Becoming Modern By Design

The now-defunct Baharuddin Vocational Institute was Singapore’s first formal school for design. Justin Zhuang looks at how the institute laid the foundation for the design industry here.

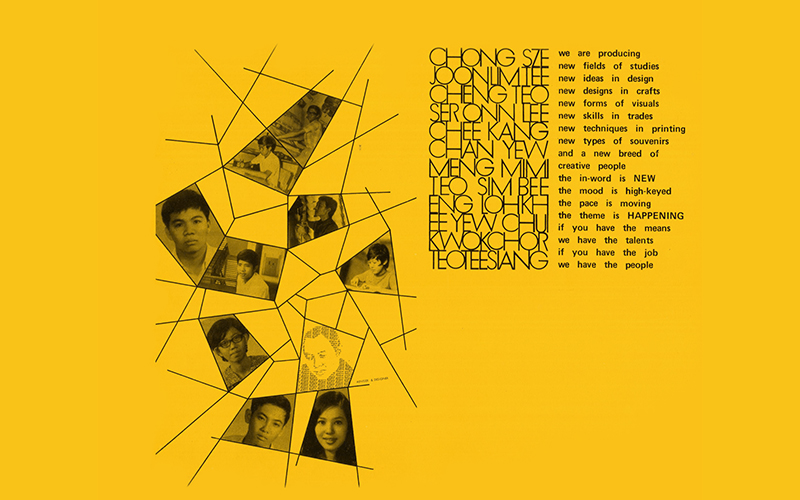

According to a manifesto by the editorial team of Baharuddin Vocational Institute’s 1971 commemorative magazine, the institute aimed to produce a “new breed of creative people”. Image reproduced from Baharuddin Vocational Institute. (1971). Singapore: Baharuddin Vocational Institute. (Call no.: RCLOS 372.95957 BVI).

According to a manifesto by the editorial team of Baharuddin Vocational Institute’s 1971 commemorative magazine, the institute aimed to produce a “new breed of creative people”. Image reproduced from Baharuddin Vocational Institute. (1971). Singapore: Baharuddin Vocational Institute. (Call no.: RCLOS 372.95957 BVI).

In the 1960s, most school crests in Singapore probably involved some combination of a torch with an open flame, an open book and a lion – all emblazoned on a shield with a motto below it.

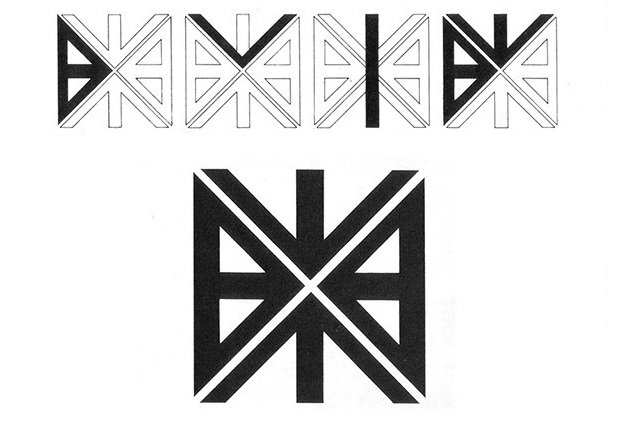

But Wee Chwee Beng, a pioneer teacher of Baharuddin Vocational Institute (BVI), ditched these hallmarks of Western heraldry when he designed a crest for the new institute in 1968. Instead of an illustrative approach, Wee abstracted the initials “BVI” into two right-angled arrows. Each was assembled by combining the letters “V” and “I”, while one was enclosed to form a triangle-like “B”. The arrows were constructed into a larger right-angled triangle that was inversely mirrored to form a square crest, which looked identical regardless of which side it was viewed from.

The design of the crest of Baharuddin Vocational Institute. The crest was an abstract combination of the letters “BVI”. Image reproduced from Baharuddin Vocational Institute. (1971). Singapore: Baharuddin Vocational Institute. (Call no.: RCLOS 372.95957 BVI).

The design of the crest of Baharuddin Vocational Institute. The crest was an abstract combination of the letters “BVI”. Image reproduced from Baharuddin Vocational Institute. (1971). Singapore: Baharuddin Vocational Institute. (Call no.: RCLOS 372.95957 BVI).

