Singapore’s Environmental Histories

Georgina Wong explores the relationship between the human and natural worlds, and shares highlights from the National Library’s latest exhibition.

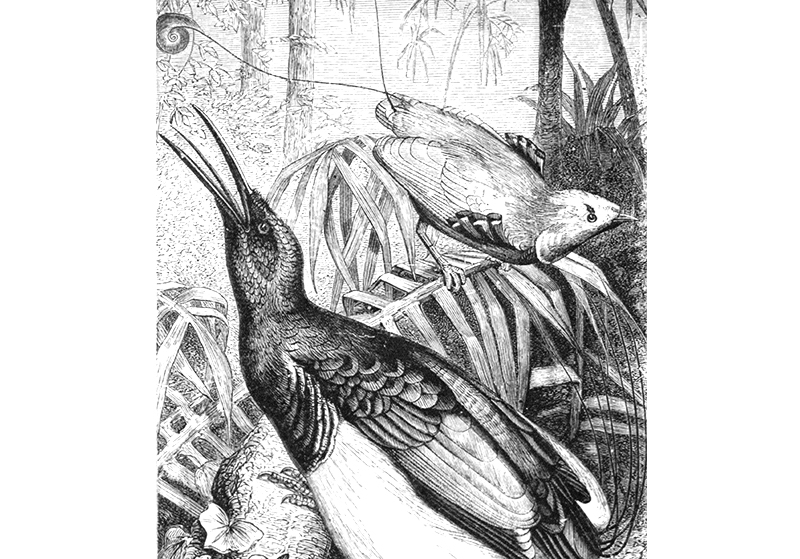

Famed naturalist Alfred Russel Wallace spent eight years, from 1854 to 1862, exploring present Malaysia, Singapore and Indonesia, collecting and recording more than 125,000 species of wildlife. Shown here are illustrations of the king bird-of-paradise and the twelve-wired bird-of-paradise. Image reproduced from Wallace, A.R. (1874). The Malay Archipelago: The Land of the Orang-utan, and the Bird of Paradise; a Narrative of Travel, with Studies of Man and Nature (between pp. 548 and 549). London: Macmillan. Retrieved from BookSG. Collection of the National Library, Singapore. (Call no.: RRARE 915.9804 WAL; Accession no.: B18835319E).

Famed naturalist Alfred Russel Wallace spent eight years, from 1854 to 1862, exploring present Malaysia, Singapore and Indonesia, collecting and recording more than 125,000 species of wildlife. Shown here are illustrations of the king bird-of-paradise and the twelve-wired bird-of-paradise. Image reproduced from Wallace, A.R. (1874). The Malay Archipelago: The Land of the Orang-utan, and the Bird of Paradise; a Narrative of Travel, with Studies of Man and Nature (between pp. 548 and 549). London: Macmillan. Retrieved from BookSG. Collection of the National Library, Singapore. (Call no.: RRARE 915.9804 WAL; Accession no.: B18835319E).

“[I]t is apparent that but few years can elapse before the whole island will be denuded of its indigenous vegetation, when its climate will no doubt be materially altered (probably for the worse), and countless tribes of interesting insects become extinct. I am therefore working hard at the insects alone for the present, and will give you some little notion of what I have done and may hope to do.”1

The National Library’s latest exhibition, “Human x Nature: Environmental Histories of Singapore”, explores the history of human relationships with nature on the island over the last 200 years. These relationships – be they scientific study, sustenance farming or commercial exploitation – vary between communities and have evolved over time. As much of the ways in which humans interact with the environment are based on our understanding and perception of the natural world, the exhibition begins with an examination of the study of natural history in Southeast Asia.

The Study of Nature

While the region has long been the subject of much fascination for travellers and explorers, especially for Europeans since the 16th century, the influx of naturalists and scientists to the region only started in the 17th century and intensified throughout the 18th century when the British and Dutch East India companies began their commercial and colonial efforts in earnest. A thorough understanding of the environment was considered a key component of colonial expansion as it enabled European empires to seize control of merchant economies, which relied heavily on the trade of natural resources such as spices, timber and plantation crops.

To this end, the British East India Company (EIC) – the commercial and colonial arm of the British government – and later the Colonial Office, actively encouraged and funded their employees’ efforts to undertake natural history research. By the mid-20th century, the research fund of the Colonial Office in London had grown to one million pounds sterling annually.2 While the EIC’s primary agenda for natural history research was to maximise the company’s profit, naturalists and scientists were also motivated by the prospect of expanding the frontiers of science.3

European Study and Patronage

The naturalists conducting research in Southeast Asia had strong connections to Europe and often built on the study and collecting work of others in the same line of work. Naturalists would donate or sell their specimens in Europe and elsewhere to be stored and displayed in museums and research collections for further study. This enabled other naturalists to examine the region’s flora and fauna remotely without having to leave Europe at all.

