Snakes, Tigers and Cannibals: Ida Pfeiffer’s Travels in Southeast Asia

Travelling alone across Southeast Asia in the 19th century, Ida Pfeiffer encountered human heads put out to dry and faced off angry cannibals. John van Wyhe recounts the adventures of this remarkable woman.

The name Ida Pfeiffer (1797–1858) is largely unknown today, but in the mid-19th century, she was one of the most famous women in the world. Starting in her mid-40s, this Viennese mother of two embarked on five major expeditions, two of which involved circumnavigating the globe. She accomplished all this while travelling as an unchaperoned woman, a notion that was almost unheard of in those days.

During the course of her journeys, Pfeiffer visited Singapore twice: in 1847 and in 1851. Thanks to her, we have a glimpse of Singapore’s natural environment during the period as well as snapshots of daily life on the island.

A Tomboy Who Grew Up

Ida Laura Reyer was born into a wealthy merchant family in Vienna in 1797. As a child, she was a stubborn and headstrong tomboy who frequently harboured grand ambitions, such as travelling to exotic far-off lands and exploring the world.

She married a lawyer named Dr Mark Anton Pfeiffer in 1820. The union, which produced two sons, was not a happy one though. In 1835, she separated from her husband, although they remained on good terms. By 1842, her sons were gainfully employed and independent. With her motherly duties completed, Ida Pfeiffer, now aged 45, was finally free to do what she had always dreamed of – to see the world.

Pfeiffer’s career as a travel writer began after her first journey, which was to the Middle East in 1842 when she visited Constantinople, Jerusalem and Cairo. Her travel journal caught the attention of a publisher; in 1844, he turned it into her first book, Journey of a Viennese Lady to the Holy Land, which became a bestseller.

This bankrolled her next adventure to Iceland in 1845. The country had a reputation as both impossibly remote and a land of dramatic natural wonders, including volcanoes and geysers. Her adventures led to her second book in 1846 titled Journey to the Scandinavian North and the Island of Iceland.

First Visit to Singapore (1847)

Not long after her Nordic adventure, Pfeiffer set off on her greatest voyage yet: a circumnavigation of the entire globe. She would be the first woman ever to do so alone.

In 1846, Pfeiffer boarded a sailing ship to Brazil. During a forest excursion, she and a male companion were attacked by a robber with a large knife that left both of them injured. She continued on her journey to Chile and then Tahiti before arriving in China in 1847, where her appearance as an unaccompanied European woman on the streets nearly caused riots. In September 1847, she boarded the monthly P&O steamer from Hong Kong to Singapore.

The 10-day trip was not a happy one. She wrote: “I have made many voyages on board steam ships and always paid second fare, never did I pay so high a price for such wretched and detestable treatment. In all my life I was never so cheated.”1

The names of arriving and departing first-class P&O passengers were announced in the newspapers. The Singapore Free Press must have assumed that the Austrian lady, who disembarked with two other passengers in first class, also travelled in the same class. Respectable people didn’t travel any other way and so they reported the arrival of “Mrs Pfeiffer” from Hong Kong.2 However, Pfeiffer had very little money and had actually travelled second class, even though the men at the ticketing office in Hong Kong commented that “respectable” people did not travel in steerage.

Upon her arrival in Singapore, Pfeiffer made her way to the office of German shipping and trading agent Behn, Meyer & Co., which had been established by Theodor August Behn and Valentin Lorenz Meyer in 1840. She had brought letters of introduction with her.

Behn’s wife Caroline was the first German lady Pfeiffer had met since Brazil and the two immediately hit it off. In fact, Frau Behn “would not hear of my lodging in a hotel; I was immediately installed as a member of her own amiable family in their comfortable bungalow on Mount Sophia, not far from Government hill”.3

Apart from the incessant heat and inescapable humidity, Pfeiffer found life very pleasant in Singapore. There was very little crime and the infrastructure was good. Pfeiffer wrote:

