From Lat Pau to Zaobao: A History of Chinese Newspapers

Chinese newspapers have been published in Singapore since the 19th century. Lee Meiyu looks at how they have evolved and examines their impact on the Chinese community here.

The Chinese newspaper industry in Singapore has a colourful and varied history enriched by a large, revolving cast of missionaries, reformists, revolutionaries, businessmen, writers and the government. Since the first Chinese newspaper was published in Singapore in 1837, over 160 newspapers have come and gone.1 Some of them played an important role in disseminating information to the people as well as shaping politics, society, culture and literature in Singapore.

The First Chinese Newspaper in Singapore

Singapore’s first Chinese newspaper was a periodical titled Eastern Western Monthly Magazine (东西洋考每月统记传). It was originally published in Canton (now Guangzhou), China, on 1 August 1833 by the German missionary Karl Friedrich August Gützlaff. He started the magazine with the aim of making “the Chinese acquainted with [the] arts, sciences and principles of [the Westerners]… to show that [the Westerners] are not indeed ‘Barbarians’; and… convince the Chinese that they have still very much to learn… of the relation in which foreigners stand to the native authorities, the Editor endeavoured to conciliate their friendship”.2

Gützlaff (who adopted the Chinese name Guo Shilie [郭士立 or 郭实腊 or 郭实猎] and a Chinese pen name Ai Han Zhe [爱汉者], which means “one who loves the Chinese”) was the first Lutheran missionary to China, and a translator and civil servant. Due to his busy schedule, Gützlaff had to stop the printing of Eastern Western Monthly Magazine in May 1834. Readers had to make do with reprints and with occasional new issues published in 1835. In 1837, the magazine operations relocated to Singapore – possibly due to the increasingly strained Sino-British relations – and continued as the organ of the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge in China, which had been founded by Gützlaff in Canton.

The magazine restarted in earnest in Singapore under the editorship of Gützlaff, John Robert Morrison, the son of Robert Morrison (the London Missionary Society’s first missionary to China and the man who translated the Bible into Chinese) and, most likely, the English Protestant missionary Walter Henry Medhurst, who was also involved in the Chinese translation of the Bible.3

Although published by missionaries, the Eastern Western Monthly Magazine was a largely secular periodical that covered the news and included articles on history, geography, science, commerce and literature. Religion only made the occasional appearance in the form of articles on Western culture in comparison with its Eastern counterpart. Its news section mostly carried translated articles from foreign newspapers and, in later issues, news from the Peking Gazette.4 The magazine ceased publication in 1838.5

Singapore’s First Chinese Daily

A little over four decades after the demise of Eastern Western Monthly Magazine, Lat Pau,6 the first Chinese daily in Singapore (and Southeast Asia), made its debut. Lat Pau was founded in December 1881 by See Ewe Lay (薛有礼), a prominent Melaka-born Straits Chinese who moved to Singapore to join the Hong Kong and Shanghai Bank as a comprador.