The collections of the famed naturalist Alfred Russel Wallace were extensively studied across Europe, where he sold many of his specimens in order to fund his expeditions. While best known for his work on the theory of evolution, jointly published with Charles Darwin in 1858,4 he is better remembered in this region for his research into the natural history of the Malay Archipelago. He spent eight years, from 1854 to 1862, exploring present-day Malaysia, Singapore and Indonesia, collecting and recording – by his own count – more than 125,000 species of wildlife.5

A photograph of Alfred Russel Wallace taken in Singapore, 1862. Image reproduced from Marchant, J. (1916). Alfred Russel Wallace: Letters and Reminiscences (vol. I, between pp. 36 and 37). London, New York, Toronto and Melbourne: Cassell and Company. Retrieved from Biodiversity Heritage Library website.

A photograph of Alfred Russel Wallace taken in Singapore, 1862. Image reproduced from Marchant, J. (1916). Alfred Russel Wallace: Letters and Reminiscences (vol. I, between pp. 36 and 37). London, New York, Toronto and Melbourne: Cassell and Company. Retrieved from Biodiversity Heritage Library website.

While in Singapore, Wallace spent a significant amount of time collecting over 700 species of beetles in the Dairy Farm and Bukit Timah areas. In his letters and his 1869 book, The Malay Archipelago, Wallace provides interesting perspectives on Singapore’s natural landscape in the mid-19th century, lamenting that the virgin forest in the suburbs had been entirely cleared for nutmeg and areca palm plantations, resulting in a dearth of insect life. Naturalists at the time were studying native biodiversity in a region that was experiencing rapid deforestation to make way for plantation agriculture. Their research and records have since become invaluable documentation of species that are now locally or globally extinct.

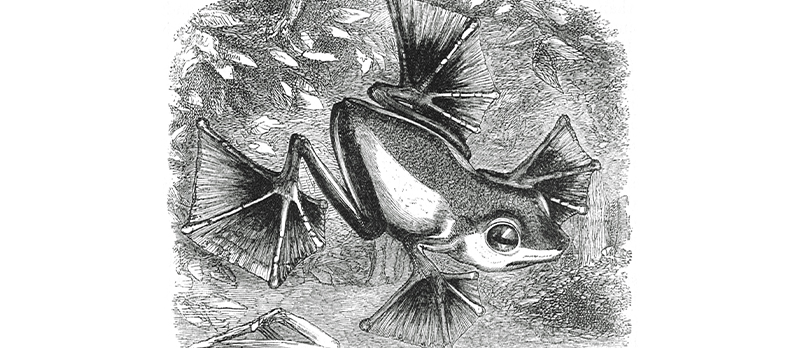

Wallace discovered and identified the gliding tree frog, Rhacophorus nigropalmatus, also known as Wallace’s flying frog. It is found in Malaysia, Borneo and Sumatra. Image reproduced from Wallace, A.R. (1874). The Malay Archipelago: The Land of the Orang-utan, and the Bird of Paradise; a Narrative of Travel, with Studies of Man and Nature (p. 38). London: Macmillan. Retrieved from BookSG. Collection of the National Library, Singapore. (Call no.: RRARE 915.9804 WAL; Accession no.: B18835319E).

Wallace discovered and identified the gliding tree frog, Rhacophorus nigropalmatus, also known as Wallace’s flying frog. It is found in Malaysia, Borneo and Sumatra. Image reproduced from Wallace, A.R. (1874). The Malay Archipelago: The Land of the Orang-utan, and the Bird of Paradise; a Narrative of Travel, with Studies of Man and Nature (p. 38). London: Macmillan. Retrieved from BookSG. Collection of the National Library, Singapore. (Call no.: RRARE 915.9804 WAL; Accession no.: B18835319E).

Part of Wallace’s collection of beetles was eventually sold to the French entomologist and natural history dealer Henri Deyrolle. His father, Jean-Baptiste Deyrolle, established a business dealing in taxidermy and specimens in Paris in 1831. Today, Maison Deyrolle serves as a museum of natural history and a cabinet of curiosities open to the public.6

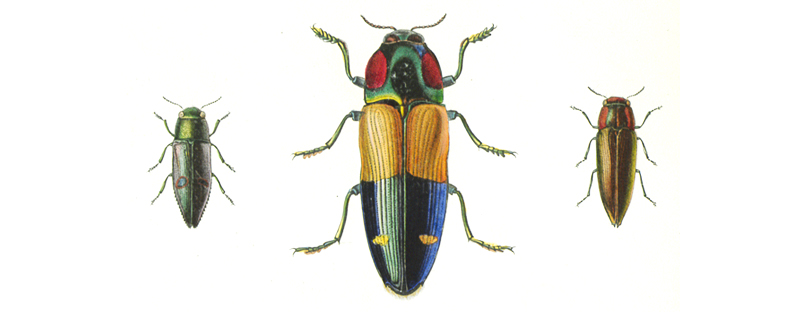

Henri Deyrolle had procured a collection of buprestidae – jewel beetles highly prized by collectors for their glossy, iridescent colours – obtained by Wallace in Malaya. The former subsequently published an essay providing detailed descriptions of these beetles in the Annales de la Société Entomologique de Belgique in 1864.7 Being the first published author to describe several of the species, Deyrolle had the privilege of naming them. He named the beetle Calodema wallacei in Wallace’s honour.8

