The Evolution of Straits-born Cuisine

Lee Geok Boi looks at what makes Peranakan cuisine unique and delves into old cookbooks to see how Straits-born cuisine came to be.

Bakwan kepiting. Babi pongteh. Ayam buah keluak. Many Singaporeans would describe these dishes as classic Peranakan or Straits Chinese dishes. However, the Malay word “peranakan” means “local born”, so perhaps a more accurate term for this cuisine is not so much “Straits Chinese” but “Straits-born”.

The Straits, in this case, refers not only to the territories of the former Straits Settlements, namely Singapore, Melaka and Penang, but also the islands that make up the Indonesian archipelago – an area that historians refer to as Island Southeast Asia. Through centuries of trade and colonisation, the people of Island Southeast Asia melded ancient culinary traditions with colonial culinary cultures and introduced ingredients that gave rise to several hybrid cuisines characteristic of the Straits-born communities – Eurasian (mainly of Portuguese, Dutch and English heritage),1 Chetti Melaka (or Chitty Melaka)2 as well as Penang, Melaka and Indonesian Chinese.

In Straits-born kitchens, housewives and servants whipped up meals that were rooted in the geography, history and traditional ingredients of Island Southeast Asia. These resulted in a fusion cuisine that we enjoy and are familiar with today.

The Rich Flavours of Straits-born Cuisine

What makes a cuisine Straits-born? Well, it would feature dishes that are an amalgamation of Indian, Chinese and European influences infused with traditional Malay-Indonesian and Southeast Asian cooking. The latter two cuisines evolved from what indigenous cooks first found in the wild and began cultivating in kitchen gardens, along with ingredients sourced from village markets.

Numerous aromatics such as lemongrass (Cymbopogon) or serai in Malay, and galangal (Alpinia galanga) or greater galangal, also known as lengkuas or blue ginger, are native to Southeast Asia. Several types of ginger such as the common ginger (Zingiber officinale) can be found across Asia – from South Asia through Southeast Asia to East Asia. Locally available plants that yield fragrant leaves used in Straits cooking include those from the kaffir lime or limau perut in Malay (Citrus hystrix), also known as the makrut lime, and the pandan (Pandanus amaryllifolius) or screwpine.

Certain local flowers are also used in Southeast Asian cooking. The blue pea flower or butterfly pea flower (Clitoria ternatea), known in Malay as bunga telang, is favoured as a natural food colouring in otherwise boring, white glutinous rice desserts while the superb fragrance of the torch ginger bud (Etlingera elatior), or bunga kantan, adds flavour to salads and curries.

As its scientific name suggests, the blue pea flower originally came from Ternate, one of the fabled Spice Islands of the Moluccas (now Maluku Islands). The Spice Islands are the original source of the world’s nutmeg (Myristica fragrans), candlenut or buah keras (Aleurites moluccana), and clove (Syzygium aromaticum).

In addition to aromatics, various useful plants that yield valuable cooking ingredients can also be found in this region. They include palms such as the coconut palm (Cocos nucifera) and sago palm (Metroxylon sagu).