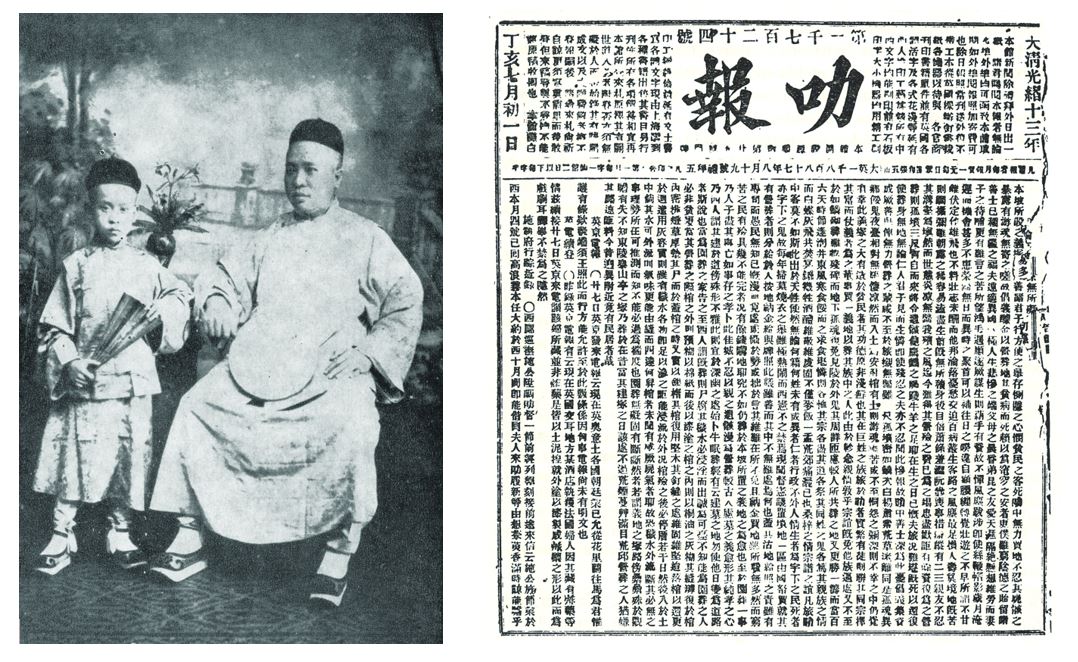

(Right) The earliest extant copy of Lat Pau dated 19 August 1887. This front page with the masthead features an editorial and three news items. Image reproduced from Chen, M.H. (1967). The Early Chinese Newspapers of Singapore, 1881–1912 (p. 30). Singapore: University of Malaya Press. (Call no.: RSING 079.5702 CHE).

Lat Pau, or Le Bao (叻报), derived its name from Se-lat-po or Shi Le Po (石 叻 坡), the Hokkien and Cantonese names for Singapore. The names, in turn, came from the Malay word selat, which means “straits”. One of the paper’s earliest editors was Yeh Chi-yun (叶季允) from Hong Kong.7 Yeh worked for Lat Pau for 40 years, penning numerous editorials under his pen name Xing E Sheng (惺噩生).

The staff of Lat Pau believed in “recording whatever is heard” (有闻必录), which meant that many of the reports were based on hearsay, with little or no effort taken to verify facts. According to Yeh, “The people were not enlightened, hence very narrow in their outlook. They were not interested in the affairs of the world but only interested in their own petty amusement. The newspapers… presented their news items only to catch the eye. Therefore the newspapers contained a hotch-potch of serious events and frivolous matters.”8

The paper’s editorial was published on the front page, with extracts from the Peking Gazette on subsequent pages. General news consisted of reports reproduced from Hong Kong and Shanghai newspapers, translations from local English newspapers as well as stories based on hearsay or news provided by agents living in other parts of Southeast Asia. The remaining pages were devoted to business-related advertisements and notices, including those by the British and Dutch colonial governments.9

The editorials of Lat Pau tended to be conservative when it came to Chinese politics, supporting the Qing government on anything related to China. It took a pro-Chinese stand when the interests of the Chinese community in Singapore were affected by government policies.

In the early years, Chinese newspapers in Singapore had a very small circulation because of low literacy rates among Chinese migrants here. By 1900, Lat Pau’s circulation had reached 550, up from 350 in 1883.10 Subscriptions formed an insignificant portion of the paper’s income. Instead, the company derived its revenue from advertising, with the printing and sale of books helping to sustain business as Lat Pau was also a bookseller and ran a commercial printing press.11

Lat Pau was profitable in the early years and its subscriptions increased. However, after Yeh died in 1921, there were frequent changes to its editorial board. The English-educated members of the See family who took over the management also found it difficult to run the Chinese newspaper. Because of these factors, as well as increasing competition from other Chinese newspapers, Lat Pau finally ceased publication in 1932.12 The earliest extant copy of Lat Pau is dated 19 August 1887.13

Growing Political Awareness

In 1898, Thien Nan Shin Pao (天南新报) was founded by Khoo Seok Wan (邱菽园), Chinese literary pioneer in Singapore who was also the paper’s chief writer. After seeing the Qing government humiliated by Western powers, Khoo became an advocate for reform and enlightenment in China. He established Thien Nan Shin Pao for “the expression of progressive ideas and the elucidation of the methods which have lifted up the European nations from the empiricism and follies of the past”.14

The newspaper provided extensive coverage of the political and social reforms taking place in China as well as local news. In addition, it supported progressive ideas such as education for girls. Although short-lived (the newspaper folded in 1905), Thien Nan Shin Pao is significant because it is the first example of a local Chinese newspaper that took an ideological position and actively advocated for a cause – in this case Chinese nationalism and reform.15

Reformists Versus Revolutionaries

Following the failure of the Hundred Days’ Reform movement,16 reformist leader Kang Youwei (康有为) fled China and arrived in Singapore in 1900 where he sought to build the reform movement with the aid of funds and supporters here. In August 1905, Sun Yat-sen established the Tong Meng Hui (同盟会; Chinese Revolutionary Alliance) in Tokyo. This was an underground resistance move ment aimed at gathering support for the Chinese revolutionary cause and to raise funds for its activities. In the same year,17 the Singapore branch of Tong Meng Hui was founded and became the centre of revolutionary activities in Southeast Asia.