French entomologist and natural history dealer Henri Deyrolle named the beetle species Calodema wallacei (centre) after Alfred Russel Wallace, whose collection he was studying. Images reproduced from Deyrolle, H. (1864). Description des buprestides de la Malaisie (plate II). Brussels, Paris: [n.p.]. Retrieved from BookSG. Collection of the National Library, Singapore. (Call no.: RRARE 595.763095951 DEY-[SEA]; Accession no.: B20395528A).

French entomologist and natural history dealer Henri Deyrolle named the beetle species Calodema wallacei (centre) after Alfred Russel Wallace, whose collection he was studying. Images reproduced from Deyrolle, H. (1864). Description des buprestides de la Malaisie (plate II). Brussels, Paris: [n.p.]. Retrieved from BookSG. Collection of the National Library, Singapore. (Call no.: RRARE 595.763095951 DEY-[SEA]; Accession no.: B20395528A).

Naturalists of the British East India Company

By the turn of the 19th century, the EIC had amassed an extensive collection of all manner of all manner of cultural artefacts, books, valuables and natural history specimens from across the globe. These items were collected not only for their value or for profit, but also for the acquisition of control and power over colonised nations. Francis Rawdon-Hastings, First Marquess of Hastings and the Governor-General of Bengal, was an avid supporter of the company’s ambitions to acquire knowledge. In 1799, he wrote that the company had “joined a desire to add the acquisition of knowledge… to the power, the riches, and the glory which its acts have already so largely contributed to the British Empire and Name”.9

Stamford Raffles was a significant contributor to the knowledge gathering effort. A self-styled naturalist, most of his contributions to the study of natural history were the result of hiring and commissioning naturalists and artists to collect and draw specimens. One would be hard-pressed to name a well-known naturalist in Southeast Asia in the early 1800s not connected to Raffles in some way.

American physician and naturalist Thomas Horsfield, who was employed as a surgeon by the Dutch East India Company in Batavia (now Jakarta) in 1801, began conducting his natural history research in the region. When the British wrested control of Java from the Dutch in 1811, Horsfield befriended the newly minted Lieutanant-Governor of Java Stamford Raffles, who commissioned him to research and collect specimens.10 Horsfield went on to collect and describe hundreds of species of flora and fauna.

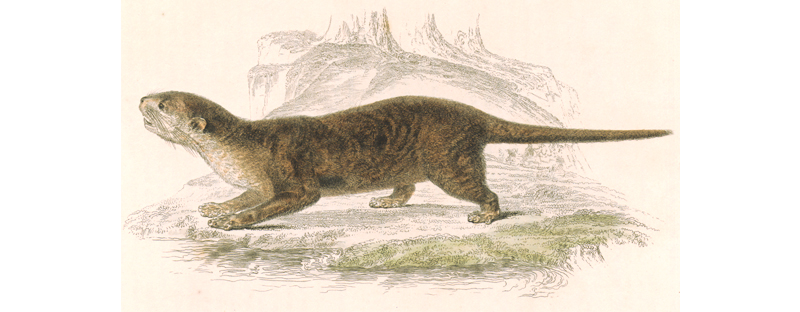

In his book Zoological Researches in Java, and the Neighbouring Islands, published in 1824,11 Horsfield describes over 70 different mammals and birds, some of which he had identified and classified for the first time. As a result, several species he found in Southeast Asian were named after him, for example the Javanese flying squirrel (Iomys horsfieldii) and Horsfield’s fruit bat (Cynoterus horsfieldii). Many of the specimens he collected, along with his publications, were donated to the East India Company Museum in London where he later took up the appointment of curator in 1819.12

American physician and naturalist Thomas Horsfield conducted natural history research in Southeast Asia when he was employed as a surgeon by the Dutch East India Company in Batavia (now Jakarta) in 1801. One of the mammals he described is the small-clawed otter shown here. These mammals are native to Singapore but are now rarely seen as a result of habitat loss, unlike the smooth-coated otters which have become prevalent in recent years. Image reproduced from Horsfield, T. (1824). Zoological Researches in Java, and the Neighbouring Islands. London: Printed for Kingsbury, Parbury, & Allen. Retrieved from BookSG. Collection of the National Library, Singapore. (Call no.: RRARE 591.9922 HOR; Accession no.: B03013680J).

