Researching S. Rajaratnam

Writing a biography can be tedious, painstaking work. But the effort can also be uplifting and inspirational, as Irene Ng discovered when she began researching the life of S. Rajaratnam.

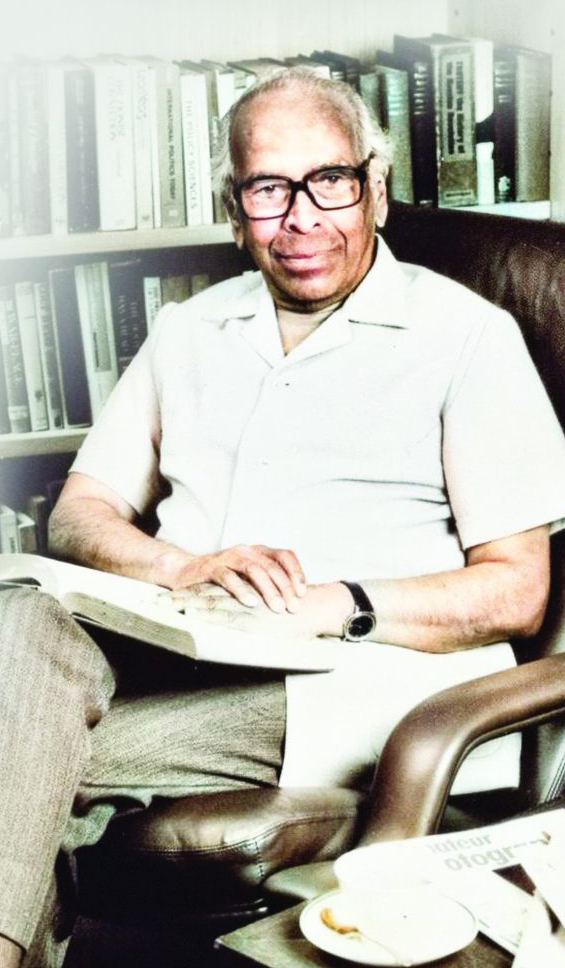

S. Rajaratnam, c. 1970s. S. Rajaratnam Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

S. Rajaratnam, c. 1970s. S. Rajaratnam Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.When I embarked on writing the biography of S. Rajaratnam in 2005, I did not realise that it would take over my life. A project that originally involved just one book became two volumes1 – one already published, another in the making – and a third, an anthology of Rajaratnam’s short stories and radio plays,2 published as a surprise baby in between. And who knows, there might be a fourth book.

It has been a long research journey. I started with the question: how does one capture the complex life of a man who was one of Singapore’s founding leaders, the first minister for culture (1959) of self-governing Singapore, the first minister for foreign affairs (1965–80) of independent Singapore – and the ideologue who wrote the country’s National Pledge in 1966?

S.Rajaratnam during an election mass rally at Fullerton Square, 1 April 1959. Seated sixth from right is Secretary-General of the People’s Action Party, Lee Kuan Yew. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

S.Rajaratnam during an election mass rally at Fullerton Square, 1 April 1959. Seated sixth from right is Secretary-General of the People’s Action Party, Lee Kuan Yew. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.In trying to answer this question, I turned to the archival materials at the National Archives of Singapore (NAS), aptly situated at the foot of the historic Fort Canning Hill. The building, a former schoolhouse, had the feel of, well… an old school with a run-down air (at least when I visited it between 2005 and 2015 for my work). Within the building itself, however, was a treasure trove of old documents, photographs, maps, radio broadcasts and television footage. It is hard to describe the sense of anticipation I feel each time I enter its reading room, ever hopeful that I would come across new insights and learn new ways of understanding the past.

Over the years, I have built a respectful relationship with the NAS as I gained a deeper appreciation of the challenges it has faced in fulfilling its mission. It plays an indispensable role in preserving the primary records of our past, the very essence of our heritage. I don’t think I overstate the importance of the NAS when I say that it is a bastion of social memory and national identity. Yet, all too often, its role is neglected and underappreciated by the public.

I had known Rajaratnam since my days as a journalist and had interviewed him in the 1980s and 90s. Writing his biography may have been the furthest thing on my mind then, but those encounters gave me a sense of the kind of man he was: his thinking, his values, his mannerisms.