“… the whole island offers the most enchanting sight… the luxuriant verdancy, the neat houses of the Europeans in the midst of beautiful gardens, the plantations of the most precious spices, the elegant areca and feathered palms, with their slim stems shooting up to a height of a hundred feet, and spreading out into the thick feather-like tuft of fresh green, by which they are distinguished from every other kind of palms, and, lastly, the jungle in the background, compose a most beautiful landscape… The whole island is intersected with excellent roads, of which those skirting the sea-shore are the most frequented, and where handsome carriages and horses from New Holland, and even from England, are to be seen.”4

Paddling up the Kallang River

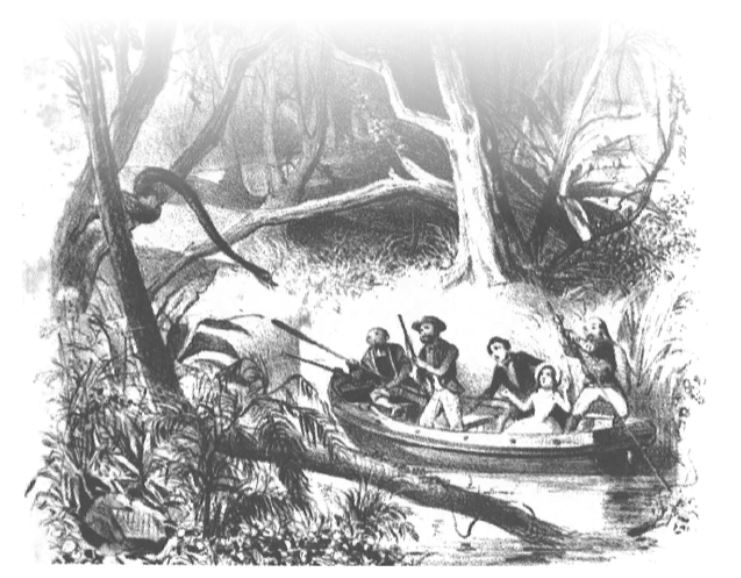

During her time in Singapore, Herr Behn and Herr Meyer took Pfeiffer on a hunting excursion where they hoped, rather optimistically, to bag a tiger or at least a wild boar. They first paddled up the narrow Kallang River. It was here that Pfeiffer encountered the vibrant exuberance of a tropical Southeast Asian forest:

“The natural beauty of the scene was so great, however, that these occasional obstructions, so far from diminishing, actually heightened the charm of the whole. The forest was full of the most luxuriant underwood, creepers, palms, and fern plants; the latter, in many instances sixteen feet high, proved a no less effectual screen against the burning rays of the sun than did the palms and other trees.”5

No tigers or wild boars were spotted but they did encounter a large green snake in a tree. In her diary, Pfeiffer melodramatically described the shooting of this snake as a dangerous battle against a fork-tongued devil.

After the snake was killed, one of their Malay assistants dragged it out of the tree with an impromptu noose made from grass and after skinning the reptile, gave it to some Chinese plantation workers nearby.

Later that afternoon, returning to the same spot where they had killed the snake, Pfeiffer could not resist checking to see if the plantation workers were eating the reptile. She rushed up to one of their houses to find out, but sensed that the men wished to hide their repast: “I entered very quickly and gave them some money to be allowed to taste it. I found the flesh particularly tender and delicate, even more tender than that of a chicken.”6

The same day, Pfeiffer also “paid a visit to a sugar-refining establishment situated upon the banks of the [Kallang] river”. She described the operation:

“The cane is first passed under metal cylinders, which press out all the juice; this runs into large cauldrons, in which it is boiled, and then allowed to cool. It is afterwards placed in earthen jars, where it becomes completely dry.”7

Customs of the Chinese in Singapore

On another day, Pfeiffer observed the funeral procession of a wealthy Chinese merchant. She joined the long line of mourners who seemed, to her, strangely to be in high spirits, and observed everything about the funeral carefully. She would write a detailed account of the rituals, all of which were very new and mysterious to her. She noted:

“The friends and attendants, who followed the coffin in small groups without order or regularity, had all got a white strip of cambric bound round their head, their waist, or their arm. As soon as it was remarked that I had joined the procession, a man who had a quantity of these strips came up and offered me one, which I took and bound round my arm.”8

She also noted how Chinese burial customs required public displays of deep grief which did not appear to be completely genuine. On reaching the grave, the relatives “at first threw themselves on the ground, and, covering their faces, howled horribly, but, finding the burial lasted rather long, sat down in a circle all round, and, taking their little baskets of betel, burnt mussel-shells, and areca-nuts, began chewing away with the greatest composure”.