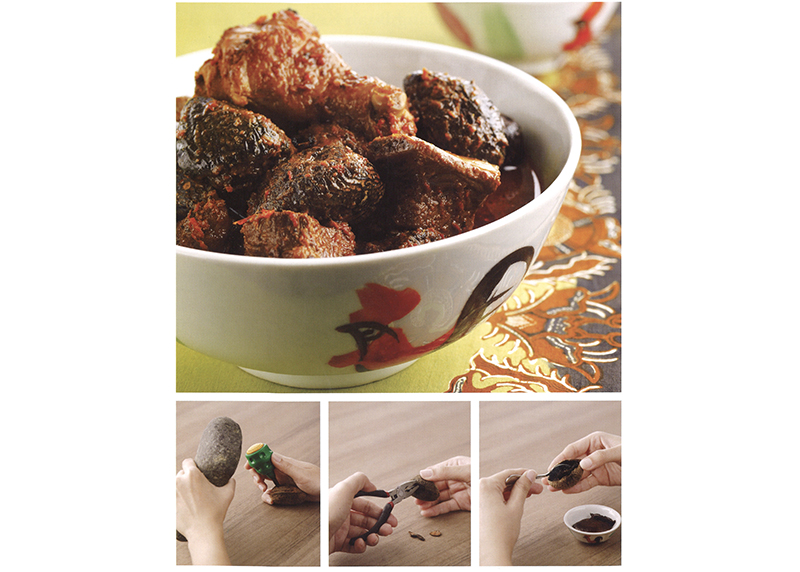

East Java is the main source of buah keluak, the hard nut of the kepayang (Pangium edule), a tropical tree native to Indonesia, Malaysia and New Guinea. As hydrogen cyanide, a poison, is found in all parts of the tree, the nuts have to undergo a complicated process to neutralise the poison before they can be sold. Aficionados of buah keluak then go through another process to thoroughly clean and shell the nuts before cooking them with chicken or pork in this unusual-looking dish.

Global trade and the movement of traders added yet more ingredients to an already well-endowed Southeast Asian culinary tradition.3 Pepper (Piper nigrum), originally native to India, has been cultivated in Java and Sumatra since 200 BCE. Turmeric (Curcuma longa) and cardamom (Elettaria cardamomum), two members of the ginger family, are native to India, as are tamarind (Tamarindus indica), or asam, and the mango (Mangifera indica).

The Indian traders who introduced Buddhism and Hinduism to Southeast Asia also brought with them seed spices that they had acquired through trade further westwards: coriander (Coriandrum sativum) from the southern Mediterranean, cumin (Cuminum cyminum) from West Asia, fennel (Foeniculum vulgare) from southern Europe and West Asia, and fenugreek (Trigonella foenum-graecum) from southern Europe and West Asia. These spices became essentials in the spice mixes used in Indian and Straits-born cuisines.

There is also Chinese influence in Southeast Asian cooking. Chinese traders, notably Hokkiens from Fujian province, began arriving in Southeast Asia as early as the 10th century. The Hokkiens describe Fujian as “eight parts mountains, one part water and one-part farmland”.4 They naturally turned to the sea to improve their economic lot and formed trading hubs in Southeast Asian port cities along the maritime Silk Road, stretching from southern China past the waters of Island Southeast Asia westwards to South and West Asia.

One such hub in 15th-century Melaka evolved into the Baba Malay-speaking Straits Chinese (Baba Malay being a creole language combining Malay and Hokkien) as well as giving rise to the Chetti Melaka. The Straits Chinese hub in Penang, which was founded as a British trading port in 1786, remained primarily Hokkien-speaking. These accidental settlers brought with them traditional Chinese condiments such as soya sauce (made from fermented soya beans) and other soya products. Originally from Southeast Asia, soya beans were domesticated in China as early as 1100 BCE.5

It is believed that the Chinese introduced fermentation technology to the region. However, the inhabitants of ancient Island Southeast Asia probably already knew much about fermented foods. These include belacan (fermented krill paste) and chinchalok (fermented krill), traditional foods that are popular regionally. Ancient Javanese records list some of the food and drinks once consumed in the 10th century such as fermented rice (tapeh) and fermented drinks like palm wine or toddy.6

The sugarcane (Saccharum officinarum) made its way to Indonesia and India perhaps as early as 8000 BCE. But what we call sugar today only became common from the 16th century onwards after sugar plantations using African slave labour in the West Indies produced sugar in quantities large enough to meet popular demand in Europe.7 Southeast Asian desserts were, and still are, sweetened with palm sugar, of which gula melaka (known as gula jawa in Indonesia) is just one kind. Different kinds of palms yield sweeteners in various hues and with different fragrances.

