Of Parks, Trees and Gardens: The Greening of Singapore

Lim Tin Seng traces the journey from the first botanical garden in 1822 to the “City in Nature” vision in 2020.

A panoramic shot of East Coast Park taken in 2016, one of Singapore’s biggest parks. It was built in the 1970s on reclaimed land. Photo by Chensiyuan. Retrieved from Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 4.0).

A panoramic shot of East Coast Park taken in 2016, one of Singapore’s biggest parks. It was built in the 1970s on reclaimed land. Photo by Chensiyuan. Retrieved from Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 4.0).

Singapore is justly known for its tree-lined streets, its colourful roadside flowers and the abundance of parks in the city centre and in housing estates. The current greening efforts can be traced to 1967 when then Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew introduced the “Garden City” vision. Over time, that vision evolved from “Garden City” to “City in a Garden” and the current “City in Nature”, which is part of the larger environmental sustainability Singapore Green Plan 2030.1

While the “Garden City” vision only dates back five decades, the practice of creating gardens and parks as well as the planting of trees in the city is something that goes back some 200 years.

The First Garden on Government Hill

Just a few years after Stamford Raffles landed on Singapore’s shores in 1819, the British took steps to set up a botanic garden. The garden was the brainchild of Raffles and the Danish surgeon and naturalist Nathaniel Wallich, who had previously been Superintendent of the Royal Gardens in Calcutta, India.

Raffles allocated a “most advantageous site”, as he put it, on Government Hill (now Fort Canning Hill), for the new garden. According to Wallich, the garden was set up for the “experimental cultivation of the indigenous plants of Singapore”. This effort followed the long-established British tradition of setting up botanic gardens in its colonies to experiment with growing commercially valuable crops and for the study of native plants.2

Within a year of its establishment in 1822, the botanic garden in Singapore had grown to occupy the 19 hectares of land that Raffles had allocated, cultivating crops such as nutmeg, cocoa and cloves. However, the garden – under the supervision of Scottish surgeon William Montgomerie – was shut down in 1829 because of its high cost of upkeep, coupled with a lack of funding and government support, particularly after Raffles’ permanent departure from Singapore in June 1823.3

In 1836, another botanic garden was created on a much smaller plot on Fort Canning. Led by the Singapore Agricultural and Horticultural Society, where Montgomerie was vice-president, the 2.8-hectare garden was primarily used to grow nutmeg. A decade later, however, this garden was also abandoned after the price of nutmeg declined.4

The Singapore Botanic Gardens

About two decades later, in 1859, the Agricultural and Horticultural Society set up a landscaped ornamental and leisure garden on a 23-hectare tract in Tanglin. This took root and eventually became the Singapore Botanic Gardens (SBG). In 2015, it was declared a UNESCO (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization) World Heritage Site.

Its first superintendent, Lawrence Niven, organised flower shows and horticultural fairs in the gardens to attract more visitors. He also added many features such as the Swan Lake, Bandstand Hill and the interconnecting curving pathways.5

After the Straits Settlements government took over the management of the gardens in 1874, it continued to grow under the stewardship of directors such as Henry James Murton (1875–80), Nathaniel Cantley (1880–88) and Henry Nicholas Ridley (1888–1912).

Murton expanded the gardens with a 41-hectare northern extension in 1879. He also established the Economic Garden the same year for the research and conservation of plants with economic potential, such as coffee, sugarcane and pará rubber. In addition, Murton set up a zoo within the gardens’ compound, which at its peak between 1875 and 1878, housed around 150 animals, including leopards and a tiger.6

Cantley established nurseries and launched a tree-planting programme to reforest parts of the land that had previously been cleared by plantation owners (Cantley had authored an 1883 report on deforestation that led to the demarcation of Singapore’s first forest reserves and the creation of a Forest Department). For the tree planting programme, he picked trees like teak, American rain tree and mahogany for their ability to produce quality timber to support construction work and other commercial activities such as furniture making.7 It should be mentioned that Cantley was more concerned about safeguarding Singapore’s timber supply rather than environmental protection and conservation.8

