The Chinese Spirit-Medium: Ancient Rituals and Practices in a Modern World

Margaret Chan examines the fascinating world of tangki worship and explains the symbolism behind its elaborate rituals.

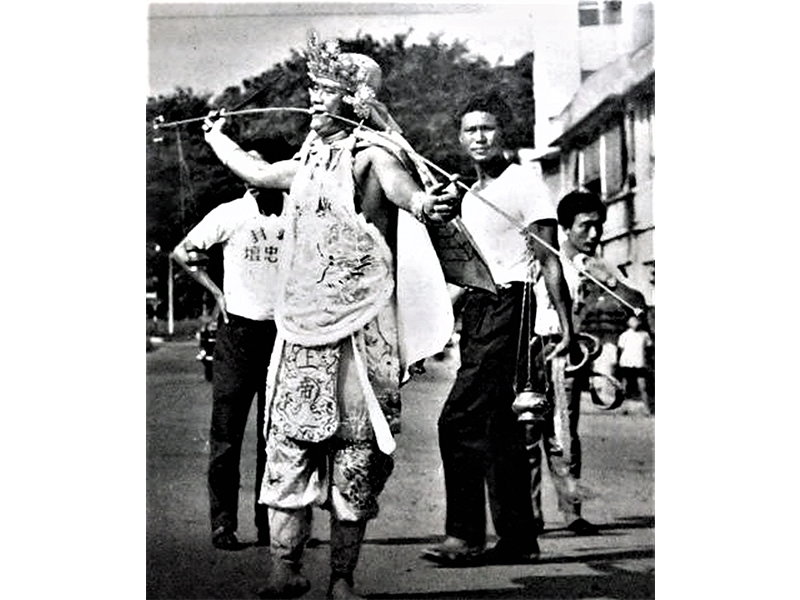

A medium possessed by the hell deity Toa Ah Pek, 1978. Dressed in white, he is one half of the two deities known as Heibai Wuchang (黑白无常). Toa Ah Pek, the White Deity, is said to calculate the length of a person’s life. When it is time for the person to die, he orders his counterpart, the Black Deity, or Ji Ah Pek, to fetch that person’s soul to hell. Ronni Pinsler Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

A medium possessed by the hell deity Toa Ah Pek, 1978. Dressed in white, he is one half of the two deities known as Heibai Wuchang (黑白无常). Toa Ah Pek, the White Deity, is said to calculate the length of a person’s life. When it is time for the person to die, he orders his counterpart, the Black Deity, or Ji Ah Pek, to fetch that person’s soul to hell. Ronni Pinsler Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

In Singapore, the sprit-medium stares straight ahead as five long skewers are driven through the flesh of his back. In Phuket, an umbrella is grotesquely twisted into a gaping wound on the face of his Thai counterpart. Meanwhile in West Kalimantan, steel wires bristle like catfish whiskers around the mouth of an Indonesian medium.

These men, and they are usually men, are Chinese spirit-mediums. They are known by various names: in Singapore, they are called tangki, which is Hokkien for spirit-medium (in Mandarin, they are known as tongji 童乩, which means “child diviner”, or jitong 乩童, which means “divining child”). In Thailand, they are known as masong (马送 in Mandarin), while in Kalimantan they are called tatung (datong 大同 in Mandarin).

Tangki allow their bodies to be possessed by gods, spirits and deities, and they serve as a vessel for these entities. When they are possessed, tangki are regarded as incarnated gods.

Tangki spirit-medium worship has its origins in the people of the Minnan (闽南) region of Fujian province, located along China’s southeastern coast. The Minnan diaspora comprises the Hokkien, Hockchew, Henghua and Hainanese communities, which are well represented in Singapore. As these people are also found in Taiwan, Malaysia, Indonesia, Thailand and Cambodia, tangki worship is also practised in these countries, including Singapore.

