Asthma, Amahs and Amazing Food

Irene Lim recalls herbal remedies, home-cooked meals and domestic servants in this extract from her memoir, 90 Years in Singapore.

Clockwise from the top: An amah with a close-up of her bun secured with a hairnet and pin. Amahs took vows of celibacy, pledging to remain unmarried for life. Kouo Shang-Wei Collection, PictureSG, National Library, Singapore; Irene Lim with a flying fox that her father caught on a hunting trip to Johor, 1934. Courtesy of Irene Lim; One of the Peranakan dishes that Ah Sam cooked for the family was nonya chap chye cooked with preserved brown soya bean paste. Photo from Shutterstock.

Clockwise from the top: An amah with a close-up of her bun secured with a hairnet and pin. Amahs took vows of celibacy, pledging to remain unmarried for life. Kouo Shang-Wei Collection, PictureSG, National Library, Singapore; Irene Lim with a flying fox that her father caught on a hunting trip to Johor, 1934. Courtesy of Irene Lim; One of the Peranakan dishes that Ah Sam cooked for the family was nonya chap chye cooked with preserved brown soya bean paste. Photo from Shutterstock.

Born in Kuala Lumpur in 1927, Irene Lim, née Ooi, has lived in Singapore all of her life except for the three years she spent in Penang during the Japanese Occupation. She attended Raffles Girls’ School in the 1930s and early 1940s. In 1948, she married Lim Hee Seng, an accountant, raised three daughters between the 1950s and early 1970s, and led an active, social life.

Irene’s memoir, 90 Years in Singapore,1 presents fascinating accounts of her childhood, growing-up years, marriage, and family life. The family’s routines and responses to daily and community happenings provide an intimate window into life as experienced by middle-class women at the time.

In this extract from her book, Irene recalls her family’s domestic helpers preparing herbal remedies for ailments such as asthma and eczema, and cooking delicious Cantonese and Peranakan dishes for the family. She also describes in vivid detail household habits and cultural practices, the various foods the family ate, and their relationship with the women who worked as servants in the household in the 1950s and 1960s.

Irene looking resplendent in the 1950s. Courtesy of Irene Lim.

Irene looking resplendent in the 1950s. Courtesy of Irene Lim.

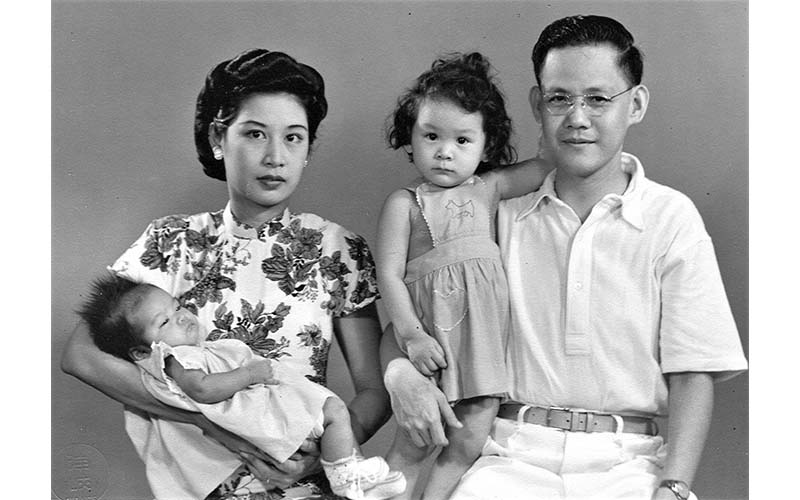

Irene with her husband Hee Seng, elder daughter Laurette and younger daughter Linda, 1950. Courtesy of Irene Lim.

Irene with her husband Hee Seng, elder daughter Laurette and younger daughter Linda, 1950. Courtesy of Irene Lim.

What I disliked about our neighbourhood was the sawmill at the corner of our road not far from our home,2 at the other end from the Chinese school. When the sawmill burned wood scraps, I feared that was a health hazard, and wondered if it worsened Cheryl’s3 asthma. To treat it, Ah Sam went to Chinatown to buy flying foxes to cook with herbs, which were supposed to “warm” a patient’s lungs; she told Cheryl it was mutton soup.