American physician and naturalist Thomas Horsfield conducted natural history research in Southeast Asia when he was employed as a surgeon by the Dutch East India Company in Batavia (now Jakarta) in 1801. One of the mammals he described is the small-clawed otter shown here. These mammals are native to Singapore but are now rarely seen as a result of habitat loss, unlike the smooth-coated otters which have become prevalent in recent years. Image reproduced from Horsfield, T. (1824). Zoological Researches in Java, and the Neighbouring Islands. London: Printed for Kingsbury, Parbury, & Allen. Retrieved from BookSG. Collection of the National Library, Singapore. (Call no.: RRARE 591.9922 HOR; Accession no.: B03013680J).

Raffles also employed two young French naturalists – Alfred Duvaucel and Pierre Médard Diard – who were on board the Indiana when Raffles and William Farquhar made landfall in Singapore in January 1819. Diard and Duvaucel accompanied Raffles around the region and subsequently amassed a large collection of specimens. Together, they captured, dissected and ate a dugong (Dugong dugon) while on a natural history expedition in Sumatra in 1819.13 Specimens were sent to London, where British surgeon Everard Home illustrated and described the animal’s skeleton and organs in a paper read before the Royal Asiatic Society in London in 1820. The stuffed animals, skins and skeletons collected by the two Frenchmen, including the drawings they had commissioned, are currently housed in the Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle in Paris.14

Indigenous Knowledge

European naturalists and authors were connected by an exclusive scientific fraternity of universities, scientific organisations and historical societies that depended on a system of publishing and peer review. Authors who were a part of this system enjoyed the patronage of royalty, governments and businesses such as the EIC that were invested in their research.

However, this privileged access, primarily available to white men with a European education, the means to travel and connections that allowed them to publish their work, marginalised indigenous communities and their knowledge systems which had been passed down mainly from one generation to another rather than through published works. As a result, indigenous knowledge and understanding of the environment faced obstacles in being widely disseminated or accepted as mainstream science.15 Hence, almost all extant printed materials from the 17th to 19th centuries documenting indigenous knowledge of the region originated from European naturalists.

Yet these Europeans consistently relied on indigenous knowledge and expertise to navigate the region, collect specimens, and identify and name species as well as their respective properties and uses. In other words, close collaboration with local communities was crucial for their research and data collection.16 However, non-European sources were rarely, if ever, credited, as these were usually regarded as objects of study, rather than sources of credible information. European authors often derided indigenous knowledge as unscientific and superstitious.

John Desmond Gimlette’s 1915 book, Malay Poisons and Charm Cures, is an example of simultaneously relying on indigenous knowledge while devaluing it at the same time.17 In his foreword to Gimlette’s book, W.H. Wilcox, then Medical Adviser to the Home Office in London, disparaged the knowledge and experience of the Malay bomoh (shamans and medical practitioners) as primitive and clouded by black magic:

“[A]n especial and absorbing interest is attached to a description of medicine as practised in a country into which modern medicine has not yet penetrated, for one is carried back to the times far distant when in one’s own country the practitioners of medicine were striving to see light amidst the medley of faith cures, charms, herbal and animal remedies which has formed the Materia Medica of their forefathers.”18

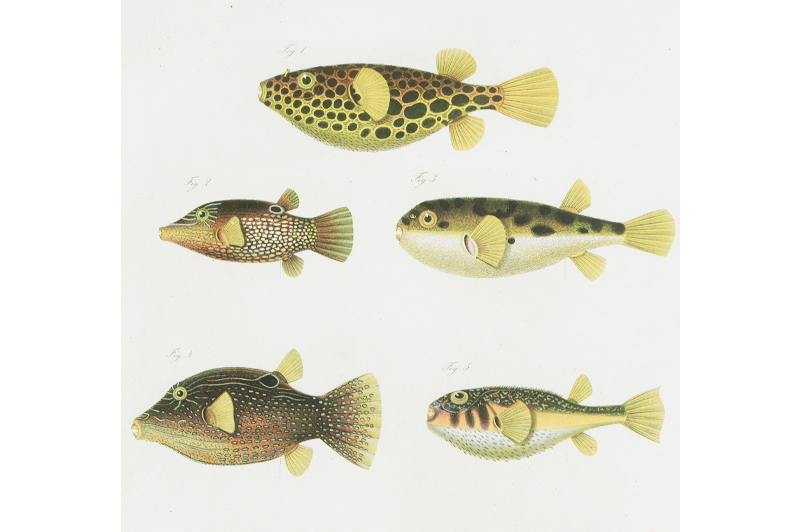

However, a chapter of the book that is dedicated to poisons obtained from fish such as the pufferfish (also called globefish, balloonfish and blowfish) clearly demonstrates the value of indigenous knowledge. Gimlette describes various species of pufferfish along with their Malay names, complete with anecdotes on poisonings and known antidotes. He also lists instructions on how to prepare the fish to render it safe for consumption. Such valuable, hard-won information could only have come from indigenous guides. In the book, Gimlette did, however, credit his primary sources of information – two bomoh of the Kelantanese royal court, Hadji Awang and Enche’ Harun bin Seman.19

John Desmond Gimlette’s book, Malay Poisons and Charm Cures, devotes a chapter to poisons obtained from fish such as the pufferfish. Shown here are illustrations of the pufferfish by the Dutch ichthyologist, Pieter Bleeker. Images reproduced from Bleeker, P. (1865 ). Atlas Ichtyologique des Indes Orientales Néêrlandaises: Publié sous les auspices du Gouvernement Colonial Néêrlandais (vol. V; CCXIII). Imprimerie de De Breuk & Smits. Retrieved from BookSG. Collection of the National Library, Singapore. (Call no.: RRARE 597.09598 BLE; Accession no.: B18975254H).