This design was too radical, even for his colleagues at Baharuddin. They found the abstract logo too modern for their liking. “I felt strongly at that point in time that we should break away from the norm or what is expected because I am designing for the future, not for the present, not for the past,” Wee explained. “At a time when others were drawing tigers and lions [on school crests], people were a bit shocked. I kept on trying to tell them it will be acceptable even 30 to 40 years on. I was saying this [design] would be modern and contemporary whereas if you start to have lions and tigers you are going back [in time].”1

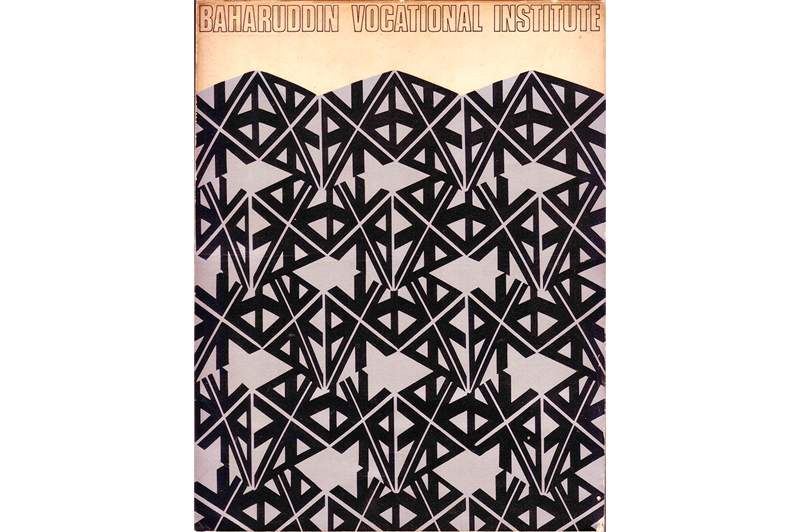

The cover of the commemorative magazine to mark the official launch of Baharuddin Vocational Institute in 1971. Image reproduced from Baharuddin Vocational Institute. (1971). Singapore: Baharuddin Vocational Institute. (Call no.: RCLOS 372.95957 BVI).

The cover of the commemorative magazine to mark the official launch of Baharuddin Vocational Institute in 1971. Image reproduced from Baharuddin Vocational Institute. (1971). Singapore: Baharuddin Vocational Institute. (Call no.: RCLOS 372.95957 BVI).

The eventual adoption of Wee’s progressive design was a fitting start for an institute set up to support Singapore’s rapid industrialisation programme. BVI was part of a network of vocational training institutes established by the government after Independence as part of a national industrialisation drive spearheaded by then Minister for Finance Goh Keng Swee.

At the time, the newly minted nation faced a raft of economic woes: the unemployment rate was high and many people were living in slums and squatter settlements. These vocational institutes2 were started with the objective of training a skilled workforce who could work in the new multinational companies and factories that the government was trying to attract to invest in Singapore.

The diverse curriculum from vocational institutes ranged from courses in mechanical engineering to building construction. BVI, however, specialised in the manual and applied arts, which included advertising art, handicrafts, fashion, furniture design and printing. Its graduates were expected to play a vital role in creating made-in-Singapore products, said then Minister of State for Education Lee Chiaw Meng at BVI’s first graduation ceremony on 7 November 1970:

“This institute was established with the realisation that the development of industries in Singapore requires a greater focus on design, product presentation, packaging, advertising and display and a growing printing industry. Furthermore, the expanding tourist trade planned for Singapore will inevitably generate a demand for handicrafts and souvenirs with a local flavour.”3

A National Design Institute

Prior to the establishment of the BVI, one typically entered such creative trades via an internship with companies or apprenticeship with artisans and practitioners. Studying art and design in prestigious overseas institutions was a privilege that only a select few enjoyed, who either paid the hefty school fees out of their own pockets or were awarded full scholarships. Although various private organisations in Singapore offered formal training in such fields, none seemed to be particularly successful.

The Nanyang Academy of Fine Arts – Singapore’s only art school then – had an Applied Arts Department since its founding in 1938, offering courses in calligraphy, graphic design, fabric design and illustration.4 However, it was primarily regarded as a school for artists rather than one that trained skilled workers for the manufacturing and industrial sector.

