The Theatres of Bangsawan

In the days before cinema, bangsawan performances entertained the masses. Tan Chui Hua looks at the rise and fall of bangsawan venues in Singapore.

“With a bottle of champagne broken on the door-step, the new Theatre Royal, in North Bridge Road, was opened officially on Saturday night, the Wayang Kassim’s Trip to Fairyland being staged before a packed house, the conclusion of the formal opening ceremony.”1

In the early decades of the 20th century, before the days of cinema, residents of Singapore eagerly flocked to bangsawan2 performances to be entertained. Performed in Malay, bangsawan featured acting and singing as well as music provided by a live orchestra. Back then, it was one of the few forms of mass entertainment available.

Such was the draw of bangsawan in the pre-war years that people living in Tanjong Pagar would travel by bullock cart all the way to North Bridge Road to catch a performance at the purpose-built Theatre Royal. Mohamed Sidek bin Siraj, a former civil servant and bangsawan patron, recalls in his oral history account:

“The third class is about $1 and the first class in front is about $3 or something… There’s no other entertainment for the Malays except bangsawan. Even that, it started after eight and then finished up at twelve. If you don’t have the transport you have to walk. People will use a bullock-cart from Tanjong Pagar to see bangsawan and say about 10 or 12 people will go back in a bullock cart to Tanjong Pagar.”3

Theatre Royal was just one of a handful of venues in Singapore that staged bangsawan performances. While much research has been carried out on the art of bangsawan, less has been written about the places that played host to such shows. Although secondary source materials on these venues are scant, by piecing together occasional mentions in newspaper reports, advertisements, archival records and oral history interviews, a story of the former theatres of bangsawan emerges.

Of Wooden Structures, Zinc Roofs and Tents

It is unclear when commercial performances aimed at the Asian population in Singapore began, but by the late 1800s, advertisements and reports of such events began appearing in the newspapers of the day.

By all accounts, native theatre, or bangsawan, and other Asian entertainment such as circuses and Parsi theatrical acts from Gujarat, India, took place in tents or semi-permanent constructions of canvas, wood and bamboo.4

A rare review in the Daily Advertiser newspaper in 1891 provides us with a glimpse of what such performing venues must have been like then:

“A Penang Native Operatic Company, called the Empress Victoria Jawi Pranakan Theatrical Company, which is conducted on the same lines as the Parsee Company which visited this city some eight or ten years ago, opened last night in Jalan Besar, opposite the Kampong Kapor Bridge. The building is a wooden one with zinc roofing, and is both airy and commodious, but the internal arrangement is susceptible of improvement. The sceneries for a native company, are passable… Last night the building was crammed with natives. There were however a few Europeans and Eurasians, but they left before the play was concluded.”5

Besides this venue at Jalan Besar, usually referred to as the Parsi Theatre, there were mentions of other performance sites in other newspapers. For instance, in 1887, a member of the public who had caught a performance by The Prince of Wales Theatrical Company wrote in The Straits Times Weekly Issue that the troupe performed nightly at Cheng Tee’s theatre on North Bridge Road in Kampong Glam, and praised the performers for singing the songs of “Hindoostan and England in high Malay”.6

Along the same road, Lee Peck Hoon Theatre was mentioned in the early 1900s for its bangsawan acts. Described as “fairly cool and comfortable” and “lighted by acetylene gas”, the theatre was named after its Peranakan proprietor, who was the sub-manager of the Straits Steamship Company. In 1902, the staging of a play Indra Sabha by a Malay theatrical company was very well received, and the 3rd Madras Infantry – including several of its officers – was reported to have turned up in force.7

Advertisements in the early 1900s also mentioned a “North Bridge Road Theatre”,8 usually leased by the popular Wayang Kassim troupe, also known as Indra Zanibar Royal Theatrical Company. At 485 North Bridge Road was the “New Parsi Theatre Hall” that was frequently leased by Wayang Pusi from Penang. The latter – also known by various names such as Indra Bangsawan, The Queen Alexandra Theatrical Company and the Empress Victoria Jawi Peranakan Theatrical Company – is commonly acknowledged to be the first bangsawan troupe in Malaya. A few doors away at 499 North Bridge Road was Alexandra Theatre Hall, or Alexandra Hall, leased by Opera Yap Chow Tong, a bangsawan troupe.