Pfeiffer’s stay also coincided with the Mid-Autumn Festival, which she called the lantern festival. She recalled:

“From all the houses, at the corners of the roofs, from high posts, &c., were hung innumerable lanterns, made of paper or gauze, and most artistically ornamented with gods, warriors, and animals. In the courts and gardens of the different houses, or, where there were no courts or gardens, in the streets, all kinds of refreshment and fruit were laid out with lights and flowers, in the form of half pyramids on large tables.”9

India and Onwards

After a month in Singapore, Pfeiffer was ready to press on. Her next destination was India and, grumbling to herself, she bought another second-class ticket for the P&O steamer Braganza, under Captain Potts, which sailed on 8 October 1847. The Singapore Free Press was not fooled this time; it did not list her name in the list of first-class passengers.

Pfeiffer travelled to Calcutta and then made her way, again alone, across northern India, where among other things, she rode an elephant during a tiger hunt.

After India, she headed to the Persian Gulf and reached Baghdad. Then, again against all good sense and advice, Pfeiffer joined a Kurdish camel caravan and crossed the vast dessert to Mosul and then to Russia. Along the way, she was kidnapped by a Cossack and kept imprisoned overnight until her travel papers could be checked. She finally reached Vienna, via Greece and Italy, in October 1848.

Second Visit to Singapore (1851)

Three years later, in March 1851, Pfeiffer set off again for another circumnavigation. She first sailed to London and from there to Cape Town, where she hoped to travel into the interior of Africa. However, once there, she found that it was impossibly expensive. Fortunately, a German brig was then lying in harbour bound for Singapore and there, she well knew, “[one] may find ships to all the regions of the earth”. Here, her special status as a celebrity lady traveller and writer got her a discount; she would only be charged for her board.

On 16 November 1851, the Louisa Frederika dropped anchor in the bustling harbour of Singapore. Again, as with her first visit in 1847, Pfeiffer was warmly welcomed by the Behn family.

Pfeiffer’s reputation now preceded her, and The Singapore Free Press announced the arrival of the “undaunted and adventurous traveller” whose “remarkable courage and perseverance” were now near legendary.10

Shortly before Pfeiffer’s arrival, a small cottage had been built in the forest far from the town. It was to be used as a holiday retreat by several families. As it happened to be unoccupied, Theodor Behn knew that he could give Pfeiffer no greater pleasure than “passing a few days in the midst of the jungle, and enjoying to [her] heart’s content the scenery, and the amusement of searching for insects”.11

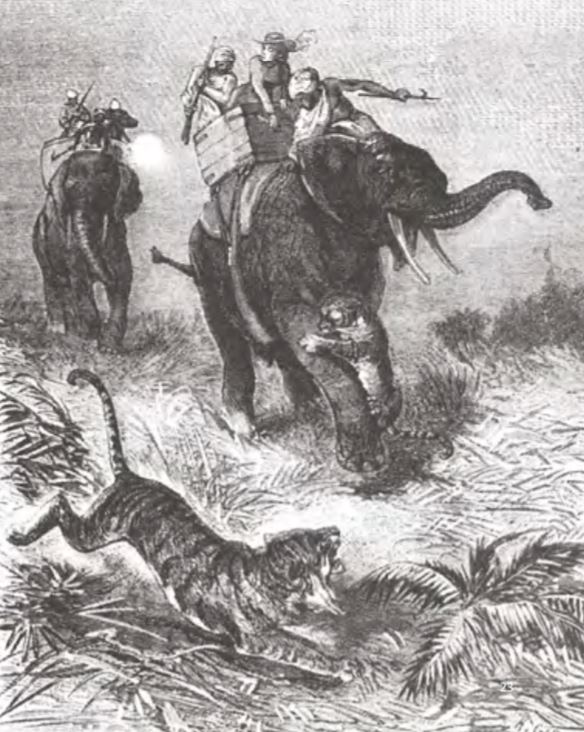

Herr Behn sent her a boat to visit nearby islets, and five Malays to help her. The men came every morning and asked if she wanted the boat. If she didn’t, they would join in her rambles through the jungle hunting insects and protecting her from tigers.