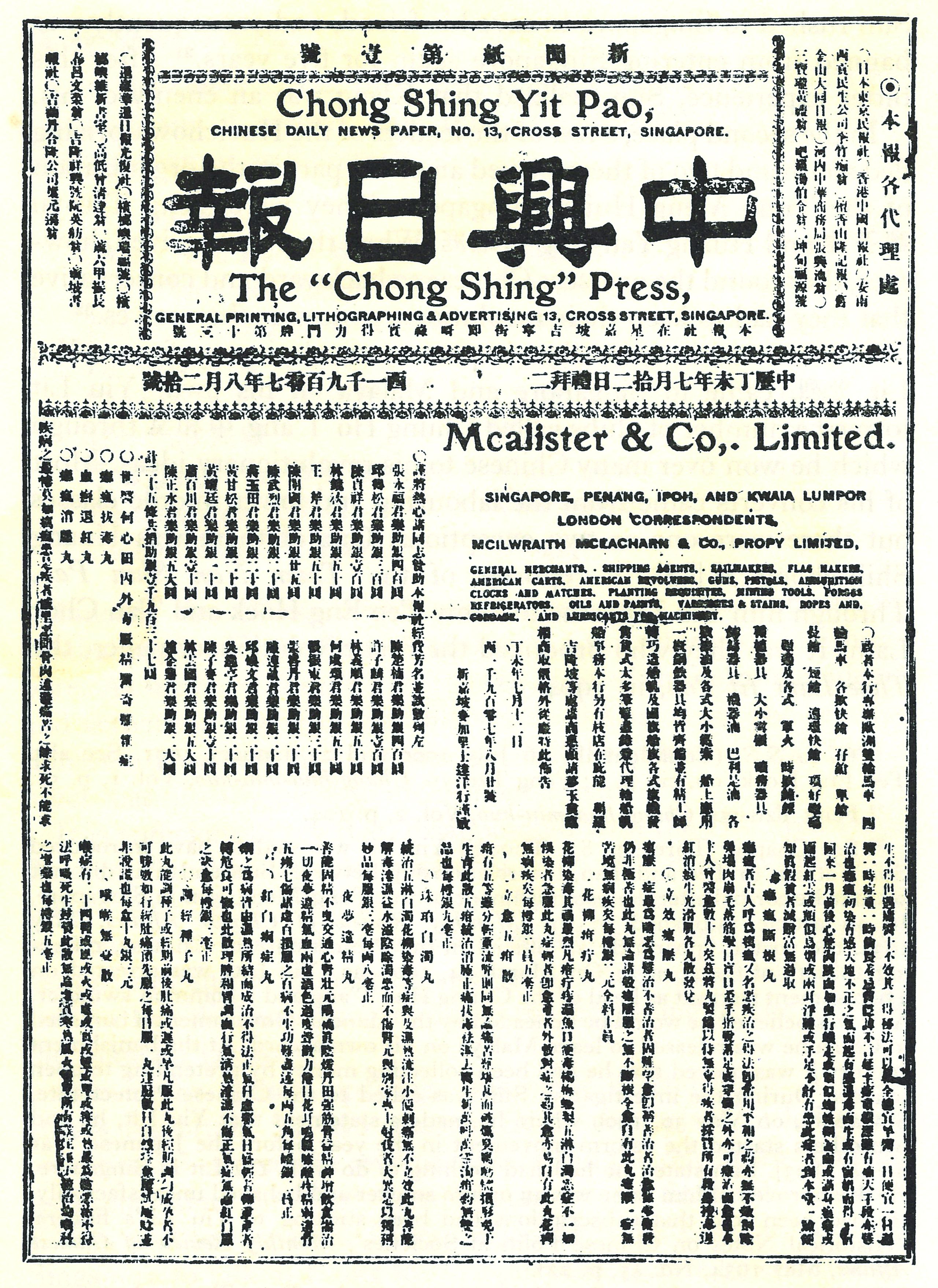

Singapore became a battleground as reformists and revolutionaries made use of the local Chinese newspapers to further their cause and denigrate the opposition.18 The most intense battle was fought between the reform-minded Union Times (南洋总汇报) and Chong Shing Yit Pao (中兴日报), which was set up by revolutionaries.19

Union Times was founded in 1906 by two supporters of the revolutionary movement, Teo Eng Hock and Tan Chor Lam,20 but it came under the control of reformists shortly after and became their mouthpiece in Singapore and Southeast Asia. In response, the revolutionaries set up Chong Shing Yit Pao in 1907 to combat the influence of Union Times.

Editorials in Chong Shing Yit Pao ridiculed the belief held by the reformists that a constitution would work under the Qing government, while Union Times argued that revolution was impracticable and branded the revolutionaries as rebels and hooligans causing civil strife in China. Articles written by Kang and Sun can be found in the respective newspapers.21 Both newspapers also presented the news in a way that supported their editorial positions.

It was in the literary section, however, that the debates were the most exciting. Here, the writers unleashed their creativity and literary skills using commentaries, short stories, dramatic dialogues, Cantonese ballads, poetry and humour22 to persuade, argue, refute, condemn and even slander the other party. They were not above calling each other names like “fleas”, “mad dogs” and “prostitutes”. These altercations sometimes ended up in court as the newspapers sued each other for libel.23

The fierce rivalry between the two newspapers, however, sparked an increased awareness in world affairs and an interest in newspapers among the masses. The pool of foreign journalistic talent in Singapore also raised the bar of the Chinese newspaper industry.