Cheryl also suffered very badly from eczema, for which mother-in-law4 took her to a sinseh at Upper Cross Street. He used herbs resembling dried twigs and leaves, which were boiled and then cooled until comfortably warm, for Cheryl to steep her affected hands in. Then she was bandaged with a thick white ointment which the locals insisted was made of frogs. They called it frog ointment. It took a long time but it did get rid of the eczema, which Western medicine could not.

Ah Sam with Cheryl at Sommerville Road, 1957. Courtesy of Irene Lim.

Ah Sam with Cheryl at Sommerville Road, 1957. Courtesy of Irene Lim.

Once in a while, a man would come around the neighbourhood with a very distinctive loud call that I could never make out, something that sounded like “way jerapan”. Ah Sam would dash out to buy bullfrogs from him to skin and then boil with herbs. The meat was white, like chicken, and of course Cheryl never found out what it really was. That was to cool her skin to get rid of the eczema. Ah Sam also bought small river turtles to steam for soup, saying it was good for the skin. She wanted to buy crocodile meat which was reported to be the best cure. I refused but now find that it is sold in NTUC FairPrice supermarkets!

I remember being told by another cook that asthma (or was it tuberculosis?) patients were cured by swallowing live, newborn mice whose eyes were not yet opened. It makes me sick to think of these tiny creatures wriggling inside the unfortunate patient’s throat down to the stomach.

Ah Sam (meaning “aunt” in Cantonese), whose given name was Lee Yuet Kiew (her friends called her Ah Kiew), came to work for us in 1954. Much later, she told us that she had left her home village in Guangdong province to come to Singapore because a fortune-teller warned her that if she had a husband, she would not have a son and vice versa, i.e., one of them would die.

So Ah Sam decided not to marry and like other members of her “black and white amah”5 sisterhood, she did not cut her hair. She always wore it in a single thick, long plait hanging down her back. On festive days, she would go to a hairdresser to have it combed into a “bun”, with a hairnet and some pins. Ah Sam and her “sisters” wore the same light-coloured Chinese cotton blouse (hip-length with a mandarin collar, diagonal front “frog” button closure, three-quarter sleeves and side slits at the hem) paired with loose black silk trousers daily. They wore the same outfit during festive occasions, only in a more elaborate and expensive material. They also wore gold and jade jewellery (earrings, bangles, chains and lockets) they had purchased with their wages.

Ah Sam belonged to the generation of Chinese women whose breasts were bound from puberty so that they would be flat-chested. This required the donning of a white chest undergarment with strings tied to flatten the breasts. I wonder if this contributed to her developing breast cancer later in life.

On her days off, Ah Sam visited her sisterhood’s premises in Chinatown, where some retired elderly amahs lived. There were also young girls they had “adopted” to care for them in their old age, in exchange for training in their service profession. Like her sisters, Ah Sam also belonged to a funeral association. In exchange for monthly or annual dues, the association would prepare and provide for the funerals of its members. Being single and far from home, these women would not have descendants to conduct funerary rites. Professional mourners were very common then and could be hired for any funeral. They wore sack cloth, chanted and banged cymbals and gongs while accompanying elaborately decorated hearses carried on the back of lorries. Family mourners walked or sat in cars behind the procession. I think some of the professional mourners belonged to martial arts associations.

When Ah Sam arrived as a sinkeh6 from China at the age of 18 (by Chinese reckoning), she found employment as a personal maid to one of Eu Tong Sen’s teenage sons at Eu Villa on Mount Sophia,7 next to the Methodist Girls’ School. She was very ambitious and, in her free moments, would steal off to the kitchen to watch the cooks prepare food. This was how she learned the art of fine Cantonese cooking even though she was from a peasant family.

Ah Sam was extremely intelligent. Although illiterate – she could not even recognise numbers and had to ask us to write down phone numbers for her – she had a remarkable memory. She could easily add and multiply, a skill which she was very proud of. She also took pride in working her whole life to support herself. She planned our meals and did most of the marketing at a wet market in Upper Serangoon or another one at Sennett Estate, going back and forth by bus and taxi. Ah Sam liked to go to the market every day to ensure we had fresh food, or perhaps to catch up on gossip. She went to Chinatown if special ingredients like dried mushrooms or herbs were needed for particular dishes. On her return, she would recite to me, by memory, the weight, price per unit weight, and total price of each of the 20-odd items purchased on a typical visit to the market, so I could do the accounts.

