Early Printing in the Philippines

Continuing with the series on printing in Southeast Asia, Gracie Lee explores the early history of printing and printed works in the Philippines.

The spread of printing in Southeast Asia is closely intertwined with European colonisation and the arrival of missionaries in the region from the 16th century onwards. While the time-honoured art of woodblock printing (known also as xylography) had been used in Vietnam as early as the 11th century,1 book printing was unknown in the rest of Southeast Asia where oral and manuscript traditions had existed for centuries.2 The emergence of a print culture in the Philippines is particularly fascinating as it chronicles the transnational and cross-cultural transfer of printing knowledge among the Europeans, the Chinese and indigenous Filipinos within colonial Filipino society and economy.

Beginnings of Printing in the Philippines

According to the earliest written accounts of the history of the country, pre-colonial Philippines was a literate society with an indigenous writing system. In Relación de las Islas Filipinas (1604), one of the earliest works about the Philippines and its people, Spanish Jesuit priest and historian Pedro Chirino wrote: “All these islanders are much given to reading and writing and there is hardly a man, and much less a woman, who does not read and write in the letters used in the island of Manila.”3 These writings were inscribed on perishable materials such as tree bark, leaves and bamboo tubes.4

Printing came on the heels of the spread of Christianity and Spanish colonisation during the 16th century. Although the beginnings of the first printing press in Philippines are obscure, most scholars agree that the Dominicans, a Roman Catholic order, were the first to start printing in the Philippines. Much of the early printed literature in the Philippines consisted of catechism and language instructional texts published by various Catholic religious orders operating in the Philippines such as the Franciscans, the Jesuits and the Augustinians.5

Oldest Known Book Printed in the Philippines

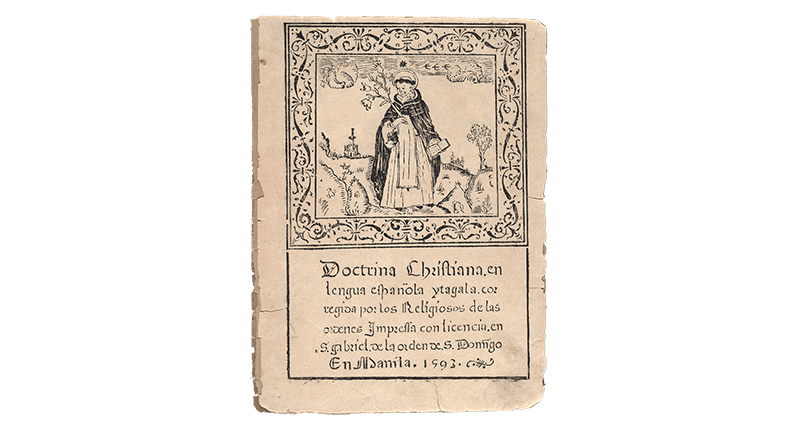

The Doctrina Christiana (Christian Doctrine) is widely accepted as the oldest surviving book printed in the Philippines. This publication of Catholic teachings was printed in 1593 using the xylographic method in two editions. The version in Spanish-Tagalog was written for the local Filipino population and is attributed to Franciscan friar Juan de Plasencia, whose translation was approved by the diocesan synod in 1582. The second was produced in Chinese for the conversion of the Chinese community in the Parián,6 a commercial enclave of Manila.

In a letter from the governor-general of the Philippines, Gómez Pérez Dasmariñas, to King Philip II of Spain dated 20 June 1593, Dasmariñas wrote that because of the existing great need, “he had granted a licence for the printing of the Doctrinas Christianas, herewith enclosed – one in the Tagalog language, which is the native and best of these islands, and the other in Chinese – from which I hope great benefits will result in the conversion and instruction of the peoples of both nations; and because the lands of the Indies are on a larger scale in everything and things more expensive, I have set the price of them at four reales a piece, until Your Majesty is pleased to decree in full what is to be done”.7

Printing permits were required as books were a tightly controlled commodity during Spanish rule (1565–1898) in the Philippines. In 1556, a royal cedula (decree) was issued prohibiting the sale of books about the East Indies without a special licence.