Ridley continued efforts to reforest the reserves. By the time the Forest Department was transferred to the Collector of Land Revenue in 1895, the amount of land designated as forest reserves (forest land set aside for timber reserves) had increased from 8,000 acres in 1884 to nearly 12,000 acres.9 Ridley also helped develop the botanical and horticultural research arm of the gardens by turning it into a centre for rubber distribution and enlarging its herbarium collection with plants that he had gathered from his expeditions around the island. One of his most important additions to the gardens was the orchid hybrid known as Vanda Miss Joaquim, later designated as Singapore’s national flower in 1981.10 The orchid had been cultivated by Agnes Joaquim, who crossed the Vanda hookeriana with the Vanda teres to produce the orchid that Ridley subsequently named Vanda Miss Joaquim.11

Another influential director of the Botanic Gardens was Richard Eric Holttum (1925–42, 1946–49). Holttum started the orchid-breeding programme and also managed to get the control of the forest reserves returned to the Botanic Gardens. However, after the handover in 1939, there were only three remaining reserves – Bukit Timah, Kranji and Pandan.12

Roadside Trees, Parks and Recreational Spaces

The Botanic Gardens also worked with the Singapore Municipality (succeeded by the Singapore Municipal Commission in 1887) to plant roadside trees in the 1860s. Some of the trees planted include the cotton tree, angsana tree, flame of the forest and rain tree. These were planted along major thoroughfares such as Orchard Road, Scotts Road, Anderson Road, Jalan Besar and Balestier Road.13

The Municipal Commission was also responsible for the upkeep and planning of recreational spaces for the public. Prior to the 1920s, there were only a handful of such spaces like the Padang, the sea-front garden at Connaught Drive (today’s Esplanade Park), Dhoby Green (a grassy strip near Dhoby Ghaut), People’s Park, Finlayson Green and the area around Dalhousie Obelisk.14

Private individuals also created notable gardens. Whampoa Gardens, owned by prominent Chinese businessman and community leader Hoo Ah Kay (better known as Whampoa), was located on the grounds of his lavish mansion on Serangoon Road. The garden was described as beautifully landscaped and contained many exotic tropical flowers and plants. It was opened to the public during the Lunar New Year.

A garden pavilion in Whampoa Gardens on Serangoon Road, mid-19th century. The garden was owned by Chinese businessman and community leader Hoo Ah Kay (also known as Whampoa), and was a beautifully landscaped garden with many exotic tropical flowers and plants. Courtesy of the National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board.

A garden pavilion in Whampoa Gardens on Serangoon Road, mid-19th century. The garden was owned by Chinese businessman and community leader Hoo Ah Kay (also known as Whampoa), and was a beautifully landscaped garden with many exotic tropical flowers and plants. Courtesy of the National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board.

Another private garden was the Alkaff Lake Gardens off MacPherson Road, which was opened to the public in 1929. Owned by the wealthy Arab merchant Syed Shaik Alkaff, it was a Japanese-style garden that had a lake for rowing boats, neatly landscaped paths and tea houses.15

Following the release of the 1918 Housing Commission report, which called for the creation of more recreational spaces for residents who were otherwise largely confined to their “dark airless houses”, the Municipal Commission began to create more parks, starting with Katong Park, which was completed in 1927.16 In the 1930s, the commission also built Farrer Park and King George V Park in Fort Canning.17

After the Japanese Occupation (1942–45), the Municipal Commission, which was renamed City Council in 1951, continued to increase green recreational spaces and enhance existing parks. Between 1955 and 1961, the City Council added more amenities and landscaping to King George V Park, Katong Park and Esplanade Park.18

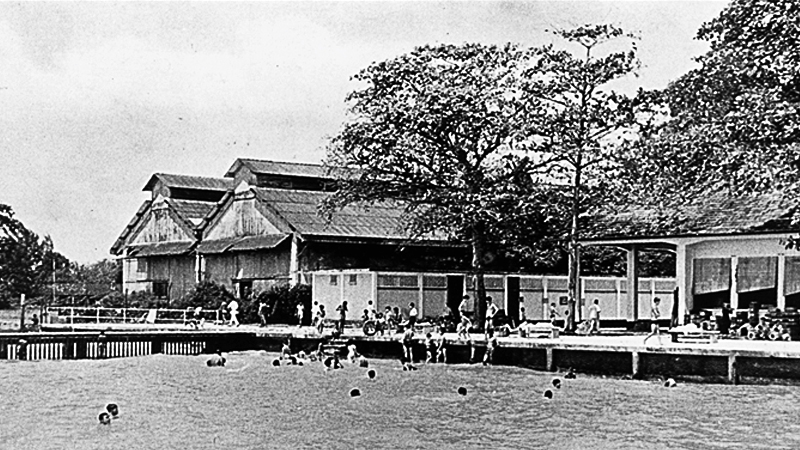

Katong Park, c. 1950s. Completed in 1927, the park had landscaped footpaths, playgrounds, a bandstand and even a swimming enclosure extending about 30 m into the sea. Tan Kok Kheng Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Katong Park, c. 1950s. Completed in 1927, the park had landscaped footpaths, playgrounds, a bandstand and even a swimming enclosure extending about 30 m into the sea. Tan Kok Kheng Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Creating a Garden City