Our meals always included a soup (either abalone, lotus root, winter melon, etc.), fried or steamed fish (usually kurau, sek pan or pomfret, the last sometimes in a milk sauce), a meat dish and vegetables – all served on the rotating “lazy susan” atop our round dining table. Our girls got so spoilt that they protested if they had to eat the same dish too often. They also complained if they were fed “peasant dishes” that they didn’t like, Cantonese village classics like brown steamed rice with chicken and black mushrooms, and steamed egg-pie with minced pork and scallions. Another Cantonese dish Ah Sam cooked was steamed rice flavoured with Chinese sausages, liver sausages and a liver roll, which was liver encasing a thick piece of lard that had been preserved in sugar. Cheryl’s favourite was a dish of mixed vegetables and meat, chopped small and well seasoned, folded in a lettuce leaf and popped into the mouth, like the Vietnamese do.

Ah Sam had learnt to cook duck and salted vegetable soup, and chap chye the Peranakan way (with preserved brown soya bean paste, instead of preserved soya bean cubes as the Cantonese do). I also taught her another duck recipe: duck stuffed with chopped mushrooms, onions, minced pork and rice, seasoned and deep fried before being steamed. She also served preserved duck, either steamed or fried. Other specialities she made were steamed dim sum, steamed pigs’ brains to make the girls “brainy”, and steamboat served at home.

On special occasions, one or more of Ah Sam’s “sisters” would come over to help prepare special dishes like meat dumplings, or minced pork and crab meat balls cooked with bean threads in clear soup (bakwan kepiting). There were also baked crabs, whose shells were stuffed with minced pork, crab meat, diced mushrooms, large onions and water chestnuts, all well seasoned – with egg white added – before being placed in the oven. The crabs were bought live, trussed and hung up in strings in the kitchen until it was time to cook them; occasionally one would fall off and scurry about the kitchen floor.

Ah Sam also made traditional foods to be eaten on special days, such as the pink-and-white rice flour dumplings in a syrupy clear sweet sauce for the winter solstice. She also boiled dong guai,8 a bitter but expensive Chinese herb, in a pork-bone soup that the girls hated having to drink once a month after they began menstruating.

During the Chinese New Year, Ah Sam would gather the children in the front verandah, where she fired off Roman candles stuck at the end of one of the long bamboo poles we used for drying clothes. Since our house was on a hill slope, the candles had a nice, safe trajectory. Before fireworks were banned, the kampong across the narrow road would be noisy with them.

During the Eighth Moon (Mid-Autumn) Festival, we bought the children lanterns from Chinatown, made of coloured cellophane paper and wire bent in the shapes of various birds and animals, with a small candle inside. They would parade around the garden waving the lighted lanterns. The mooncakes we ate then were filled with black, red or brown bean paste (tau sah), sometimes with a salted egg yolk embedded. The children preferred these to the more elaborate mooncakes filled with different seeds and nuts that were sticky and hard to chew, but I liked the type with nuts better.

When it was the Fifth Moon (Dragon Boat) Festival, I would order special nonya choong (dumplings). These were different from the Cantonese dumplings which used fatty pork and a large piece of mushroom in each, covered in soaked but uncooked glutinous rice and then immersed in boiling water for four to four-and-a-half hours. We preferred the nonya dumplings that had minced streaky pork, pieces of minced, sugared wintermelon spiced with ground coriander, white peppercorns and chekur (aromatic ginger), plus shallots, garlic, sugar, salt, light and dark soya sauce, cooked together in lard. The meat filling was wrapped in a cone or pyramid of steamed glutinous rice, then placed inside bamboo leaves tied with hemp string and steamed for 35 minutes, never boiled. Both types of dumplings were very filling.

Glutinous rice and pork being scooped into bamboo leaves before being steamed. Nonya-style dumplings in the Lim household were stuffed with a mixture of minced pork cooked with candied wintermelon, ground coriander, white peppercorns and shallots, among other ingredients. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Glutinous rice and pork being scooped into bamboo leaves before being steamed. Nonya-style dumplings in the Lim household were stuffed with a mixture of minced pork cooked with candied wintermelon, ground coriander, white peppercorns and shallots, among other ingredients. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Two or three times when Ah Sam was working for us, which was about once in four or five years, she returned to China via Hong Kong to visit her family, often accompanied by one or more of her “sisters”. She would ask for our old things – clothes, shoes, toys – to take back with her for the children in the village. Between visits, she would mail them parcels as well as send letters dictated to a letter-writer in Chinatown.