John Desmond Gimlette’s book, Malay Poisons and Charm Cures, devotes a chapter to poisons obtained from fish such as the pufferfish. Shown here are illustrations of the pufferfish by the Dutch ichthyologist, Pieter Bleeker. Images reproduced from Bleeker, P. (1865 ). Atlas Ichtyologique des Indes Orientales Néêrlandaises: Publié sous les auspices du Gouvernement Colonial Néêrlandais (vol. V; CCXIII). Imprimerie de De Breuk & Smits. Retrieved from BookSG. Collection of the National Library, Singapore. (Call no.: RRARE 597.09598 BLE; Accession no.: B18975254H).

Mohamed Haniff and Henry Ridley

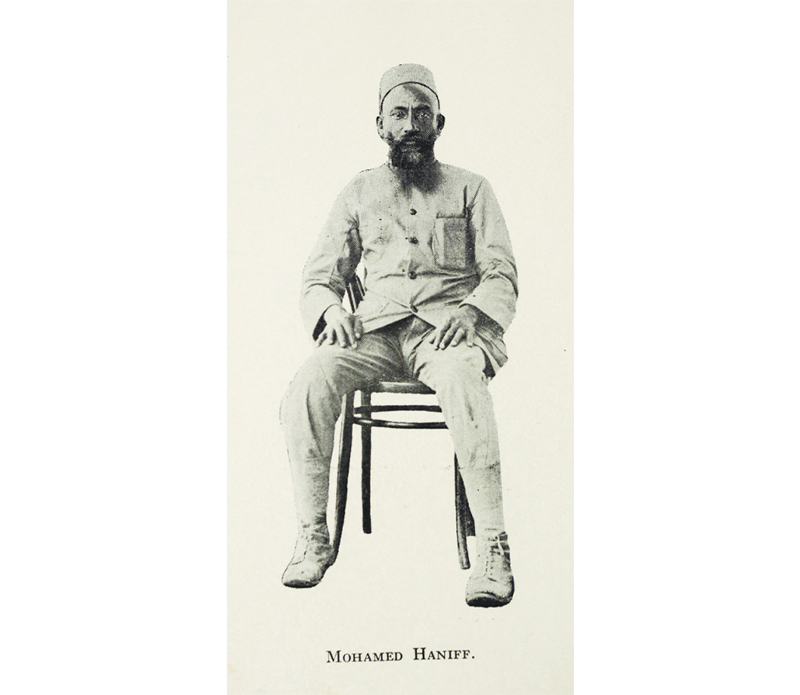

One of the rare works that credits a Malayan botanist as co-author is Malay Village Medicine, published in The Gardens’ Bulletin Straits Settlements in April 1930. It was written by Mohamed Haniff, Field Assistant and one-time Overseer of the Penang Botanic Gardens, and Isaac Burkill, then Director of the Botanic Gardens in Singapore. Long-time collaborators Burkill and Haniff toured the Malay Peninsula, extensively consulting bomoh and bidan (midwives) about local medicine and collecting plant samples to deposit in the gardens’ herbarium.20

Portrait of Mohamed Haniff, Field Assistant and one-time Overseer of the Penang Botanic Gardens. Mohamed Haniff, who died on 25 March 1930, co-wrote Malay Village Medicine with Isaac Burkill, then Director of the Botanic Gardens in Singapore, This was published in The Gardens’ Bulletin Straits Settlements in April 1930, and is one of the rare works that credits a Malayan botanist as co-author. Image reproduced from Mohamed Haniff Obituary (1930, June). The Gardens’ Bulletin Straits Settlements, 5 (3–6), 161–162, p. 161. Retrieved from Biodiversity Heritage Library website.

Portrait of Mohamed Haniff, Field Assistant and one-time Overseer of the Penang Botanic Gardens. Mohamed Haniff, who died on 25 March 1930, co-wrote Malay Village Medicine with Isaac Burkill, then Director of the Botanic Gardens in Singapore, This was published in The Gardens’ Bulletin Straits Settlements in April 1930, and is one of the rare works that credits a Malayan botanist as co-author. Image reproduced from Mohamed Haniff Obituary (1930, June). The Gardens’ Bulletin Straits Settlements, 5 (3–6), 161–162, p. 161. Retrieved from Biodiversity Heritage Library website.