Under the Tangki Tent

It used to be a common sight on weekends in housing estates in Singapore: colourful flags planted on grass verges marking a trail to a large tent where Chinese spirit-mediums would be hard at work. Under the tent, one would encounter large crowds, noisy drums and gongs, and bare-chested men going into a trance, hitting themselves with weapons and drawing blood, and moving in a strange fashion. The casual observer might struggle to understand what is going on, but here, as with most religious rituals, things have a certain structure and logic.

Within the tent, the major elements are arranged along cardinal points. The main stage is erected at the northern end of the tent. Here, banners bearing images of the San Qing (三清) – the Daoist triumvirate representing the emanations of pure Tao cosmic energy – are hung. The San Qing altar, which is the main altar to the Three Pure Ones,1 and to the patron god of the tangki, is placed on this stage.

To the left of the San Qing altar (that is, the eastern part of the tent) is the altar of the Five Celestial Armies (五营兵将).2 On the right of the San Qing altar (the western side of the tent) is the altar to the spirits of the Underworld.3

At the southern end of the tent is the altar to Tiangong (天公), the Heavenly Emperor, and his three-tiered papier-mâché palace. From this side of the tent, devotees step out to pray to the open sky, where the face of Heaven is.

Tangki Possession and Performance

According to Chinese folk religion, humans are likened to vessels. Adults are fully filled vessels, while children are half-full vessels that fill up only in adulthood. However, by dint of the date and time they are born (called the Eight Characters, or sheng chen ba zi, 生辰八字, in Mandarin), some adults never become fully filled vessels. Although they are physically adults, they remain as children spiritually. Such people are destined to live a short life but they can prolong their lifespan by agreeing to serve the gods. One way is to be a spirit-medium and become a vessel for gods who descend to the mortal realm to help the people. As spirit-mediums are only “half-filled,” they have “space” for spirits and deities to enter and take control of their bodies.

To denote their status as a spiritual child, many tangki don a dudou (肚兜) over their bare torsos – the diamond-shaped cloth called a stomacher traditionally worn by Chinese babies to prevent colic.

In preparation for the possession ritual, the tangki sits on a chair in the tent as the beating of hand drums and gongs reverberates through the air. The tangki begins to yawn and then retch, signs that possession has begun. A leg balanced on the ball of the foot begins to shake, at first imperceptibly, then faster and faster. His head sways from side to side, picking up speed, and the eyes roll back to show the whites. Suddenly, the tangki leaps up and freezes into a pose typical of the possessing god, such as the Monkey God for instance.

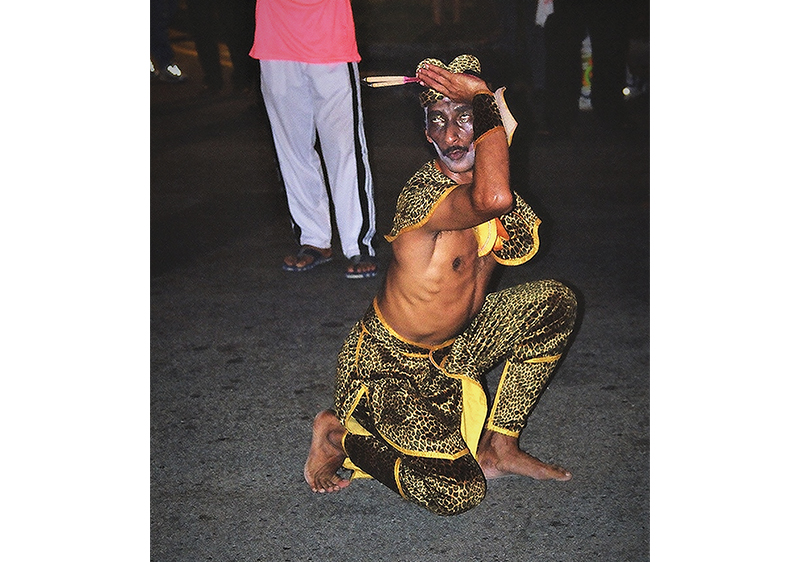

A tangki possessed by the Monkey God in a pose that demonstrates how the god can see far into the distance and can recognise demons even when they are in disguise. Photo taken by Margaret Chan in Singapore, 1999. First used in Chan, M. (2006). Ritual is Theatre, and Theatre is Ritual: Tang-ki, Chinese Spirit-medium Worship. Singapore: SNP Reference. (Call no.: RSING 299.51 CHA)