What did these early theatres look like? Except for Theatre Royal, no photographic records of these theatres have been found so far, so we only have the description of the Jalan Besar theatre as a wooden building with a zinc roof.

In 1896, The Mid-Day Herald newspaper highlighted the lack of a brick structure for “native theatre” and the hazardous conditions of the Jalan Besar theatre, despite the fact that it was certified by the Municipal Engineer as fit for use as a theatre just a year ago:9

“The building in which the Parsee Theatre [Jalan Besar theatre] is performing does not seem to present a stable appearance. Were it not for the ponderous props, the building will, in all probability, collapse. As large numbers of people congregate here nightly, we think the Municipality should thoroughly satisfy itself that the building is perfectly safe, as in the event of a collapse, hundreds, if not thousands, are likely to be killed or injured. It would pay anyone to erect a commodious brick structure to take the place of the present one, as native companies are almost constantly here.”10

By the early 20th century, more solid structures had been built. A 1903 Straits Times article complaining of overcrowding at the North Bridge Road Theatre during Wayang Kassim’s performances mentioned brick walls along the main entrance:

“Not only was every available seat occupied, but the very passages in the centre of the hall and in the wings underneath the zenana class were all densely packed, being taken up by people who could not, either for love or money, find sitting accommodation of any kind within the four walls of the building. Those among the audience who left before the conclusion of the play experienced very great difficulty in making their exit, having to carefully and slowly thread their way among the maze of human beings who thronged the passages and occupied every coign of vantage, from the main entrance up to the very stage itself… There is seemingly only one public entrance from the main thoroughfare, bordered on either side by a brick wall to the length of about 30 feet or so; and in the case of a panic succeeded by a block here, the result would be too awful to contemplate.”11

Such was the state of the theatres catering to local entertainment that when Theatre Royal opened in 1908, it was to much fanfare and praise.

Theatre Royal

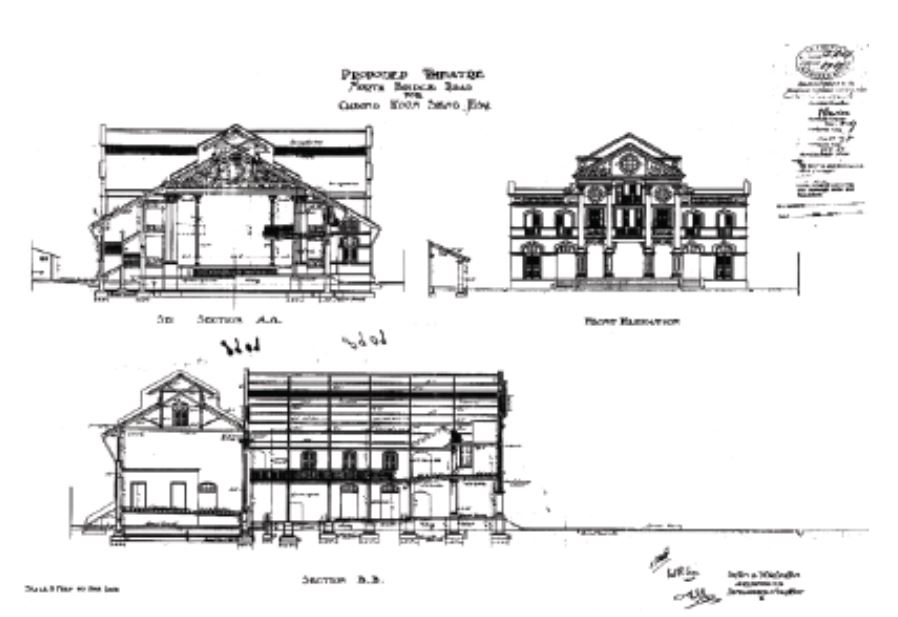

Located at the site now occupied by Raffles Hospital, Theatre Royal is believed to be the first “permanent” theatre for the so-called “native” form of entertainment.12 It was described as a “most substantial edifice of brick, iron and stone, with seating accommodation for about 1,300 people”.13

