The Plague Fighter: Dr Wu Lien-Teh and His Work

The Penang-born doctor helped eradicate the deadly Manchurian pneumonic plague of 1910 and pushed for the use of face masks to prevent its spread. Kevin Y.L. Tan documents his life and work.

Dr Wu Lien-Teh working with a microscope in his first plague laboratory in Harbin, China, 1911. Wu Lien-Teh Collection, PictureSG, National Library, Singapore.

Dr Wu Lien-Teh working with a microscope in his first plague laboratory in Harbin, China, 1911. Wu Lien-Teh Collection, PictureSG, National Library, Singapore.

The year 2020 will be remembered as the time when the Covid-19 pandemic struck. As the virus spread through towns and cities, people were made to isolate themselves, to work from home and to don face masks when they went out.

Although few realise it, much of this is a replay of some of the protocols that were pioneered 110 years ago by a brilliant but now-forgotten Penang-born bacteriologist Wu Lien-Teh (伍連德) when he was tasked to deal with the Manchurian pneumonic plague of 1910–11. Wu’s efforts gained him the reputation and sobriquet “The Plague Fighter”.1

The Making of a Modern Chinese Doctor

Born in Penang on 10 March 1879, Wu was the fourth son of Ng Khee-Hock (1832–1916) and Lam Choy-Fan (1844–1908). Ng was an immigrant from Taishan in Guangdong province, China, while Lam was a Penang-born Hakka. Although Wu’s Cantonese birth name was Ng Leen Tuck, he was officially registered as “Gnoh Lean Tuck” by a school clerk who transliterated his name into Hokkien.2 Wu was known by this name until 1908 when, upon arrving in Tianjin, China, he had it transliterated into Mandarin as Wu Lien-Teh. (When Wu was studying in Cambridge though, he was known as G.L. Tuck as the English mistook his personal name for his surname).3

In 1886, at the age of seven, Wu enrolled at the Penang Free School. Seven years later, he sat for the first of his four attempts at the Queen’s Scholarship examination. In 1896, the 17-year-old was finally awarded the scholarship and became only the third student from the Penang Free School to bag this prestigious honour.4

Scholarship in hand, Wu entered Emmanuel College in Cambridge where he continued to excel. In 1898, he was awarded the “Exhibition” (scholarship) in Natural Science at the college, which earned him a stipend of £40.5 Reporting this news, The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser speculated that Wu was the first Straits student at either Oxford or Cambridge to attain the status of “Exhibitioner”.6

In his third year, Wu obtained a First Class in his Bachelor of Arts final examination (which he had to take before studying for his medical degree in Cambridge) and was made a Foundation Scholar with a stipend of £60. Thereafter, he won one of two university scholarships offered by St Mary’s Hospital in Paddington, which came with a £150-scholarship prize that was enough to cover his hospital training fees for three years. Wu was the first Chinese student to be accepted by St Mary’s where he won a series of prizes: the Special Prize in Clinical Surgery (1901), the Kerslake Scholarship in Pathology (1901) and the Cheadle Gold Medal for Clinical Medicine (1902).7

Upon completing his three-year clinical training in 1902, Wu obtained a House Physicianship at the Brompton Hospital for Consumption and Diseases of the Chest.8 At Brompton, he received news from Emmanuel College that he had been awarded a Research Studentship, valued at £150 a year, to undertake postgraduate work at a research institute in either England or continental Europe.

Wu spent the last four months of 1902 at the Tropical Diseases Institute in Liverpool. At the end of his stint, Wu completed his final examination for his Bachelor of Medicine and Bachelor of Surgery degrees. At his oral examination, Clifford Allbutt, Regius Professor of Medicine at Cambridge University, advised Wu to make good use of his forthcoming research stint in Europe and to submit it for the degree of Doctor of Medicine (MD).9

In 1903, Wu spent eight months in Germany’s University of Halle (today’s Martin Luther University of Halle-Wittenberg), under the supervision of the famous German bacteriologist Professor Karl Fraenkel, and then at the Institut Pasteur in Paris under Professor Ellie Metchikoff. Wu then returned to Cambridge University and worked on his doctoral thesis which he submitted to Professor Allbutt in August that year.