The Singapore Commercial Art Society (now defunct), which represented artists working in the advertising industry, pioneered a two-year commercial art course taught by members in 1970. Unfortunately, the take-up rate was low and there was a hiatus of six years before the next run of the course began in 1976.5

The government’s foray into applied arts training started in the 1960s with short-term courses offered by the Adult Education Board. Sometime around 1964, the Ministry of Education began planning for a dedicated institute.6 In 1965, Laurence Koh Boon Piang, a Specialist Inspector (Arts and Crafts), was appointed to plan, lead and run the proposed “Queenstown Vocational Institute” (BVI’s original name), overseen by the ministry’s Technical Education Department. He was supported by a team of art teachers, many of whom were sent overseas for applied arts training sponsored by various countries and organisations, including the Colombo Plan.

Wee was one of those sent abroad. He went to Montreal, where he studied under a Canadian team that was constructing displays for the 1967 International and Universal Exposition, or Expo 67, the historic world fair where nations come together to showcase their achievements.

Another Baharuddin teacher, Iskandar Jalil (who later became an eminent ceramist and winner of the Cultural Medallion for Visual Arts in 1988),7 was sent to Maharashtra, India, in 1966 under a Colombo Plan Scholarship to learn textile design. In 1972, he headed to Tajimi, Japan, where he received an education in ceramics engineering, also under the same scholarship. By the time BVI officially opened in 1971, nearly 40 percent of its teaching staff had been trained abroad.8

Master potter Iskandar Jalil using his single-hand technique to create an artwork, 2007. The Cultural Medallion winner taught at the Baharuddin Vocational Institute and later at Temasek Polytechnic’s School of Design until his retirement in 1999. Courtesy of Iskandar Jalil.

Master potter Iskandar Jalil using his single-hand technique to create an artwork, 2007. The Cultural Medallion winner taught at the Baharuddin Vocational Institute and later at Temasek Polytechnic’s School of Design until his retirement in 1999. Courtesy of Iskandar Jalil.

Besides sponsoring the training of staff, several countries also funded the physical set-up of the institute. The British government allocated some $2.25 million from its Special Aid Scheme to construct a new building for the BVI on Stirling Road and furnish it with $850,000 worth of equipment and furniture.9 The Federal Republic of Germany donated some $3.5 million worth of machinery and equipment, provided training fellowships and even sent a team of eight experts here to set up and run a department at BVI to teach students how to work in a commercial press.10

The campus of Baharuddin Vocational Institute on Stirling Road, which opened in 1971. Image reproduced from Baharuddin Vocational Institute. (1971). Singapore: Baharuddin Vocational Institute. (Call no.: RCLOS 372.95957 BVI).

The campus of Baharuddin Vocational Institute on Stirling Road, which opened in 1971. Image reproduced from Baharuddin Vocational Institute. (1971). Singapore: Baharuddin Vocational Institute. (Call no.: RCLOS 372.95957 BVI).

At BVI’s official opening on 8 October 1971, then Minister for Home Affairs Wong Lin Ken acknowledged the international efforts in realising what was ultimately a nationalistic endeavour. “The Baharuddin Vocational Institute is also unique in that it is a multi-national effort,” he said. “In this way, our Republic will some day be able to depend entirely on our own designers and craftsmen in the field of advertising, handicraft souvenir, fashion, woodworking and printing trades.”11

The 1975 cohort of the advertising art class. Seated second from the right is pioneer teacher Wee Chwee Beng, who designed the crest for the institute in 1968. The principal, Rashid Durai, is seated fourth from the right. Courtesy of Collin Choo.

The 1975 cohort of the advertising art class. Seated second from the right is pioneer teacher Wee Chwee Beng, who designed the crest for the institute in 1968. The principal, Rashid Durai, is seated fourth from the right. Courtesy of Collin Choo.

Advertising for BVI

BVI began taking in its first batch of students in 1968, even before the completion of its campus on Stirling Road. Over the next two years, the institute ran courses out of borrowed classrooms at Kim Keat Vocational School, Singapore Vocational Institute, Tanglin Vocational School and even at the printing demonstration room of the East Asiatic Co.12

It cannot be ascertained why the institute was renamed from Queenstown to Baharuddin, but it is most likely in memory of former People’s Action Party assemblyman Baharuddin bin Mohamed Ariff, who passed away in 1961. In 1965, the government had named the new Baharuddin Vocational School in Queensway after him.13 But after the school’s merger with New Town Secondary School in 1969, the name “Baharuddin” was dropped.14 Subsequently, Queenstown Vocational Institute was renamed Baharuddin Vocational Institute.