Despite these efforts, the city area was mostly a concrete jungle. Singapore’s first Master Plan, released in 1958, sought to address this problem by almost quadrupling the land set aside for recreation from 274 hectares in 1953 to 1,050 hectares by 1972. These were to be located along the coasts of Bedok, Changi and Pasir Ris as well as the fringes of the built-up central area.19

In 1959, the newly elected government formed by the People’s Action Party embarked on efforts to beautify Singapore. Between 1959 and 1966, several new green spaces such as the Duxton Plain Parkway, Crawford Park, Model Traffic Playground, Mount Faber Scenic Park and the garden above Raffles Square underground carpark were built.20 The government also launched a tree planting campaign in 1963. However, Singapore would not have an official greening policy until the “Garden City” vision articulated by then Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew in 1967.21

As Lee noted at the announcement of the “Garden City” vision, there were many advantages to adding more greenery to the country: “[A]part from making life more pleasant, you give Singapore a very good reputation, then people come, they stay. Wherever you want to go in the region, you can use this place as a base. Your hotel trade will boom and hotels create employment and you help solve your unemployment problem.”22

The plan was carried out in two phases. The first saw the large-scale planting of roadside trees and shrubs by the Parks and Trees Unit of the Public Works Department, which became the Parks and Recreation Department (PRD) in 1975. The trees included species that could grow fast and endowed with shady crowns, such as the angsana tree, rain tree, flame of the forest and the frangipani. Shrubs like the bougainvillea, the red Ixora, the bamboo orchid and the Cassandra were also grown.23 By 1970, over 55,000 new trees had been planted, increasing to some 158,600 in 1974 and 1.4 million by June 2014.

Today, tree planting efforts are headed by the National Parks Board (NParks), which was formed in 1990 to manage Singapore’s national parks. It was expanded in 1996 to incorporate the roles of the PRD, including planting roadside trees and developing recreational spaces and parks.24

Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew watering the jambu laut sapling that he had just planted in Tanjong Berlayar, 1975. Tree Planting Day was made an annual event in 1971. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew watering the jambu laut sapling that he had just planted in Tanjong Berlayar, 1975. Tree Planting Day was made an annual event in 1971. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

The second phase of the “Garden City” plan, from the mid-1970s onwards, involved the creation of parks throughout the island. These new parks were larger and equipped with a wide range of facilities to meet the diverse recreational needs of different population groups.

The largest of such parks are known as regional parks and they range from 10 hectares to 200 hectares. These parks include East Coast Park, Mount Faber Park, and MacRitchie Reservoir Park.25 Then there are the community parks like Toa Payoh Town Park, Bishan-Ang Mo Kio Park and Yishun Neighbourhood Park located near housing estates. Ranging from 1,000 sq m to 40 hectares, these parks are aimed at residents living in the vicinity.26 In the city area, there is another type of park ranging from 1,000 sq m to 30 hectares in size. Parks such as the Merlion Park and the Fort Canning Historic Park beautify the cityscape and function as “green lungs” for the built-up city environment.27

An aerial view of Bishan-Ang Mo Kio Park, one of the largest urban parks in central Singapore, with Bishan housing estate in the background. The park, which is popular with residents living nearby, has a naturalised 3-kilometre meandering river, lush greenery, a wide variety of flora and fauna, and pond gardens and river plains. Courtesy of the Singapore Tourism Board.

An aerial view of Bishan-Ang Mo Kio Park, one of the largest urban parks in central Singapore, with Bishan housing estate in the background. The park, which is popular with residents living nearby, has a naturalised 3-kilometre meandering river, lush greenery, a wide variety of flora and fauna, and pond gardens and river plains. Courtesy of the Singapore Tourism Board.