By the time I started on his biography in 2005, he was already 90 and suffering from late-stage Alzheimer’s disease. With the permission of the trustees of Rajaratnam’s estate (his Hungarian wife Piroska Feher had died in 1989; they had no children), I browsed his personal library and private papers in his old bungalow in leafy Chancery Lane, a process that continued until some months after his death in February 2006. Other than his vast collection of books, there were the boxes upon boxes of papers, files and photos, all gathering dust.

S. Rajaratnam and his Hungarian wife, Piroska Feher, relaxing at home with a friend (left), c. 1980s. S. Rajaratnam Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

S. Rajaratnam and his Hungarian wife, Piroska Feher, relaxing at home with a friend (left), c. 1980s. S. Rajaratnam Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.I became worried that the materials would deteriorate in the heat and humidity, or worse, be misplaced or destroyed. After Rajaratnam passed away, I recommended that important items be donated to the archives for preservation. So imagine my despair when, during one visit to his house, I saw hundreds of books smouldering in a bonfire in his garden. Thanks to the actions of the NAS and the Institute of Southeast Asian Studies (ISEAS), however, most of his books and other important items, such as his armchair and typewriter, found a new home in their premises.

The experience reinforced my conviction that the images, voices and documents of our founding leaders should be systematically preserved for the benefit of the present and future generations.

Writing Rajaratnam’s biography for me is part of the larger endeavour to preserve memories. Biography is the form through which writers recreate life from archival documents such as letters and diaries, TV and radio recordings, newspapers and official records – in this case, Hansard documents (transcripts of parliamentary debates). This work is vastly different from my previous job as a newspaper journalist. Journalists write the “first draft” of history, chronicling people and events with speed and immediacy in mind. In contrast, biographers may take years – in my case, more than a decade – to complete their account of a subject’s life. I am grateful to all those who have helped me and believed in me throughout the arduous process, particularly my patient bosses at ISEAS.

During my research journey, NAS staff very kindly steered me through their vast collection. They organised dozens of boxes of materials, provided an outline of the files in each box, and even highlighted which boxes might contain the most interesting files that would aid my research.

Pitt Kuan Wah, then director of the NAS, and Ng Yoke Lin, senior archivist, both shared with me useful historical insights into the defining moments of the post-independence era, such as the drafting of the National Pledge. They also alerted me to newly acquired resources, including audiovisual materials, and tracked down additional items to help in my writing – these led me to unexpectedly valuable files. More recently, for the second book on Rajaratnam I am working on, staff at the NAS made it possible for me to access secret files that had to be declassified first.

With their help, I ploughed through thousands of documents, including declassified British and Australian records as well as documents from Singapore’s Ministry of Culture and Cabinet files. I spent hours listening to Rajaratnam’s sound recordings. I watched video footages of him at work, observing his body language, listening to his tone, imagining the emotions – both the elation as well as the angst – of the moment. These multifaceted resources helped me build a nuanced and complex portrait of the man, and to write what I hope is an engaging and authoritative account of his life.

How did I know that Rajaratnam wore a relaxed smile and exuded confidence at the controversial event on 31 August 1963 marking Singapore’s de facto independence? From the archival television footage.

How did I know that he sounded somewhat diffident when he spoke to journalists in his first press conference as foreign minister in 1965? From the sound recordings of the interview.