The publication contains a glossary of plant species, complete with their Malay names. The authors note that according to Malay naming convention, many plants were named for their properties and uses instead of their physical characteristics – resulting in plants with wildly different appearances sharing similar names. According to Burkill, this led European naturalists who only understood plants but not Malay knowledge systems, attributing perceived inaccuracies to their Malay sources.21

Haniff was an extremely prolific botanist and collector. Armed with an extensive knowledge of Malayan flora, he was frequently relied upon to source for plants and collect information from indigenous communities. Despite having worked with several prominent European botanists, Haniff was never promoted beyond the rank of Field Assistant.22

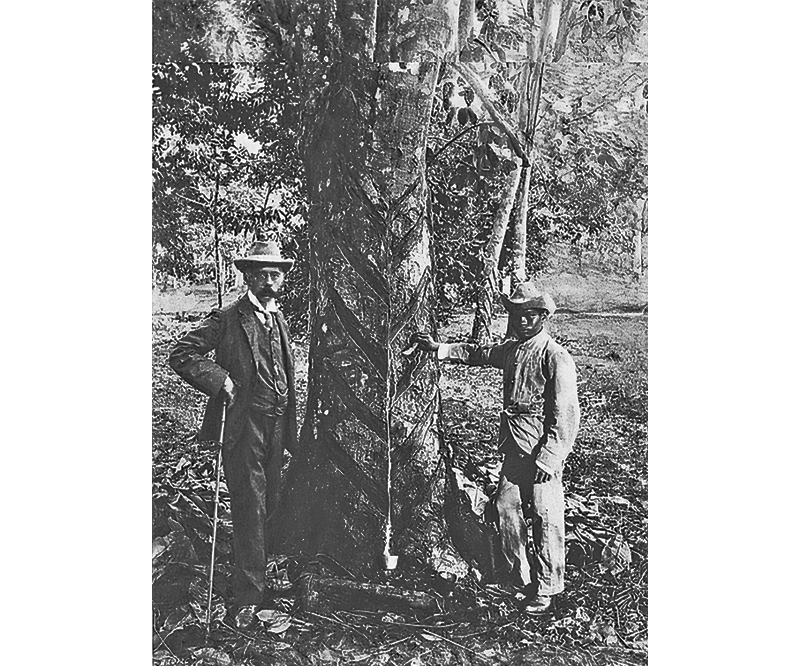

Haniff was one of many Malayan botanists working at the Botanic Gardens in Singapore, all of whom reported to European directors such as Henry Nicholas Ridley, the first director who served from 1888 to 1912. Ridley’s tenure heralded an era of intense botanical exploration and specimen collecting across Singapore and the Malay Peninsula. Much of the work was undertaken by Malayan collectors and herbarium assistants who accompanied European botanists in the field.23

Henry Nicholas Ridley (left), Director of the Singapore Botanic Gardens (1888–1912), posing with his Malay assistant beside a rubber tree in the Economic Garden. The herringbone incision patterns are clearly visible on the tree trunk. He invented this method which allowed rubber trees to be tapped at regular intervals without causing damage to the trees. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Henry Nicholas Ridley (left), Director of the Singapore Botanic Gardens (1888–1912), posing with his Malay assistant beside a rubber tree in the Economic Garden. The herringbone incision patterns are clearly visible on the tree trunk. He invented this method which allowed rubber trees to be tapped at regular intervals without causing damage to the trees. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

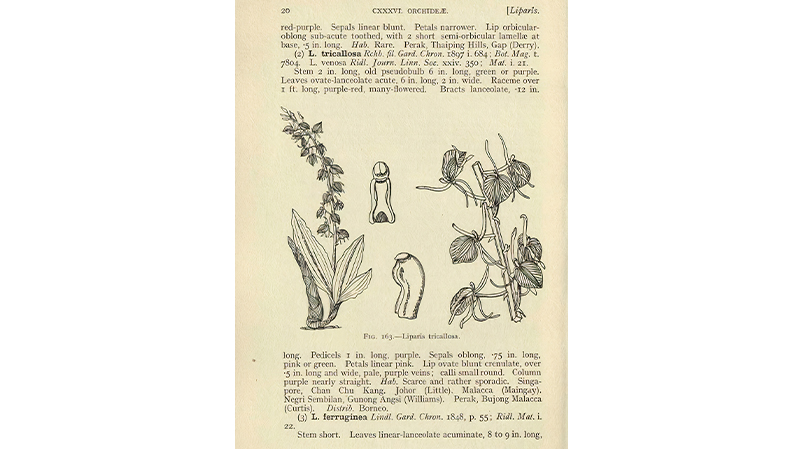

During this period, a huge volume of research on the region’s flora was produced, much of which appears in Ridley’s landmark five-volume work, The Flora of the Malay Peninsula, published between 1922 and 1925 after his retirement as director.24 Ridley’s book helped establish Singapore’s position as a centre for botanical research in the region and facilitated the transfer of many botanical specimens from Singapore to the Kew Gardens Herbarium, from which he based his research.25

Henry Nicholas Ridley published his landmark five-volume work, The Flora of the Malay Peninsula, after his retirement. Published between 1922 and 1925, the work is a record of his reasearch on the region’s flora. Shown here are illustrations of the Liparis tricallosa, a type of orchid. Image reproduced from Ridley, H.N. (1922). The Flora of the Malay Peninsula (vol. I; p. 20). London: L. Reeve & Co., Ltd. Collection of the National Library, Singapore. (Call no.: RRARE 581.9595 RID; Accession no.: B03006199F).