The efforts to plant roadside trees and build parks were supplemented by laws to protect the greenery. In 1971, the Trees and Plants Act was enacted to protect existing and newly planted trees. The legislation was expanded in 1975 to mandate that developers had to set aside green spaces around buildings, roads and open-air car parks. Today, the laws that protect nature include the Parks and Trees Act (2005), the Animals and Birds Act (2002), and the Wildlife Act (2000). These are administered by NParks.28

Up Close and Personal with Nature

From the 1990s, the “Garden City” vision went beyond planting trees and building parks to include ways to bring the community closer to nature. This shift was sketched out in the 1991 Concept Plan by the Urban Redevelopment Authority (URA) which aimed to transform Singapore into an island city where nature, waterbodies and urban development are woven seamlessly together.

One of the first initiatives taken by NParks was the introduction of the Park Connector Network (PCN) in 1991. These are green corridors that allow park users to walk, skate, jog, or cycle from one park or nature site to another for leisure.29 The first park connector, completed in 1992, was the 7-kilometre stretch linking Bishan-Ang Mo Kio Park to Kallang Riverside Park. Today, there are around 70 park connectors in Singapore stretching over 340 km, and this is set to increase to 500 km by 2030.

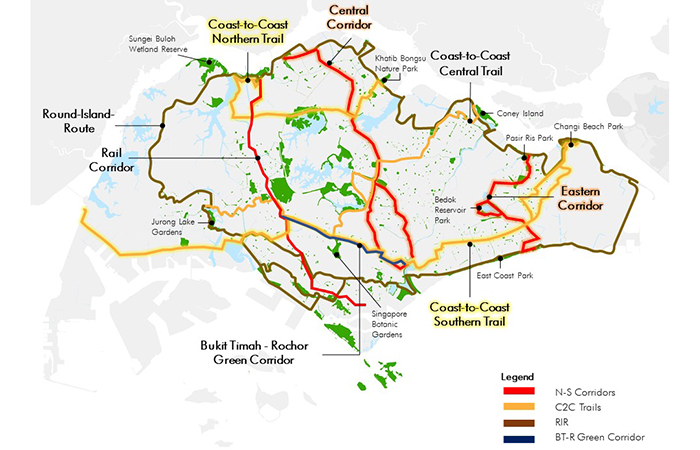

Singapore boasts a large interlinking network of park connectors comprising the Round-Island-Route, Central Corridor, Eastern Corridor, Rail Corridor and the coast-to-coast trails. Courtesy of NParks.

Singapore boasts a large interlinking network of park connectors comprising the Round-Island-Route, Central Corridor, Eastern Corridor, Rail Corridor and the coast-to-coast trails. Courtesy of NParks.

Many of the existing park connectors also link to water canals, rivers and reservoirs that have been transformed under the Active, Beautiful and Clean (ABC) Waters Programme introduced by the Public Utilities Board in 2006. The programme aims to create beautiful and clean streams, rivers and lakes with picturesque community spaces for all to enjoy.30 As Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong noted when he launched the programme: “By linking up our water bodies and waterways, we will create new community spaces that are clean, pleasant, and bustling with life and activities.”31

A prime example is the transformation of a stretch of the Kallang River that was once a concrete canal by the edge of the Bishan-Ang Mo Kio Park into a naturalised and meandering river in 2012. The river is now home to different species of water birds and dragonflies.32

The 1991 Concept Plan also pledged to safeguard Singapore’s natural environment by conserving 3,000 hectares of nature sites. Comprising wooded areas, bird sanctuaries, mangrove swamps, waterbodies and nature reserves, these 19 nature sites were identified after the release of Singapore’s first environmental blueprint – the Singapore Green Plan – in 1992.33

Today, Singapore has 24 nature sites, including four nature reserves – Bukit Timah Nature Reserve, Central Catchment Nature Reserve, Sungei Buloh Wetland Reserve and Labrador Nature Reserve – as well as 20 nature areas found throughout the main island and also on the offshore islands of Pulau Tekong, Pulau Ubin and Sisters’ Islands. These nature sites are conserved under the Parks and Trees Act.

The boardwalk at the Sungei Buloh Wetland Reserve. The reserve opened as a nature park in 1993, was gazetted as a nature reserve in 2002 and became Singapore’s first ASEAN Heritage Park the following year. It is home to some of the world’s rarest mangroves and is a stopover point for migratory birds escaping the northern winter on their way to Australia. Courtesy of the Singapore Tourism Board.