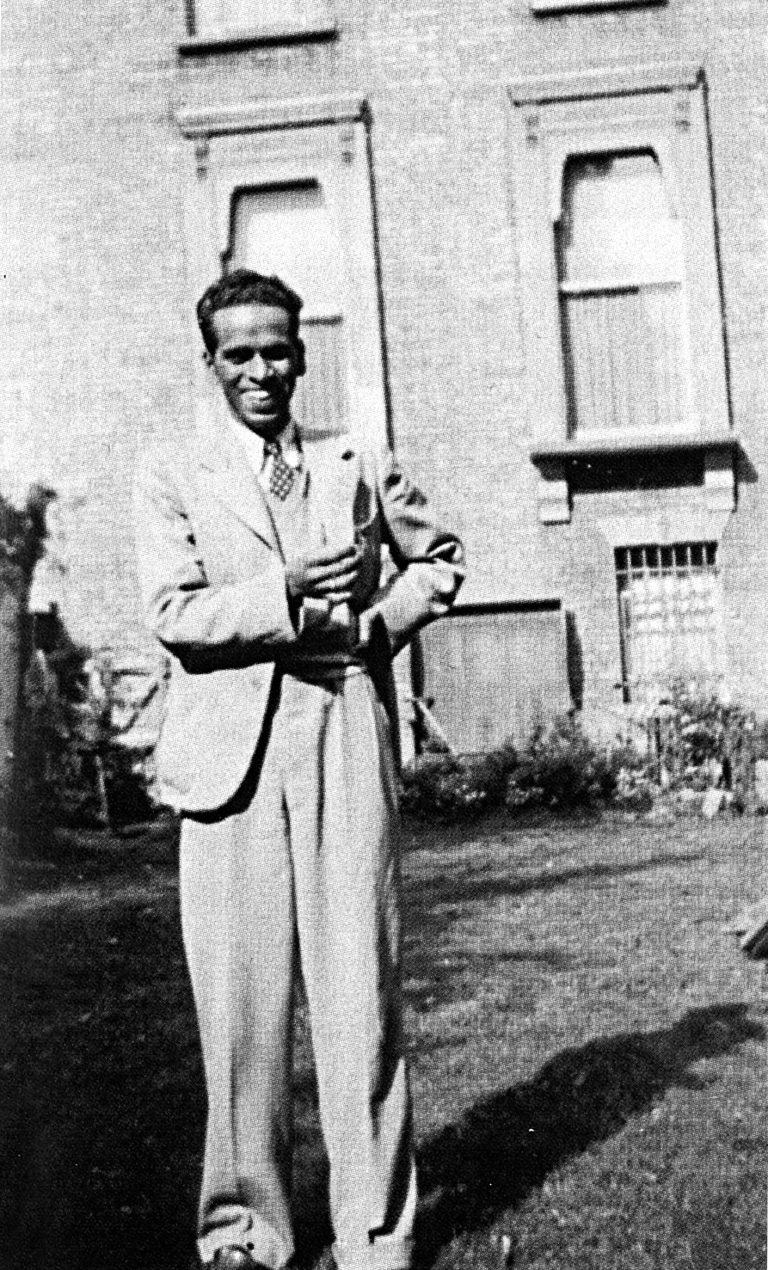

How did I know that he courted the Hungarian girl, who would later become his wife, in late-1930s London, with romantic picnics by the beach, rowing a boat and swimming? From his photos in the archives.

Oral history interviews were another rich resource. When I first started my research in 2005, most of the recordings had yet to be transcribed or digitised – forget about instantaneous online access – so it was a slow and painful slog. For access to records, I had to fill in a form, “Request to Access Oral History Interviews”, which took time to process. All this has now changed. The expansion of the Oral History Centre’s digital platforms and services over the years has greatly eased the work of researchers, especially for those based overseas.

While I conducted my own interviews with more than 100 people, including Rajaratnam’s one-time political opponents, for the book, they were supplemented by oral history interviews from the NAS. These provided me with different perspectives and useful anecdotes that helped to enrich the narrative.

But a caveat: some of the oral history interviewees may have been inaccurate, biased or forgetful in their recollections. Equally, some of the interviewers may not have been as probing as they could have been – they are not journalists after all. In short, the oral histories are as useful – and as fallible – as any written record, so one must sift through the records with a critical mind. But without them, the narratives of the past would be all the greyer.

Then there are Rajaratnam’s personal notebooks of various vintage. From his days as a journalist – at The Malaya Tribune, the Singapore Standard and The Straits Times – he developed a habit of neatly copying out salient or interesting parts of the books he had read into a personal notebook. These included quotable quotes, definitions of theories and ideologies, and references drawn from history. His notebooks, which mirror his constant preoccupations, were particularly rich with references to Lenin, Marx, democracy, nationalism and race-related issues.