By the time BVI settled into its new campus on Stirling Road in 1971, some 300 people had already graduated from the institute. In addition, around 800 students were enrolled in 23 fulltime courses, each typically lasting two years.15 The largest intake of over 200 students was in the Handicrafts Department, which offered training in courses ranging from ceramic arts to fabric design and even classes on shellcraft and dollmaking.

However, BVI became best known for its Applied Arts Department, specifically its course in advertising art, now known as graphic design. The two-year programme provided training in the design of advertisements and other forms of visual communication. In 1977, it was reported that the course drew about 200 applicants annually for its 40 vacancies, with interior design coming in a close second.16 Its popularity reflected pent-up demand for the institute’s heavily subsidised courses, with citizens paying a nominal monthly fee of just $6. To apply for the course, candidates had to complete at least Secondary 4, be over 15 years old, pass entrance tests in English, mathematics and science, and sit for an interview to demonstrate their interest in art and design.17

“I knew the [advertising art] course was very competitive by looking at the crowd [that turned up],” recalled former student Patrick Cheah.18 He successfully convinced the assessors with the artwork and posters he had designed in St Joseph’s Institution, and enrolled in 1972.

Not everyone was successful on their first attempt at applying to join at BVI. Nancy Wee, who spent 36 years teaching design – first at BVI and then at Temasek Polytechnic’s School of Design – had applied for the Industrial Technician Certificate in Commercial Art in 1974. “It was really tough. We all had to go for interviews and I didn’t get in on my first try. There were many applicants who were much better than me,” she said. However, she was determined to join BVI. She waited for a year and then re-applied, using the extra time to attend art classes in the hope of boosting her chances. She nailed it on her second attempt. She recalled: “When I went for the interview, I met the same lecturer who had assessed me the first time, so I said, ‘I’m here again!’ He must have felt that this girl was really interested.”19

Having given up a place in pre-university for BVI, Cheah was surprised by the diversity of his fellow classmates. “Sitting next to me was a Hokkien-speaking fellow. I spoke English, and he only spoke Hokkien. But his art was good.” According to Wee Chwee Beng, the early batches of advertising art students ranged from working professionals to those eligible for pre-university as well as academically weaker students. It reflected the flexibility of BVI’s enrolment criteria, which not only considered academic results but also a student’s aptitude for creative work.

Despite the popularity of some of BVI’s courses, the general public often saw the institute’s students as “dropouts” because of its vocational roots. As most Singaporeans aspired for white-collar jobs, opting for vocational institutes was popularly thought of as a last resort for those who struggled academically. “[BVI] wasn’t considered prestigious. Back then, the thinking was that if you went to a vocational school, it was because you were not good at studying. There was this perception that vocational institutes were for dropouts,” said Nancy Wee.20

Such sentiments were reinforced by then Minister for Education Tay Eng Soon in 1984 when he expressed concern that bright students who struggled with English were opting for vocational training and the polytechnics. However, he did single out BVI as an exception because it catered to a specialised interest.21 Nonetheless, parents often contacted Wee Chwee Beng to express concerns for their children’s future. “I even had mothers who [came] to me and [said], ‘I don’t understand why my son wants to study in this vocational institute when he can go to junior college’,” he said.22

Fortunately, he could point to the early success of BVI’s students, who were frequent winners of logo and poster design competitions – even beating professionals in the field. Companies and organisations used such competitions to select and commission the winning designs as their logo. Some examples include the logos for Keppel Shipyard (1968) by Sim Bee Ong and the Singapore Metrication Board (1971) by Lee Chee Kang. The institute also took on work for the government, including the 1974 branding for the Singapore Sports Council as well as designing displays for the temporary maritime museum on Sentosa that same year.

Logos designed by staff and students of Baharuddin Vocational Institute. The abstract designs that distilled letters into shapes were part of a popular international trend known as the modernist graphic design style. Clockwise from top left: Logos for Keppel Shipyard (1968), Singapore Metrication Board (1971), the Vocational Industrial and Training Board (1979) and the Singapore Sports Council (1974).