Wu successfully defended his thesis and, at age 24, had done everything necessary to fulfill the requirements for his MD degree. However, as university regulations stipulated that there should be a minimum of three years between the initial medical degrees and the MD degree, Wu was only conferred the latter two years later in absentia in 1905.

Meanwhile, Wu expressed interest in working for the Colonial Medical Service but was informed by the Colonial Office that he would only be accepted as an “Assistant Medical Officer” and not as a “Medical Officer”, as the latter post was reserved for “Britishers of pure European parentage, whatever the qualification”.10 Incensed, Wu decided to accept another Research Studentship from Emmanuel College to pursue a further year of research into tropical diseases at the newly established Institute for Medical Research in Kuala Lumpur.

In 1903, Wu returned to Malaya, stopping by Singapore for a week before travelling to Penang to visit his parents whom he had not seen in almost seven years. He then headed to Kuala Lumpur where he undertook research into beri-beri as the institute’s first research student.11 On completing his fellowship at the end of 1904, Wu returned to Penang and established a private medical practice on Chulia Street that became very popular.12

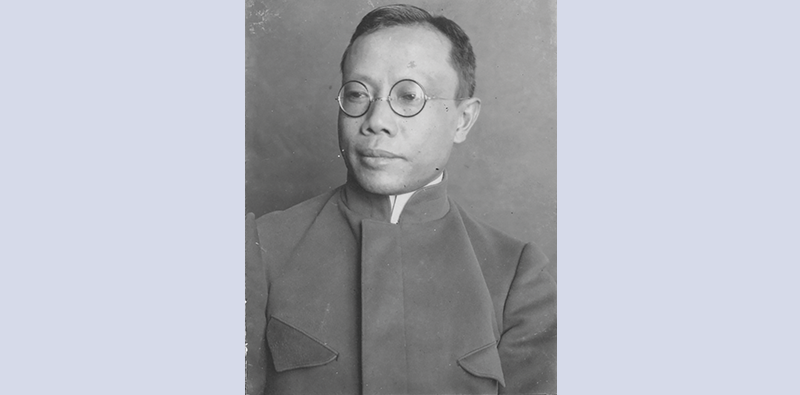

Dr Wu Lien-Teh, at age 41, taking charge of anti-plague work during the second pneumonic plague epidemic in Manchuria, c. 1920. Wu Lien-Teh Collection, PictureSG, National Library, Singapore.

Dr Wu Lien-Teh, at age 41, taking charge of anti-plague work during the second pneumonic plague epidemic in Manchuria, c. 1920. Wu Lien-Teh Collection, PictureSG, National Library, Singapore.The Wu Lien-Teh Collection in the National Library has over 840 photographs that mainly document Wu’s work and achievements in Manchuria and China, including his efforts to contain the pneumonic plague of 1910–11 and 1920–21. In addition, there are photographs of his family and friends.

The photographs of Manchuria and China capture grim scenes such as unburied bodies left out in the open, mass cremation of corpses, and the isolation and protective measures adopted to curb the spread of the plague. These were likely to have been taken and captioned by Wu himself. It is not known who took the photographs of Wu with his family, friends and colleagues.

These photographs came from two separate donations. In 2010, Wu’s eldest daughter, Dr Betty Wu Yu-lin, gave three photo albums to the National Library as well as individual photographs. The three albums are titled Plague and Medical Scenes: Manchuria and China, 1911, 1921 up to 1936; Chronological Record of Anti-plague Work in Manchuria and China, 1910–1937; and Ruth’s Complete Collection, 1910 to 1935. In 2018, the National Library received another 35 photographs from Dr Wu’s grandson, Daven Wu. The photographs have been digitised and can be accessed on the National Library’s PictureSG portal.