Henry Nicholas Ridley published his landmark five-volume work, The Flora of the Malay Peninsula, after his retirement. Published between 1922 and 1925, the work is a record of his reasearch on the region’s flora. Shown here are illustrations of the Liparis tricallosa, a type of orchid. Image reproduced from Ridley, H.N. (1922). The Flora of the Malay Peninsula (vol. I; p. 20). London: L. Reeve & Co., Ltd. Collection of the National Library, Singapore. (Call no.: RRARE 581.9595 RID; Accession no.: B03006199F).

One of Ridley’s objectives in publishing his book was to generate interest in the economic and scientific potential of the flora of Southeast Asia. However, the colonial authorities and the public found his work dense and overly scientific, with little application to their interests, which were primarily economic.26 His successor, Isaac Burkill, reorganised the herbarium’s collection and later produced a more accessible work, the two-volume A Dictionary of the Economic Products of the Malay Peninsula (1935), which framed plant “discoveries” in terms of their usefulness and economic value.27

Another of Ridley’s legacies would have a profound impact on the global economy and the landscape of the region. He experimented with developing a more sustainable method of latex extraction from rubber trees called the “herringbone technique” that allowed the trees to be tapped at regular intervals without causing long-term damage to them.

His subsequent relentless promotion of the commercial value of rubber and the large-scale introduction of the tree in Malaya spurred the growth of the rubber industry in Malaya.28 By the 1930s, Malaya had become the world’s largest rubber producer, with rubber plantations sprouting up across Singapore and the peninsula. “Everyone went mad”, said Ridley. “Every bit of waste ground, orchards and even gardens were planted [with rubber trees]. No one talked of anything else.”29

The study of Southeast Asia’s natural history has been driven by many factors, including colonialism, territorial expansion and the European pursuit of knowledge. This perception of nature, shaped primarily by collection, classification and ultimately profit, paved the way for the large-scale exploitation and transformation of the landscape of Singapore and the region.

Georgina Wong is a Curator with Programmes & Exhibitions at the National Library, Singapore. She is co-curator of the “Human x Nature: Environmental Histories of Singapore” exhibition.

Georgina Wong is a Curator with Programmes & Exhibitions at the National Library, Singapore. She is co-curator of the “Human x Nature: Environmental Histories of Singapore” exhibition.

NOTES

-

In Alfred Russel Wallace’s letter to Edward Newman. Newman was an English entomologist and botanist, and editor-in-chief of the natural history magazine, The Zoologist. See Van Wyhe, J., & Rookmaaker, R. (Eds.). (2013). Alfred Russel Wallace: Letters from the Malay Archipelago (p. 286). Oxford: Oxford University Press. (Call no.: RSEA 508.092 WAL) ↩

-

Clarke, S. (2011). The chance to send their first class men out to the colonies: The making of the colonial research service (p. 188). In B.M. Bennett & J.M. Hodge (Eds.), Science and empire: Knowledge and networks of science across the British Empire, 1800–1970 (pp. 187–208). Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire; New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan. (Call no.: R 509.171241 SCI) ↩

-

For more information on the British East India Company and their activities regarding the environment of the region, see Damodaran, V., Winterbottom, A., & Alan, L. (Eds.). (2015) The East India Company and the natural world. Houndsmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire, UK: Palgrave Macmillan. (Call. no.: RSEA 508.54 EAS) ↩

-

Darwin, C., & Wallace, A. (1858, August). On the tendency of species to form varieties; and on the perpetuation of varieties and species by natural means of selection. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, 3 (9), 45–62. Retrieved from Wiley Online Library. ↩

-

Wallace, A.R. (1869). The Malay archipelago: The land of the orang-utan, and the bird of paradise; a narrative of travel, with studies of man and nature (vol. I; p. vii). London: Macmillan. (Call no.: RRARE 915.9804 WAL; Accession no.: B03013900E). [Note: NLB has digitised the 1874 edition. See Wallace, A.R. (1874). The Malay Archipelago: The land of the orang-utan, and the bird of paradise; a narrative of travel, with studies of man and nature. London: Macmillan. Retrieved from BookSG. (Call no.: RRARE 915.9804 WAL; Accession no.: B18835319E) ↩

-

Deyrolle. (2021). Deyrolle La Boutique En Ligne. Retrieved from Deyrolle website. ↩