A tangki possessed by the Monkey God in a pose that demonstrates how the god can see far into the distance and can recognise demons even when they are in disguise. Photo taken by Margaret Chan in Singapore, 1999. First used in Chan, M. (2006). Ritual is Theatre, and Theatre is Ritual: Tang-ki, Chinese Spirit-medium Worship. Singapore: SNP Reference. (Call no.: RSING 299.51 CHA)

The music now changes. The beat quickens to a fast, steady tempo, which signals to observers that in place of the mortal medium now stands a god-incarnate. Assistants rush forward to dress the medium-turned-god in appropriate costumes. Other than the dudou, the tangki now has on riding chaps, represented by what is known as a three-apron “dragon skirt” (longqun 龙裙).

The dragon skirt is typically worn by the character of the military general in Chinese opera. By wearing riding chaps, the tangki is seen as a high-ranking spirit warrior who has travelled on horseback from heaven to earth. This is why the Thai name for spirit-mediums is masong, which means “sent upon a horse”.

Tangki are believed to be spirit warriors who can cure illnesses by vanquishing disease-causing demons and driving them out from the afflicted person. Devotees also believe that tangki bring good fortune when they defeat the spirits of misfortune.4 Popular tangki gods include Guangong (关公), the redfaced hero of the Three Kingdoms era;5 Sun Wukong (孙悟空) the Monkey God;6 and Nezha (哪吒), the child spirit-fighter who fought in the Zhou armies against the Shang empire.7 Even if the medium is possessed by Guanyin (观音) the Bodhisattva of Compassion, it would be in her manifestation as the one who subdues evil spirits.8

Buddhist deities are popular in tangki worship. Shown here is a tangki of Guanyin, the Bodhisattva of Compassion or Goddess of Mercy. Photo taken by Margaret Chan in Singapore, 1999. First used in Chan, M. (2006). Ritual is Theatre, and Theatre is Ritual: Tangki, Chinese Spirit-medium Worship. Singapore: SNP Reference. (Call no.: RSING 299.51 CHA)

Buddhist deities are popular in tangki worship. Shown here is a tangki of Guanyin, the Bodhisattva of Compassion or Goddess of Mercy. Photo taken by Margaret Chan in Singapore, 1999. First used in Chan, M. (2006). Ritual is Theatre, and Theatre is Ritual: Tangki, Chinese Spirit-medium Worship. Singapore: SNP Reference. (Call no.: RSING 299.51 CHA)

Some people denounce tangki practices as devil worship, especially when the medium is possessed by the hell deities of Toa Ah Pek and Ji Ah Pek (together they are known as Da Er Yebo 大二爷伯). Although unnerving to look at, Toa Ah Pek (Elder Uncle), who is dressed in white and has a lolling tongue, and Ji Ah Pek (Second Uncle), who is dressed in black and carries chains and a magistrate’s arrest order, are not demons in the usual sense of the word.

In Chinese folk religion, the two deities, also known as Heibai Wuchang (黑白无常), literally “Black and White Impermanence”, are in charge of escorting the spirits of the dead to the Underworld. Toa Ah Pek, or the White Deity, calculates the length of a person’s life, which is why the tangki possessed by this deity often carries an abacus as a prop. At the end of a person’s life, the White Deity orders his black counterpart to fetch the soul to hell. Ji Ah Pek, or the Black Deity, then goes to the mortal world with his chains and court order to take the soul of that person to the Underworld. Both deities are worshipped in the hope that they might delay the hour of death.9

The two deities are also popular among Taiwanese, Singaporean and Malaysian devotees as gods of wealth. Indeed, emblazoned on the White Deity’s tall hat are the Chinese characters 见生财 (jian sheng cai), which mean “fortune at one glance”. Devotees believe that the Elder and Second Uncle deities can be petitioned for lucky lottery numbers.