Logos designed by staff and students of Baharuddin Vocational Institute. The abstract designs that distilled letters into shapes were part of a popular international trend known as the modernist graphic design style. Clockwise from top left: Logos for Keppel Shipyard (1968), Singapore Metrication Board (1971), the Vocational Industrial and Training Board (1979) and the Singapore Sports Council (1974).

Preparing for the Industry

Ensuring that BVI’s students were well equipped to serve the industry was the focus of its curriculum. In the advertising course, students were taught a variety of techniques to manually construct visuals at a time when computers had yet to become part of graphic design production. Besides classes in fundamental skills such as drawing in various media, students were also given hands-on training in modern techniques like photography using a 4X5” large-format camera, typography, layout and packaging design. Such training was supplemented by classes in English, science and mathematics, which were tailored to teach students the theory behind design work.

As a result of their specialised and comprehensive training, BVI students were able to find employment quickly upon graduation, often as in-house designers in advertising agencies and publishing companies. By 1979, BVI’s advertising art course had trained some 371 graduates and these made up a quarter of the advertising art personnel in the industry.23 Many BVI graduates performed well in their jobs and quickly rose through the ranks. Typically, one started out in an advertising agency as a finished artist whose job was to realise the concepts of visualisers and art directors. BVI graduates, however, often leapfrogged this career progression to become art directors.

“The people that advertising agencies could employ before were not trained in design,” said Ronnie Tan who graduated in 1973 and started his own graphic design practice soon after.24 “If you come in knowing how to do typography, drawing images that look good in flat tones… you become an American Idol, one in a million,” he quipped.

Tan believed that the success of BVI graduates was due to a shortage of designers rather than its curriculum. Comparing what he had been taught with his brother’s experience in an advertising agency, he felt that BVI’s teachers, the majority of whom had never worked in the industry, were not attuned to what employers were looking for. Neither did they keep abreast of the latest design trends.

Theresa Yong, the top trainee of the 1977 cohort, felt that the curriculum was too technical-focused. The training at BVI was good enough that Yong could skip a year when she went to study at the Art Center College of Design in California in the United States. However, her overseas experience taught her to push the limits of creative design compared to the more technically driven training she received in Singapore. “The design course [in the US] was challenging in a way that it forced me to open up my mind. It was a different way of training from Singapore,” she said. “The courses themselves were not very different from what we had [at BVI]… it’s how the teachers taught them.”25

Lim Chong Jin of the 1978 cohort, agreed. “The ‘V’ of BVI stood for ‘vocational’. The training was completely skewed towards skill-based competencies. We had to use a 0.2 nib technical pen to draw perfect lines with faultlessly precise spacing,” recalled Lim, who went on to study in the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design in Canada (NSCAD).26

In Canada, Lim found he had to write essays, participate in critical discussions and read art history. “To me, it was more difficult to pursue the course than to get in[to] the school,” he said. “I probably had a strong visual portfolio that supported my acceptance to NSCAD, but the contextual studies and other theoretical aspects were evidently lacking.”

Ahead of Its Time

BVI was aware of its shortcomings and continually reviewed its offerings to ensure it remained relevant and could produce employable graduates. In its early years, BVI even worked with companies to sponsor training which was not included in its curriculum, such as jewellery and rosewood furniture design.27

To better meet the needs of the industry, BVI and other vocational institutes became part of a newly established Industrial Training Board (ITB) in 1973. It led to courses being organised into three levels of certification – Industrial Technician, Trade, and Artisan – to cater for a variety of educational qualifications.

In 1974, BVI’s courses were streamlined and those with poor employment prospects – such as shellcraft and doll and flower making – were phased out. Popular courses were also offered at the Industrial Technician Certificate level and graduates with this certificate were deemed as being on par with the technician-certified students of the polytechnics.28 These courses included advertising art, fashion arts, furniture design and production, interior design and three-dimensional design.

“[The students] will be learning more than studio skills. We want them to know something about costing, production planning, quality control and communications,” explained BVI principal Rashid Durai, who took over from Laurence Koh Boon Piang in 1974. “The idea is to supply the missing link – designers and craftsmen who can fill supervisory and junior management grades,” he added.