The arrival of the Portuguese in the 16th century brought about one of the biggest changes to the flavour profile of South Asian and Southeast Asian cooking. This was the introduction of the chilli (Capsicum frutescens) to Goa and Melaka following their colonisation by the Portuguese in 1510 and 1511 respectively. Chilli plants were originally native to Mexico and Central America and the word “chilli” means “hot pepper” in Nahuatl, the language of the Aztecs.

The subsequent arrival of the Dutch and British brought wheat flour and butter, without which Straits-born classics such as sugee cake and kueh lapis8 (also known as spekkoek, meaning “bacon cake” in Dutch) would not be possible. Traditional Southeast Asian kueh (or kuih; bite-sized snacks or dessert foods) were rice-based.

Baking as a cooking technique was first introduced to Southeast Asia in the colonial era, and charcoal-fired ovens were used for making kueh bahulu and kueh bangkit. The former is a type of small sponge cake baked with eggs, wheat flour and sugar, while the latter is a biscuit made of tapioca flour (Manihot esculenta; a South American native and probably a Portuguese introduction to Southeast Asia), santan (coconut cream), and white or palm sugar. These are traditional festive treats that are still made for occasions such as the Lunar New Year and Hari Raya Puasa (Eid al-Fitr).

Another festive treat is kueh Belanda (meaning “Dutch cake” in Malay), commonly known as “love letters” (crispy egg rolls), which are still best made on a charcoal-fired grill.

Interestingly, a recipe labelled as “Dutch” for Ijzer Koekes, translated as “Iron (thin) Cakes”, was found in a compilation of traditional Sri Lankan recipes first published in 1929.9 The recipe is identical to that for kueh Belanda. What Singaporeans call “love letters” are better known as kueh kapit in Penang, where the thin kueh is folded flat into a triangular shape rather than rolled into a cigarillo-like ijzer koek or love letter.

Tracing Straits-born Cooking

Unlike textiles or pottery, delectable dishes have an ephemeral existence. Fortunately, recipes are almost always transmitted orally within families and communities and many of these traditional recipes have also found their way into cookbooks. This makes tracing the evolution of Straits-born cuisine easier and more accurate.10

What is probably the first local cookbook was The Y.W.C.A. of Malaya Cookery Book: A Book of Culinary Information and Recipes Compiled in Malaya, published in 1931.11 It was edited by Mrs R.E. Holttum, wife of the director of the Singapore Botanic Gardens, and Mrs T.W. Hinch, wife of the principal of Anglo-Chinese School. The book was very well received and went through nine editions, the last in 1962.

The absence of a Straits Chinese category in this book suggests that Straits-born cuisine was not significant before World War II, or even as late as 1962. However, there are a few recipes in the Chinese section labelled as “Straits Chinese”: chicken satay, otak-otak (fish paste mixed with spices, wrapped in banana or coconut leaves and then grilled) and popiah goreng (fried spring roll).

Pork sambal was labelled “Possibly Straits Chinese”. This was a dish cooked with a spice paste consisting of onion, fennel, dried chillies and garlic. This dish is definitively Straits Chinese as traditional Chinese food does not use fennel. One recipe in the book not labelled as Straits Chinese but which looks distinctly so is pig liver balls cooked with ketumbar (coriander) and asam (tamarind) water. The dish resembles a traditional Straits Chinese dish called hati babi (minced liver and pork, shaped into balls).

The Malay section of the YWCA cookbook has many recipes that we would today also label as Straits-born, such as rendang (beef or chicken braised in coconut milk with a spice mix or rempah), opor (chicken cooked in coconut milk with a spice mix) and agar-agar (Spherococcus lichenoides). Agar-agar, a Malay word, is a Southeast Asian seaweed that was once exported to China to be used as a fixative in paper and silk production, but cooked into a dessert jelly in this part of the world, and still is today.12

The first Singapore cookbook with many recognisable Straits-born recipes is My Favourite Recipes by Mrs Ellice Handy, a domestic science teacher.13 This slim publication of 94 pages first came out in 1952 as a fundraiser for the Methodist Girls’ School building fund. With numerous reprints and editions over the years – the latest published in 2014 – the cookbook has since become a classic. It contributed to the spread of Straits-born cooking although only a few of the recipes were defined specifically as Straits-born.