The Limping Walk of the Great Yu

After they are possessed, tangki perform a ritual dance known as the magical Yu Step (yubu 禹步). The choreography is known as the “Pacing of the Seven Stars Constellation” (qi xing gang bu 七星罡步) or “Pacing of the Big Dipper” (bu gang ta dou 步罡踏斗). (The Big Dipper is a group of seven bright stars of the constellation Ursa Major, also known as the Great Bear.)

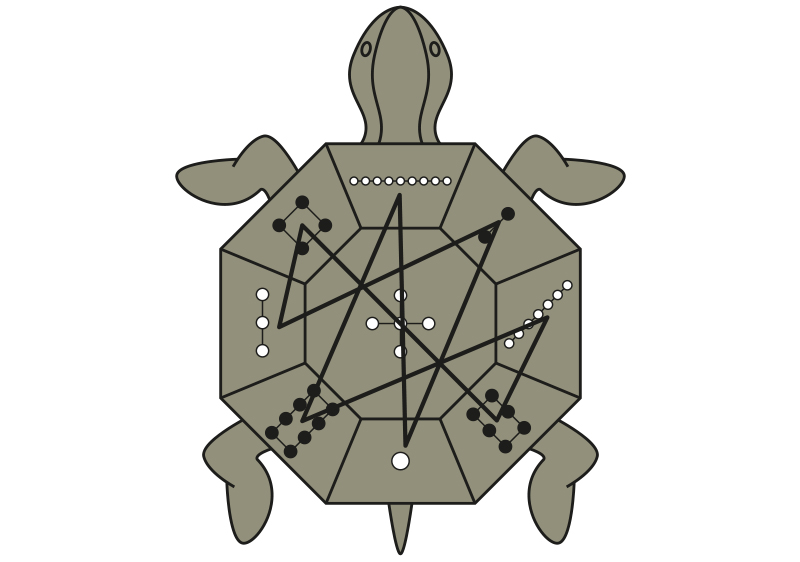

According to Chinese mythology, the Yu Step dates back some four thousand years. During a period of great flooding in China, Yu the Great, the mythological founder of the proto-Chinese Xia dynasty (2070–1600 BCE), received the Luoshu10 (洛书) – or magic map of the seven stars – from heaven. This map was imprinted on the shell of a turtle that had emerged from the Luo River (a tributary of the Yellow River). The Luoshu sets out the Eight Trigrams, or Bagua (八卦),11 surrounding a central number, in which all numbers connect into a pattern of zig-zag lines.

To combat the flood, Yu the Great performed a dance that traced this zig-zag pattern for 13 years without stopping until he eventually defeated the flood demons. In the process, Yu became lame but he persevered until his task was completed.12

While in a trance, the tangki performs the zig-zag stagger of the Yu Step. During the dance, the tangki steps out with one foot (say the right foot) and then moves his left foot forward, touching the toes of this foot against the heel of the right without any transfer of weight. The left foot then steps out, and the right foot is brought forward to meet it. The Tangki also sometimes hops on one foot.

The Luoshu, or magic map of the seven stars, that Yu the Great found imprinted on the shell of a turtle emerging from the Luo River. The Luoshu sets out the Eight Trigrams surrounding a central number where all numbers connect into a pattern of zig-zag lines. To defeat the flood demons, Yu the Great danced according to this zigzag pattern for 13 years. While in a trance, the tangki performs this zig-zag dance choreography known as the Yu Step.

The Luoshu, or magic map of the seven stars, that Yu the Great found imprinted on the shell of a turtle emerging from the Luo River. The Luoshu sets out the Eight Trigrams surrounding a central number where all numbers connect into a pattern of zig-zag lines. To defeat the flood demons, Yu the Great danced according to this zigzag pattern for 13 years. While in a trance, the tangki performs this zig-zag dance choreography known as the Yu Step.