“These animals have of late increased tremendously”, she was told. And the beasts “do not hesitate to break into the plantations and carry off the labourers in broad daylight. In the year 1851, it is stated that no less than the almost incredible number of four hundred persons were destroyed by them”.12 But even these harrowing stories could not deter her from “finding the greatest delight in roaming from morning till evening in these most beautiful woods”.13

Pfeiffer’s Malay companions were armed with muskets and long knives. “We saw traces of tigers every day; we found the marks of their claws imprinted in the sand or soft earth; and one day at noon, one of these unwelcome guests came quite near to our cottage, and fetched himself a dog, which he devoured quite at his leisure only a few hundred steps off.”14

Although Pfeiffer wrote in her book that 400 people a year were killed by tigers in Singapore, she was in fact repeating a widespread myth that virtually every visitor in those years was told. The British naturalist Alfred Russel Wallace would repeat the same dramatic story in his book, The Malay Archipelago, published in 1869. In fact, the death toll from tiger attacks was more like 20 per year.15

Collecting Specimens

While tigers were a concern, the richness and diversity of the forest made it far too enticing for Pfeiffer to cower indoors. She wrote:

“I was busy with the beautiful objects that presented themselves to my observation at every step. Here merry little monkeys were springing from bough to bough, there brightly plumed birds flew suddenly out; plants that seemed to have their roots in the trunks of the trees, twined their flowers and blossoms among the branches or peeped out from the thick foliage; and then again the trees themselves excited my admiration by their size, their height, and their wonderful forms. Never shall I forget the happy days I passed in that Singapore jungle.”16

On 30 November 1851, Pfeiffer wrote to Vinzenz Kollar, her museum contact in Vienna. The insect collecting was not as productive as she had hoped. Nevertheless, she was sending back another cache of specimens.

“Oh my dear Herr Kollar,” Pfeiffer wrote, “you cannot believe how difficult it is to send collections when funds are so extremely limited as with me.” She then asked Kollar to sell the specimens not needed for the museum’s collection and to turn them “into money because to [her] every small profit is of great value.”17

Unfortunately, Pfeiffer had not brought enough alcohol to preserve the many specimens that could not be dried and preserved. All of her larger specimens rotted almost immediately in the hot and humid tropical weather. She did manage to collect a new species of mole cricket (Gryllotalpa fulvipes) and for almost a century, hers was the only specimen ever found.18

She was, however, more successful in drying seaweed and preserving fish, the latter earning her a handsome £25 from the British Museum, according to the naturalist Alfred Wallace. He later wrote to Samuel Stevens, their shared London agent, from Singapore saying that he, too, procured fish in the market but wondered, “How did Madame Pfeiffer preserve hers?”19

Pulau Ubin

During her time in Singapore, Pfeiffer also visited Pulau Ubin, which she described as being off Shangae (Changi). She found it so interesting that she advised her readers not to neglect visiting this island:

“… it has a natural curiosity to show which no geologist I think has been able satisfactorily to explain. The masses of rock on the sea-shore – namely, instead of being smoothed and rounded as they usually are when constantly washed over by the tides – are angular, sharp-edged, and split into various compartments. The clefts are from a foot to a foot and a half deep, and the edges stand one or two feet apart.”20

Pfeiffer also noted that “a magnificent lighthouse had been built” from the granite quarries of Ubin.21 This was the Horsburgh Lighthouse on Pedra Branca.

Living with Head-hunters

On 2 December 1851, Pfeiffer departed for Sarawak. Her hosts, the representatives of the absent James Brooke, the “White Rajah” of Sarawak,22 secretly thought this middle-aged lady traveller was rather ridiculous. When Wallace later visited Sarawak in 1854, he was told that she resembled the fictitious Mrs Harris in the satirical magazine Punch. This was not a very flattering image as Mrs Harris was an ageing, opinionated, gossipy, bossy and clearly ridiculous busybody.