In the process, Rajaratnam’s handwriting became as familiar to me as my own. From the size and shape of the letters in his copious handwritten notes, I learnt to distinguish those written in his later years, when his mind was no longer what it was, and make my judgment on their use accordingly.

In addition to the materials in the NAS, I was given special permission to access files kept at the Special Branch – the predecessor of today’s Internal Security Department – on condition that I adhered to the rules of the Official Secrets Act. These files gave me useful leads on the people he associated with when he was a radical left-wing activist in the 1940s. I discovered that, because of the revolutionary company he kept and his subsequent anti-colonial activities, the Special Branch listed him after the war, quite mistakenly, as a Trotskyist and later as an anti-British, anti-government agitator.

In order to trace his earlier life in London, I visited King’s College, where Rajaratnam had studied law at his father’s behest, to retrieve his university records. I discovered, among other things, that, having lost all interest in law during the war, he dropped out of university in 1940 to pursue his passion for writing. I also spent time sifting through British colonial papers at the Public Records Office in Kew and the British Library in London.

S. Rajaratnam outside his flat at 12 Steele Road, London, 1930s. Image reproduced from Ng, I. (2010). The Singapore Lion: A Biography of S. Rajaratnam. Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. (Call no.: RSING 327.59570092 NG).

S. Rajaratnam outside his flat at 12 Steele Road, London, 1930s. Image reproduced from Ng, I. (2010). The Singapore Lion: A Biography of S. Rajaratnam. Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. (Call no.: RSING 327.59570092 NG).All the materials I find shed new light on one or another aspect of my research. They add to the evidence – check one against another, weigh the biases, examine the angles, follow the trail. The evidence, however, is often complex and occasionally contradictory. After all, historical records themselves are not entirely neutral. Reconciling conflicting accounts and interpretations become a constant challenge.

To give a simple example: on the fateful day of 7 August 1965, how did Rajaratnam travel from Singapore to Kuala Lumpur to meet Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew where he received the shocking news of Singapore’s separation from Malaysia? It is a crucial point in my narrative as it is one of the darkest days in Rajaratnam’s political career. In his oral history interview, Rajaratnam said he travelled by plane. But there are conflicting accounts in other published sources. Then Minister for Social Affairs Othman Wok recalled driving Rajaratnam in his car to Temasek House in Kuala Lumpur. Lee himself recalled asking Rajaratnam to take a plane and not to inform anyone of his trip, but he was told years later of Othman’s recollection that they had travelled by car. Othman’s version is the one that has been used in the media. Now which version should I use, and how do I justify it?

All this places a greater demand on the skills of the writer to manage complexity and ambiguity in the narrative. However rigorous one’s research, one must be prepared for a certain degree of controversy.

I find it most satisfying when I make a new discovery during the research process, or see a new pattern, or am able to add depth to a current historical record. Few people, for example, knew until fairly recently that the young Rajaratnam found fame as a fiction writer in London, where he lived for 12 years from 1935 to 1947. He wrote short stories that met with critical acclaim, and was regarded as a leading Indian short-story writer of English works at the time – a pioneer of Malayan writing in English.

I found out that his short stories were praised by no less than E.M. Forster in a BBC broadcast on 29 April 1942.3 His work also drew the attention of George Orwell, who invited Rajaratnam to write for the weekly BBC series, “Open Letters”, to explain the different aspects of war in the form of a letter to an imaginary person. In a broadcast introducing the series on 4 August 1942, the BBC announced that “Raja Ratnam, who is well known among the new Indian writers in Great Britain, will address his letter to a Quisling”.4

My heart fluttered when, sifting through a musty cardboard box buried under piles of books in his house, I spotted some of the literary magazines containing his published works. How precious they were. With the permission of his estate, they have since been entrusted to the National Library of Singapore.

Even fewer people know that, while working as a newspaper journalist, Rajaratnam had freelanced for Radio Malaya, writing news scripts and radio plays. I discovered among his private papers the scripts for the six-part radio play, “A Nation in the Making”, which explores the controversial issues of race, language, religion and national identity. The pages were yellow, dusty and crumbling from age. At my urging and with the assistance of the NAS, the scripts are now preserved in the ISEAS library.

