Malay-Muslim Weddings: Keeping Up with the Times

Customs and traditions change over time. Asrina Tanuri and Nadya Suradi trace how Malay-Muslim weddings in Singapore have evolved since the 1950s.

The insistent rhythms of the handheld kompang drum heralding the groom’s arrival, the resplendent bride glowing with happiness and the upbeat music accompanying the feasting throngs: there is nothing quite like a traditional Malay wedding to inject colour and life into the humdrum rhythms of a public housing estate in Singapore. On their wedding day, the newlyweds are treated like royalty and accorded the term raja sehari (“King and Queen for a day”).1

As traditional as it appears though, Malay wedding customs in Singapore have changed considerably in the last few decades. These changes are part of a larger phenomenon of Malay customs evolving in response to modernity and current trends. As well-known writer and Malay culture expert Muhammad Ariff Ahmad noted in 1999:

“Perpindahan dari sistem kehidupan kampung ke sistem kehidupan bandar dan hidup berbaur dengan masyarakat yang bukan seadat resam itu merupakan dua faktor yang secara tidak langsung dan beransur-ansur telah mendorong perubahsuaian beberapa adat Melayu lama menjadi adat baru yang sesuai diamalkan di Singapura, sekarang.”2

(Translation: The move from living in a kampong to an urban lifestyle and living in a multicultural community are two factors that have indirectly and gradually led to the modification of some old Malay customs into new ones that are currently practised in Singapore today.)

Urbanisation – which resettled communities living in kampongs into high-rise flats in public housing estates – was certainly one of the main reasons behind the changes. The spirit of gotong royong, or communal help, that was marshalled at Malay weddings in kampongs – along with traditional ceremonies associated with the walimah, or wedding feast, and its elaborate preparations – became eroded as more and more kampong folk moved into high-rise flats.

Economic growth and increased modernisation since Singapore’s independence have also impacted traditional Malay weddings. Growing affluence, popular culture and a desire by young people to be seen as more “modern” have driven some of the changes as well, nudging couples towards more streamlined and pared-down customs, and introducing so-called “modern” flourishes.

In addition, a growing awareness of what constitutes Islamic practice has resulted in certain customs and rituals being abandoned because these have been deemed as non-Islamic.

Changing Times

Malay weddings incorporate both Islamic practices as well as customs that are specific to Malay culture.3 In Singapore today, the core ceremonies are the nikah (the solemnisation), walimah (the communal wedding feast), bersanding (sitting-in-state during the walimah) and bertandang (the ceremony to welcome the bride/in-laws). All of these have changed over the last 50 or 60 years, both in ways large and small.

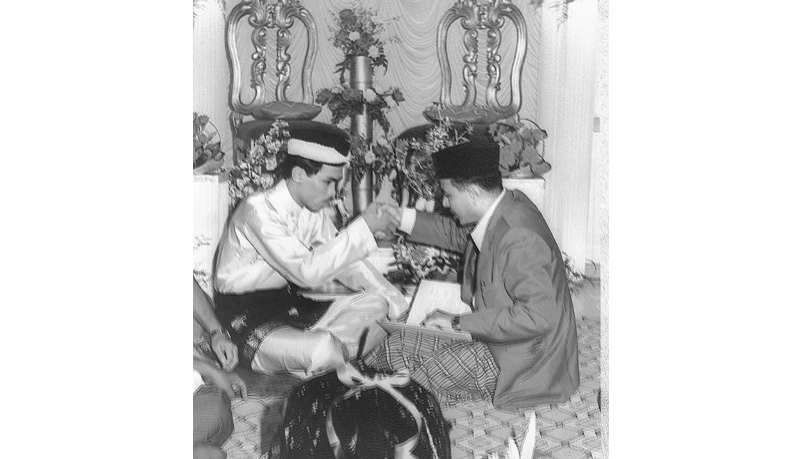

Among these ceremonies, nikah is the only religious obligation stipulated by Islam. Traditionally, it takes place the day before walimah and bersanding. An intimate affair attended by close family members and friends, the solemnisation ceremony is held at the bride’s residence or at a reception venue. A religious official, known as the tok kadi, officiates and oversees the proceedings and also issues the marriage certificate.4