Due to financial difficulties, Chong Shing Yit Pao folded in 1910 and did not witness the fall of the Qing dynasty a year later. Union Times, which had a more established support network, ceased publication in 1948.24

Modernisation and the War Years

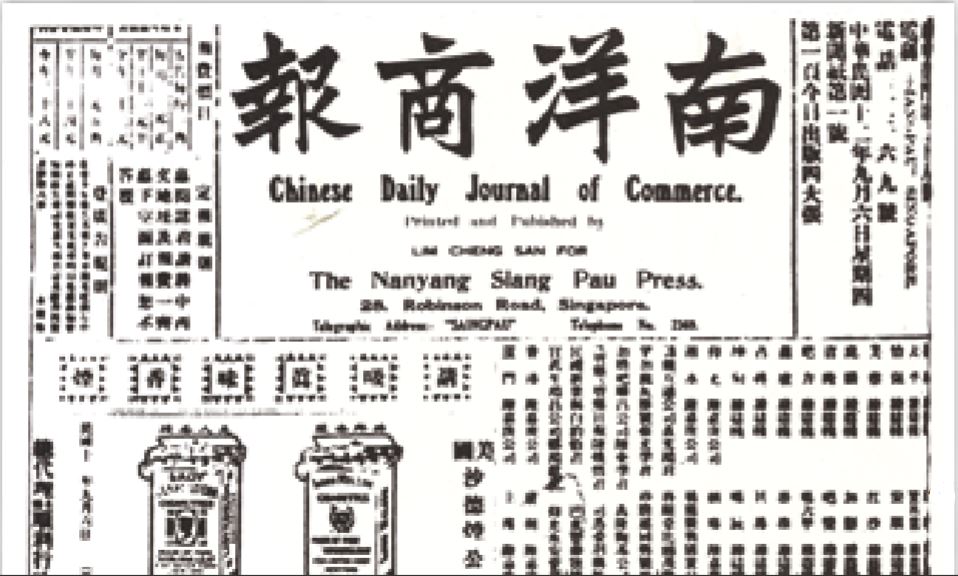

Two important newspapers appeared in the 1920s: Nanyang Siang Pau (南洋商报) founded by “Rubber and Pineapple King” Tan Kah Kee in 1923 and Sin Chew Jit Poh (星洲日报) by Aw Boon Haw of Tiger Balm in 1929. Both newspapers played an important role in the modernisation of the industry.25

(Right) Portrait of “Tiger Balm King” Aw Boon Haw, who founded Sin Chew Jit Poh in 1929. Image reproduced from Who’s Who in China (4th edition) (1931) (p. 497). Shanghai: The China Weekly Review.

Nanyang Siang Pau was set up as an advertising platform for Tan’s rubber products. It was a business newspaper that also aimed to promote education. Likewise, Aw used Sin Chew Jit Poh to publicise the Chinese medicinal products under his Tiger Balm brand.26 He also hoped to make readers better informed and to encourage them to invest in China’s economy.27

In the initial issues, news coverage in both newspapers was limited and tended to focus on events in China. Instead the papers were filled with advertisements. However, Tan and Aw spared no efforts to recruit talent, and the quality of the content soon improved. News coverage was expanded and became more organised. Layout was also improved to make for easier reading. Segments focusing on commerce, sports, culture and education were added to provide greater variety.

Well-known writers and journalists in China and Singapore such as Fu Wumen, Khoo Seok Wan, Yu Dafu and Hu Yuzhi were also hired by the newspapers. Their editorials and fukan (副刊; literary supplements) were well written, perceptive and informative.28

With substantial financial backing and the availability of experienced staff, the two newspapers soon became the leading Chinese dailies in Singapore. Both invested heavily in infrastructure and built up their distribution network. Modern printing machines were introduced into their operations in the 1920s and 1930s. They also successfully expanded into the region by establishing an extensive network of agencies and sub-distributors. Additionally, the newspapers tapped on local correspondents in various countries to submit news and stories via cable.29

Following the Japanese invasion of Manchuria in 1931, Nanyang Siang Pau began publishing on Sundays to deliver the latest news about the war. This edition, later renamed the “Sunday Edition”, first came out on 20 December 1931. This marked the first time that a local newspaper was published on a Sunday. Other newspapers, including non-Chinese ones, soon followed with their own Sunday edition. Rival Sin Chew Jit Poh started its “Sunday Special Supplement” five months later.30

The fall of Singapore to the Japanese in February 1942, however, put a halt to further newspaper developments. During the Japanese Occupation, many Chinese journalists, writers and editors ended up being killed during Operation Sook Ching31 or had to flee Singapore because of their anti-Japanese writings before the Occupation. All local newspapers were taken over by the Propaganda Department and later by Domei News Agency, the official news agency of the Empire of Japan.