The Wu Lien-Teh Collection also includes publications by Dr Wu, such as League of Nations Health Organisation: A Treatise on Pneumonic Plague; History of Chinese Medicine; The Queen’s Scholarships of Malaya, 1885–1948; and Plague Fighter: The Autobiography of a Modern Chinese Physician; two typescript manuscripts; and a set of compiled genealogy of the Wu surname, which traces it back to Lingnan in China (岭南伍氏阖族总谱).

Social Causes and the Anti-Opium Movement

Although Wu only spent a week in Singapore en route to Penang in October 1903, it was a period that would have a big impact on his life. He stayed with Lim Boon Keng13 – also a medical doctor and Singapore’s first Queen’s Scholar – who initiated Wu “into the need for devoting some time to social service among the people”.14 At Lim’s home, Wu met the “most charming and beautiful” Ruth Huang – the younger sister of Lim’s wife Margaret. She reciprocated his affections and the couple married in July 1905.

Apart from his flourishing medical practice in Penang, Wu also played a “prominent part in the social service work, and tried hard to introduce reforms among the people, such as girls’ education, removal of the queue [pigtails for men], campaign against gambling and opium smoking, formation of literary clubs and promotion of healthy physical exercises among boys and girls”.15

In 1906, Wu plunged himself “heart and soul into the anti-opium campaign” after reading that the British parliament had denounced the opium trade and requested the British government “to take such steps as may be necessary for bringing it to a speedy close”.16 In March that year, Wu organised the first-ever Anti-Opium Conference for the Straits Settlements and Federated Malay States, which was held in Ipoh.17

Unfortunately, the official rhetoric on stopping the opium trade had not yet percolated to the colonies. Officials in Malaya still supported the trade in opium and continued issuing licences for its sale. In retaliation, the Penang authorities decided to teach Wu a lesson by prosecuting him for unlicensed opium possession. In 1906, a staged “raid” was organised by no less than the Senior Medical Officer of Penang, Dr Sidney Lucy. Wu had purchased a single ounce of opium from the previous owner of the dispensary, but had never sold nor dispensed it. He was charged with possessing opium without a requisite licence and was fined $100 by the District Court. His conviction was subsequently upheld by the Supreme Court.

Dr Wu Lien-Teh (standing, extreme right) in a family portrait with his parents, four brothers and three nephews, 1903. He had just returned from England. Wu Lien-Teh Collection, PictureSG, National Library, Singapore.

Dr Wu Lien-Teh (standing, extreme right) in a family portrait with his parents, four brothers and three nephews, 1903. He had just returned from England. Wu Lien-Teh Collection, PictureSG, National Library, Singapore.

The First Plague Epidemic, 1910

At the time of Wu’s troubles with the Penang authorities, he received two invitations: the first from London to attend an anti-opium meeting at the Queen’s Hall and the second from General Yuan Shih-Kai, Grand Councillor (and later President) of the Chinese government in Peking (Beijing), who offered him the post of Vice-Director of the Imperial Medical College in Tianjin.18 Although Wu was only 29 years old at the time, he felt that he was at a major crossroads in his life:

“Should I remain on the inhospitable shores of my birthplace where neither government nor friends seemed to need me, or should I accept the invitation, so opportunely offered, to render useful service to China where, at least, I would not be misrepresented and where I might find a fertile soil for promoting the scientific and health work which I had taken such pains to acquire before and since graduation.”19

Wu decided to accept both invitations. He set off for London and then went on a three-month tour of Europe. Upon his return to Penang, Wu resumed his practice but by May 1908, he and his family had set sail for China. Wu could hardly speak any Mandarin then as his education had wholly been in English, but he was a fast learner and very quickly picked up a working knowledge of the language, just as he had picked up French and German in the eight short months he worked in Europe.

