headed and red-haired” Johnny Curly fought in Singapore in 1928 before leaving for a tour of Australia and New Zealand, and returning to Singapore in 1936.

Heading in the opposite direction in 1938 was the Melbourne-based Australian middleweight champion Al Basten, who visited Singapore en route to England for a tour. The boxing scene in Singapore was so vibrant at one time that fans regularly got to see the best fighters from Asia, the Middle East, Europe and Australia battling it out at Happy World on Friday nights.

A Hub for Trade and Entertainment

Singapore’s position as a major touring venue for both entertainment troupes and boxers between the two world wars was largely a spin-off from its role as a key nexus in the regional and global shipping routes. Just about every ship journeying between Europe and Asia, and onwards to Australia and New Zealand, passed through Singapore. This explains perhaps the preponderance of European and Australian entertainers and boxers in Singapore. Occasionally, Americans based in the region visited Singapore on regional tours, but their numbers were few and far between.

Singapore has traditionally been thought of in terms of hard trade, an entrepôt for goods passing through from East to West and vice versa. However, port cities are invariably entry points for ideas, trends and new innovations. In the inter-war period, this exchange of culture included the latest entertainment acts, dances, jazz and big band music as well as sports such as boxing.

Paul French was born in London, educated there and in Glasgow, and lived and worked in Shanghai for many years. His book Midnight in Peking was a New York Times bestseller. His most recent book City of Devils: A Shanghai Noir has received much praise from The Economist. Both books are currently being developed for television.

Paul French was born in London, educated there and in Glasgow, and lived and worked in Shanghai for many years. His book Midnight in Peking was a New York Times bestseller. His most recent book City of Devils: A Shanghai Noir has received much praise from The Economist. Both books are currently being developed for television.

Notes

-

Field, A.D. (2010). Shanghai’s dancing world: Cabaret culture and urban politics, 1919–1954 (p. 50). Hong Kong: Chinese University Press. (Call no.: RART 792.70951132 FIE); Lee, C. L., & Chung, M.K. (2012). In the mood for cheongsam. Singapore: Editions Didier Millet and National Museum of Singapore. (RSING 391.00951 LEE-[CUS]) ↩

-

French, P. (2012). Midnight in Peking. Melbourne, Vic.: Penguin Books, (Call no.: 364.1523 FRE); French, P. (2018). City of devils. New York: Picador. (Call no.: 364.1060951 FRE) ↩

-

Foo, A. (2017). Lancing girls of a happy world. Singapore: Ethos Books. (Call no.: RSING 792.7095957 FOO) ↩

-

Page 7 advertisements column 4. (1923, February 3). The Straits Times, p. 7. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The Shanghai International Settlement was formed form a merger of the British and American concessions in the city. These land concessions were established following the defeat of the Qing army by the British in the First Opium War (1839–42). Later, the French also established its own concession. ↩

-

For examples, see Page 7 advertisements column 4. (1923, February 2). The Straits Times, p. 7; Page 7 advertisements column 3. (1923, February 3). The Straits Times, p. 7; Page 7 advertisements column 3. (1923, February 5). The Straits Times, p. 7; Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The Globe Trotters.(1923, February 3). The Straits Times, p. 10; The Globe Trotters. (1923, February 10). The Straits Times, p. 9; Page 7 advertisements column 3. (1924, January 26). The Straits Times, p. 7; Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Page 6 advertisements column 2. (1928, January 17). The Straits Times, p. 6 Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The three-storey Adelphi Hotel was owned by the famous Armenian Sarkies brothers who were associated with many of Asia’s grand hotels, including Raffles Hotel and the Sea View Hotel in Singapore, the Eastern and Oriental in Penang and The Strand in Rangoon (Yangon). The Adelphi was the oldest hotel in Singapore before its closure in 1973; the building was eventually demolished in 1980. ↩

-

Page 3 advertisements column 1. (1928, January 21). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, p. 3; Page 1 advertisements column 2. (1928, February 2). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, p. 1; Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

A dancer’s frocks. (1928, July 25). The Straits Times, p. 9. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Page 16 advertisements column 1. (1938, May 19). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, p. 16; Shelaeff wins in first minute of first round. (1938, May 21). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser. p. 16; Boxing notes. (1938, June 26). The Straits Times, p. 31; In this corner boxing notes by “spectator”. (1938, August 21). The Sunday Tribune, p. 20. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Boxing attraction at Happy World. (1938, May 10). The Malaya Tribune, p. 14. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Rocky Montanes, who meets Joe Diamond at the New World next Friday. (1935, December 4). The Malaya Tribune, p. 17; Boxing day boxing. (1936, December 15). The Straits Times, p. 7; Around the boxing camps. (1937, April 25). The Sunday Tribune, p. 20. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