In 1977, ITB formalised the ad hoc practice of seeking advice from industry professionals and appointed a Trade Advisory Committee for each institute. BVI’s Applied Arts Trade Advisory Committee was made up of 17 external members from a variety of fields, including advertising, photography, interior design, architecture, handicrafts and sculpture. Reflecting the institute’s most popular offering, the committee was headed by Chan Yen Park, who was then the accounts director of a leading advertising firm as well as President of the Association of Accredited Advertising Agencies.29

The committee conducted a survey of manpower and training needs in the applied arts industry and found an urgent need for more professional designers. In 1980, BVI upgraded its advertising art and interior design courses as three-year diplomas, becoming the first institute in Singapore to offer such a level of training in these fields.30 It helped raise BVI’s profile among the growing number of institutes offering formal design training. In 1988, a new milestone was reached when BVI launched the Diploma in Applied Arts (Product Design) course to support the government’s push for local manufacturers to produce higher-value exports.

Besides responding directly to industry needs, BVI’s Trade Advisory Committee also tried to address other issues that were impacting the quality of design in Singapore. One of the ways suggested by the committee was to raise the level of creativity by getting the institute to look beyond technical education and include art in its curriculum, which was what overseas institutes were doing.

Committee members Khor Ean Ghee and Brother Joseph McNally proposed the establishment of a Singapore Institute of Art and Design. “Good design should be art training, art is a foundation,” said Khor. “If art [is] not good, other design cannot be very good.”31 Unfortunately, the idea was not taken up by the government as it regarded design education to be a domain of industrial training.

In 1990, when Singapore’s education system was restructured, technical education was streamlined and the Normal (Technical) stream was introduced for technically inclined students. BVI’s diploma courses were then transferred to the design school of a new polytechnic – Temasek Polytechnic.

The design school continued operating out of BVI’s premises on Stirling Road until its campus officially opened in Tampines in 1995. At the same time, BVI’s other applied art offerings were absorbed into a new Institute of Technical Education, thereby marking the end of an era for an institute that had, for more than two decades, nurtured and produced some of Singapore’s best design pioneers.

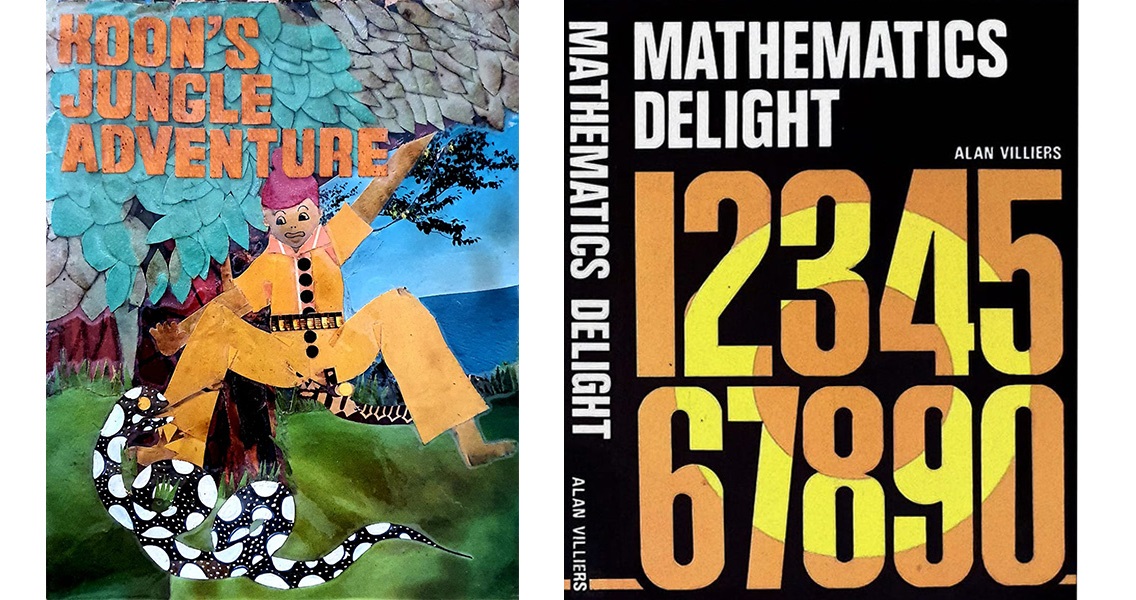

Various book covers designed by former student Collin Choo for his assignments. Courtesy of Collin Choo.

Various book covers designed by former student Collin Choo for his assignments. Courtesy of Collin Choo.