By Wu’s own admission, the first few years of his stay in Tianjin “was not all too invigorating”,20 but this was to change in December 1910 when he received an unexpected telegram summoning him to the Foreign Ministry. Wu learned that there had been a deadly epidemic in Harbin and they needed an expert on bacteriology to “proceed to that region to investigate the cause and to suppress it, if possible”.21

A few months before, reports had reached Peking of a mysterious illness afflicting the people of Fuchiatien, the Chinese sector of the half-Russian town of Harbin in Northern Manchuria. Those who contracted the disease developed high fever, a cough with blood-streaked sputum and purplish discolouration of the skin. Almost all who were afflicted died within a few days. The Foreign Ministry feared that if the Qing court failed to stop the spread of the disease, the Russians and Japanese would take matters into their own hands and send in their own medical personnel to deal with the contagion.22

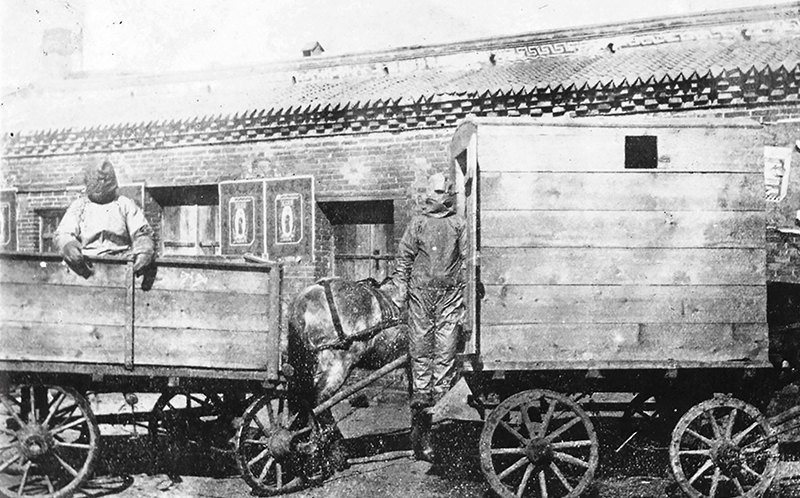

Horse carts transporting corpses to the cremation ground in Fuchiatien, Harbin, 1911. China’s first outbreak of the deadly pneumonic plague occured in this remote northern Manchurian region. Wu Lien-Teh Collection, PictureSG, National Library, Singapore.

Horse carts transporting corpses to the cremation ground in Fuchiatien, Harbin, 1911. China’s first outbreak of the deadly pneumonic plague occured in this remote northern Manchurian region. Wu Lien-Teh Collection, PictureSG, National Library, Singapore.

Wu and his assistant arrived in Harbin on Christmas Eve, 1910. The situation was grim: temperatures were minus 30 degrees, the city had just two doctors and five dressers for a population of 24,000, and dead bodies littered the streets, making the primitive unsanitary conditions of the town even worse. Russian doctors suspected bubonic plague (which is spread by infected flea bites) and examined patients without a mask. They soon contracted the disease as well.

The families of victims were unwilling to provide bodies of their loved ones for a post-mortem because of the Confucian tradition of mourning and burying the dead. The opportunity arose on his third day in Harbin when the Japanese wife of a Chinese innkeeper died and Wu was able to perform a preliminary post-mortem. He found the presence of the plague bacterium Yersinia pestis and evidence that it was a pneumonic plague (spread through the air by human hosts). Knowing that the disease was highly contagious and could spread from person to person through the inhalation of the bacterium, Wu formulated a strategy to control its spread. He had to do this quickly because many people were preparing to return from the city to their villages for the upcoming Lunar New Year, which would cause a further spread of the disease.

To keep the infected away from others, disused schools, warehouses and other facilities like train cars were turned into isolation facilities. In addition, a new plague hospital was built while the old one was burnt down. Wu also recommended the use of face masks so that people could protect themselves and others from the infection.

Initially, Wu’s plan met with opposition. Dr Gerald Mesny, a French professor at the Peiyang Medical College in Tianjin – who had experience dealing with the bubonic plague – insisted on being put in charge of operations. Mesny cast aside Wu’s plan with typical colonial arrogance. When Wu paid him a courtesy call and sat quietly, “trying to smile away their differences”, the Frenchman yelled threateningly, “You, you Chinaman, how dare you laugh at me and contradict your superior.”