It was from these visits in the 1950s and 1960s that we heard about how poor people were in China, how little food they had to eat during the Great Leap Forward,9 and how oppressive the Communist government was. Ah Sam and her “sisters” were all relieved that they had emigrated, and they regularly sent money home to their families.

During the Cultural Revolution,10 when I told Ah Sam the government had forbidden people from drinking tea, she replied that in her village they had been too poor to drink tea, which they grew only for export. Her family were farmers, and in Singapore, a male relative of hers used to collect “slops” from our kitchen to feed the pigs on his pig farm.

Ah Sam was our most loyal servant. She just knew “her” children – Laurette,11 Linda12 and Cheryl – were the cleverest ones around! But she was also difficult, insisting that she had to have full control of everything, including the other general household servants and the gardener, and that caused quite a bit of trouble. She left me once and came back again because I could not get any other servant to stay. She would ring these new hires to tell them she was such a good cook and that they would be no match for her. The last one to leave simply told me she wished to come back, but that no one else would work for me with Ah Sam around. In total, Ah Sam worked for me for 14 years.

Cheryl’s fourth birthday party at Sommerville Road, 1959. Standing behind Cheryl (seated in front of the cake) is Irene. Laurette is standing third from the left and Linda is standing at the extreme right looking down. Courtesy of Irene Lim.

Cheryl’s fourth birthday party at Sommerville Road, 1959. Standing behind Cheryl (seated in front of the cake) is Irene. Laurette is standing third from the left and Linda is standing at the extreme right looking down. Courtesy of Irene Lim.

During this time, we also had a string of other servants to take care of various household chores besides cooking. The two who stayed the longest were Ah Moy and Gek Lan (Ah Lan). Ah Moy came when she was 13 to help look after Cheryl and do odd jobs around the house. Ah Moy became Ah Sam’s servant, but Ah Sam did buy things for the girls who worked for us because they helped her to comb her hair or massage her.

Ah Moy was a farmer’s daughter and was filthy when I first saw her. Her feet were so caked with mud that we told her to use a brush to clean them. We taught her how to bathe properly. She had only used well water before so she was fascinated with the taps and played with them, especially the hot taps. Her mother took all her money and never bothered to leave food for her even when she knew Ah Moy would be returning home for a visit with her pay. I saved some money for Ah Moy and it did come in handy when she got married.

Ah Moy told us she could never settle back into her old home after living with us for some years, and had proper food and a clean bed with a mattress and sheets. When she was 16, her parents arranged for her to meet prospective bridegrooms and we were horrified that it became quite frequent. Each time Ah Moy was put “on show”, she was given a red packet of $12 if she was not deemed suitable by the bridegroom, and her parents happily pocketed the money. She was most upset and ashamed.

When Ah Moy got married, Ah Sam presented her with a bedspread and pillowcases, and we bought blankets from the money I had helped her save. I gave her a gold bracelet and bought a gold chain and pendant from the rest of the money, and even had some left over to buy makeup, the cheapest I could get. Her mother did nothing. On Ah Moy’s wedding day, I had to trudge to the farm to put her makeup on. We hoped she would find happiness, but a year or so later, Ah Moy turned up saying she was most miserable and that she did not have a good husband. But she later had a son, so perhaps things improved.

Ah Lan came next. Unlike Ah Moy who was illiterate, Ah Lan had left school at around 13 or 14 when she came to work for us. Her mother was a poor farmer’s wife who wished for a son but had a daughter every year until she had a round dozen, none of whom she loved. She would go to the market and let her children stand around while she had a bowl of noodles or some other titbit and not let them have a bite.