In 1583, the Commissary of the Holy Office in Manila was instructed to inspect and seize imported books of prohibited titles. Restrictions were extended the following year such that “when any grammar or dictionary of the language of the Indies be made, it shall not be published or printed or used unless it has first been examined by the Bishop and seen by the Royal Audiencia [the colonial court]”.8

Up until the mid-20th century, there were two known versions of the Doctrina Christiana in existence – a Spanish-Tagalog edition held at the Library of Congress titled Doctrina Christiana, en Lengua Española y Tagala (Christian Doctrine in Spanish and Tagalog Languages) printed at the Dominican Church of San Gabriel in Manila, and an undated Chinese edition found in the Vatican Library titled Doctrina Christiana en Letra y Lengua China (Christian Doctrine in the Chinese Language and Letters) compiled by Dominican priests ministering among the Sangleys (people of mixed Chinese and Filipino ancestry) and printed by Keng Yong, a Chinese living in the Parián district of Manila. In the absence of other known copies, these two texts were thought to be the ones referred to in the governor-general’s letter.9

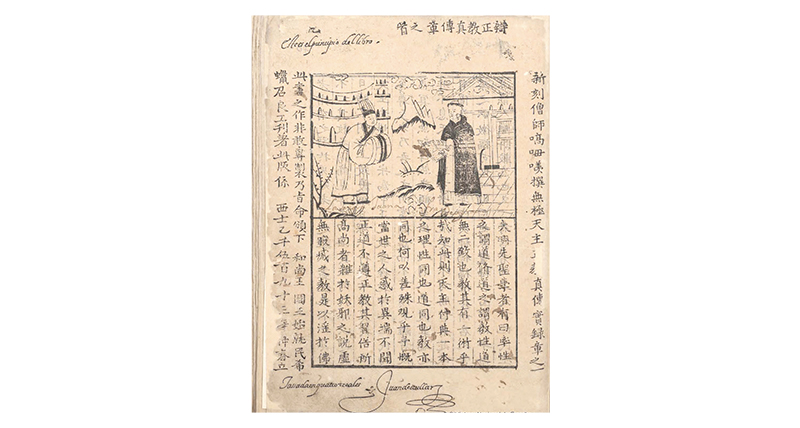

In 1952, however, the discovery of another Chinese version at the Biblioteca Nacional de España (National Library of Spain) rippled across the scholarly community. Titled (《新刻僧師高母羡撰無極天主正教真傳實錄》Xin Ke Seng Shi Gao Mu Xian Zhuan Wuji Tianzhu Zhengjiao Zhenchuan Shilu; A Printed Edition of the Veritable Record of the Authentic Tradition of the True Faith in the Infinite God, by the Religious Master Kao-mu Hsien), also known as (《辯正教真傳實錄》Bian Zhengjiao Zhenchuan Shilu, Testimony of the True Religion), the work was written by Dominican friar Juan Cobo, who arrived in Manila in 1588. It was printed in the “second month of the spring in the year of our Lord 1593”.10

This new find has now been generally accepted as the Chinese version mentioned in the governor-general’s letter. According to Cobo, the book was “published with licence of the Bishop and the Governor” and when they first arrived in Manila, they commissioned a skilled craftsman to carve the woodblocks that were used in the printing of the book. The content takes the form of a dialogue, and was likely inspired by the dialogic exchange featured in Jesuit Michele Ruggieri’s (《天主實錄》Tianzhu Shilu; The True Record of the Lord of Heaven), the first Chinese catechism text printed in 1584.

Cobo’s work contains a mix of treatises on theology, Western cosmography and natural history accompanied by illustrations of the cosmos, planets and animals.

In this respect, it also bears similarities with another earlier work. Penned in 1583 by another Dominican friar, Fray Luis de Granada, who was a noted theologian, writer and preacher, the Introducción del Símbolo de la Fe (Introduction of the Symbol of Faith) was an attempt to explain the Christian doctrine through natural theology – an argument that evidence of intelligent design in nature points to the existence of a creator God. This approach was probably designed to appeal to learned Chinese readers as shown in the illustration of a Western scholar-priest conversing with a Chinese scholar.11

As for the copy in the Vatican Library, its provenance remains uncertain. One view contends that it predates the Doctrina Christiana in the Library of Congress and the National Library of Spain. Unlike most officially approved publications which were dated, this book was not. According to the title page it was printed with licence, but the omission of the year of publication has led some to speculate that the work was printed before the necessary permit could be secured due to the urgent need to evangelise to the Chinese community.