Another domestic science teacher who produced a cookbook for her students was Lilian Lane, who taught at the Malayan Teachers’ College in Penang between 1956 and 1959. Her 1964 Malayan Cookery Recipes Tested in Malayan Schools has identifiably Straits-born recipes: otak-otak, whole fish stuffed with chillies and belacan, mutton kurmah, satay and rojak (described as “Javanese fruit salad”).14 The linkage between rojak and Java is fascinating because 10th-century Javanese copper-plate inscriptions describe “rujak [as] a salad of raw green fruit, mixed with sugar or seasoning”.15

Given that Lane was based in Penang, it is interesting that her rojak recipe did not contain hae ko (black prawn paste), an essential ingredient in today’s Penang and Singapore rojak. It did, however, have belacan mixed with peanuts and teecheo (Chinese sweet black sauce). The flavour of teecheo is the same as Indonesian kicap manis. Perhaps the ancient Javanese rujak used kicap manis in the dressing? Hae ko – which must not be confused with belacan, a basic Southeast Asian ingredient – is a genuine Penang-born product; Penang is still Singapore’s only source of hae ko today.

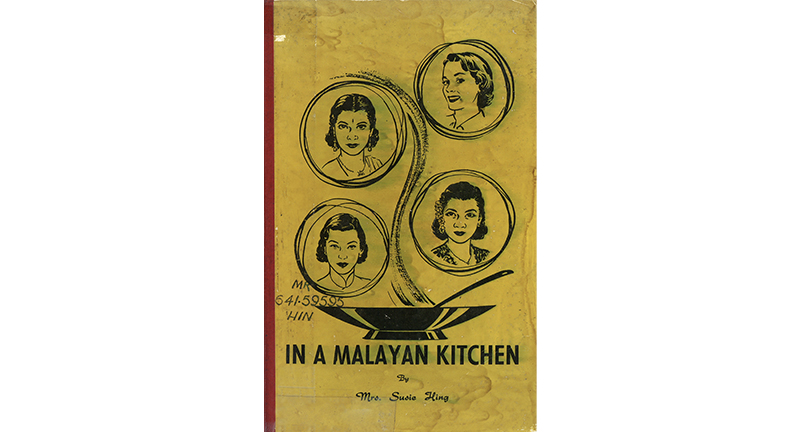

Indonesia’s contributions to Straits-born cuisine in Singapore can be seen in Mrs Susie Hing’s In A Malayan Kitchen, published in 1956.16 Mrs Hing was from Semarang in central Java, the hub of the Indonesian Chinese community during the Dutch colonial era. Several prominent Singaporean families have forebears who hailed from Semarang, among them the Kwa family, the in-laws of the late founding Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew, whose own grandmother and father were born there.17

Mrs Hing’s book had typical Indonesian recipes such as opor ayam, rendang Padang, sate bakso and dendeng manis. This last is a spiced savoury meat rather like Singapore’s bak kwa but dried in the sun instead of being grilled. Dendeng, or dried meat, is a Javanese preparation that dates back to the 10th century, like rujak. An interesting question is whether Indonesian dendeng is the inspiration for bak kwa.

The cookbook also features typical Malayan-Singapore recipes such as roti jala (a lacy pancake eaten with curry), Hokkien mee and pineapple tarts, both the open and the closed pineapple-shaped tarts with spikes that were traditionally seen as Indonesian.

One interesting find in Mrs Hing’s book is a recipe for kroket tjanker or Java kwei patti. This is a dish using deep-fried shells made the same way as today’s kueh pie tee shells. But unlike today’s kueh pie tee, which is filled with shredded bamboo shoots or yam bean, this Java kwei patti has a rich meat filling. Did today’s kueh pie tee start out as a Dutch colonial dish? (The 1960 edition of Mrs Ellice Handy’s My Favourite Recipes has a recipe for kueh pie tee that used a filling of bamboo shoots.18) Note that yam bean or jicama (Pachyrhizus erosus) was originally native to Mexico, and was probably introduced to Southeast Asia during the Spanish colonial era in the Philippines.