To restore Rajaratnam’s literary legacy, I compiled seven short stories and seven radio scripts into an anthology, The Short Stories and Radio Plays of S. Rajaratnam, which was published in 2011.

It is gratifying to see the younger generation taking a fresh interest in Rajaratnam’s fiction and adapting it for a contemporary audience. The latest effort was in 2017 by a young filmmaker, Jerrold Chong. He adapted one of Rajaratnam’s stories, “What Has to Be”, into a short animation film for the annual Singapore Writers Festival’s initiative, “Utter 2017: SingLit Unearthed”, which adapts the best of Singapore writing into film.

There were, of course, frustrating moments during the research process. For example, besides his radio plays, Rajaratnam also wrote and presented programmes on Radio Malaya on a range of other subjects, including international issues, before he stood for his first general election in May 1959. I know this because I found payment invoices for his scripts in his old Samsonite briefcase in his house. There were about 50 receipts from 17 September 1956 to 7 March 1959, detailing the titles of the scripts and his fees (between $25 and $40 for each work). Unfortunately, not a single recording of these scripts can be traced anywhere. This experience, among others, highlighted for me the heavy responsibility that our national archives bears.

Speaking out as a member of parliament, I began pressing for greater government support and funding for the work of our national archives. During the budget debate in 2006, for example, I called for major renovations to the NAS building as it was not purpose-built for a modern archives. I said: “It is to the credit of the excellent staff there that the NAS has been able to deliver good service to the public, despite its cramped workspace and tight funding”. I contrasted it with the British National Archives at Kew, which is “a modern airy building, a state-of-the-art building, with large research areas, with proper lighting for reading and research”. It also has a free museum and a cafeteria.

I repeated my calls in parliament over the following years. By 2010, I was beginning to sound like a broken record: “We should do more to develop our National Archives and ensure it has the resources to keep up with the expanding demands. Despite its importance, the archives still failed to attract interest as part of our heritage, and suffers from under-funding and neglect.” Again, I called for its building to be renovated “so that it is at least on par with the standard of our National Museum and Library”.

I am sure mine was not the only voice calling for greater national support for our archives. It is indeed good news that renovation works to the building have finally been completed and it recently opened, in time for Singapore’s bicentennial celebrations this year. But more important than the building itself, of course, are the precious resources within, both human and historical.

The challenge going forward is how the national archives can bring all its resources together to engage the public. It must be a place not only of reflection, but also of imagination. It must not become merely a venue for scholarly research, but a platform for public discussion: to help us understand the past, make sense of the present, and draw lessons for the future.

Rajaratnam could not have described my thoughts on this subject more succinctly when he wrote in an unfinished speech I found among his private papers: “Coping with the future calls for a different kind of intellectual discipline – an imaginative leap, based on past facts, on how to shape a desirable future.”

Irene Ng is a Writer-in-Residence at the ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute and a former Member of Parliament of Singapore (2001–2015). She was a senior political correspondent with The Straits Times before entering politics. She has written a biography of S. Rajaratnam and is working on a second volume.

Irene Ng is a Writer-in-Residence at the ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute and a former Member of Parliament of Singapore (2001–2015). She was a senior political correspondent with The Straits Times before entering politics. She has written a biography of S. Rajaratnam and is working on a second volume.

NOTES

-

Ng, I. (2010). The Singapore lion: A biography of S. Rajaratnam. Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. (Call no.: RSING 327.59570092 NG) ↩

-

Ng, I, (2011). The short stories and radio plays of S. Rajaratnam. Singapore: Epigram Books. (Call no.: RSING S823 RAJ) ↩

-

Lago, M., Hughes, L.K., & Walls, E.M. (Eds.) (2008). The BBC talks of E.M. Forster, 1929–1960: A selected edition. Columbia, MO: University of Missouri Press. (Not available in NLB holdings) ↩

-

Orwell, O. (2001). All propaganda is lies, 1941–1942 (p. 446). London: Secker & Warburg. (Call no.: 828.91209 ORW). The book compiles George Orwell’s letters and commentaries related to his radio programmes. [Note: Quisling, named after Norwegian politician Vidkun Quisling who assisted Nazi Germany to conquer his own country during World War II, is a term used to describe traitors and collaborators.] ↩