Tangki Self-mortification

One of the more dramatic elements of tangki spirit-medium worship is self-mortification, or self-wounding, specifically by cutting the body with swords or mace-like weapons. Tangki may also have their flesh pierced with rods, swords and skewers while in a state of trance.

Worshippers believe that cutting the body spills the tangki’s blood, which can then be used to exorcise malevolent spirits. The blood is smeared onto talismans which are taken home by devotees to affix on their front doors as protection against evil spirits.

Although tangki can be physically injured, they derive power from being pierced with weapons and skewers. It is believed that inherently aggressive spirits reside in weapons as such instruments are created specifically for the purpose of maiming or killing. During self-mortification, as the tangki is pierced or cut by the weapon, the god that possesses the tangki becomes supercharged by the aggressive spirit of the weapon.

There is also symbolism in the various forms of self-mortification. Some tangki will have five skewers driven into their backs, which fan out over their shoulders. These rods represent the Celestial Armies of the Five Directions. Each army is represented by a different flag colour: the army of the East is represented by the blue or green flags; the South army uses the red flag; the white flag symbolises the West army; while the North army uses the black flag. The yellow flag, on the other hand, represents the Central army.13

The weapons can transmit the power of the five armies if they are topped with the carved wooden godheads of the five generals commanding these celestial forces. Bristling with pierced skewers and waving a sword or spear, the tangki goes around exorcising evil from the precinct.

The five skewers running through the back of the tangki represent the Celestial Armies of the Five Directions. Photo courtesy of Victor Yue. First used in Chan, M. (2014). Tangki War Magic: The Virtuality of Spirit Warfare and the Actuality of Peace. Social Analysis, 58 (1), 25–46. Retrieved from Singapore Management University website.

The five skewers running through the back of the tangki represent the Celestial Armies of the Five Directions. Photo courtesy of Victor Yue. First used in Chan, M. (2014). Tangki War Magic: The Virtuality of Spirit Warfare and the Actuality of Peace. Social Analysis, 58 (1), 25–46. Retrieved from Singapore Management University website.

A Singaporean Tangki

One of Singapore’s most respected tangki was Tan Ah Choon (陈亚春), who died in 2010 at the age of 82.14

Born in Singapore in 1928, Tan became a medium in his early 20s, after the deity Tiong Tan (Zhong Tan Yuan Shuai 中坛元帅) appeared to him in a dream. Tan went to the Hui Hian Beo temple (Fei Xuan Miao 飞玄庙) in Bukit Ho Swee to learn how to become a medium and he eventually served the deity Siong De Kong (Shang Di Gong 上帝公, also known as Xuan Tian Shang Di 玄天上帝), among the highest gods in the Chinese pantheon.

Tan was at the height of his powers in the 1960s and was regarded then as the “wisest, most powerful spirit-medium in the Singapore tangki community”. He was given the moniker “Tangki Ong”, the King of Spirit Mediums.

Mr Tan Ah Choon (陈亚春) with a skewer through both cheeks, c. 1960s. Tan was regarded as the “Tangki King”, the most respected tangki in Singapore at one time. Photo taken in Singapore and provided by his family. First used in Chan, M., & Yue, V. (2010, July). Tan Ah Choon: The Singapore ‘King of Spirit Mediums’ (1928–2010). South China Research Resource Station Newsletter, 60 (15), 1–4, p. 4. Retrieved from Singapore Management University website.

Mr Tan Ah Choon (陈亚春) with a skewer through both cheeks, c. 1960s. Tan was regarded as the “Tangki King”, the most respected tangki in Singapore at one time. Photo taken in Singapore and provided by his family. First used in Chan, M., & Yue, V. (2010, July). Tan Ah Choon: The Singapore ‘King of Spirit Mediums’ (1928–2010). South China Research Resource Station Newsletter, 60 (15), 1–4, p. 4. Retrieved from Singapore Management University website.