While in Sarawak, Pfeiffer travelled through the territory of the Dayak head-hunters, an unprecedented journey for a European. She stayed in a succession of Dayak longhouses, sometimes with freshly decapitated human heads drying over a fire near where she slept. Of one encounter with these heads, she wrote:

“They were blackened by smoke, the flesh only half dried, the skin unconsumed, lips and ears shrivelled together, the former standing wide apart, so as to display the teeth in all their hideousness. The heads were still covered with hair; and one had even the eyes open, though drawn far back into their sockets.”23

Pfeiffer’s response to this was interesting though. She wrote:

“I shuddered, but could not help asking myself whether, after all, we Europeans are not really just as bad or worse than these despised savages? Is not every page of our history filled with horrid deeds of treachery and murder?”24

Pfeiffer subsequently made her way through the very heart of Borneo to the Dutch port of Pontianak in the south. When she arrived, the Dutch officials were utterly dumfounded that she had crossed the mountains from Sarawak. The Athenaeum magazine called it “one of the most extraordinary journeys made by a European in Borneo”.25

Close Encounters with Cannibals

Pfeiffer later made her way through Sumatra where she almost came to an untimely end. Again she insisted on visiting the remotest and wildest places, to boldly go where no European had gone before. Her goal was to reach an inland lake, Lake Toba, reportedly deep in the territory of the infamous cannibals – the Batak people. No European had ever seen Lake Toba.

She pushed on into Batak territory, venturing further than any European had ever reached, each day negotiating permission to enter the territory of the next village.

Eventually, Pfeiffer’s presence could no longer be tolerated. One day, she was encircled by 80 armed men, shouting and gesticulating violently. Despite the fact that she could not understand a word of their language, there was no mistaking that they meant business. “They pointed with their knives to my throat, and gnashed their teeth at my arm, moving their jaws then, as if they already had them full of my flesh.”26

Pfeiffer, however, had memorised a little speech for just such an occasion. Standing up and looking straight in the eye of the chief closest to her, she clapped him familiarly on the shoulder, and said in a half-Malay and half-Batak phrase, “Don’t eat me. I am an old woman so my flesh is very tough.”27

The tension was dispelled, and laughing, the armed men dispersed. Unfortunately, Pfeiffer never made it to Lake Toba as she was eventually forced to turn back.

Her journey continued to the Spice Islands of Maluku where she trekked all the way across the mountainous island of Seram to visit the Alfur people, who were also said to be head-hunters. From Batavia, her fame gained her the offer of a free passage across the Pacific to California.

From California, Pfeiffer visited Peru and Ecuador. Unable to swim, she almost drowned when she fell off a boat in Ecuador. Travelling across Panama, she landed at New Orleans where she was outraged by the slave trade. Eventually she toured New York and Boston before returning home via London in 1855. She had circled the globe alone for a second time.

Final Journey: Madagascar (1856–58)

Pfeiffer’s next and last journey in 1856 was to a land almost completely unknown to Europeans: the Indian Ocean island of Madagascar. To reach it, she had to travel via South Africa and Mauritius.

When Pfeiffer arrived in Madagascar, she became inadvertently involved in an attempted coup against the queen by a French businessman, and she and the conspirators were banished from the island.

Tragically, on her way to the coast under armed guard, Pfeiffer contracted the infamous “Madagascar fever”. The queen had ordered them to be taken on a long and circuitous route through swampy terrain, rather than the direct eight-day walk back to the port. Fortunately, Pfeiffer eventually made it safely to Mauritius to convalesce.

Disappointed that she had collected so few specimens on this trip, Pfeiffer still hoped to travel further, but it was not to be; the fever kept returning. There was only one journey left in her – to return home.

Emaciated and weak, she finally reached Vienna in mid-September 1858. A few weeks later, she succumbed to her illness in the night of 28 October. She was only 61.

By the time she died, Pfeiffer had become one of the most famous women in the world. She had seen more of the world than any other woman before her. But wanderlust at last had killed her.