The boardwalk at the Sungei Buloh Wetland Reserve. The reserve opened as a nature park in 1993, was gazetted as a nature reserve in 2002 and became Singapore’s first ASEAN Heritage Park the following year. It is home to some of the world’s rarest mangroves and is a stopover point for migratory birds escaping the northern winter on their way to Australia. Courtesy of the Singapore Tourism Board.

By 2030, Singapore aims to create more of such spaces, including a 40-hectare nature park in Khatib Bongsu, which is a rich mangrove and mudflat habitat on the north-eastern coast of Singapore, the 8.9-hectare Bukit Batok Hillside Nature Park and the 16-hectare Bukit Batok Central Nature Park.34

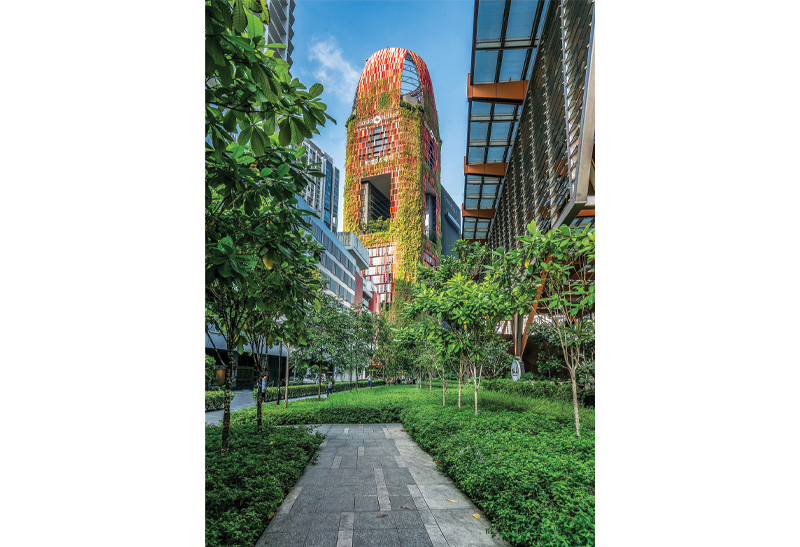

In the city area, the URA has been promoting high-rise greenery through the Landscaping for Urban Spaces and High-Rises (LUSH) programme, which incentivises developers to introduce greenery into their projects. Some of these options include landscaping within the building and creating sky terraces.35 Today, over 550 commercial developments and more than two-thirds of all new residential projects have joined LUSH. These buildings include Oasia Hotel Downtown in the city-centre and JEM shopping mall in Jurong East.

The Oasia Hotel Downtown with lush foliage on its facade, 2019. In 2009, the Urban Redevelopment Authority introduced the Landscaping for Urban Spaces and High-Rises (LUSH) programme to integrate greenery and biodiversity into the facade of buildings. Photo by 100pss. Retrieved from Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 4.0).

The Oasia Hotel Downtown with lush foliage on its facade, 2019. In 2009, the Urban Redevelopment Authority introduced the Landscaping for Urban Spaces and High-Rises (LUSH) programme to integrate greenery and biodiversity into the facade of buildings. Photo by 100pss. Retrieved from Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 4.0).

Becoming a City in a Garden

Singapore’s “Garden City” vision eventually evolved into the “City in a Garden” concept, which was introduced in 2011. This vision was about “connecting our communities and our places and spaces through parks, gardens, streetscapes and skyrise greenery… bring[ing] the green spaces and the biodiversity closer to our homes and workplaces,” said Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong. “[W]e are determined that our people should be… in touch with nature, to be never far from green spaces and blue waters, where they can relax, recharge, where they can let their children and pets run around safely, and where they can take glamorous wedding pictures.”36

The commitment to green Singapore can be seen in the creation of Gardens by the Bay on a prime site in Marina Bay. Comprising three public gardens – Bay South, Bay East and Bay Central – and occupying 101 hectares in total, Gardens by the Bay was conceptualised in 2005 and completed in 2012 as a new public green space in the city area. With its two futuristic, cavernous glass domes and 18 gigantic concrete-and-steel vertical gardens called Supertrees, Gardens by the Bay represents the realisation of the “Garden City” vision and its transition into “City in a Garden”.

The Supertree Grove at Gardens by the Bay, 2012. Ranging from 25 m to 50 m tall, some of these structures act as vertical gardens and are able to harvest rainwater and solar energy. Courtesy of Gardens by the Bay.