Facilities at Nanyang Siang Pau and Sin Chew Jit Poh were seized, and the office of Sin Chew Jit Poh on Robinson Road was used to publish the Chinese newspaper Zhaonan Ribao (昭南日报), a wartime propaganda channel for the Japanese government. First published on 21 February 1942, Zhaonan Ribao was the Chinese edition of The Syonan Shimbun, the English-language newspaper produced by the Japanese to replace The Straits Times.

One defining feature of Zhaonan Ribao was its articles about the Overseas Chinese Association, an organisation set up to mediate between the Japanese government and the local Chinese community. The newspaper also carried more content relating to Japanese culture, values and history in a section called “Chao Yang” (朝阳).32

Post-war Developments

Both Nanyang Siang Pau and Sin Chew Jit Poh resumed publication in September 1945, almost immediately after the Japanese surrendered. The readership and market of these two newspapers expanded in the post-war years and, in the 1950s, both papers even purchased aeroplanes to deliver copies to their subscribers in the region.

This post-war period also saw the streamlining of work processes at the two newspapers: administrative duties were hived off from editorial work, and new departments such as public relations and operations were established. Both papers also moved with the times by using simplified Chinese characters and horizontal typesetting in the 1970s, and incorporating new technology in the 1980s.33

It was not all smooth sailing though. In 1971, the arrest of four senior staff from Nanyang Siang Pau sent shockwaves through the industry. The government accused the newspaper of jeopardising the internal security and stability of Singapore. The relationship between the newspaper and the government became tense, with both sides releasing statements denying each other’s claims. The four people were detained for periods ranging between seven and 29 months.34 In 1973, another senior executive was arrested under the Internal Security Act. He was only released five years later.

In 1974, the Newspaper and Printing Presses Act came into force. Under this legislation, all newspaper publishing companies had to be converted into public companies. The company that owned Sin Chew Jit Poh was reorganised into a public entity under the name Sin Chew Jit Poh (Singapore) Limited, while Nanyang Siang Pau became owned by Nanyang Press Singapore Limited. The act also required the companies to issue both ordinary shares and management shares, which they did in 1977.35

Perhaps the most important milestone in the history of the industry was the merger of the two rival dailies in 1983. Due to potential falling readership as a result of English being taught as the first language in schools and mother tongues as the second, the two Chinese dailies decided to pool resources and end their decades-long rivalry. The merger led to the formation of Singapore News and Publications Limited, which produced the morning paper Lianhe Zaobao (联 合早报) and the evening paper Lianhe Wanbao (联合晚报).

In 1984, the three newspaper companies in Singapore – Singapore News and Publications Limited, The Straits Times Press Limited and Times Publishing Berhad – merged to form Singapore Press Holdings Limited (SPH). The publishing conglomerate currently owns all the major newspapers produced in Singapore.36

Today, SPH publishes 17 newspapers titles in the four official languages (English, Chinese, Malay and Tamil). The main Chinese daily, Lianhe Zaobao, has a print and digital circulation of 212,200, with subscribers from Singapore as well as Indonesia, Brunei, Hong Kong, Vietnam, Beijing and Shanghai. In 1995, as part of its digital transformation, Lianhe Zaobao began publishing an online edition to enlarge its subscriber pool.37

In this digital age, however, subscriptions to physical newspapers have been steadily decreasing. On 18 October 2019, SPH reported that the total circulation of all print newspapers in its stable had declined by 7.3 percent compared with the previous year. On the contrary, its digital business showed healthy growth with Chinese newspapers attracting more than 10,000 signs-up, of which three-quarters were new subscribers.

Moving forward, SPH has announced that it will focus on the digital transformation of its core media business and intensify efforts to make content available across different platforms. It remains to be seen, however, if Chinese newspapers in Singapore will continue to evolve and transform with the same innovative spirit and fervour that their predecessors did.38

FUKAN – THE CRADLE OF SINGAPORE CHINESE LITERATURE

In 1907, Chinese daily Lat Pau introduced a supplement known as fu zhang (附张; which literally means “attached sheet”) in which folksongs and popular tales along with other miscellaneous articles were featured.39

Other Chinese newspapers followed suit and produced their own supplements, now called fukan (副刊). One of the most important fukan published was </i>Xin Guo Min Za Zhi</i> (新国民杂志), the supplement to </i>Sin Kuo Min Jit Poh</i> (新国民日报), which was founded in 1919. This supplement was a milestone in the history of Singapore Chinese literature as it introduced modern Chinese literature inspired by the New Culture Movement40 in China to local readers.

|In 1925, Nan Feng (南风) was published by Sin Kuo Min Jit Poh while Xing Guang (星光) was published by Lat Pau. These supplements helped define Singapore Chinese literature and establish its future direction of growth.