Theatre Royal was the brainchild of Chinese Peranakan businessman Cheong Koon Seng, who was also a Municipal Commissioner and a Justice of the Peace.14 Designed by Messrs Swan and Maclaren, the theatre was reported to be built along European lines in which strength and safety of the building were taken into regard.15 In 1908, The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser gave a detailed description of the theatre prior to its opening:

“The front of the building is of very ornamental design and the main entrance is by three arches opening into a spacious hall off which is the pit and stalls both of which have ample emergency exits on either side. The auditorium is rectangular on plan about 70 feet long by 60 feet deep and is provided with good dressing room accommodation and the proscenium arch is 38 feet wide by 24 feet high. In front of the stage is the usual orchestra well. The upper part of the auditorium has a horseshoe-shaped circle and gallery and is reached by two wide and easy staircases from the side of the main entrance. The building is substantially constructed, steel being largely used, the circle being supported upon steel columns with cantilevers of the same material projecting beyond the girders to form the shape. The roof is lofty and well-ventilated and supported on steel columns. The building is pleasing in appearance, well-lighted and ventilated and the comfort of the audience and the performers has been studied.”16

Even members of royalty would make an appearance there as bangsawan fan, Abu Talib bin Ally, recalled:

“Itu theatre dia, banyak orang-orang kenamaan tengok. Kalau raja-raja yang hendak tengok semua, nanti dia taruh kain kuning tempat dia.”17

(Translation: At his theatre, many dignitaries went to watch [bangsawan]. If royals attended the shows, yellow cloth would be placed over their seats.)

The opening of Theatre Royal heralded the golden age of bangsawan in Singapore and Malaya. More and more bangsawan troupes were formed, and as appetite for the performances grew, the newspapers were filled with advertisements for local and touring bangsawan companies from the 1910s till the 1930s. For instance, in 1909, Cheong Koon Seng launched his own bangsawan company, Star Opera Company, which was based at Theatre Royal.18 Splinter groups also formed as members of established troupes left to establish their own acts.19

The increased demand for bangsawan also led to more venues for the performances. New theatres were mentioned in the papers, such as Beyrouth Theatre, which opened in 1921 opposite Geylang Police Station on Geylang Road. Beyrouth was home to Nahar Opera, a large bangsawan troupe comprising some 90 performers and 28 musicians.20

Amusement parks such as Great World in River Valley and Happy Valley in Tanjong Pagar also hosted regular bangsawan programmes. Zubir Said, composer of Majulah Singapura, the national anthem of Singapore, started out as a musician in the City Opera bangsawan troupe based in Happy Valley after arriving in Singapore in 1928. He recalled that the hall, as big as Victoria Theatre, was specially built for the performances, and that there were also living quarters on the park grounds for bangsawan performers.21

Besides local bangsawan troupes, travelling acts from the region also performed at the theatres and halls in Singapore. Sometimes, performing tents would be specially erected for the duration they were based on the island. In 1928, The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser reported on the popularity of such shows:

“An attraction which never fails to draw crowds in any town either of Malaya or of the Dutch East Indies is described by a visit of a Bangsawan, or opera company… The personnel… is generally mixed, containing Malays, Eurasians, and sometimes Chinese players. Travelling from town to town, like a circus, the company pitches its tent on the medan and at once begins to advertise its presence by the distribution of leaflets.”22

Hamid bin Ahmad, who wrote bangsawan scripts, said in his oral history interview in 1987 that tents for bangsawan performances used to be erected on the vacant plot of land on Geylang Road, just beside the MRT station facing City Plaza.23

Bangsawan, however, was not the only draw of these performing venues. In an era of heady live entertainment before cinema became mainstream, performances such as variety shows, revues, vaudevilles, circuses, magic acts, acrobatics and even sports events were frequently staged. Theatre Royal and Alexandra Hall, for example, were famous for hosting high-profile wrestling and boxing matches featuring local and overseas champions in the pre-war years. The former was said to be filled to the brim with spectators every week for boxing promotions.24

A Gradual Decline

“I am afraid the talkies and the slump together are trying to oust the Bangsawan from its rightful place in the Malayan scheme of things.”25

As more cinemas were built and watching films became a popular pastime among Singaporeans, live entertainment such as bangsawan became less attractive. By the late 1930s, advertisements touting bangsawan performances became few and far between.