Ah Lan’s entire pay was also given to her mother so I had to save money for her to buy clothes. She was small and thin. Once, after her monthly visit home, Ah Lan cried and said that her elder sister objected to her working for us. The sister belonged to some group which at weekends met with “boys and girls in the same room”. They could have been left-wing Chinese school students, who were politically active at the time. Later, we realised that Ah Lan was stealing Laurette’s and Linda’s socks and panties, as well as Ah Sam’s cash, and even packets of Tide soap powder, perhaps instigated by her mother or sister, so we let her go.

Ah Peng was one servant with whom Ah Sam got on well. She was a big, fat jolly girl whom mother had found working as a hairdresser’s assistant. She had been paid $10 a month for three years and had not been given the training she had been promised. Instead, she swept the floors, and washed the towels and dishes. Ah Peng was under the charge of the Social Welfare Department as her mother worked in a gambling den at night and her father was in the mental hospital suffering from syphilis. Ah Peng did not know how to manage money and we tried to teach her not to blow all her pay at one go and also not to pick up taxi drivers as she liked to. One day, she told us she was getting married so we gave her presents and she left.

Irene at home in a photograph taken in early 2020 when she was 92 years old. Courtesy of Irene Lim.

Irene at home in a photograph taken in early 2020 when she was 92 years old. Courtesy of Irene Lim.

Irene Lim’s memoir, 90 Years in Singapore, is available for reference at the Lee Kong Chian Reference Library and for loan at selected public libraries (Call nos.: RSING 307.7609595 LIM and SING 307.7609595 LIM). It also retails at major bookshops in Singapore and online at www.shop.hoprinting.com.sg.

Irene Lim’s memoir, 90 Years in Singapore, is available for reference at the Lee Kong Chian Reference Library and for loan at selected public libraries (Call nos.: RSING 307.7609595 LIM and SING 307.7609595 LIM). It also retails at major bookshops in Singapore and online at www.shop.hoprinting.com.sg.

Irene Lim, who turns 94 years old this June, began documenting her life stories in 1989. Her daughter, University of Michigan professor Linda Lim, collected these and compiled them into a recently published book, 90 Years in Singapore.

Irene Lim, who turns 94 years old this June, began documenting her life stories in 1989. Her daughter, University of Michigan professor Linda Lim, collected these and compiled them into a recently published book, 90 Years in Singapore.

NOTES

-

Lim, I. (2020). 90 years in Singapore. Singapore: Pagesetters Services Pte Ltd. (Call no.: RSING 307.7609595 LIM) ↩

-

Irene’s home was on Sommerville Road, off Upper Serangoon Road. ↩

-

Cheryl is Irene’s youngest daughter, born in 1955. She attended Methodist Girls’ School, has a PhD in Sociology of Technology and lives in the United Kingdom. ↩

-

Irene’s mother-in-law, Lee Yew Teck, was born in Singapore in 1891 to China-born Christian parents. She attended Methodist Girls’ School and raised four children. ↩

-

These black-and-white amahs, or majie, hailed from the Pearl River Delta region of Guangdong province in China. In Singapore, they formed a tight-knit group and established clan associations in Chinatown. These hardworking and independent women took vows of celibacy and remained unmarried for life. ↩

-

Sinkeh means “new arrival” in Hokkien. ↩

-

Eu Tong Sen was a prominent businessman and community leader. He is best remembered as the man behind traditional Chinese medicine company Eu Yan Sang, which still exists today. Eu Villa, his lavish mansion on Mount Sophia, was designed by architectural firm Swan & Maclaren. ↩

-

Dong guai (Chinese angelica), also known as “female ginseng”, is a herb used in traditional Chinese medicine to treat menstrual cramps and other menopausal symptoms. ↩

-

The Great Leap Forward (1958–60) was a campaign mounted by the Chinese Communist Party to transform the country through forced agricultural collectivisation and rural industrialisation. ↩

-

The Cultural Revolution (1966–76) was launched by Mao Zedong in 1966 to reassert his control over the country. The masses were mobilised to purge all traces of capitalist and traditional elements in Chinese Communist society. ↩

-

Laurette is Irene’s eldest daughter, born in 1949. She attended Methodist Girls’ School. She graduated from the University of Singapore and lives in Singapore. ↩

-

Linda is Irene’s second daughter, born in 1950. She attended Methodist Girls’ School, has a PhD in Economics and lives in the United States. She is Professor Emerita of Corporate Strategy and International Business at the Stephen M. Ross School of Business, University of Michigan. ↩