This view has been challenged by others who place the publication in the early 1600s based on studies of its linguistic and physical characteristics. Although its history cannot be conclusively determined, the identification of its printer, Keng Yong, throws a spotlight on the role that Chinese printers played in the development of early printing in the Philippines.12

Contributions of Early Chinese Printers

Brothers Juan de Vera and Pedro de Vera, known only by their baptismal names, were two early Chinese Christian printers involved in some of the earliest imprints found in the Philippines. Under the auspices of Francisco Blancas de San José, a Dominican priest, the first typographical press was set up by Juan de Vera in the Chinese settlement of Binondo.

In his ecclesiastical history of the Philippines, Dominican friar Diego Aduarte noted that Francisco Blancas de San José had written many books of devotion, and “since there was no printing in these islands, and no one who understood it or who was a journeyman printer, he planned to have it done through a Chinaman, a good Christian, who, seeing that the books of P. Fr. Francisco were sure to be of great use, bestowed so much care upon this undertaking that he finally succeeded, aided by those who told him whatever they knew about it, in learning everything necessary to do printing; and he printed these books”.13

The “good Christian” was Juan de Vera who was commended as being a “very devout man, and one much given to prayer… He always heard mass, and was very regular in his attendance at church.” In addition to learning to be a printer, it was also noted that he “adorned the church most handsomely with hangings and paintings, because he understood this art”.14

Other contemporaneous accounts, in addition to Aduarte’s, also described Juan de Vera as the first typographical printer in the Philippines.15 Scholarly opinions, however, remain divided on whether his role extended to local type casting (typography), or if the printing press was imported from elsewhere, such as Goa or Japan.16

The oldest extant book produced in movable type (using individual movable pieces with each carrying a single letter or character) in the Philippines is thought to be the Ordinationes Generales Provintiae Sanctissimi Rosarii Philippinarum (The General Ordinances of the Philippine Ordinances of the Philippine Province of the Holy Rosary), printed by Juan de Vera in 1604. Written in Latin, it lays out the precepts of the Dominican Province of the Rosary. Printed by order of the Provincial, Miguel Martín de San Jacinto, it has been suggested that the intent of the publication was possibly to prepare the mendicants as they head to their new mission in the Philippines.17 A copy of this work can be found in the Library of Congress.

Other notable works printed by Juan de Vera include the 1602 Libro de Nuestra Señora del Rosario en Lengua y Letra Tagala de Filipinas (Book of Our Lady of the Rosary in the Language and Letters of the Philippines), a devotional work in Tagalog, and the Libro de las Quatro Postrimerias del Hombre: En Lengua Tagala, y Letra Española (The Book on the Four Last Things of Man in Tagalog and Spanish), printed in 1604 and composed by Fray Francisco Blancas de San José.18

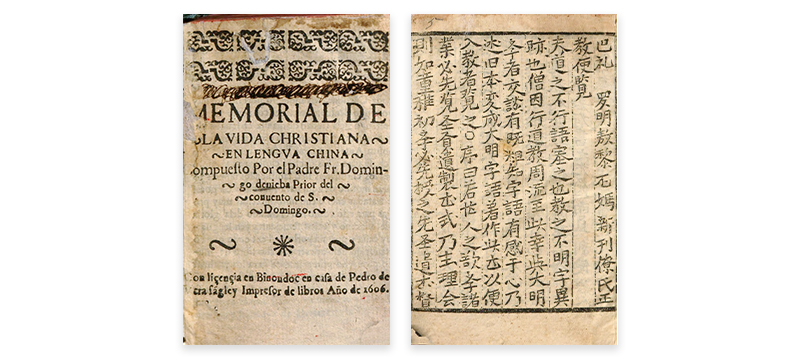

Pedro de Vera, believed to be the younger brother who assumed Juan de Vera’s responsibilities upon the latter’s death, was also behind some of the earliest imprints in the Philippines. In 1606, he printed Memorial de la Vida Christiana en Lengva China 《 新刊僚氏正教便览》; (Xinkan Liao Shi Zhengjiao Bianlan; A Printed Edition of the Guide to the True Faith in God). Written by Dominican priest, Domingo de Nieva (巴禮羅明敖黎尼媽), the book aimed to help beginners grow in their faith through the exercise of spiritual disciplines, and was modelled after Fray Luis de Granada’s guide on spiritual formation titled Memorial de la Vida Cristiana (Memorial of the Christian Life, 1565).