Two horse-drawn wagons used as ambulances during the pneumonic plague epidemic that started in Harbin, China, in 1911. The covered one on the right is for the sick, while the unsheltered one is for those who had come into contact with the sick. Wu Lien-Teh Collection, PictureSG, National Library, Singapore.

Two horse-drawn wagons used as ambulances during the pneumonic plague epidemic that started in Harbin, China, in 1911. The covered one on the right is for the sick, while the unsheltered one is for those who had come into contact with the sick. Wu Lien-Teh Collection, PictureSG, National Library, Singapore.

Wu reported the encounter and tendered his resignation, but the authorities asked him to stay while they suspended Mesny’s services. Unfortunately for Mesny, his failure to correctly diagnose the disease cost him his life. Thinking that it was another type of bubonic plague, Mesny went about examining patients without a mask. As a result, he caught the pneumonic plague and died six days later.23 Suddenly, everyone wanted the simple cotton and gauze mask that Wu had used and recommended. Volunteers were soon producing them by the thousands.

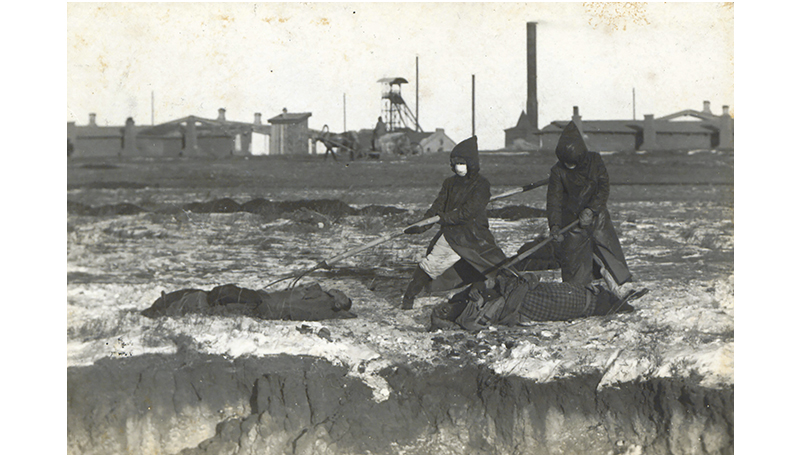

Despite all the isolation and movement controls enforced by military troops, the infection and mortality rates continued to rise throughout January 1911. In addition, there was another problem in Harbin: dead bodies were piling up because the ground had frozen solid to a depth of two metres, making burial impossible.

In late January, when Wu visited the burial ground, he found rows of corpses and coffins a mile long, all unburied. This presented him with a most difficult and delicate situation. If the corpses were left unburied, they would pose a huge health risk in the coming spring when rats would gnaw at the infected decomposing bodies and spread the infection further. The only way to quickly dispose of the corpses was to organise a mass cremation, but that would go against the tenets of Confucianism in a country where ancestor worship and visiting ancestral tombs had been viewed as an act of filial piety for centuries.

However, Wu managed to convince the local officials and a memorandum was sent to the Chinese emperor to approve their proposed action. Three days later, an imperial edict was handed down and on 31 January 1911 (the second day of the Lunar New Year), what is believed to be the first mass cremation in Chinese history was carried out in Harbin.

Eventually, the containment measures began to have an impact and mortality rates started falling almost immediately. By 1 March 1911, the last case of the plague in Harbin was registered. In other cities, the outbreak lasted another month before it was finally contained. In all, the epidemic affected an area that stretched almost 2,800 km from Manchuria to Peking, and reaching Zhili and Shandong provinces. It lasted seven months and claimed some 60,000 lives.

The Second Plague Epidemic, 1920

In 1912, Wu was made director of the newly set up North Manchurian Plague Prevention Service and he established a network of plague hospitals and laboratories throughout the region. As a result, he was prepared when a second major outbreak occurred in 1920.

The second plague began in October in the Hailar district of Manchuria and quickly spread through cities and towns in China’s north-east. Efforts by the Plague Prevention Service and local authorities eventually stopped the epidemic in October 1921, but not before 9,300 people had died.