John van Wyhe at Lake Toba, following in Ida Pfeiffer’s footsteps.

John van Wyhe at Lake Toba, following in Ida Pfeiffer’s footsteps.

John van Wyhe talks about the research process behind his book on Ida Pfeiffer and his assessment of her as a traveller and collector.

You’re known as an expert on Charles Darwin and Alfred Russel Wallace. How did you learn about Ida Pfeiffer and why did she intrigue you?

I came across her while doing research for my 2013 book on Alfred Russel Wallace. I wanted to read about as many travellers to Singapore and Southeast Asia in those years as possible in order to enrich the story I could tell. Pfeiffer was one such traveller. Her writing was excellent and her adventures unbelievable. I could not resist reading more and more about her.

What was the research process like?

I spent four to five years researching this book. I bought all of her books and made extensive use of resources such as Google Books and online historical newspaper collections. From these and other sources, I discovered many descriptions of her that had not been found before. Plus, I read all of the German-language articles and books that have been written about her.

Did you manage to use any resources from the National Library?

I consulted the Singapore newspapers archives in the NewspaperSG portal. This is an amazing treasure trove of materials on the history of 19th-century Singapore.

Ida Pfeiffer is a remarkable person. How did she manage to see so much of the world, and to do so as a woman travelling alone?

Pfeiffer never gave up, no matter how much hardship she had to endure. In addition, she was a woman doing what no woman had ever done before, so she received a lot of help and sympathy that a man would not have received in similar circumstances. She often received free tickets on ships travelling great distances and hotel keepers would not charge her for a stay because they were so honoured to meet this famous traveller.

As a traveller and a collector, how would you compare her to Wallace?

Pfeiffer made many journeys that were far more adventurous (or reckless) than Wallace’s. But as a self-taught collector, she was nowhere near his level of scientific knowledge. Wallace, however, only collected a very narrow spectrum of the natural world, almost nothing but insects, birds and mammals. Pfeiffer collected these as well as plants, minerals, fungi, seaweed, crustaceans, fish, and ethnographic artefacts of many kinds.

You’ve obviously spent a lot of time thinking about Pfeiffer. What do you find most striking about her and what do you think were her weak points?

She was a fascinating human being and her exploits were amazing. She was a woman of her time though, and as a historian, one cannot just praise things that agree with our modern values and condemn things that don’t.

I feel that what she lacked most was preparatory research. She did almost no research about the places she was going to visit. She could have understood much more about the places she visited if she had. For example, when she travelled in China, she was amazed to see people eating with chopsticks, which she had never heard of. This was astonishingly ignorant. Any basic book on China would have told her about such things.

She was also very stubborn. She never followed the advice of local experts, no matter how dangerous they said a part of her journey would be. She would just go ahead anyway. This includes her final destination, Madagascar, which ultimately cost her her life.

Finally, you’ve written extensively about Darwin and Wallace, and now Pfeiffer. Who’s next on your list?

I have returned to my primary area of research on Darwin and Wallace and I’m about to submit another book on Darwin, which has been 10 years in the making.

John van Wyhe’s Wanderlust: The Amazing Ida Pfeiffer, the First Female Tourist (2019) retails at major bookshops and is also available for reference at the Lee Kong Chian Reference Library and for loan at selected public libraries (Call nos.: RSING 910.41 VAN and SING 910.41 VAN). The 1888 French edition of Ida Pfeiffer’s second book, Voyage autour du monde de Mme. Ida Pfeiffer (Voyage Around the World by Mme. Ida Pfeiffer), translated by E. Delauney was on display at the “On Paper: Singapore Before 1867” exhibition held at level 10 of the National Library Building.

Dr John van Wyhe is a historian of science who has written extensively about Charles Darwin and Alfred Russel Wallace. He is the author of Wanderlust: The Amazing Ida Pfeiffer, the First Female Tourist (2019).