Pedro de Vera used a combination of Chinese and European printing methods for this book. For instance, preliminary information such as the title page, approbation, licences and dedication in Spanish were printed using movable type. The main text, preface and table of contents in Chinese were printed using woodblock printing. Copies of this two-part work can be found in the Jesuit Archives in Rome and the Österreichische Nationalbibliothek (Austrian National Library).19

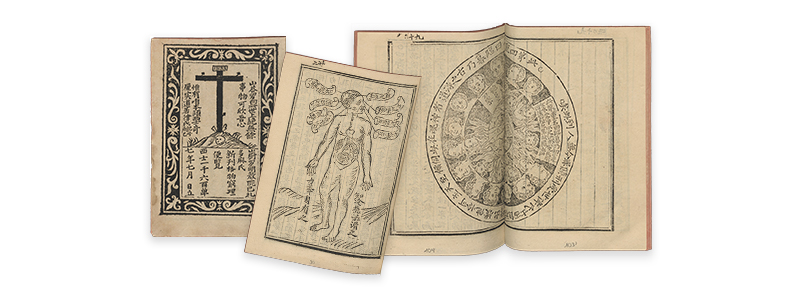

He used the same approach in another work printed in 1607, Simbolo de la Fe, en Lengua y Letra China 《新刊格物窮理錄》; (Xinkan Gewu Qiongli Lu; Newly Printed Record of the Investigation of Things and Exhaustive Examination of Principle). The preliminary information in Spanish was rendered in movable type, while the main text in Chinese and the illustrations of animals, the human anatomy and the underworld were produced using xylography.

This expository guide, composed by Dominican friar Tomás Mayor (哆媽氏), was an adaptation of Luis de Granada’s Introducción del Símbolo de la Fe (Introduction of the Symbol of Faith). Copies of Mayor’s work can be found in the Jesuit Archives in Rome, the Austrian National Library and the Leiden University Library in the Netherlands. According to the Latin inscription on one of the copies in the Jesuit Archives, the book was subsequently suspended and expurgated from circulation due to its many errors.20

The First Filipino Printer

From the early 17th century, the influence of Chinese printers began to wane as a generation of local Filipino printers emerged. Foremost among them was Tomás Pinpin, who is credited as the first Filipino printer and typesetter.21 Today, his name is enshrined throughout the Philippines – such as the Limbagang Pinpin Museum in Abucay, Tomas Pinpin Street in Manila and an early 20th-century Tomás Pinpin obelisk that stands at the Plaza San Lorenzo Ruiz in Manila.22

Pinpin was a printer and writer from Abucay, a municipality in the province of Bataan. It is commonly believed that he had learnt to print from an apprenticeship with Chinese artisans and/or Francisco Blancas de San José, who set up the first movable type press in Binondo with Juan de Vera.

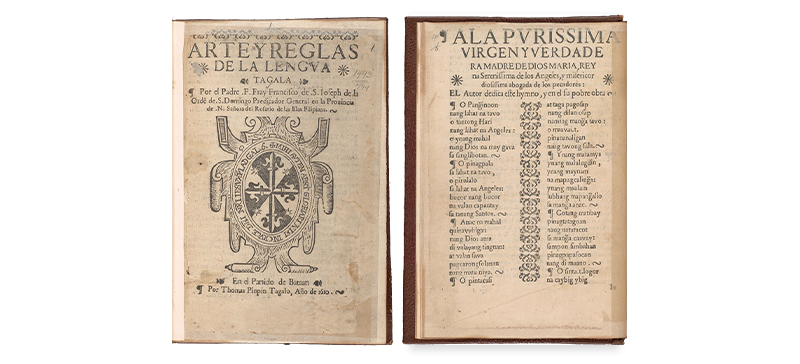

In 1608, Francisco Blancas de San José was posted to Abucay where he collaborated with Pinpin in the production of Arte y Reglas de la Lengua Tagala (Art and Rules of the Tagalog Language; 1610), the first published grammar of the Tagalog language. As the first published text of its kind, the work became a blueprint for the writing of subsequent grammar books on the native languages of the Philippines.