During this outbreak, Wu himself went to affected areas to assess the situation and to make recommendations. In a paper published in The Journal of Hygiene in 1923, Wu wrote that when the outbreak first broke out in Hailar, he and his team had gone there in November 1920 where they noticed “the gradual evolution of the plague from the bubonic through the septicaemic into the pneumonic form, due principally to promiscuous spitting and huddling together of coolies day and night in unventilated inns”.24

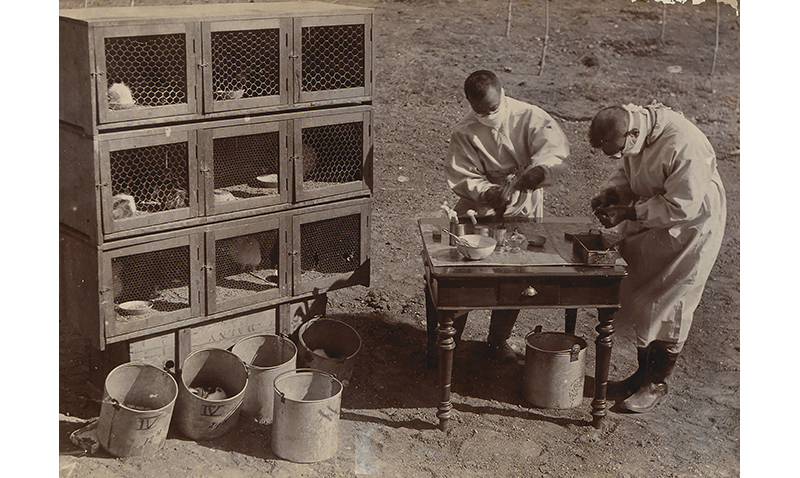

During the second pneumonic plague epidemic in Manchuria in 1921, Dr Wu Lien-Teh (left) and another doctor conducted experiments on animals like marmots to find out how the disease spread. In 1910, when the pneumonic plague outbreak first began, the initial victims of the disease were marmot trappers and fur traders in Manchouli (Manzhouli), along the Siberian border. Wu Lien-Teh Collection, PictureSG, National Library, Singapore.

During the second pneumonic plague epidemic in Manchuria in 1921, Dr Wu Lien-Teh (left) and another doctor conducted experiments on animals like marmots to find out how the disease spread. In 1910, when the pneumonic plague outbreak first began, the initial victims of the disease were marmot trappers and fur traders in Manchouli (Manzhouli), along the Siberian border. Wu Lien-Teh Collection, PictureSG, National Library, Singapore.

Wu also wrote about the non-medical difficulties that doctors faced. In the city of Harbin, rumours circulated that the plague hospital’s staff poisoned wells, flour and food in order to kill patients and earn the $3 they were paid for each dead body. In addition, he noted that the hospital “took in patients but did not let them out, and that something uncanny therefore happened within the hospital compound”.25 This suspicion made the lives of the doctors much harder. Wu wrote:

“For instance, the Chief Medical Officer was accused of shooting the sick in the plague compound and was threatened with a similar fate should an opportunity offer itself, our house-to-house inspection doctors were on several occasions faced with revolvers and knives in the course of their duty, while the disinfection assistants were almost obliged to swallow some of the disinfectants used in the disinfected houses.”26

Corpse collectors using long prongs to collect dead bodies during the second pneumonic plague epidemic in Manchuria, 1921. Wu Lien-Teh Collection, PictureSG, National Library, Singapore.

Corpse collectors using long prongs to collect dead bodies during the second pneumonic plague epidemic in Manchuria, 1921. Wu Lien-Teh Collection, PictureSG, National Library, Singapore.