Tangki in Singapore typically hold regular jobs in addition to working as spirit-mediums, and Tan was no exception. He started out as a pirate taxi driver before eventually driving buses and, at one point, a fire engine. Tan worked during the day and held consultations at night. During such sessions, Tan would either fall into a trance to become the deity-incarnate, or he would channel the spirit of the deity into a palanquin that would rock violently when carried by helpers. The heavy chair needed four people to lift and stabilise it.

Tan was also sought after as a “piercer”, i.e. the person who drives the long skewers and rods into the bodies of the tangki when they are possessed. Standing on a chair, Tan and two other men would drive the skewers into the flesh of the tangki in one clean movement.

In Singapore, tangki worship practices flourish as small cults centred around charismatic individuals such as Tan. They operate as informal groups to celebrate the feast days of their respective deities. However, after the passing of the tangki, the group will often break up.

Tangki usually operate independently of Chinese temples as the latter are mostly run by management committees made up of local businessmen who generally do not want interference from individuals who purport to speak as gods. However, this does not preclude the occasional collaboration at festivals.

While it might appear that tangki events are on the decline, compared with the situation decades ago, younger tangki are still appearing on the scene to take on the mantle (and skewers) of the older generation. They include people like Tan Eng Hing, a 51-year-old medium who started going into trances when he was just 16. When possessed, he channels Shan Cai Tong Zi (善才童子), the child god of wealth whose Sanskrit name is Sudhana.15 Tan holds his consultations at Chia Leng Kong Heng Kang Tian (正龙宫玄江殿) temple at 85 Silat Road. He is also an expert in Chinese astrology known as bazi (八字) and fengshui (风水).

Tan Eng Hing started going into trances when he was just 16. When possessed, he channels Shan Cai Tong Zi (善才童子), the child god of wealth whose Sanskrit name is Sudhana. Photo taken by Victor Yue in Singapore, 2012.

Tan Eng Hing started going into trances when he was just 16. When possessed, he channels Shan Cai Tong Zi (善才童子), the child god of wealth whose Sanskrit name is Sudhana. Photo taken by Victor Yue in Singapore, 2012.

Tangki Practices Across Asia

Thanks to immigration from the Minnan region of China into Southeast Asia, tangki practices can also be found where migrant Chinese communities have a significant presence. These include parts of Thailand and Indonesia.

Phuket, Thailand

The Chinese in Phuket are mainly descendants of Fujian migrants who arrived in the region in the 19th century and worked as tin miners.16 In Phuket, an important occasion for tangki worship is the Nine Emperor Gods Festival which is also celebrated in many parts of Southeast Asia, including Singapore. As the festival runs from the eve of the ninth lunar month to the ninth day of the month, it is also known as the double-nine celebrations. During this period, devotees abstain from meat for nine days, which is why the festival is sometimes referred to as the Vegetarian Festival.

On the first day of the festival, i.e. the last day of the eighth lunar month, temple elders go out to sea in a boat, carrying with them a giant censer. At sea, the spirits of the star gods (of the Big Dipper) will possess the censer. When the censer is brought back, it is placed on a palanquin to be borne to the temple. A number of strong men are needed to carry the sedan chair because the spirits in the censer will violently rock the chair, pushing the men in different directions and even causing them to spin in circles. The festival of the Nine Emperor Gods culminates in a great procession on the ninth day of the ninth month.

In Phuket, this festival has gained notoriety for the spectacular displays of tangki self-mortification. Thai masong parade through the streets of old Phuket town with all manner of objects pierced through their cheek: a standing fan; a giant parasol; two petrol pump dispensers with one spout in each cheek; a large toy wooden boat; and even an entire bicycle with the shaft driven through the cheeks. The masong are seen as self-sacrificing gods who endure pain in order to transfer good karma to the community.