During this ceremony, it is customary for both parties to exchange dulang hantaran (trays of gifts), with the groom presenting to his bride a pre-agreed duit hantaran (cash gift) and the mandatory mas kahwin (literally “wedding gold”).5 Mas kahwin, also known as mahar, is an obligatory gift from the groom to his bride to signify the beginning of a husband’s responsibility towards his wife.6

In the past, it was common for the payment of mas kahwin to be presented to the bride after the wedding. In an oral history interview, trainee teacher Mohd Amin bin Abdul Wahab, who got married in 1941, recalled: “Belanja kahwin saya cuma seratus lima puluh ringgit. Mas kahwin [saya] dua puluh dua ringgit setengah, hutang” (I only spent $150 [in total] on my wedding. My mas kahwin was a deferred payment of $22.50).7

Today, grooms are expected to give at least $100 for the mas kahwin, with the full amount given upfront. However, grooms can also opt to give gold or jewellery in lieu of cash.

The duit hantaran, also known as hantaran belanja, is a customary gift from the groom to the bride’s family to cover the expenses for the wedding day. In the late 1960s, the amount ranged between $500 and $1,000, with the money handed over before the nikah ceremony. From the 1980s, however, the duit hantaran began to take centre stage during nikah.

Grooms today are expected to fork out between $8,000 and $20,000, depending on how wealthy they are. The figure is sometimes tagged to the bride’s educational background; the better educated the bride, the higher the amount expected. (The amount is usually negotiated beforehand.)8

The nikah ceremony is also an occasion for the groom to present gifts to the bride. In the past, these gifts were typically a set of clothes for the bride and a selection of Malay cakes and desserts. These gifts were creatively packaged, wrapped and displayed on trays decorated with flowers and ribbons. Some gifts even featured fabric intricately folded into swans or flowers, and individually wrapped chocolates made into structures such as floral arrangements, houses and baskets. These days, brides and grooms may exchange gifts such as jewellery, watches, shoes, wallets, handbags, cosmetics and electronic gadgets, in addition to cakes and chocolates. Some couples even present each other with expensive items like motorcycles and cars.9

Walimah Ceremony

The Malay wedding reaches its peak during the walimah and bersanding ceremonies, the wedding feast and the sitting-in-state respectively. The wedding feast, which typically takes place the day after the nikah, usually starts at 11 am and ends at 5 pm. It is an informal gathering of family, relatives and friends, with guests numbering in the hundreds and sometimes thousands. They are served a feast of either nasi minyak (ghee rice) or nasi biryani (spiced long-grain rice), accompanied by various dishes.10 Up to the 1950s, when most Malays largely lived in kampongs, the walimah and bersanding ceremonies would be held under tents in the village.

These events were typically communal events involving the entire kampong in the spirit of gotong-royong. It was customary to round up family members and enlist the entire village to help out with both the wedding preparations as well as the festivities leading up to the wedding day.

Physically demanding tasks such as carpentry and house painting were handled by men, while women helped to decorate the bridal dais with palm and banana leaves and paper flowers, as well as cook for the volunteers. The wedding feast would also be painstakingly prepared and cooked by family, friends and neighbours, with some even contributing ingredients for the feast.11

Abu Talib Bin Ally, who lived in Kampong Glam in the 1920s, recalled how friends and relatives would come over days before the wedding to help out at the bride’s and groom’s homes:

“Tiga hari, empat hari, nanti anak buah semua ramai-ramai tinggal sana. Masak, makan. Kalau kita masak-masak ni semua itu jam tak ada contract. Sendiri mesti mahu masak… [M]asak sendirilah, gotong-royong…”12

(Translation: Three or four days [before the wedding], friends and relatives would all gather at the [bride’s and groom’s] houses. To cook, to eat. Previously, you would not be able to hire a caterer so you had to cook [the food] yourself… Cook it yourself in the spirit of gotong royong.)

The food would be served in the traditional style called makan berhidang, in which each table receives portions enough for three to four people. Guests would be served by the kendarat (waitstaff) who deliver the food and drinks to the tables as well as water for washing hands. Family members and friends would often volunteer to serve the guests.