The Supertree Grove at Gardens by the Bay, 2012. Ranging from 25 m to 50 m tall, some of these structures act as vertical gardens and are able to harvest rainwater and solar energy. Courtesy of Gardens by the Bay.

The practice of integrating greenery into the built environment was applied to public housing estates via the Biophilic Town Framework. Developed in 2013 by the Housing & Development Board (HDB), the framework aims to create nature-centric public housing estates with ample greenery to reduce heat and noise, and to allow for community farming and the appreciation of nature. Previously, greenery was incorporated into the HDB living environment only through the provision of green spaces for mostly recreational activities. The biophilic framework was piloted in Punggol Northshore District in 2015 and then adopted in the planning and design of Bidadari’s Woodleigh neighbourhood in 2016. In 2018, it was announced that the framework would be rolled out to all newly launched housing projects.37

City in Nature and the Singapore Green Plan

In 2020, a new vision for greening Singapore was announced. “We want to transform Singapore into a City in Nature to provide Singaporeans with a better quality of life, while co-existing with flora and fauna on this island,” said then Second Minister for National Development Desmond Lee.38

This would be achieved by having even more nature parks, enhancing the natural environment in new and existing parks and gardens, integrating nature into the built environment and making green spaces even more accessible. By 2030, it is envisioned that Singapore would have another 200 hectares of nature parks, up to 200 hectares of skyrise greenery, one million more trees planted, up to 500 km of park connectors created, and all households would be a 10-minute walk from a park.39

The “City in Nature” strategy is also one of the key pillars in the Singapore Green Plan 2030. Launched in February 2021, the Green Plan is the country’s latest 10-year blueprint to advance the national agenda of sustainable development amid the challenges of climate change.

The evolution from “Garden City” to “City in a Garden” to “City in Nature” shows how greening the country has become a major priority over the decades. The government moved from just planting trees to setting up parks, expanding these green areas and thinking of nature in the larger context of both landscaped gardens and natural habitats.

The latest Singapore Green Plan takes it one step further by merging the trend towards more greenery with the need for sustainability in the face of the challenges arising from climate change. If the plan succeeds, residents in Singapore will be able to enjoy a considerably greener environment, and the country itself will be closer to realising its vision for sustainable development.

Lim Tin Seng is a Librarian with the National Library, Singapore. He is the co-editor of Roots: Tracing Family Histories – A Resource Guide (2013), Harmony and Development: ASEAN-China Relations (2009) and China’s New Social Policy: Initiatives for a Harmonious Society (2010). He writes regularly for BiblioAsia.

Lim Tin Seng is a Librarian with the National Library, Singapore. He is the co-editor of Roots: Tracing Family Histories – A Resource Guide (2013), Harmony and Development: ASEAN-China Relations (2009) and China’s New Social Policy: Initiatives for a Harmonious Society (2010). He writes regularly for BiblioAsia.

NOTES

-

Prime Minister’s Office. (2011, August 14). National Day Rally 2011. Retrieved from Prime Minister’s Office website; Ministry of National Development. (2020, March 4). Speech by 2M Desmond Lee at the Committee of Supply Debate 2020 – Transforming Singapore into a City of Nature. Retrieved from Ministry of National Development website; Tan, A. (2021, February 10). Singapore Green Plan 2030 to change the way people live, work, study and play. The Straits Times. Retrieved from The Straits Times website. ↩

-

Tinsley, B. (2009). Gardens of perpetual summer: The Singapore Botanic Gardens (p. 22). Singapore: National Parks Board. (Call no.: RSING 580.735957 TIN); Corlett, R.T. (July 1992). The ecological transformation of Singapore, 1819–1990. Journal of Biogeography, 19 (4), 411–420, pp. 411–412; Hanitsch, R. (1913, December). Letters of Nathaniel Wallich relating to the establishment of Botanical Gardens in Singapore. Journal of the Straits Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, (65), 39–48, p. 45. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website; Bastin, J. (1981). The letters of Sir Stamford Raffles to Nathaniel Wallich 1819–1824. Journal of the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, 54 (2), 1–73, p. 13. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website. ↩

-

Tinsley, 2009, p. 27; Taylor, N.P. (2014). Environmental relevance of the Singapore Botanic Gardens (pp. 115–116). In T.P. Barnard (Ed.), Nature contained: Environmental histories of Singapore (pp. 115–137). Singapore: NUS Press. (Call no.: RSING 304.2095957 NAT) ↩