Wu also met with resistance to mask-wearing among some medical personnel. When he visited the affected Manchouli (Manzhouli) region, he found a small Russian medical team there (half the region’s population was Russian). They were “most untrained, very careless about wearing masks in the presence of the sick and the dead” and even “smoked cigarettes while handling the dead”. Three nurses and 15 attendants from this team subsequently died from the plague. The Plague Prevention Service, on the other hand, suffered no fatalities.27

Wu himself was proud of the cotton and gauze masks he had popularised, and he noted that the service’s laboratory in Harbin also produced 60,000 face masks, in addition to their routine work.28

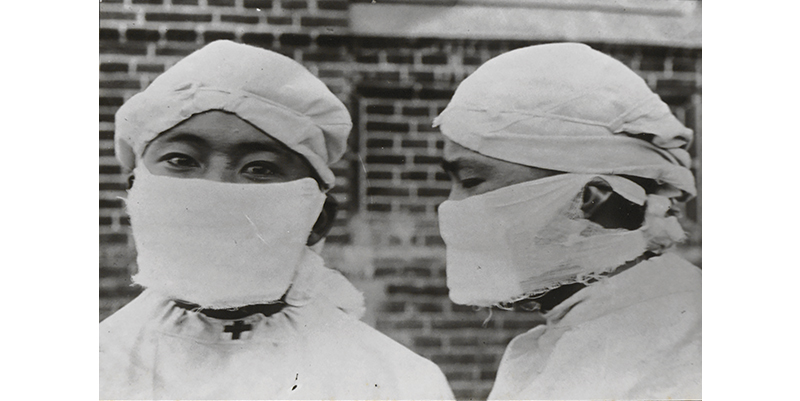

Demonstrating the correct way to wear cotton and gauze masks during the second pneumonic plague in Manchuria (1920–21). Wu Lien-Teh Collection, PictureSG, National Library, Singapore.

Demonstrating the correct way to wear cotton and gauze masks during the second pneumonic plague in Manchuria (1920–21). Wu Lien-Teh Collection, PictureSG, National Library, Singapore.

Father of Modern Chinese Medical Services

By now, Wu had become an important figure in the world of Chinese medical services.29 Following the first plague of 1910–11, he submitted a long memorandum on “Medical Education in China”, suggesting radical improvements to modernise the training of medical students. At Wu’s instigation, the government established the National Medical Association in 1915 to promote Western medicine in China. Wu was elected as its inaugural secretary and later served two terms as president from 1916 to 1920.

In 1930, the Chinese government created the National Quarantine Service and appointed Wu as its first director. Headquartered in Shanghai, this agency enabled the government to regain control of quarantine centres in China’s major ports that were previously under the supervision of foreign powers.

Wu was also responsible for initiating the building of modern Western-style medical facilities in China. The centrepiece of his efforts was the Peking Central Hospital to which he devoted his best efforts “unceasingly for four years, because it was intended as a model civil hospital”.30 Between 1912 and 1935, Wu was responsible for building 14 hospitals in various parts of the country.31

Dr Wu Lien-Teh in a studio portrait with his second wife Marie (his first wife passed away in 1937) and their children, 1949. Wu Lien-Teh Collection, PictureSG, National Library, Singapore.

Dr Wu Lien-Teh in a studio portrait with his second wife Marie (his first wife passed away in 1937) and their children, 1949. Wu Lien-Teh Collection, PictureSG, National Library, Singapore.

Wu’s Final Decades

In 1937, while Wu was in Java attending a medical conference, he received news that his Shanghai home had been destroyed by Japanese invaders. He decided not to return to China and resigned from his position as director of the National Quarantine Service. He also suffered a personal tragedy when his wife Ruth died in November that year. By January 1938, he was back in Malaya where he resumed private medical practice at the Boon Pharmacy in Ipoh – the town of his first anti-opium conference.32

Like most other Malayans, Wu suffered during the Japanese Occupation. But he was able to continue practising without too much trouble as he had been previously conferred an honorary doctorate by the University of Tokyo. He was friendly with many of the Japanese commanders who sought his medical services.

In 1943, Wu was kidnapped by guerrillas of the Malayan Communist Party and held for a ransom of $7,000. He was released only after the money was paid up. The Japanese authorities found out about the ransom payment and accused Wu of helping the anti-Japanese resistance movement. Fortunately, his life was spared as he was the attending physician to one of the Japanese officers in Malaya.