The communal aspect of the wedding feast is no longer the case today as prominent writer Aliman Bin Hassan notes:

“Biasanya kalau dalam masyarakat kampung… bila mereka telah tinggal satu kampung, mereka bukan lagi menganggap mereka itu bersahabat, tapi bersaudara… Sebab itu bila ada majlis kerja kahwin, kita tidak risau tentang kendarat, tentang orang yang nak kopek bawang, nak potong lada… masak dan sebagainya… Tidak seperti sekarang ini. Sebab masing-masing sibuk dengan tugas. Masing-masing sudah mempunyai pelajaran. Jadi mereka tidak cukup masa untuk memberi sumbangan tenaga.”13

(Translation: Usually, in the village community… when [villagers] live together, they no longer think they are just friends, but they consider themselves as family… Hence, when there was a wedding, we would not worry about who would be helping to serve the guests, who would be peeling onions, cutting chillies… doing the cooking and so on… Today the situation has changed. Everyone is busy with work and studies. They do not have time to contribute to weddings.)

Kampong life ended as the government began resettling people from rural areas into public housing estates from the 1960s. As people no longer lived in the kampong, the wedding feast was instead held in the ground-floor void decks of flats. More significantly though, the move out of the communal kampong environment to the anonymity of a large public housing estate also led to the loss of the gotong royong spirit.14

As a result, the majority of Malay families today engage caterers for the wedding reception and outsource the kendarat roles. While the staple menu of nasi minyak or nasi biryani and the accompanying dishes largely remain, food is no longer served to guests at the table; instead, a buffet service is more likely provided (before the pandemic restrictions at least).

From the early 2000s, couples began engaging the services of wedding planners and gravitating towards grander, themed weddings. Depending on the theme, the wedding venue might be transformed into a lush English garden, a rustic kampong, a scene from a fairy tale or a whimsical wonderland. Guests are strongly encouraged to dress up according to the theme. In addition to the buffet spread, guests may be treated to live food stations, dessert tables and self-service photography booths.15

In recent years, one-stop wedding services that provide the wedding venue itself, along with decorations, food and door gifts, have been gaining popularity. And instead of void decks, many couples choose to hold their wedding receptions at outdoor locations such as gardens and beaches, community clubs, country clubs, restaurants and hotel ballrooms. Some may even have an additional dinner reception held in the evening just for a select group of friends and colleagues.16

The types of entertainment for wedding guests have also changed. Until the 1980s, it was common to have performances such as kuda kepang (a Javanese dance in which performers straddle wooden hobby horses and enter a trance-like state), silat martial arts demonstrations, and traditional orchestras and bands playing live music of various genres. The latter would include popular and traditional Malay music such as zapin, masri, inang, joget and dondang sayang, as well as Hindi and English songs. There were even joget lambak (traditional mass dancing) sessions. These days, however, the scaled-down entertainment usually consists of just deejays spinning music.17

Bersanding Ceremony

The sound of the kompang, sometimes referred to as rebana, and a troupe singing along to the beating drums, signals the arrival of the groom and his entourage. Flanked by his pengapit (groomsmen), the groom begins a processional march known as berarak.

Accompanying him are two men carrying the bunga manggar (palm blossoms made from tinsel paper). The bride awaits on the bridal dais, her face shielded by a fan held by the mak andam (the makeup artist-cum-lady-in-waiting).18

To reach the bride, the groom must first overcome various hadang (roadblocks or obstacles). During the first hadang, witty pantuns (Malay poems) are exchanged between the pengapit and the bride’s wedding party. The groom must also pay what is known as the duit pagar, or “gate fee”. After the groom passes the tests, he is allowed to be seated in front of the bridal dais and a silat pengantin (Malay martial arts display) performed for him.19

The final hadang takes place at the bridal dais itself, this time between the groom and the mak andam. He pays her the duit kipas (fan money); once satisfied, she reveals the bride and the groom finally takes his seat on the dais beside the bride.20

Traditionally, the groom’s older relatives were roped in to be the groomsmen and expected to partake in the exchange of pantuns. These days however, the pengapit role is assumed by friends. It has also become customary in Malay weddings for the groom and his groomsmen to perform a series of tasks, such as singing and dancing, before he is allowed to meet his bride, possibly borrowed from a similar Chinese tradition.

Pantuns are also rarely exchanged today. Instead, to appease the bride’s side and avoid having to perform additional tasks, the groom would offer money to the bride’s party so that he would be allowed to take his place by his bride on the dais.