Mohd Buang bin Marzuki, a former violinist and pianist for various bangsawan troupes, pointed to the advent of films in the 1930s as the start of bangsawan’s decline:

“…ini gambar boleh bercakap… Singapore punya orang semua ini gambar boleh bercakap, “Baguslah, bercakap” dia orang bilang. Jadi semua orang bertumpulah di situ. Wayang [bangsawan] dah jadi kendur merosot. Baik-baik boleh dapat $30, makin kurang, kadang $20, kadang satu sen [pun] tak dapat … Gambar bagus-bagus main, semua bercakap menyanyi. Itulah yang jadi bangsawan merosot, sudah kurang orang. Sekali masuk ini filem, Melayu punya, terus sekali habis. Filem P Ramlee sekali masuk, habis sekali … gambar Melayu.”26

(Translation: The pictures could talk… The people in Singapore all praised these talking pictures, so all of them went to the pictures. Bangsawan thus began declining. On a good day, we could make $30, sometimes less, $20, sometimes not even a cent… The nice pictures could talk, sing. So bangsawan declined, fewer people. When Malay films entered the scene, it became even worse [forbangsawan]. When P. Ramlee’s films were launched, it became even worse.)

When Cheong Koon Seng died in 1934 at the age of 55, his family sold Theatre Royal to Amalgamated Theatres, the company managing Capitol and Pavilion cinemas.27

Amalgamated Theatres immediately set to work modernising the place. In February 1935, Theatre Royal, “once the favourite Star Opera”, had its grand opening with a Hindustani film, Krishna Sudama, produced by the well-known Ranjit Studio of Bombay.28 The grand dame of bangsawan performances was transformed into a cinema screening films from India, with the occasional live act from Indian theatrical and performing groups.29 Eventually, Tamil talkies replaced bangsawan as the mainstay of the Theatre Royal, now renamed Royal Theatre.

During the Japanese Occupation of Singapore (1942–45), Royal Theatre was known as Indo Gekijo and used mainly to screen approved films and shows for the Indian community in Singapore.30 Bangsawan continued to be performed at Garrick Cinema in Geylang. Bangsawan music was also aired regularly over the radio. Nevertheless, the vibrancy of the bangsawan scene continued its decline.

Bangsawan scriptwriter Hamid bin Ahmad felt that the quality of bangsawan productions deteriorated, especially after the war. He recalled:

“… saya sudah mulai hilang minat menonton kerana bila saya tengok alat-alat bangsawan itu sudah tidak seperti yang biasa saya tonton di dalam tahun-tahun 30-an dulu… sebelum perang Jepun. Begitu cantik begitu gemilang segala-gala yang dialatkan. Jadi apa lagi bangsawan waktu lepas Jepun ni dia orang buatkan bangsawan khemah. Di buat panggung sendiri seperti panggung wayang Cina, memang, kalau tak silap, kontraknya kontrak-kontrak itu orang kontrak panggung wayang Cina tulah. Buat panggung, habis, lantainya jugak berbunyi bila kita pijak tu semua, banyak sudah mulai. Saya pikir di waktu itulah mulai bangsawan mulai turun. Mulai standard bangsawan telah turun dari lepas perang Jepun lah tidak dapat naik kembali.”31

(Translation: I lost interest in watching bangsawan because I saw that the standard was no longer the same as that in the 1930s… before the war with Japan. The performances then were so beautiful, so alluring. After the Occupation, the performing tents for bangsawan were like the stages for Chinese wayang. If I’m not mistaken, they had agreements with the Chinese who built the stages. The floor made sounds when you stepped on it. I feel that was when bangsawan really declined. The standard of performance dropped after the war and did not recover after that.)

The gradual conversion of bangsawan venues to movie theatres sounded the death knell for bangsawan. In 1947, Alexandra Hall underwent extensive renovations to become Diamond Theatre, another cinema for the screening of Tamil talkies.32 Interestingly, bangsawan as an art form began evolving too. From being popular commercial theatre, it began taking on the form of “traditional” Malay theatre and was staged in smaller arts venues on occasion. Advertisements for bangsawan performances became very infrequent.