The Cradle of Design

Today, the only physical trace of BVI is a heritage marker outside its former campus on Stirling Road, which was repurposed in 2004 to house the Management Development Institute of Singapore.32

Its more enduring legacy is the generation of practitioners who helped pioneer Singapore’s design industry. Advertising art graduates such as Patrick Cheah, Ronnie Tan and Theresa Yong eventually set up their own practices – DPC Design, Design Objectives and Immortal Design respectively – and were part of the first wave of homegrown graphic design firms in Singapore. Lim Chong Jin rose to become a creative director at local advertising agency TNC Worldwide, before returning to his alma mater in 1992. Today, he is the Director of Temasek Polytechnic’s School of Design.

BVI’s graduates have also made their mark outside Singapore. Fashion stalwart Esther Tay started the fashion label Esta, which grew into a household name in the 1980s and even retailed in Japan. Today, she is better known for designing uniforms for corporations such as DBS, Singtel and NTUC Income. Product design graduates like Low Cheah Hwei currently heads the design team for Philips in Asia, while Nathan Yong has made a name designing furniture for international labels such as Design Within Reach and Ligne Roset.

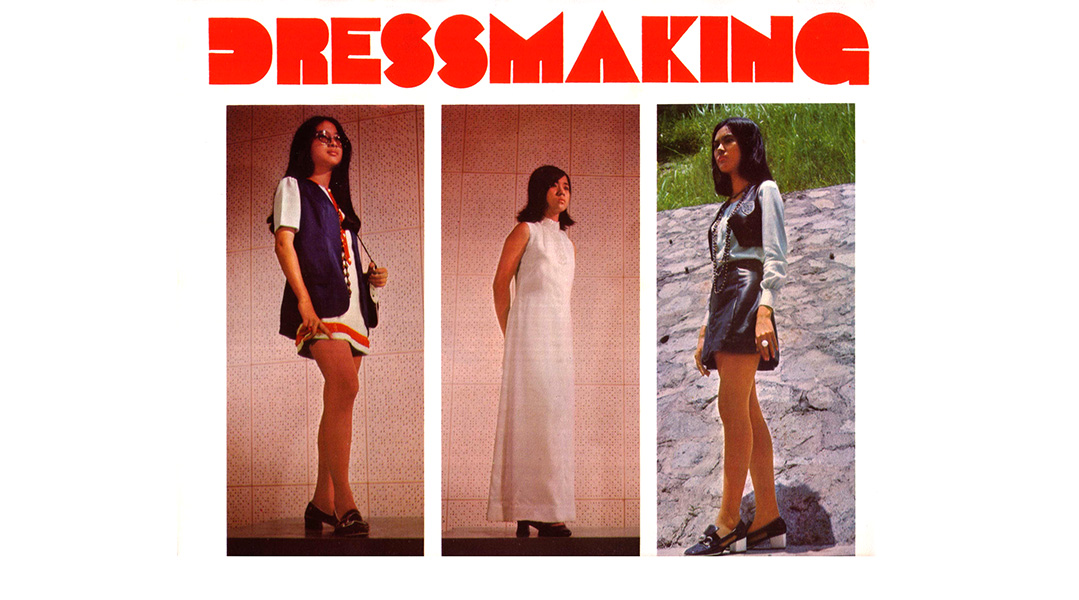

Dressmaking students of Baharuddin Vocational Institute showcasing their designs in the institute’s 1971 commemorative magazine. Image reproduced from Baharuddin Vocational Institute. (1971). Singapore: Baharuddin Vocational Institute. (Call no.: RCLOS 372.95957 BVI).

Dressmaking students of Baharuddin Vocational Institute showcasing their designs in the institute’s 1971 commemorative magazine. Image reproduced from Baharuddin Vocational Institute. (1971). Singapore: Baharuddin Vocational Institute. (Call no.: RCLOS 372.95957 BVI).

By making design education accessible to the man in the street, BVI was instrumental in laying the foundation for Singapore’s design industry. The establishment of a state-sponsored institute to groom and supply a design workforce showed the commitment of the government in developing such services that ultimately spurred the growth of the industry.

Justin Zhuang is a writer and researcher who sees the world through design. He has written about the development of the design industry in Singapore, including Independence: The History of Graphic Design in Singapore Since the 1960s and Fifty Years of Singapore Design.