Once the groom is seated on the dais, family members and guests take turns to go up and congratulate the couple and to have their photos taken with them. The bersanding ceremony ends with the bride and groom having their first meal together as husband and wife, known as the makan berdamai. In the past, the couple would retreat to the bridal room to have their meal, accompanied by their pengapit. Today, the bride and groom are seated at a special dining table set up near the dais so that they can mingle and interact with their guests.21

The last leg of the ceremony is known as bertandang and takes place at the groom’s residence. In the past, this would be held a week after the wedding feast. Bertandang, also known as majlis sambut menantu (welcoming the bride/in-laws), is when the groom brings his new bride back to his kampong to be introduced to the rest of his family members and other village residents. A second and smaller bersanding ceremony would be conducted at the groom’s residence.22

Today, however, the bertandang ceremony usually takes place on the same day as walimah and bersanding. After lunch, a wardrobe change and photos with guests, the newlyweds depart for the groom’s home.23

Back when Malays largely lived in kampongs, weddings typically spanned a week, from the nikah to the bertandang ceremonies. These days, couples are more likely to prioritise convenience, simplicity and practicality over tradition. Many choose to have the nikah, walimah and bersanding ceremonies on the same day instead of having the solemnisation performed the day before the wedding feast. Some couples even forego the bertandang ceremony altogether. As Malay dance pioneer and Cultural Medallion recipient Som Said has noted:

“Kalau kita nak cakap pasal masa kini, yang tinggal cuma pernikahan dan bersanding. Ringkas kerana mengikut tuntutan masa… Banyak yang dah takde. Banyak yang dihilangkan, bukan hanya dalam majlisnya tapi dalam peradaban, peralatan, persiapan semua… yang tak perlu tu sudah dikikis.”24

(Translation: If we want to talk about the present, what is left is just the nikah and bersanding ceremonies. Simple and practical due to time constraints… A lot have been done away with. Many aspects of the Malay traditions have been removed, not only in the ceremony but also in traditions, equipment, preparation… those that are not necessary are no longer practised.)

Berinai Ceremonies

A tradition that used to be a major part of Malay weddings, but is rarely observed in Singapore today, is the berinai comprising three ceremonies: berinai curi (curi means “steal” in Malay), berinai kechil (small henna ceremony) and berinai besar (big henna ceremony). The traditional tepung tawar (blessing ritual) was the central element in all three berinai ceremonies.

The berinai curi and berinai kechil ceremonies would take place before the solemnisation.25 Berinai curi was organised for the bride and involved her female relatives and close female friends. During this ceremony, the bridal party would perform the tepung tawar for the bride before applying henna on her hands and feet. It is traditionally held without the knowledge and consent of the groom’s side, hence the name berinai curi, and usually takes place two days before the nikah, in the evening.26

The berinai kechil ceremony is held the next evening, involving both the bride and groom. The couple undergo tepung tawar separately, with the groom going first, followed by the bride.27 The berinai besar ceremony, on the other hand, would be held right after the solemnisation, usually at the bride’s home. It comprised the tepung tawar and included a photography session, during which the bride might have up to 20 changes of outfits.28

However, all three berinai ceremonies are rarely conducted today, partly due to the costs and time involved. The berinai curi and the berinai kecil fell out of favour first; by the 1980s, only the berinai besar was commonly performed.29 This last ceremony, too, eventually disappeared by around the early 2000s.30

Stricter Adherence to Islam

One of the key drivers of change has been a greater understanding and awareness of Islamic obligations. Rituals that are deemed haram, or forbidden under Islam, have been jettisoned. An example of this is the almost complete disappearance of the tepung tawar blessing ceremony because of its purported Hindu origins.

During tepung tawar, the person officiating the blessing first sprinkles rose water and yellow rice on the newlyweds and then dots henna as well as rice flour mixed with water on their palms. A groomsman or bridesmaid wipes away the henna, while the person offering the blessing ends the ceremony by lightly touching an egg to the noses of the couple. During the berinai besar ceremony, the officiator would be presented with a flower from the pulut pahar (a floral bouquet made of yellow glutinous rice, flowers and hard boiled eggs) as a token of appreciation.31

Today, the tepung tawar ritual is rarely practised. If it does take place at all, it happens during the bersanding ceremony and is officiated by the elders in attendance, including the parents of the bride and groom.