Pinpin and fellow Filipino printer Domingo Loag also operated the typographical printing press that the Franciscans had established in Pila, Laguna. In 1613, they printed Franciscan friar Pedro de San Buenaventura’s Vocabulario de la Lengua Tagala (Vocabulary of the Tagalog Language), the oldest surviving Tagalog dictionary.23

Pinpin’s trailblazing achievements extended beyond the realm of printing. He also authored Librong Pagaaralan nang manga Tagalog nang Uicang Castilla (Reference Book for Learning Castellano in Tagalog), celebrated as the first published work by an indigenous Filipino. Written to help fellow Filipinos learn Spanish, the guide was printed in Bataan in 1610 by Diego Talaghay, thought by some to be Pinpin’s assistant.

In 1637, Pinpin also published the booklet Sucessos Felices (Fortunate Events). The 14-page publication describes the Spanish battle with pirates in Mindanao.

It has been estimated that between 1563 and 1640, some 100 books were published in the Philippines.24

Later Developments

For much of the period between the 16th and 18th centuries, religious presses dominated the landscape of printing and publishing in the Philippines until the proliferation of the secular press in the 19th century – signalling a maturation of the printing and publishing industry in the country.

The first newspaper published in the Philippines, Gaceta del Superior Gobierno (Gazette of the High Government), made its debut on 8 August 1811. Edited by the governor-general of the Philippines, Mariano Fernández de Folgueras, the Spanish-language newspaper focused on political news in Europe that affected Spain, principally the Napoleonic Wars. However, the newspaper was not published regularly. It ceased publication after just 15 issues, with the last edition released on 7 February 1812.

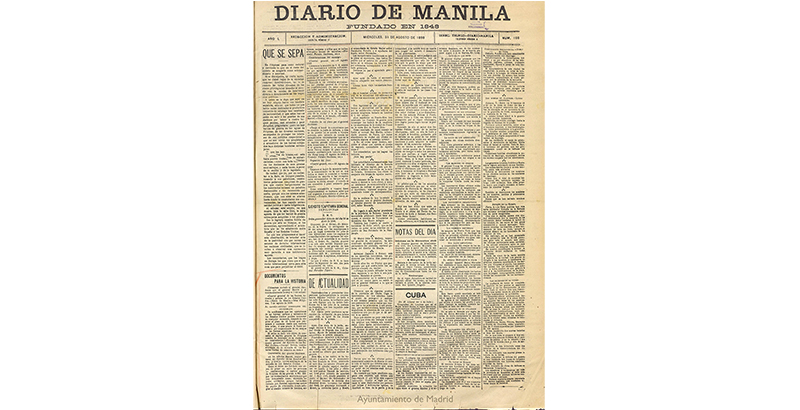

This paved the way for other Spanish-language newspapers, such as the first daily La Esperanza (1846–1849) and Diario de Manila (1848–1898?), one of the longest-running newspapers published during the Spanish colonial era. The first daily in Tagalog, Diariong Tagalog, was published in 1882.25