Justin Zhuang is a writer and researcher who sees the world through design. He has written about the development of the design industry in Singapore, including Independence: The History of Graphic Design in Singapore Since the 1960s and Fifty Years of Singapore Design.

NOTES

-

Personal interview with Wee Chwee Beng, 16 March 2010. ↩

-

The first vocational institute to specialise in craft and trade subjects was the Singapore Vocational Institute set up in 1963 in Balestier. In 1965, the government announced two new institutes, one specialising in engineering in Boon Lay and another for the applied arts in Queenstown. The latter became the Baharuddin Vocational Institute. ↩

-

Ministry of Culture. (1970, November 7). Text of speech by the Minister of State for Education, Dr Lee Chiaw Meng, at the first graduation exercise and open house of Baharuddin Vocational Institute, Stirling Road, on Saturday November 7, at 5 p.m. [Speech]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

Ong, Z.M. (2006). A history of the Nanyang Academy of Fine Arts (1938–1990) [Unpublished thesis]. Singapore: National University of Singapore. (Not available in NLB’s holdings) ↩

-

The Singapore Commercial Art Society. (1977). National commercial art exhibition souvenir catalogue. Singapore: Singapore Commercial Art Society. (Call no.: RSING 741.6 NAT) ↩

-

Ministry of Education. (1964–1969). Proposed Queenstown Vocational Institute for manual and applied arts – training. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

Creamer, R. (2016). Iskandar Jalil. Retrieved from Singapore Infopedia, National Library, Singapore. ↩

-

Ministry of Culture. (1971, October 8). Speech by Prof Wong Lin Ken, Minister for Home Affairs and M.P. for Alexandra, at official opening of the Baharuddin Vocational Institute on Friday, 8th October 1971, at 7.15 p.m. [Speech]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

Kwee, M. (1971, October 1). From doll making to ads display with 70 experts. The Straits Times, p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG; Ministry of Culture, 8 Oct 1971. ↩

-

Baharuddin Vocational Institute Printing School. (1971, October). Singapore: Baharuddin Vocational Institute. (Not available in NLB holdings) ↩

-

Ministry of Culture, 8 Oct 1971. ↩

-

Baharuddin Vocational Institute. (1971). Singapore: Baharuddin Vocational Institute. (Call no.: RCLOS 372.95957 BVI) ↩

-

Lee warns: Be ready for a long dispute with Soek. (1965, June 21). The Straits Times, p. 6. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

New Town Secondary School. (2018). School history. Retrieved from New Town Secondary School website. ↩

-

The Straits Times, 1 Oct 1971, p. 1; Baharuddin Vocational Institute, 1971. ↩

-

Holmberg, J. (1977, July 14). Creativity. New Nation, p. 9. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Notices: Technical Education Department. (1971, March 8). The Straits Times, p. 16. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Personal interview with Patrick Cheah, 1 February 2012. ↩

-

Chew, H.L. (2020). Better by design: Memory of Nancy Wee. Retrieved from Singapore Memory Project website. ↩

-

Chew, 2020, Memory of Nancy Wee. ↩

-

Alfred, H. (1984, April 8). ‘Brain drain’ to poly. The Straits Times, p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Personal interview with Wee Chwee Beng, 16 March 2010. ↩

-

Ministry of Culture. (1979, November 27). Address by Dr Ahmad Mattar, acting Minister for Social Affairs and Chairman, Vocational and Industrial Training Board, at the inaugural meeting of the second term of office of the applied arts trade advisory committee at the VITB Board room [Speech]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

Personal interview with Ronnie Tan, 1 September 2011. ↩

-

Personal interview with Theresa Yong, 1 October 2010. ↩

-

Email interview with Lim Chong Jin, 8 November 2010. ↩

-

Tan, W.J. (1974, June 2). Baharuddin students’ works on sale at exhibition. The Straits Times, p. 10. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The Straits Times, 2 Jun 1974, p. 10. ↩

-

Singapore. Industrial Training Board. (1977, October). ITB appoints its ninth TAC. ITB News, 3. (Call no.: RSING 331.79407105957 ITBSIT) ↩

-

Ministry of Culture, 27 Nov 1979. ↩

-

He, S. (2008, September 4). Oral history interview with Khor Ean Ghee [许延义] [MP3 recording no. 003343/12/08]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

Management Development Institute of Singapore. (2020). MDIS Heritage 2000. Retrieved from MDIS website. ↩