The potong andam (a beautifying ritual ceremony involving the bride-to-be and the mak andam), is another ritual that is no longer carried out today because it is perceived as non-Islamic. The purpose of this ceremony is to beautify the bride by cutting or shaving the fine hairs on her face and body.

During this process, the mak andam would recite mantras while removing the hair. A second part of the ceremony involves the mak andam observing how the cut hairs fall and using that to determine if the bride is a virgin. Due to the spiritual but non-Islamic nature of this ceremony, it is no longer conducted.32

The aforementioned Javanese kuda kepang dance, which used to be a popular form of entertainment at weddings, also fell out of favour for the same reason. In Singapore, the dance was commonly performed at Malay weddings in the 1970s and early 80s. Dancers would enter into a trance and perform feats like peeling coconut husks using their teeth, chewing or eating glass, and drinking buckets of water. However, in 1979, Majlis Agama Islam Singapura (Islamic Religious Council of Singapore) advised that the trance elements of kuda kepang contravened the tenets of Islam and urged Muslims to avoid such performances.33 As a result, the practice has died out.

Not Just Singapore

Many of the changes that Malay wedding customs have undergone in Singapore are replicated in cities like Kuala Lumpur. The makeshift tents in front of houses for the wedding feast (itself an adaptation from the communal space in a kampong) and the gotong royong spirit in preparing for the wedding ceremony and reception have given way to catered events at banquet halls or hotel ballrooms. Elaborate and time-consuming ceremonies have also been simplified. And, like bridal couples in Singapore, Malaysian couples are also opting for themed weddings with wedding planners helping to organise their big do, although the tepung tawar ritual is still practised in Malaysia.34

Inevitably, customs and traditions will evolve in response to social and economic changes. As new norms and new expectations develop, Malay wedding customs will also evolve in tandem.

BUNGA TELUR

Wedding favours are known as berkat kahwin or berkat pengantin. Traditionally, guests at Malay weddings are given a bunga telur (literally a “flower egg”) as a token of appreciation. A bunga telur comprises a red hard boiled egg resting on top of a bed of pulut kunyit (yellow glutinous rice) in a glass decorated with flowers, hence its name.35

A bunga telur comprises a red hard boiled egg resting on top of a bed of pulut kunyit (yellow glutinous rice) in a glass decorated with flowers. Courtesy of Asrina Tanuri.

A bunga telur comprises a red hard boiled egg resting on top of a bed of pulut kunyit (yellow glutinous rice) in a glass decorated with flowers. Courtesy of Asrina Tanuri.

Each part of the bunga telur has a special meaning. The egg symbolises fertility and prosperity. The yellow glutinous rice represents harmony, honesty and royalty – referring to the bride and groom, who are regarded as royals for the day – while the flower signifies love in their marriage.36

In the past, the making of the bunga telur was an opportunity for family members, neighbours and friends to lend a helping hand with the various tasks involved, such as boiling the eggs, steaming the glutinous rice, colouring the eggs and decorating with the flowers.37

These days, however, many couples choose to go for modern, hassle-free wedding favours. Cakes and chocolates, and items such as hand towels, plates and mugs, have replaced the bunga telur.38

BRIDAL OUTFITS AND THE MAK ANDAM

The world of fashion is one of constant change and wedding outfits are no exception. Between the 1950s and 1990s, popular outfit choices for the bersanding ceremony were the traditional baju kurung or kebaya for women and the baju Melayu for men, made from fabrics such as traditional songket,39 brocade or velvet. These outfits were intricately embroidered and embellished with sequins and beadings. An elaborate sanggul (metal headdress) for the bride and a tanjak (headgear) and keris (dagger) for the groom completed the attire.40

Although many brides today still opt for the classic songket fabric for their attire, the baju kurung or kebaya styles in which they are sewn into have been given a more contemporary spin to keep pace with current sartorial trends. Some brides also choose to commission bespoke one-of-a-kind songket outfits instead of renting from bridal houses. It is also common for brides to wear outfits inspired by the Western wedding gowns using fabrics such as chiffon, satin and lace, while grooms don formal Western suits.41

Another change has been to the role of the mak andam, who has one of the more important jobs during a Malay wedding. In addition to doing the bridal makeup, the mak andam is the de facto protocol guide of a traditional Malay wedding. On the big day, it is the job of the mak andam to guide the bride and groom during the many ceremonies.42