Other important fukan that contributed to the development of Chinese literature in Singapore were Huang Dao (荒岛) (1927) and Lu Yi (绿漪) (1927) by Sin Kuo Min Jit Poh; Ye Lin(椰林) (1928) by Lat Pau; Hong Huang (洪荒) (1927), Wen Yi San Ri Kan (文艺三日刊) (1929) and Shi Sheng (狮声) (1933) by Nanyang Siang Pau; and Ye Pa (野葩) (1930) and Chen Xing (晨星) (1937) by Sin Chew Jit Poh.

Fans of Chinese sword-fighting, or wuxia, novels would be familiar with Linghu Chong (令狐冲), the honourable, happy-go-lucky swordsman with a weakness for alcohol. He is the protagonist in Xiao Ao Jianghu (笑傲江湖), a story written by the Hong Kong writer Jin Yong (金庸; also known as Louis Cha).

Xiao Ao Jianghu (笑傲江湖) by the Hong Kong writer Jin Yong (金庸; also known as Louis Cha) was first serialised in the inaugural issue of Shin Min Daily News on 18 March 1967. Image reproduced from 金庸 [Jin Yong]. (1996).《笑傲江湖》[The Wandering Swordsman]. 新加坡: 明河社出版有限公司.

Xiao Ao Jianghu (笑傲江湖) by the Hong Kong writer Jin Yong (金庸; also known as Louis Cha) was first serialised in the inaugural issue of Shin Min Daily News on 18 March 1967. Image reproduced from 金庸 [Jin Yong]. (1996).《笑傲江湖》[The Wandering Swordsman]. 新加坡: 明河社出版有限公司.

Known in English under various titles such as The Wandering Swordsman and The Smiling, Proud Wanderer, the novel is so popular that it has been adapted for the stage, television, the big screen, comic books and even video games. To attract readers, the novel was first serialised in the inaugural issue of Shin Min Daily News (新民日报) on 18 March 1967, a local newspaper started by Cha and the founder of Axe Brand Universal Oil, Leong Yun Chee.

This was even before the novel was published in the Hong Kong newspaper Ming Pao (民报), which was also founded by Cha. Serialisation of his other novels in Shin Min soon followed.

The entrance of Shin Min Daily News livened up the Chinese newspaper publishing scene in Singapore with its focus on the world of entertainment. The daily became an instant hit, thanks to its lottery results, sword-fighting novels, exclusive entertainment news and horse racing tips.

In 1983, Shin Min Daily News became a subsidiary company of The Straits Times Press Limited. One year later, in 1984, the paper became part of Singapore Press Holdings group.

THE RISE AND FALL OF CHINESE TABLOIDS

Chinese tabloids first appeared and flourished in Singapore in the 1920s, providing readers with a different form of entertainment compared to the dailies. Known as xiao bao (小报), these tabloids were usually published once every two to three days and were much thinner than the dailies.

Xin Li Bao (新力报) reporting on the opening of the latest nightclub in Singapore in December 1950. Xin Li Bao, 29 December 1950 (issue 16).

Xin Li Bao (新力报) reporting on the opening of the latest nightclub in Singapore in December 1950. Xin Li Bao, 29 December 1950 (issue 16).

The first Chinese tabloid, Xiao Xian Zhong (消闲钟), was published in Singapore in 1925. It featured mostly entertainment news, while other tabloids focused on topics such as photography, commerce, literature, education and politics.

The late 1940s and the 1950s marked another golden age for Chinese tabloids in Singapore. Ye Deng Bao (夜灯报) and Xin Li Bao (新力报) were the two most popular tabloids during that period. Chinese tabloids were mainly known for their frivolous reporting of entertainment news on the latest movies, celebrity gossip, getai (live stage performances) and popular bar hostesses. They also prided themselves on their ability to get the inside scoop on these subjects and regularly covered titillating topics like sensational crime and prostitution.

Some tabloids resorted to pornography to increase their readership in the highly competitive market. On the basis that these tabloids were promoting “yellow culture”,41 the government banned a number of such publications or revoked the printing licences of the companies in the 1960s.

The author wishes to thank Mr Lee Ching Seng for reviewing the essay. Past issues of Chinese newspapers can be accessed via NewspaperSG – a searchable, online archive of local newspapers – and also from the microfilm collection at level 11 of the Lee Kong Chian Reference Library.

Lee Meiyu is a Librarian with the National Library, Singapore, and works with the Singapore & Southeast Asian Collection. Her research interests include Singapore’s Chinese community. She is co-author of Money by Mail to China: Dreams and Struggles of Early Migrants (2012) and Roots: Tracing Family Histories – a Resource Guide (2013).