Diamond Theatre and Royal Theatre continued with their new leases of life as Tamil cinemas until the late 1970s. In 1970, the government announced its land acquisition plans in the Rochor area, which included the sites of both theatres. By the end of the 1970s, the chapter on theatres specially built for bangsawan performances finally came to a close when these venues were demolished, making way for urban redevelopment.33

THE ALLURE OF BANGSAWAN

It is believed that the first bangsawan troupes made their appearance in Singapore in the late 19th century, inspired by the travelling Parsi theatre groups from Gujarat, India, which started touring Malaya and the Dutch East Indies in the 1870s.34

The first recorded bangsawan troupe, or at least the first known to use the term bangsawan, which means “nobility” in Malay, is Wayang Pusi or Indra Bangsawan troupe from Penang. The troupe was also known as The Queen Alexandra Theatrical Company and the Empress Victoria Jawi Peranakan Theatrical Company.35

By the turn of the 20th century, a number of bangsawan companies had been established in Malaya, such as Opera Yap Chow Thong, Wayang Kassim and the Star Opera Company. A Straits Times article in 1903 described bangsawan as follows:

“The origin of these plays [Malay drama] may be dated from the early part of the 18th century, for records exist in Java of such plays as having been performed there, and these indicate that playhouses similar to the present Malay theatre commonly known as Bangsawan, existed at that time in a crude form. The Bangsawan is an opera of Indian origin conducted in the Malay language. The tunes are mostly borrowed from European operas and songs which at first seems a little odd to the listener, but the Malay – a born improvisator – makes the best of them and seems to adapt these in a truly wonderful manner to his own tongue. The Chinese actors and performers spring from the lowest classes of the population, whereas the Malay actor comes from a highly educated class and is greatly esteemed and liked by his countrymen to whom the Bangsawan is a source of great enjoyment. At first the actors were almost exclusively Jawi Pakans (Kling and Malay descent),36 but in latter years Singapore Malays and Dutch Eurasians of a good class joined the profession and consequently a much higher standard of perfection and culture has been reached.”37

Bangsawan theatre in the pre-war years was primarily a form of commercial mass entertainment, catering to a wide audience in order to compete with other forms of entertainment such as plays, dances, revues and circuses. In 1932, a European who had attended an adaptation of Cinderella by the Starlight Opera Company described the people he saw:

“The audience was composed of a motley crowd – Malays, dressed in all colours of the rainbow, which somehow never seem to clash, predominating. Among the rest of the audience I counted a large number of Chinese, Japanese, Sikhs, Bengalis, Tamils, Eurasians, and one European – myself.”38

Stories in bangsawan theatre were usually adapted from theSejarah Melayu (Malay Annals), the two great Indian epics the Mahabharata and the Ramayana, Arabic tales, Chinese classics, European stories and even Shakespearean plays. Each act was interspersed with performances consisting of orchestral music, songs, dances, comedy skits and novelty acts. It was not uncommon for bangsawan productions to include exotic songs from the Americas, Middle East and India. Musical instruments from different cultures, such as the piano, violin and tabla, were also featured.39

Tan Chui Hua

Researcher and writer Tan Chui Hua has worked on various projects documenting the heritage of Singapore, including a number of heritage trails and publications.

Tan Chui Hua

Researcher and writer Tan Chui Hua has worked on various projects documenting the heritage of Singapore, including a number of heritage trails and publications.

Notes

-

New theatre opened: Wayang Kassim’s first night at the Royal. (1908, June 15). The Straits Times, p. 8. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Bangsawan means “nobility” or “something noble. See Tan, S.-B. (1989, Spring-Summer). From popular to “traditional” theatre: The dynamics of change in bangsawan of Malaysia. Ethnomusicology, 33(2), 229–274, p. 232. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website. ↩

-

Chew, D. (Interviewer). (1991, May 13). Oral history interview with Mohamed Sidek bin Siraj [Transcript of recording no. 001255/6/4, p. 41]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