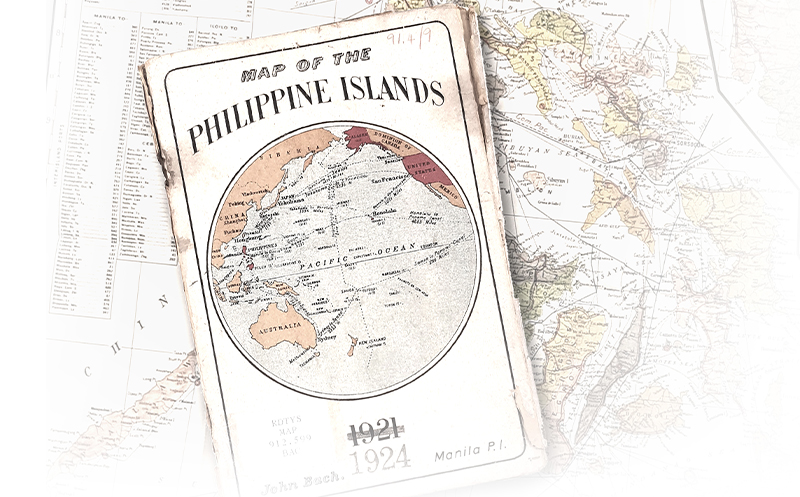

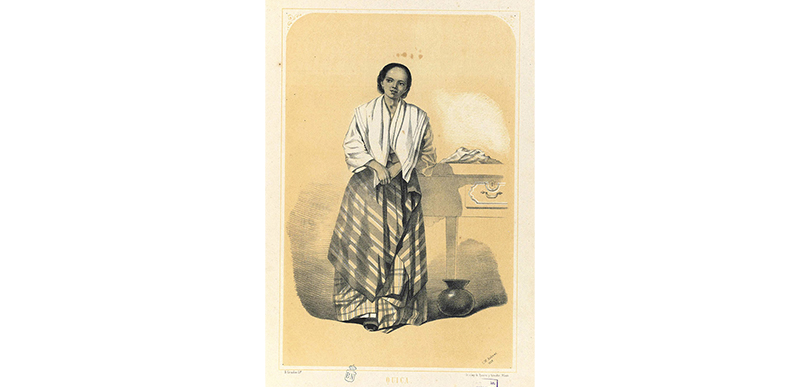

Some leading printing firms and publishing houses in the 19th century include the Imprenta y Litografía de Ramírez y Giraudier, which was established in 1858 as a lithographic printing firm, and Carmelo and Bauermann (1887–1938), a major publishing house co-founded by artist-engraver Don Eulalio Carmelo de Lakandula, and William Bauermann, a German lithographer and cartographer. Carmelo’s son Alfredo (a famous Filipino aviator), operated the firm until 1938. Collectively, both firms produced some of the most beautiful prints on the Philippines, such as the images of Filipino life and landscapes in the illustrated magazine Ilustración Filipina,26 and maps of the Philippines.

Another firm, Cacho Hermanos, which started as a printing shop set up in 1880 by the first lithographic printer in the Philippines, Salvador Chofre, is one of the longest surviving printers still in business today.

In 1901, the Bureau of Printing (today’s National Printing Office) was created to take charge of all routine government printing jobs such as government gazettes, official reports and communication materials. The emergence of commercial and government printing sets the stage for the next phase of the history of printing and publishing in the Philippines as Spanish colonial rule drew to a close, to be replaced by another colonial master, the United States, in the early 20th century.

Gracie Lee is a Senior Librarian with the National Library, Singapore. She works with the library’s rare materials collections, and her research areas include Singapore’s publishing history and the Japanese Occupation.

Gracie Lee is a Senior Librarian with the National Library, Singapore. She works with the library’s rare materials collections, and her research areas include Singapore’s publishing history and the Japanese Occupation.

RELATED ARTICLE

NOTES

-

Kornicki, P.F. (2018). Languages, scripts, and Chinese texts in East Asia (p. 117). Oxford: Oxford University Press. (Not available in NLB holdings) ↩

-

Suarez, M.F., & Woudhuysen, H.R. (Eds.). (2013). The book: A global history (pp. 624–625, 631–632). Oxford: Oxford University Press. (Call no.: 002.09 BOO) ↩

-

Wolf, E. (1947). Doctrina Christiana: The first book printed in the Philippines, Manila, 1593. Retrieved from Project Gutenberg website. ↩

-

Buhain, D.D. (1998). A history of publishing in the Philippines (p. 2). [Quezon City]: D.D. Buhain. (Call no.: R q070.509599 HIS) ↩

-

Vallejo, R.M. (n.d.). Books and bookmaking in the Philippines. Retrieved from the National Commission for Culture and Arts (Republic of the Philippines, Office of the President) website; Suarez & Woudhuysen, 2013, p. 112. ↩

-

The Parián was an area built to house Chinese merchants in Manila in the 16th and 17th centuries during the Spanish colonial period. It quickly became the commercial centre of Manila comprising the Chinese silk market and other small shops of tailors, cobblers, painters, bakers, confectioners, candle makers, silversmiths, apothecaries and other tradesmen. ↩

-

Wolf, 1947. ↩

-

Wolf, 1947; Quirino, C. (1973). Foreword (pp. iii–xi). In Doctrina Christiana: The first book printed in the Philippines, Manila, 1593. Manila: National Historical Commission. (Call no.: RSEA 094.4 DOC); Blair, E.H., Robertson, J.A., & Bourne, E.G. (1903–09). The Philippine islands, 1493–1803 (Vol. 5; p. 272). Cleveland, A.H. Clark Co. (Call no.: RSEA 959.902 BLA). ↩

-

Quirino, 1973, pp. iii–xi; Wolf, 1947; Van der Loon, P. (1966–67). The Manila incunabula and early Hokkien studies (pp. 1–25) London: P. Lund, Humphries. Retrieved from Institute of History and Philology, Academia Sinica website. ↩