Lee Meiyu is a Librarian with the National Library, Singapore, and works with the Singapore & Southeast Asian Collection. Her research interests include Singapore’s Chinese community. She is co-author of Money by Mail to China: Dreams and Struggles of Early Migrants (2012) and Roots: Tracing Family Histories – a Resource Guide (2013).

Notes

-

This essay is unable to cover the history of all Chinese newspapers published in Singapore since the 19th century. Only selective ones are mentioned. It is estimated that there were about 164 Chinese newspaper titles published between 1881 and 1959. See 王慷鼎 [Wang, K.D.]. (2014). 《王慷鼎论文集》[A compilation of articles by Wong Hong Teng] (p. 253). 新加坡: 南洋学会. (Call no.: Chinese RSING 079.5957 WKD) ↩

-

Zhang, X.T. (2007). The origins of the modern Chinese press: The influence of the Protestant missionary press in late Qing China (p. 39). New York: Routledge. (Call no.: R 079.51 ZHA) ↩

-

S.J. Huang and J.G. Lutz in the sources stated below indicated that the 1835 issues were printed in Singapore, while R.S. Britton and X.T. Zhang mentioned that these were printed in Canton. 爱汉者等编 [Ai, H.Z. et al.]; 黄时鉴整理 [Huang, S.J. compiled]. (1997).《东西洋考每月统记传》 (Eastern Western Monthly Magazine) (pp. 4, 7, 10–12). 北京: 中华书局. (Call no.: Chinese R 059.951 EAS); Lutz, J.G. (2008). Opening China: Karl F.A. Gützlaff and Sino-Western relations, 1827–1852 (pp. 3–4). Michigan: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. (Call no.: RSEA 266.0092 LUT); Britton, R.S. (1933). The Chinese periodical press, 1800–1912 (pp. 22–24). Shanghai: Kelly & Walsh. (Call no.: RCLOS 079.51 BRI); Zhang, 2007, pp. 40–41. ↩

-

Also known as Di Bao (邸报), these were official publications by the Chinese imperial court to circulate news on imperial decrees and official memoranda among the ruling class. Di Bao was an early form of a Chinese news-related publication before modern journalism took root in China. ↩

-

Zhang, 2007, pp. 3, 40; Zhao, Y.Z. & Sun, P. (2018). A history of journalism and communication in China (pp. 13–14, 24). New York: Routledge. (Call no. R 079.51 ZHA). Compiling the magazine issues found in the holdings of Harvard-Yenching Library, The British Library, Yale University Library and Cornell University Library, S.J. Huang indicated that the last available issue was printed in 1838 (p. 9). However, J.G. Lutz stated that the last issue of the magazine was dated 13 February 1839 (p. 182). She did not indicate the source of her information. ↩

-

Chen, M.H. (1967). The early Chinese newspapers of Singapore, 1881–1912 (p. 24). Singapore: University of Malaya Press. (Call no.: RSING 079.5702 CHE); Yap, K.S. (1996). The press in Malaysia & Singapore (1806–1996) (pp. 1–3). Kuala Lumpur: Yap Koon See. (Call no.: RSING 079.595 YKS) ↩

-

Chen, 1976, pp. 31–32; Wong Hong Teng mentioned in his article, “The confirmation of Lat Pau’s first date of issue”(《叻报》创刊日期正式确定), published in the Sin Chew Jit Poh on 24 May 1982 that he had located two notices on 9 and 10 December 1881 in The Singapore Daily Times which mentioned that Lat Pau would be published under the editorship of T. Chong Eng. However, Wong was unable to ascertain whether T. Chong Eng, the editor of Lat Pau’s first issue, was Yeh Chi-yun. ↩

-

The earlier issues of the newspaper are no longer available. The 19 August 1887 copy of Lat Pau has been digitised and can be read online at the NUS Libraries website: lib.nus.edu.sg/lebao/index.html. ↩

-

The Hundred Days’ Reform was a failed 103-day reform movement undertaken by Emperor Guangxu and his supporters in 1898. Accepting suggestions made by Kang Youwei, Emperor Guangxu enacted a series of reforms aimed at making sweeping social and institutional changes. The movement failed when the opposing conservative forces initiated a coup that led to the emperor’s house arrest. ↩

-

Academic sources list the year as 1906. However, personal recollections by the three leading revolutionaries in Singapore, Teo Eng Hock, Tan Chor Lam and Lim Nee Soon, state the year as 1905. See Nanyang and founding of the Republic (《南洋与创立民国》), Wan Qing Yuan and the 1911 Revolution (《晚晴园与中国革命史略》) and A record of the Tong Meng Hui in Singapore (《星洲同盟会录》). See “When was the Singapore branch of Tong Meng Hui established?” (星洲同盟会到底何时成立) in Lianhe Zaobao (6 October 2011) for a discussion of the discrepancies. ↩