-

Singapore. (1836, May 28). Singapore Chronicle and Commercial Register, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG; Taylor, 2014, p. 116. ↩

-

Zaccheus, M. (2015, July 4). Singapore Botanic Gardens clinches prestigious Unesco World Heritage site status. The Straits Times. Retrieved from Factiva via NLB’s eResources website; [Untitled]. (1859, December 24). The Straits Times, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG; Purseglove, J.W. (1959). History and functions of Botanic Gardens with special reference to Singapore. The Gardens’ Bulletin, 17 (2), 130. (Call no.: RCLOS 580.744 SIN); Tinsley, 2009, p. 28; Taylor, 2014, pp. 117–118. ↩

-

Tinsley, 2009, pp. 32–34; The botanical gardens. (1876, November 11). The Straits Times, p. 4. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Cantley, N. (1883). Report on the forests of the Straits Settlements. In Proceedings of the Legislative Council of the Straits Settlements for the year 1883 (p. 491). Singapore: Government Printing Office. (Call no.: RRARE 328.5957 SSLCPL; Accession no.: B20048240I); Cantley, N. (1885). Annual report on the Forest Department, Straits Settlements, for the year 1884. In Proceedings of the Legislative Council of the Straits Settlements for the year 1885 (pp. C229–C231). Singapore: Government Printing Office. (Call no.: RRARE 328.5957 SSLCPL; Microfilm no.: NL30534) ↩

-

Lum, S., & Sharp, I. (Eds.). (1996). A view from the summit: The story of Bukit Timah Nature Reserve (pp. 20–21). Singapore: Nanyang Technological University and the National University of Singapore. (Call no.: RSING 333.78095957 VIE) ↩

-

Davidson, G.W.H., & Chew, P.T. (2019, May 25). Historical review of Bukit Timah Nature Reserve, Singapore. Gardens’ Bulletin Singapore, 71 (Supplement 1), 19–40, p. 23. Retrieved from Singapore Botanic Gardens website. ↩

-

Tinsley, 2009, pp. 39–46; Hassan Ibrahim & Lee, S. (2005, July). The day the rubber trees cried. Gardenwise, 25, 25. Retrieved from Singapore Botanic Gardens website. ↩

-

Wright, N., Locke, L., & Johnson, H. (2018, Apr–Jun). Blooming lies: The Vanda Miss Joaquim story. BiblioAsia, 14 (1), 2–9, p. 3. Retrieved from BiblioAsia website. ↩

-

Tinsley, 2009, pp. 48–60; Lum & Sharp, 1996, pp. 22–25. ↩

-

Lim, T.S. (2018, December). The greening of Singapore: Parks and roadside trees from colonial rule to the present. Journal of the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, 91 (2), 79–101, pp. 80–82. Retrieved from Project Muse website. ↩

-

Lim, Dec 2018, p. 84. ↩

-

Kwa, C.G., & Ke, M. (Eds.). (2019). A general history of the Chinese in Singapore (p. 878). Singapore: Singapore Federation of Chinese Clan Associations, World Scientific. (Call no.: RSING 305.895105957 GEN); Uma Devi, G., et al. (2002). Singapore’s 100 historic places (p. 118). Singapore: Archipelago Press; National Heritage Board. (Call no.: RSING 959.57 SIN); Tyers, R.K. (1993). Ray Tyers’ Singapore: Then & now (p. 199). Singapore: Landmark Books. (Call no.: RSING 959.57 TYE); Ferroa, R. (1948, April 20). S’pore’s forgotten park. The Singapore Free Press, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Lim, Dec 2018, pp. 84–86. ↩

-

Farrer Park now completed. (1936, March 6). Morning Tribune, p. 11; Almost completed. (1938, December 8). The Malaya Tribune, p. 20. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Lim, Dec 2018, p. 88. ↩

-

Singapore. (1955). Master plan: Written statement (pp. 6, 8–9, 11, 20). Singapore: Government Printing Office. (Call no.: RCLOS 711.4095957 SIN) ↩

-

Lim, Dec 2018, p. 89; ‘Plant a tree’ drive in S’pore. (1963, June 12). The Straits Times, p. 9. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