-

Van der Loon, 1966–67, p. 6 ↩

-

Quirino, 1973, pp. iii–xi; Menegon, E. (2009). Ancestors, virgins, & friars: Christianity as a local religion in late Imperial China (p. 52). Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Asia Center for the Harvard-Yenching Institute. (Call no.: R 275.1245 MEN); Chan, A. (1989). A note on the Shih-lu of Juan Cobo. Philippines Studies, 37 (4), 479–487. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website; Van der Loon, 1966–1967, p. 4 ↩

-

Quirino, 1973, pp. iii–xi; Van der Loon, 1966–67, pp. 1–25; University of Michigan Library. (n.d.). Missionary writing. Retrieved from University of Michigan Library website. ↩

-

Wolf, 1947. ↩

-

Wolf, 1947. ↩

-

Wolf, 1947; Van der Loon, 1966–67, pp. 25–28. ↩

-

Van der Loon, 1966–67, pp. 25–28; Vallejo, n.d.; Lent, J.A. (1980). The missionary press of Asia, 1550–1860. Communicatio Socialis, 14 (2), 119–141, p. 120. Retrieved from Nomos eLibrary website. ↩

-

A mendicant is a member of any of several Roman Catholic religious orders who assumes a vow of poverty and supports himself or herself by work and charitable contributions. ↩

-

Van der Loon, 1966–67, pp. 25–28; De la Costa, H. (1955, June). A first printing. Philippine Studies, 3 (2), 214–216. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website. ↩

-

Van der Loon, 1966–67, pp. 28–31; Chan, A. (2002). Chinese books and documents in the Jesuit archives in Rome: A descriptive catalogue: Japonica-Sinica I-IV (pp. 226–229). Armonk, N.Y.: M.E. Sharpe. (Call no.: R q016.895108 CHA-[LIB]); Menegon, 2009, p. 52. ↩

-

Van der Loon, 1966–1967, pp. 31–39; Chan, 2002, pp. 229–230; Menegon, 2009, p. 52; Standaert, N. (1994). Heaven and hell in the 17th century exchange between China and the West. Review of Culture, (21), 83–94. Retrieved from Instituto Cultural de Macau website; Thomas, M. (1606). Simbolo de la fe, en lengua y letra China (Hsin k’an ke wu ch’iung li pien lan). Binondoc: Pedro de Vera. Retrieved from Österreichische Nationalbibliothek website. ↩

-

Gomez, B. (2020, June 18). Opinion: Celebrating Magellan plus a history lesson on Tomas Pinpin. Retrieved from ABS-CBN News website; Taylor, C. (1927). History of Philippine press (p. 3). Manila: [s.n.] Retrieved from University of Michigan Library website. ↩

-

Vibar, A.M. (2014). The 1610 Arte y reglas de a lengua tagala revisited: An advanced grammar for Spanish missionaries of the seventeenth century. Synergeia, 5 (1), 1–22. Retrieved from Philippine e-journals website; MacKinlay, W.E.W. (1905). A handbook and grammar of the Tagalog language (p. 8). Washington: Government Printing Office. Retrieved from University of Michigan Library website. ↩

-

Jurilla, P.B. (2006, August 30). Tagalog bestsellers and the history of the book in the Philippines (pp. 43–46). [A thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, no. 2768]. London: University of London (School of Oriental and African Studies). Retrieved from SOAS Research Online website; Buhain, 1998, p. 9; Vallejo, n.d.; National Historical Commission of the Philippines. (n.d.). Filipinos in history: Tomas Pinpin. Retrieved from National Historical Commission of the Philippines website; Fernandez, D.G. (1989). The Philippine press system: 1811–1989. Philippine Studies, 37 (3), 317–344, p. 318. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website. ↩

-

Buhain, 1998, pp. 19–23; Taylor, 1927, p. 3; Fernandez, 1989, 317–344; Del Carmen Pareja Ortiz, M. (1993). “Gaceta Del Superior Gobierno”: The first Philippine newspaper. Philippine Studies, 41 (2), 182–203. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website; Jurilla, 2006, pp. 53–54. ↩

-

Miguel de Benavides Library of the Universty of Santa Tomas. (n.d.). Collection 9.3 - Ilustración Filipina. Retrieved from University of Santo Tomas Miguel de Benavides Library and Archives website. ↩