Today, however, the mak andam has been relegated to a less important role. In a 2017 television interview, Malay dance pioneer and Cultural Medallion recipient Som Said said:

“… kalau you dah istilahnya dah jadi mak andam, you bukan hanya menyiapkan pengantin tu sahaja. Peradaban, the protocol, bila nak salam, bila nak ini [itu], semua sudah harus tahu. Jadi [it] is not that dulu-dulu orang tanya, you nak kahwin eh, Mak andamnya siapa? Oh, straightaway people tahu, oh, ini tatasusila nya bagus. Tapi sekarang tidak. Who is the mak andam? Oh it is about the dressing, it is about the look?”43

(Translation: … if you are a mak andam, your duties will extend beyond just dolling up the bride. You will have to know the various cultural traditions, protocols and rites. Previously, when people ask which mak andam you picked, they would go oh, this mak andam has very good mannerisms and adherence to traditions. Whereas nowadays, when people ask who is the mak andam, they are comparing how stylish the makeup and outfits are.)

Nadya Suradi is an Assistant Manager with Programmes and Exhibitions. She curates programmes to introduce younger people to the collections of the National Library and National Archives.

Nadya Suradi is an Assistant Manager with Programmes and Exhibitions. She curates programmes to introduce younger people to the collections of the National Library and National Archives.

Asrina Tanuri is a Manager (Research) with the National Library, Singapore, where she provides information services to government agencies. Her research areas include community safety and security, and adult learning.

Asrina Tanuri is a Manager (Research) with the National Library, Singapore, where she provides information services to government agencies. Her research areas include community safety and security, and adult learning.

NOTES

-

A. Kadir Pandi. (1986, March 26). Kain songket lambang budaya kita. The Straits Times, p. 5; Zakaria Buang. (1982, November 29). Pakaian pengantin tradisional. Berita Minggu, p. 3. Retrieved from NewspaperSG; Hanisa Hasan. (2016, November 15). A study on the development of baju kurung design in the context of cultural changes in modern Malaysia. Wacana Seni Journal of Arts Discourse, 15, 63–94. Retrieved from ResearchGate website. ↩

-

Muhammad Ariff Ahmad. (1999). Adat Melayu Singapura. Sekata. 1 (11), 1–8. Retrieved from National Institute of Education website. ↩

-

Amran Kasimin. (2002). Perkahwinan Melayu (pp. 84–85). Kuala Lumpur: Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka. (Call no.: Malay R q392.509595 AMR-[CUS]); Hidayah Amin. (2014). Malay weddings don’t cost $50 and other facts about Malay culture (p. 97). Singapore: Helang Books. (Call no.: RSING 305.8992805957 HID) ↩

-

Hidayah Amin, 2014, pp. 95–97. ↩

-

Muhammad Ariff Ahmad. (2007). Nilam: Nilai Melayu menurut adat (pp. 278–279). Singapore: Majlis Pusat Pertubuhan-Pertubuhan Budaya Melayu Singapura. (Call no.: Malay RSING 305.89928 MUH); Hidayah Amin, 2014, pp. 95–97. ↩

-

Registry of Muslim Marriages. (2019, May 10). Maskahwin & marriage expenses. Retrieved from Registry of Muslim Marriages website. ↩

-

Ruzita Zaki. (Interviewer). (1995, February 7). Oral history interview with Mohd Amin bin Abdul Wahab (Haji) [MP3 recording no. 001597/44/7]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

Azahar Mohamed. (1999, May 23). Wang hantaran tinggi? Itu cabaran lelaki pertingkat diri. Berita Minggu, p. 8; Perihal mas kahwin dan wang hantaran. (2015, August 11). Berita Harian, p. 7. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Muhammad Ariff Ahmad, 2007, pp. 278–279; Zaharian Osman. (2009, April 11). Barang hantaran kian canggih. Berita Harian, p. 22; Farid Hamzah. (2010, January 4). Dariku untukmu, sayang: Hantaran. Berita Harian, p. 8; Zawiyah Salleh. (2009, March 18). Gubah hantaran pengantin. Berita Harian, p. 9. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Hidayah Amin, 2014, pp. 97–98. ↩