Singkawang, West Kalimantan

Singkawang is the second-largest town in West Kalimantan on the island of Borneo. It is an enclave of descendants of Hakka immigrants who arrived in the 18th century to work as gold miners.17 On the 15th day of the Lunar New Year (known as Imlek in Indonesia), around 300 to 500 spirit-mediums will parade on the main streets of Singkawang. The spirit-mediums, known as tatung, or Lao Ye (老爷), are carried through the streets of the town on wooden palanquins with special chairs.

A tatung possessed by the spirit of a Chinese soldier rides on a knife palanquin. Walking alongside are other Chinese and Dayak mediums dressed as Malay, Dayak and Chinese spirit-warriors. Photo taken by Margaret Chan in Singkawang, 2008.

A tatung possessed by the spirit of a Chinese soldier rides on a knife palanquin. Walking alongside are other Chinese and Dayak mediums dressed as Malay, Dayak and Chinese spirit-warriors. Photo taken by Margaret Chan in Singkawang, 2008.

The Singkawang spirit-mediums are possessed by earth gods, i.e. the spirits of ancestors who lived and died in the region. Walking alongside the palanquins are other Chinese and Dayak mediums dressed as Chinese, Dayak and Malay spirit-warriors. This parade of Chinese ancestor-spirits marching in brotherhood with Malay and Dayak ancestor-spirits demonstrates that the Chinese have a place among the indigenous spirits of Indonesia.18

China

In 2001, while on a field trip to Quanzhou, China, I met an elderly Chinese man who testified to the existence of tangki worship in China before the arrival of the Communists.

The man lived in the shadow of the main Tiangong temple in the city. Tangki used to visit the temple on feast days and my interviewee revealed how wild-eyed tangki, in hot pursuit of unseen demons, would burst into his house uninvited.

In the late 19th century, tangki worship began to lose favour in China as Western science became entrenched among the intelligentsia in China, and folk beliefs were regarded as superstition.19 The Nationalist and Communist governments of the 20th century further worked to rid Chinese society of these religious practices.

The reforms initiated by President Deng Xiaoping in 1978, however, permitted a revival of community temples. These are now visited by tangki groups from Singapore, Malaysia and especially Taiwan, who gather in the city as part of their regular pilgrimages.

The elders of these Chinese temples enthusiastically put together processional parades of music bands, dancing women (made up of retired folk) and student marching groups to accompany the visiting deity in style. They charge for the service and in China today, these parades have become more important as a money-making venture rather than a religious practice.

Dr Margaret Chan is a retired associate professor of theatre and performance (studies) at the Singapore Management University, and has worked as a journalist and food critic. Also known as a stage and television actress, she played the titular role in the acclaimed play, Emily of Emerald Hill.

Dr Margaret Chan is a retired associate professor of theatre and performance (studies) at the Singapore Management University, and has worked as a journalist and food critic. Also known as a stage and television actress, she played the titular role in the acclaimed play, Emily of Emerald Hill.

NOTES

-

The Three Pure Ones (San Qing 三清) refer to the Daoist Trinity, the three highest gods in the Daoist pantheon. The three gods are Yuanshi Tianzhun (元始天尊), Lingbao Tianzhun (灵宝天尊) and Daode Tianzhun (道德天尊). ↩

-

The Five Celestial Armies or Five Celestial Camps represent the five cardinal directions: North, East, South, West and Central. The five generals of these armies are believed to have the ability to scare away demons and banish plague and evil spirits. ↩

-

See Mair, V. (2014, May 27). North, south, east, west. Language Log. Retrieved from Language Log website. ↩

-

Chan, M. (2014). Tangki war magic: The virtuality of spirit warfare and the actuality of peace. Social Analysis, 58 (1), 25–46. Retrieved from Singapore Management University website; Chan, M. (2016). Tangki war magic: Spirit warfare in Singapore. In D.S. Farrer (Ed.), War magic: Religion, sorcery, and performance (pp. 25–46). New York: Berghahn Books. (Not available in NLB holdings) ↩

-

Luo, G.Z. (1995). Three kingdoms (vols. 1–4). Beijing: Foreign Language Press. (Not available in NLB holdings) ↩