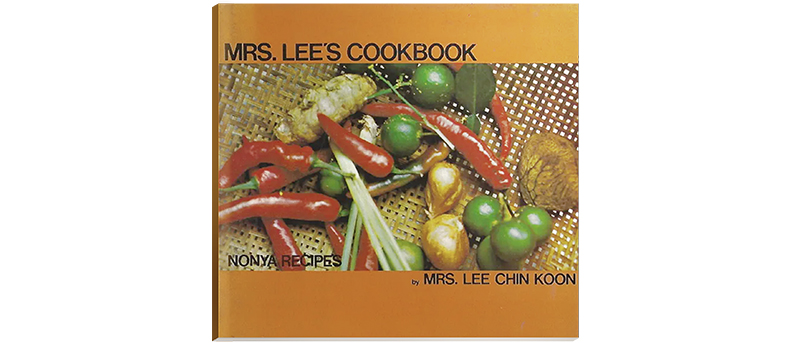

The first local cookbook that identified itself as being Peranakan is Mrs Lee’s Cookbook, originally self-published in 1974.19 (The author – Mrs Lee Chin Koon, née Chua Jim Neo – was the mother of Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew). In her book, she wrote: “Malay influence, because of mingling and intermarriage, has produced a unique Peranakan culture and set of customs distinct from those of the Chinese community who came from China. Our food, which is basically Malay or Indonesian in method and ingredients, were altered to suit our tastes.”

Among the Indonesian influences recorded in her cookbook are recipes for nonya ayam buah keluak (chicken with stuffed buah keluak braised in a spicy tamarind gravy) and the eastern Javanese nasi rawon, which is beef stewed with buah keluak and served with rice. After all, her mother-in-law did come from Semarang.20

Mrs Lee explained that she published the book because “it has been one of [her] ambitions to write a book about Straits Chinese food so that the younger generation, including [her] grandchildren and later their children, will have access to these recipes which were zealously kept within families as guarded secrets.”21

Perhaps similarly inspired, her sister, Mrs Leong Yee Soo, also published her cookbook, Singaporean Cooking, in 1976.22 In the 1970s and 80s, Mrs Lee and Mrs Leong were among the first Peranakan women who were active in spreading knowledge about Straits-born cuisine through cooking classes. Indeed, family recipes were never actually kept secret but usually passed on to family members and favoured friends and through cooking classes.

In all likelihood, all these early cookbooks contained heritage recipes that had been tweaked and modified over time into family favourites.

Preservation and Alteration

In his book, The Traditional Dietary Culture of Southeast Asia, Akira Matsuyama proposes two concepts for studying the dietary culture of the region. One is to look at “conventionality” when traditional food is defined as food that has stood the test of time, and the other is “aboriginality” or the linkage of this food to the inhabitants of the area. Both conventionality and aboriginality are seen in Straits-born cooking. Matsuyama writes: “The preservation of tradition and acceptance of alteration are two aspects of the dietary culture of Southeast Asia.”23

These two trends – preservation and alteration – are hallmarks of Straits cuisine in Singapore. Today, creative cooks and chefs have been experimenting, introducing unlikely, new-fangled combinations such as otak-otak buns and foie gras tau kua pau. At the same time, they have also preserved much of the cuisine’s conventional and aboriginal characteristics.

One of the traits of a great cuisine is its ability to retain its traditional roots while taking on new and interesting flavours with the introduction of non-traditional ingredients. Straits cuisine definitely falls into that category.