-

Muhammad Ariff Ahmad, 2007, pp. 274–275; Hadijah Rahmat. (2005). Kilat senja: Sejarah sosial dan budaya kampung-kampung di Singapura (pp. 243–244). Singapore: HS Yang Publishing. (Call no.: Malay RSING 959.57 HAD) ↩

-

Encik Abdul Ghani bin Hamid (Interviewer). (1991, January 16). Oral history interview with Abu Talib bin Ally [MP3 recording no. 001216/11/3, p. 63]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

Mohd Yussoff Ahmad. (Interviewer). (1987, March 12). Oral history interview with Aliman bin Hassan (Haji) [MP3 recording no. 000797/11/2]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

Haron Abdul Rahman. (1986, February 12). The big day and its rites. The Straits Times, p. 20; Lebih meriah kalau adakan majlis di tempat sendiri. (1986, March 30). Berita Harian, p. 11. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Spykerman, K. (2012, January 15). My big fat void deck wedding. The Straits Times, p. 2; Shahida Sarhid. (2012, September 30). Kambing barbeku, susyi antara hidangan. Berita Harian, p. 6. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Nur ‘Adilah Mahbob. (2013, May 24). Taman jadi laman popular majlis kahwin. Berita Harian, p. 14; Salma Semono. (2007, July 28). Sajian untuk jemputan. Berita Harian, p. 27. Retrieved from NewspaperSG; Norhaiza Hashim & Shahida Sarhid. (2019, October 6). Khidmat semua di ‘bawah satu bumbung’ kian jadi pilihan mempelai. Berita Minggu. Retrieved from Factiva via NLB’s eResources website. ↩

-

Azman Siraj. (1990, October 24). Khidmat DJ kian popular dalam majlis perkahwinan. Berita Harian, p. 6; Ismail Pantek. (2010, June 14). Semua ‘turun padang’ rewang. Berita Harian, p. 9; Kamali Hudi. (2002, August 17). Lagu pengantin citra warisan. Berita Harian, p. 22. Retrieved from NewspaperSG; Hadijah Rahmat, 2005, p. 244. ↩

-

Hadijah Rahmat, 2005, p. 241; Muhammad Ariff Ahmad. (1988, April 7). The grand finale in the Malay wedding. The Straits Times, p. 6. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Silat pengantin is a ceremonial Malay martial arts performance to honour and give strength to the groom and to welcome the newlyweds. Compared to pencak silat (Malay martial arts), silat pengantin uses gentler hand movements, which are still executed in firm and strong strokes to convey respect and honour to the newlyweds. The silat pengantin is performed in rhythm with accompanying music from the kompang troupe. The performance ends with a handshake between the groom and the silat performer. See Pendekar Temasek. (2019). Silat pengantin (pp. 24–40). Singapore: Pustaka Nasional Pte Ltd. (Call no.: Malay RSING 796.81509595 PEN); The Straits Times, 7 Apr 1988, p. 6; Koh, J., & Ho, S. (2009). Culture and customs of Singapore and Malaysia (p. 119). Santa Barbara, California: Greenwood Press. (Call no.: YP R305.80095957 KOH) ↩

-

The Straits Times, 7 Apr 1988, p. 6; Muhammad Ariff Ahmad. (1993). Bicara tentang adat dan tradisi (pp. 44–46). Singapore: Pustaka Nasional. (Call no.: Malay RSING 306.08999205957 MUH) ↩

-

Muhammad Ariff Ahmad, 2007, p. 282. ↩

-

Muhammad Ariff Ahmad, 2007, p. 282; Muhammad Ariff Ahmad, 1993, pp. 45–46; The Straits Times, 7 Apr 1988, p. 6. ↩

-

Muhammad Ariff Ahmad, 1993, pp. 45–46; Hidayah Amin, 2014, p. 107. ↩

-

Mediacorp News Group. (2017, October 18). DETIK Episod 13: Pasangan muda ini memilih untuk terus memartabatkan adat istiadat perkahwinan Melayu. Retrieved from Berita Mediacorp website. ↩