-

See Wu, C.E. (1993). Journey to the West. Beijing: Foreign Language Press. (Not available in NLB holdings) ↩

-

Xu, Z.L. (1992). Creation of the gods. (2 vols.). Beijing: New World Press. (Not available in NLB holdings) ↩

-

See Chapter twenty-five: The universal door of Guanshi Yin bodhisattva (The bodhisattva who contemplates the sounds of the world) (n.d.). Retrieved from buddhistdoor.com website. ↩

-

Webb, W. (2012, May 24). Tua Ji Peh: The intricacies of liminality in the deification of Chinese non-Buddhist supernatural beings in Chinese-Malaysian communities. ASIANetwork Exchange 19 (2), 4–13. Retrieved from Asian Network Exchange website. ↩

-

The Luoshu is widely used in Chinese geomancy and fengshui today. It is a three-by-three grid of dots representing the numbers one to nine. The numbers in each of the rows, columns and diagonals add up to 15 (which is the number of days in each of the 24 solar terms in the traditional Chinese calendar). ↩

-

The Eight Trigrams are eight symbols used in Daoist cosmology to understand the organisation of life and the universe. ↩

-

The legend of Yu the Great is popular folklore. Researchers have linked the story with a great flood of 1920 BCE which occurred when an earthquake caused a dam on the Yellow River to break. See Wu, Q.L. et al. (2016, August 5). Outburst flood at 1920 BCE supports historicity of China’s Great Flood and the Xia dynasty. Science, 353 (6299), 579–582. ↩

-

Also see earlier explanation in Note 2 on Celestial Armies. ↩

-

All information on Tan Ah Choon was obtained from Chan, M. & Yue, V. (2010, July). Tan Ah Choon: The Singapore ‘King of Spirit Mediums’ (1928–2010). South China Research Resource Station Newsletter, 60 (15), 1–4, p. 4. Retrieved from Singapore Management University website. ↩

-

Sudhana is an acolyte of Guanyin, the Bodhisattva of Compassion or Goddess of Mercy. Sudhana is a pious Indian pilgrim whose story is told in the Gandavyuha Sūtra, a 4th-century Mahayana Buddhist text. [See Fontein, J. (1967). The pilgrimage of Sudhana: A study of Gandavyuha illustrations in China, Japan and Java. The Hague and Paris: Mouton & Co. (Not available in NLB holdings.] Sudhana should not to be mistaken for The Little Red Boy (红孩儿), a character in the Chinese classic Journey to the West (西游记). The Little Red Boy is a demon who is subdued by Guanyin who renames him Sudhana and makes him an acolyte. Because of the popularity of Journey to the West, Sudhana tangki often have to point out that the deity who possesses them is the holy pilgrim, and not The Little Red Boy. ↩

-

Khoo, S.N. (2009). Hokkien Chinese on the Phuket mining frontier: The Penang connection and the emergence of the Phuket Baba community. Journal of the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, 82 (2) (297), 81–112. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website. ↩

-

About the Chinese in Singkawang, see Heidhues, M.S. (2018). Golddiggers, farmers, and traders in the “Chinese districts” of West Kalimantan, Indonesia. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. (Not available in NLB holdings) ↩

-

Chan, M. (2009). Chinese New Year in West Kalimantan: Ritual theatre and political circus. Chinese Southern Diaspora Studies, 3, 106–142. Retrieved from Singapore Management University website; Chan, M. (2013). The spirit-mediums of Singkawang: Performing ‘peoplehood’. In S.M. Sai & C.Y. Hoon (Eds.), Chinese Indonesians reassessed: History, religion and belonging (pp. 138–158). London, New York: Routledge. (Call no.: RSEA 305.89510598 CHI) ↩

-

Huang, K.-W. (2016). The origin and evolution of the concept of mixin (superstition): A review of May Fourth scientific views. Chinese Studies in History, 49 (2), 54–79. Retrieved from Taylor & Francis Online. ↩