S’pore to become beautiful, clean city within three years. (1967, May 12). The Straits Times, p. 4. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Ministry of Communications and Information. (1967, May 11). The future of Singapore depends heavily upon its cleanliness [Speech]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

Public Works Department. (1973). Annual report 1972 (p. 51). Singapore: Government Printing Office. (Call no.: RCLOS 354.59570086 SIN); Auger, T. (2013). Living in a garden: The greening of Singapore (pp. 26, 34–37). Singapore: Editions Didier Millet. (Call no.: RSING 363.68095957 AUG) ↩

-

National Parks Board. (2020). About the movement. Retrieved from National Parks Board website; National Parks Board. (2021, March 1). Mission and history. Retrieved from National Parks Board website. ↩

-

Lee, S.K., & Chua, S.E. (1992). More than a garden city (p. 19). Singapore: Parks & Recreation Department, Ministry of National Development. (Call no.: RSING 333.783095957 LEE) ↩

-

Lee & Chua, 1992, p. 78. ↩

-

Lee & Chua, 1992, p. 64. ↩

-

National Parks Board. (2020, May 29). Laws administered by NParks. Retrieved from National Parks Board website website. ↩

-

Urban Redevelopment Authority. (1991). Living the next lap: Towards a tropical city of excellence (pp. 4–7, 28–31). Singapore: Urban Redevelopment Authority. (Call no.: RSING 307.36095957 LIV); Ministry of Information and the Arts. (1992, August 14). Speech by S Dhanabalan, Minister for National Development at the opening of the Park Network System, Kallang River Phase I on Friday 14 Aug 92 at 5.00 pm at Kallang River Park Connector (Bishan Road) [Speech]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

National Parks Board. (n.d.). North Eastern Riverine Loop [Brochure]. Retrieved from National Parks Board website; National Parks Board. (2012, April). Western Adventure Loop [Brochure]. Retrieved from National Parks Board website; Urban Redevelopment Authority. (2021, January 11). More greenery & play spaces. Retrieved from Urban Redevelopment Authority website; National Parks Board. (2018). A natural connection: Annual report 2016/2017 (p. 57). Retrieved from National Parks Board website; Heng, M. (2020, March 5). S’pore’s 2030 goal: More gardens, park connectors. The Straits Times. Retrieved from The Straits Times website. ↩

-

Ministry of Information, Communications and the Arts. (2007, February 6). Speech by Mr Lee Hsien Loong, Prime Minister, at the Active, Beautiful and Clean (ABC) Waters Exhibition, 6 February 2007, 10:00am at the Asian Civilisations Museum. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

Khoo, T.C., & Chew, V. (Eds.). (2017). The Active, Beautiful, Clean Waters Programme: Water as an environmental asset (pp. xvii, 3, 35, 49, 57, 61). Singapore: Singapore Centre for Liveable Cities. (Call no.: RSING 333.7845095957 ACT); National Parks Board. (2012, February 15). Natural river through Bishan Park. Retrieved from National Parks Board website. ↩

-

Urban Redevelopment Authority, 1991, p. 31; Moiz, A. (1993). The Singapore Green Plan: Action programmes (p. 51). Singapore: Times Editions Pte Ltd. (Call no.: RSING 363.7095957 SIN) ↩

-

National Parks Board. (2019, May 20). Conserving our biodiversity: Singapore National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan (pp. 2, 16). Retrieved from National Parks Board website; The Straits Times, 5 Mar 2020; Ng, K.G. (2020, December 7). Two new parks in Bukit Batok to be part of nature corridor connecting Central Catchment and Tengah. The Straits Times. Retrieved from The Straits Times website. ↩

-

Green on the rise. (2019). Skyline, (11), 26–29. Retrieved from Urban Redevelopment Authority website; Ng, J.S., & Charles, R.N. (2017, November 9). More green spaces in high-rise buildings targeted for Singapore’s concrete jungle. The Straits Times. Retrieved from The Straits Times website. ↩

-

Prime Minister’s Office. (2012, June 28). Speech by Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong at the opening of Gardens by the Bay. Retrieved from Prime Minister’s Office website. ↩

-

Housing & Development Board. (2018, July 18). Homes at one with nature. Retrieved from Housing & Development Board website; Wong, W. (2018, July 18). All new HDB projects to feature nature-centric designs. CNA. Retrieved from CNA website. ↩

-

Ministry of National Development, 4 Mar 2020. ↩

-

Ministry of National Development, 4 Mar 2020. ↩