-

Deyrolle, H. (1864). Description des buprestides de la Malaisie (pp. vi–vii). Brussels, Paris: [n.p.]. Retrieved from BookSG. (Call no.: RRARE 595.763095951 DEY-[SEA]; Accession no.: B20395528A); Deyrolle, H. (1864). Description des buprestides de la Malaisie Receuillis par M. Wallace. Annales de la Société Entomologique de Belgique, 8, 1–269, p. iii. Retrieved from Biodversity Heritage Library website. ↩

-

Deyrolle, 1864, pp. vi–vii, plate II. ↩

-

Desmond, R. (1982). The India Museum, 1801–1879 (p. 13). London: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office. (Call no.: RCLOS 069.0954 DES-[JSB]) ↩

-

Bastin, J. (2019). Sir Stamford Raffles and some of his friends and contemporaries: A memoir of the founder of Singapore (pp. 135–137). Singapore: World Scientific Publishing Co. Pte Ltd. (Call no.: RSING 959.5703092 BAS-[HIS]) ↩

-

Horsfield, T. (1824). Zoological researches in Java, and the neighbouring islands. London: Printed for Kingsbury, Parbury, & Allen. Retrieved from BookSG. (Call no.: RRARE 591.9922 HOR; Accession no.: B03013680J) ↩

-

Pocklington, K., & Low, M. (2019). 200: Points in Singapore’s natural history. Singapore: Lee Kong Chian Natural History Museum. (Call no.: RSING 508.5957 LOW); Home, E. (1820, April 13). On the milk tusks, and organ of hearing of the dugong. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London for the Year 1820, Part II, 144–55. London: W. Bulmer and W. Nicol. (Call no.: RRARE 599.556 PHI-[JSB]; Accession no.: B29268003H) ↩

-

Weiler, D. (2020, Jul–Sep). Stamford Raffles and the two French naturalists. BiblioAsia, 16 (2), 4–9. Retrieved from BiblioAsia website. ↩

-

Ikechi, M. (2006). Global biopiracy: Patents, plants and indigenous knowledge (pp. 10–13). Vancouver, British Columbia: UBC Press. Retrieved from ProQuest Ebook Central via NLB’s eResources website. ↩

-

Damodaran, Winterbottom & Alan, 2015, pp. 18–20, 29–30. ↩

-

Gimlette, J.D. (1915). Malay poisons and charm cures. London: J. & A. Churchill. (Call no.: RRARE 398.4 GIM-[JSB]; Accession no.: B29267423B). [Note: NLB has digitised the second edition. See Gimlette, J.D. (1923). Malay poisons and charm cures. London: J. & A. Churchill. Retrieved from BookSG. (Call no.: RRARE 398.4 GIM; Accession no.: B02993050F)] ↩

-

Burkill, I.H., & Mohamed Haniff. (1930, April). Malay village medicine. The Gardens’ Bulletin Straits Settlements, 6 (6–10), 165–321, p. 165. Singapore: Botanic Gardens. (Call no.: RDTYS 615.3209595 BUR) ↩

-

Burkill & Mohamed Haniff, Apr 1930, p. 166. ↩

-

Mohamed Haniff obituary. (1930, June). The Gardens Bulletin Straits Settlements, 5 (3–6), 161–162, p. 161. Retrieved from Biodiversity Heritage Library website. ↩

-

A large volume of letters along with Henry Nicholas Ridley’s own field notes document the everyday work of the Singapore Botanic Gardens. These can be accessed at the Biodiversity Heritage Library website. ↩

-

Ridley, H.N. (1922–25). The flora of the Malay Peninsula (5 volumes). London: L. Reeve & Co., Ltd. (Call no.: RRARE 581.9595 RID; Accession nos.: B03006199F [vol. I], B03006198E [vol. II], B03006197D [vol. III], B03006204D [vol. IV], B03006203C [vol. V]) ↩

-

Barnard, T. (2016). Nature’s colony: Empire nation and environment in the Singapore Botanic Gardens (p. 181). Singapore: NUS Press. (Call no.: RSING 580.735957 BAR) ↩

-

Burkill, I.H. (1935). A dictionary of the economic products of the Malay Peninsula. London: Published on behalf of the Governments of the Straits Settlements and Federated Malay states by the Crown Agents for the Colonies. (Call no.: RCLOS 634.909595 BUR) ↩

-

Tinsley, B. (2009). Gardens of perpetual summer: The Singapore Botanic Gardens (pp. 41–42). Singapore: National Parks Board, Singapore Botanic Gardens. (Call no.: RSING 580.735957 TIN); Tan, P.W.C., Tan, A.L., & Lau, L. (2015). Singapore rubber trade: An economic heritage (pp. 41–42). Singapore: Suntree Media Pte Ltd. (Call no.: RSING 338.476782095957 TAN) ↩

-

Ridley found a way to tap rubber and gave Malaya its wealth. (1953, November 21). The Straits Times, p. 9. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