Notes

-

Pfeiffer, I. (1852). A woman’s journey round the world: From Vienna to Brazil, Chili, Tahiti, China, Hindostan, Persia, and Asia Minor (p. 118) [unabridged translation]. London: Illustrated London Library. Retrieved from Internet Archive website. ↩

-

Page 3 miscellaneous column 1. (1847, September 9). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, p. 3. Retrieved from NewspaperSG ↩

-

Pfeiffer, 1852, p. 118. ↩

-

Pfeiffer, 1852, p. 120. ↩

-

Pfeiffer, 1852, p. 122. ↩

-

Pfeiffer, 1852, p. 124. ↩

-

Pfeiffer, 1852, p. 123. ↩

-

Pfeiffer, 1852, p. 125. ↩

-

Pfeiffer, 1852, p. 127. ↩

-

The Free Press. (1851, November 21). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Pfeiffer, I. (1855). A lady’s second journey round the world: From London to the Cape of Good Hope, Borneo, Java, Sumatra, Celebes, Ceram, the Moluccas, etc. California, Panama, Peru, Ecuador, and the United States (vol. I, p. 50). London: Longman, Brown, Green, and Longmans. (Not available in NLB holdings) ↩

-

Pfeiffer, 1855, vol. I, p. 51. ↩

-

Pfeiffer, 1855, vol. I, p. 51. ↩

-

Pfeiffer, 1855, vol. I, p. 52. ↩

-

Wallace, A.R. (1869). The Malay archipelago: The land of the orang-utan, and the bird of paradise: A narrative of travel, with studies of man and nature (vol. II, p. 37). London: Macmillan & Co. Retrieved from Internet Archive website. Also see van Wyhe, J. (Ed.). (2014). The annotated Malay Archipelago by Alfred Russel Wallace (p. 86). Singapore: NUS Press. (Call no.: RSING 959.8 ANN); van Wyhe, J. (2013). Dispelling the darkness: Voyage in the Malay Archipelago and the discovery of evolution by Wallace and Darwin (pp. 83–86). Singapore: World Scientific Publishing. (Call no.: R 576.82092 VAN) ↩

-

Pfeiffer, 1855, vol. I, p. 51. ↩

-

Quoted in Riedl-Dorn, C. (2001). Ida Pfeiffer (pp. 265–269). In W. Seipel (Ed.), Die Entdeckung der Welt. Die Welt der Entdeckungen Österreichische Forscher, Sammler, Abenteurer. Vienna: Skira. (Not available in NLB holdings) ↩

-

NParks Flora & Fauna web. (2019). Gryllotalpa fulvipes (Saussure, 1877). Retrieved from Flora & Fauna Web. ↩

-

Wallace to Samuel Stevens, 12 May 1856. See van Wyhe, J., & Rookmaaker, K. (Eds.). (2013). Alfred Russel Wallace: Letters from the Malay Archipelago (p. 80). Oxford: Oxford University Press. (Call no.: RSEA 508.092 WAL) ↩

-

Pfeiffer, I. (1856). A lady’s second journey round the world: From London to the Cape of Good Hope, Borneo, Java, Sumatra, Celebes, Ceram, the Moluccas, etc. California, Panama, Peru, Ecuador, and the United States (p. 53). New York: Harper & Brothers. Retrieved from Internet Archive website. ↩

-

Pfeiffer 1855, vol. I, p. 49. ↩

-

The White Rajahs were a dynastic monarchy of the British Brooke family, who ruled Sarawak from 1841 to 1946. The first White Rajah was James Brooke, who ruled until his death in 1868. As a reward for helping the Sultan of Brunei suppress “insurgency” among the indigenous peoples, Brooke was made Rajah of Sarawak in 1841. ↩

-

Pfeiffer, 1855, vol. 1, p. 84. ↩

-

Pfeiffer, 1856, p. 60. ↩

-

Anon. (1861, August 3). [Review of] Ida Pfeiffer’s last travels. The London Review, vol. 3, p. 153. ↩

-

Anon, 1861, p. 153 ↩

-

Pfeiffer’s words are quoted by von Humboldt. See Müller, C. (Ed.). (2010). Alexander von Humboldt und das Preußische Königshaus. Briefe aus den Jahren 1835–1857 (p. 255). Severus Verlag. (Not available in NLB holdings) ↩