Wu finally retired from medical practice in 1957 at the age of 78. In mid-January 1960, he moved back to Penang where he was born but died a week later on 21 January 1960, after suffering a stroke.33 He was survived by his second wife, Marie, two sons and three daughters.

Wu gained great fame as a pioneering plague fighter and became the first Malayan nominated for the Nobel Prize in Medicine in 1935. It is ironic that his success was the indirect result of the systemic racism that he experienced. As a colonial subject, he was raised and nurtured to be among the best of the King’s Chinese (as the Peranakan, or Straits-born Chinese, were known) and, indeed, he had proven himself the equal of any doctor in the British Empire. Yet, colonial racism ensured that he would not receive his due. When he tried to spread the values he had acquired in England in Malaya, the authorities decided to teach him a lesson and marginalise him.

Malaya’s loss was, however, China’s gain. Wu left for China at a time when it was on the cusp of modernity. This was just after China’s defeat in the Sino-Japanese War of 1895 and the collapse of the modernising Self-Strengthening Movement that had started in 1861.34 The movement, which sought to modernise through “Western means” but with “Chinese minds”, was an effort to import Western technology, methods and institutions without a corresponding adoption of the thinking, morals or norms of the West. It took someone like Wu – an overseas Chinese person with a Western education – to show how it was possible to do this. Western medical methods were applied and institutionalised with a sensitivity to Chinese traditions. Limited as this movement was in the field of medicine, it nevertheless paved the way for the creation of a modern Chinese state.

Dr Kevin Y.L. Tan is Adjunct Professor at the Faculty of Law, National University of Singapore, and at the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies, Nanyang Technological University. He specialises in Constitutional and Administrative Law, International Law and International Human Rights. He has written and edited over 50 books on the law, history and politics of Singapore.

Dr Kevin Y.L. Tan is Adjunct Professor at the Faculty of Law, National University of Singapore, and at the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies, Nanyang Technological University. He specialises in Constitutional and Administrative Law, International Law and International Human Rights. He has written and edited over 50 books on the law, history and politics of Singapore.

NOTES

-

Wu, L.-T. (2014). Plague fighter: The autobiography of a modern Chinese physician. Penang: Areca Books. (Call no.: RSEA 610.92 WU) ↩

-

The first student from the Penang Free School to win the Queen’s Scholarship was Ung Bok Hoey, in 1893. He was followed by Koh Leap Teng in 1894. See Tan, C.L. (2016). Live free: In the spirit of serving (p. 166). Singapore: The Old Frees’ Association. (Call no.: RSING 371.0095951 TAN) ↩

-

Penang School. (1898, July 11). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, p. 11. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

See National Library Board. (2015, December 31). Lim Boon Keng written by Ang Seow Leng. Retrieved from Singapore Infopedia website. ↩

-

Wu, L.T. (1923, May). The second pneumonic plague epidemic in Manchuria, 1920–21. The Journal of Hygiene, 21 (3), 262–288, p. 264. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website. ↩

-

Wu, 1923, p. 275. ↩

-

Wu, 1923, p. 275. ↩

-

Wu, 1923, p. 271. ↩

-

Wu, 1923, p. 277. ↩

-

See Goh, L.G., Ho, T.M., & Phua, K.H. (1987). Wisdom and Western science: The work of Dr Wu Lien-Teh. Asia Pacific Journal of Public Health, 1 (1), 99–109. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website; Lee, K.H., Wong, T.K., & Ng, K.H. (2014, January). Dr Wu Lien-teh: Moderninsing post-1911 China’s public health service. Singapore Medical Journal, 55 (2), 99–102. Retrieved from Singapore Medical Journal website. ↩

-

Dr Wu Lien Teh retires. (1938, January 22). The Malaya Tribune, p. 12. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Dr Wu – plague fighter – dies, aged 81. (1960, January 22). The Straits Times, p. 7. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

See Qu, J. (2016, August). Self-strengthening movement of late Qing China: An Intermediate reform doomed to failure. Asian Culture and History, 8 (2), 148–154. Retrieved from ResearchGate website. ↩