-

Chen, 1967, pp. 43, 53; 彭剑 [Peng, J.]. (2011).《清季宪政大辩论: 〈中兴日报〉与〈南洋总汇新报〉论战研究》 [Debates on constitutionalism in late Qing: The arguments between Union Times and Chong Shing Yit Pao] (pp. 19—20). 武汉: 华中师范大学出版社. (Call no.: Chinese R 951.07 PJ) ↩

-

Sources referred to in this article mention two dates: late 1905 or early 1906. Unfortunately, as the early issues of Union Times are lost, there is no way to ascertain the correct year. ↩

-

Chen, 1967, pp. 86, 89, 94, 97; See J. Peng for a detailed list of articles and names of main writers (pp. 27–39). ↩

-

See J. Peng (2011) for a detailed list of the literary articles (pp. 49–55). ↩

-

Chen, 1967, pp. 100–104; Yen, C.H. (1976). The Overseas Chinese and the 1911 revolution (p. 188). Kuala Lumpur: Oxford University Press. (Call no.: RSING 301.451951095957 YEN); Song, O.S. (1984). One hundred years’ history of the Chinese in Singapore (p. 441). Singapore: Oxford University Press. (Call no.: RSING 959.57 SON-[HIS]) ↩

-

郑文辉 [Tay, B.H.]. (1973).《新加坡华文报业史, 1881-1972》 [History of Chinese newspapers in Singapore, 1881-1972] (pp. 36, 38). 新加坡: 新马出版印刷公司.(Call no.: Chinese RCLOS 079.5957 CWH); Chen, 1967, p. 105–107, 110; Yen, 1976, p. 202. ↩

-

Lim, J.K. (ed.) (1993). Our 70 years: History of leading Chinese newspapers in Singapore (pp. 82-89). Singapore: Chinese Newspapers Division, Singapore Press Holdings.(Call no.: RSING 079.5957 OUR) ↩

-

As the two leading Chinese dailies in Singapore, Nanyang Siang Pau and Sin Chew Jit Poh aggressively competed for readers. Their rivalry continued right up to the years before their merger in 1983. See “The history of two rivals” in The Straits Times (22 April 1982). ↩

-

Following the fall of Singapore on 15 February 1942, Chinese males between 18 and 50 years of age were ordered to report at designated centres for mass screening. Many of these ethnic Chinese were then rounded up and taken to deserted spots to be summarily executed. This came to be known as Operation Sook Ching (the Chinese term means “purge through cleansing”). It is not known exactly how many people died; the official estimates given by the Japanese is 5,000, but the actual number is believed to be 8−10 times higher. ↩

-

Zhaonan Ribao, 21 February 1942–31 May 1944. ↩

-

George, C. (2012). Freedom from the press: Journalism and state power in Singapore (pp. 30– 31). Singapore: NUS Press. (Call no.: RSING 079.5957 GEO); Lim, 1993, pp. 85, 88. ↩

-

George, 2012, p. 127; 崔贵强 [Chui, K.C.]. (2002). 《 东南亚华文日报现状之研究》[A study of the current Chinese dailies in Southeast Asia] (p. 15).新加坡: 华裔馆. (Call no.: Chinese RSING 079.59 CGQ); Peng, W.B. (2005).《东南亚华文报纸研究》[A study of Chinese newspapers in Southeast Asia] (p. 36). 北京: 社会科学文献出版社. (Call no.: Chinese RSEA 079.59 PWB) ↩

-

Singapore Press Holdings Limited. (2019). Homepage. Retrieved from Singapore Press Holdings website; Singapore Press Holdings Limited. (2019). Lianhe Zaobao/Lianhe Zaobao Sunday. Retrieved from Singapore Press Holdings website; Chui, 2002, pp. 17, 23, 33. ↩

-

SPH to shed 130 jobs to rein in costs. (2019, October 18). The Straits Times, p. C2. Retrieved from The Straits Times website. ↩

-

Some sources state 1906, which is likely a misinterpretation of Tan Yeok Seong’s statement in The First Newsman in Nanyang (《南洋第一报人》). Tan provided the date as “the 3rd day of the 12th month in the 32nd year of Emperor Guangxu’s reign”. This would be 16 January 1907 in the Gregorian calendar. ↩

-

The New Culture Movement in China, which took place between the 1910s and 1920s, criticised traditional Chinese culture, blaming it for the country’s subordinate position in the world. Intellectuals supporting the movement pushed for the adoption of Western notions of science and democracy, and these became the focus of their writings. The movement also called for vernacular literature to replace classical literature, which had become unintelligible to the masses. ↩

-

The Singapore government launched a campaign against “yellow culture” on 8 June 1959 to clamp down on various aspects of Western culture that were seen as promoting a decadent lifestyle. The term “yellow culture” is a direct translation of the Chinese phrase huangse wenhua (黄色文化), which refers to undesirable behaviour such as gambling, opiumsmoking, pornography, prostitution, corruption and nepotism that plagued China in the 19th century. ↩