-

Muhammad Ariff Ahmad, 2007, pp. 271, 275–276. ↩

-

Muhammad Ariff Ahmad, 2007, p. 275. ↩

-

Muhammad Ariff Ahmad, 1993, p. 40. ↩

-

Muhammad Ariff Ahmad, 1993, p. 40. ↩

-

Adat perkahwinan banyak berubah. (1983, September 1). The Straits Times, p. 4; Dua ‘pencurian’ dalam berinai curi. (1988, March 24). The Straits Times, p. 5. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Muhammad Ariff Ahmad, 2007, p. 248; Berinai di pelamin: Adat perkahwinan orang Melayu. (2006, March 5). Berita Harian, p. 11. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The pulut pahar is a floral bouquet comprising a base of pulut kuning (yellow glutinous rice) adorned with the stalks of handmade flowers and hard boiled eggs. When the pulut kuning is absent, the arrangement is known as bunga telur. The pulut pahar, which is distributed to those attending the tepung tawar ceremony, is not to be confused with the bunga telur given to all guests at the wedding reception. In the past, half of the bunga pahar or bunga telur would be given to the mak andam (makeup artist-cum-lady-in-waiting). See Muhammad Ariff Ahmad, 2007, pp. 275–276. ↩

-

Muhammad Ariff Ahmad, 2007, pp. 276–277; Amran Kasimin. (2002). Perkahwinan Melayu (pp. 49–52). Kuala Lumpur: Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka. (Call no.: R q392.509595 AMR-[CUS]) ↩

-

Advisory on kuda kepang performances. (2019, July 25). Office of the Mufti. Retrieved from Majlis Ugama Islam Singapura website; ‘Kuda kepang’ against Islam: Muis. (1979, June 14). The Straits Times, p. 12. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Fatimah Abdullah. (2009). Dari halaman rumah ke Dewan Merak Kayangan: Upacara perkahwinan Melayu bandar. SARI: Jurnal Alam dan Tamadun Melayu, 27, 97–107. Retrieved from UKM Journal Article Repository website; Mohd Khairuddin Mohd Sallehuddin & Mohamad Fauzi Sukimi. (2016). Impian dan realiti majlis perkahwinan orang Melayu masakini: Kajian kes di pinggir bandar Kuala Lumpur. Geografia: Malaysian Journal of Society and Space, 12 (7), 1–12. Retrieved from UKM Journal Article Repository website. ↩

-

A. Hamid Besih. (1996, September 28). Pengertian di sebalik ‘bunga telur’ hampir lebur. Berita Harian, p. 7. Retrieved NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Berita Harian, 28 Sep 1996; p. 7; Hanim Mohd Saleh. (2004, February 15). Bunga telur semakin dipinggir. Berita Harian, p. 11. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Berita Harian, 15 Feb 2004, p. 11; Hadijah Rahmat, 2005, p. 241; Muhammad Ariff Ahmad, 2007, p. 275. ↩

-

Berita Harian, 15 Feb 2004, p. 11; Muhammad Ariff Ahmad. (1999). Adat Melayu Singapura. Sekata. 1 (11), 1–8. Retrieved from National Institute of Education website. ↩

-

Songket is a cotton or silk fabric interwoven with gold or silver threads. This traditional Malay handwoven fabric comes in wide variety of designs and patterns. The cost of a songket outfit can go up to the thousands, depending on the quality of fabric, density of threads and intricacy of design and colours. Malays typically don songket during festive and formal occasions such as weddings and Hari Raya. See Kong, L. (1989, January 16). Songket: Symbol of a rich tradition. The Straits Times, p. 6. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Zakaria Buang. (1981, November 29). Pakaian pengantin tradisional. Berita Minggu, p. 3; Wan Jumaiah Mohd Jubri. (1996, September 28). ‘Biru, birulah… coklat, coklatlah… pengantin dulu memang tak kisah’. Berita Harian, p. 10. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Pakaian tradisional terus jadi pilihan. (1991, September 27). Berita Harian, p. 12; Ismawati Ismail. (2012, January 21). Majlis unik ‘lain daripada yang lain’. Berita Harian, p. 17; Fesyen selebriti jadi trend terbaru pengantin. (2013, December 29). Berita Harian, p. 19. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Umur mak andam semakin muda. (1987, July 21). The Straits Times, p. 6. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Mediacorp News Group (2017, October 18). DETIK Episod 13: Pasangan muda ini memilih untuk terus memartabatkan adat istiadat perkahwinan Melayu. Retrieved from Berita Mediacorp website. ↩