Van der Putten, J. (2017). The coming of a Malay popular theatrical form (p. 141). In C. Skott (Ed.), Interpreting diversity: Europe and the Malay World. New York: Routledge. (Call no.: RSEA 959.51 INT) ↩

-

Local and general. (1891, November 21). The Daily Advertiser, p. 3. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The Prince of Wales Theatrical Company. (1887, September 21). The Straits Times, p. 12. Retrieved from NewspaperSG; The Daily Advertiser, 21 Nov 1891, p. 3. ↩

-

The Malay Theatre. (1902, August 5). The Straits Times, p. 4; Trouble at a wayang. (1906, December 12). The Straits Times, p. 7; [Untitled]. (1902, August 23). The Straits Times, p. 4. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

No address was given for the “North Bridge Road Theatre” in advertisements ↩

-

Municipal Commission. (1895, August 17). The Mid-day Herald, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Local and general. (1896, June 10). The Mid-day Herald, p. 3. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Crowded theatres. (1903, June 17). The Straits Times, p. 5. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Van der Putten, 2017, p. 145. ↩

-

New theatre opened: Wayang Kassim’s first night at the Royal. (1908, June 15). The Straits Times, p. 8. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Death of Mr. Cheong Koon Seng. (1934, March 20). The Straits Times, p. 12. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

A new native theatre. (1908, April 9). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser (Weekly), p. 233. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser (Weekly), 9 Apr 1908, p. 233. ↩

-

Abdul Ghani bin Hamid (Interviewer). (1991, February 13). Oral history interview with Abu Talib bin Ally [Transcript of recording no. 001216/11/5, p. 95]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website ↩

-

Van der Putten, 2017, p. 153. ↩

-

Mohd Yussoff Ahmad. (Interviewer). (1987, October 8). Oral history interview with Hamid bin Ahmad [Transcript of recording no. 000897/10/1, pp. 9–10]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

Nahar Opera of Singapore. (1921, February 2). The Straits Times, p. 3. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Tan, L. (Interviewer). (1984, August 23). Oral history interview with Zubir Said [Transcript of recording no. 000293/23/6, pp. 81–84]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

The Bangsawan: Incongruities of opera. (1928, October 23). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, p. 3. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Mohd Yussoff Ahmad. (Interviewer). (1987, October 8). Oral history interview with Hamid bin Ahmad [Transcript of recording no. 000897/10/5, p. 56]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

Perreau Family & other Eurasian topnotchers. (1947, November 2). The Sunday Tribune, p. 11. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Penang the original home of Boria. (1932, April 29). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, p. 3. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Mohd Yussoff Ahmad. (Interviewer). (1987, November 14). Oral history interview with Mohd Buang bin Marzuki [Transcript of recording no. 000858/08/7, p. 94]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

Theatre Royal: Acquisition by cinema combine. (1934, October 1). The Straits Times, p. 19. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Theatre Royal: Highly successful Hindustani picture. (1935, February 17). The Sunday Tribune, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Another theatre for Singapore. (1935, February 2). The Malaya Tribune, p. 16; Singapore’s new theatre. (1935, February 4). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Official programme for Tentyo-Setu. (1942, April 28). Syonan Shimbun, p. 4; Indian community holding mass rally tomorrow. (1944, December 9). Syonan Shimbun, p. 2; Mass rallies to condemn sinking of Awa Maru. (1945, May 14). Syonan Shimbun, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Oral history interview with Hamid bin Ahmad, 8 October 1987, pp. 56–57. ↩

-

New cinema for Indian films. (1947, April 30). The Malaya Tribune, p. 6. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Govt to acquire another 32 acres of land. (1970, June 16). The Straits Times, p. 19; The wayang Shakespeare of 1909. (1979, April 23). New Nation, p. 9. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Van der Putten, 2017, p. 141. ↩

-

Van der Putten, 2017, p. 144. ↩

-

These are Jawi Peranakans. ↩

-

The Wayang Kassim. (1903, July 4). The Straits Times, p. 5. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Opera in Malay. (1932, August 23). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Tan, S.-B. (1989, Spring-Summer). From popular to “traditional” theatre: The dynamics of change in bangsawan of Malaysia. Ethnomusicology, 33 (2), 229–274, p. 236. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website. ↩