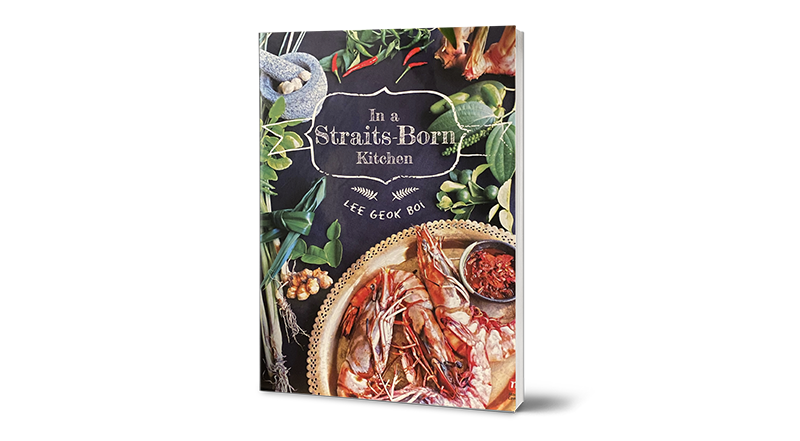

Lee Geok Boi’s newly published cookbook, In a Straits-born Kitchen, by Marshall Cavendish Cuisine features the recipes that she has inherited, collected, tweaked or experimented with over more than half a century. The book is available for reference at the Lee Kong Chian Reference Library and for loan at selected public libraries (Call nos.: RSING 641.5959 LEE and SING 641.5959 LEE). It also retails at major bookshops in Singapore.

Lee Geok Boi’s newly published cookbook, In a Straits-born Kitchen, by Marshall Cavendish Cuisine features the recipes that she has inherited, collected, tweaked or experimented with over more than half a century. The book is available for reference at the Lee Kong Chian Reference Library and for loan at selected public libraries (Call nos.: RSING 641.5959 LEE and SING 641.5959 LEE). It also retails at major bookshops in Singapore.

Lee Geok Boi has a life-long interest in all aspects of food but especially in cooking it. She is the

author of several books and a prolific writer of cookbooks focusing on Asian cuisines and, in particular, Southeast Asian recipes.

Lee Geok Boi has a life-long interest in all aspects of food but especially in cooking it. She is the

author of several books and a prolific writer of cookbooks focusing on Asian cuisines and, in particular, Southeast Asian recipes.

NOTES

-

Eurasians are persons with mixed European and Asian lineage. Most Eurasians in Singapore can trace the European part of their ancestry to the Portuguese, Dutch or British, while others are of Danish, French, German, Italian or Spanish descent. See Ho, S. (2013, July 25). Eurasian community. Retrieved from Singapore Infopedia website. ↩

-

The Chetti Melaka, or Peranakan Indians, are the descendants of Tamil traders who settled in Melaka during the reign of the Melaka Sultanate and married local women of Malay and Chinese descent. National Heritage Board. (2020, November 13). Chetti Melaka of the Straits – Rediscovering Peranakan Indian communities. Retrieved from Roots website. ↩

-

Sengupta, J. (2017, August 30). India’s cultural and civilisational influence on Southeast Asia. Retrieved from Observer Research Foundation website. ↩

-

Kwa, C.G., & Kua, B.L. (Eds.). (2019). A general history of the Chinese in Singapore (p. 9). Singapore: Singapore Federation of Chinese Clan Associations and World Scientific. (Call no.: RSING 305.895105957 GEN) ↩

-

North Carolina Soybean Production Association. (2019). History of soybeans. Retrieved from NC Soybean Producers Association website. ↩

-

Matsuyama, A. (2003). The traditional dietary culture of Southeast Asia: Its formation and pedigree (p. 112). London: Keegan Paul. (Call no.: RSEA 394.10959 MAT) ↩

-

Mintz, S.W. (1985). Sweetness and power: The place of sugar in modern history (p. 19). New York: Viking. (Call no.: RCLOS 394.12 MIN) ↩

-

For more information on kueh lapis, see Tan, C. (2021, Jan–Mar). Love is a many-layered thing. BiblioAsia, 16 (4). Retrieved from BiblioAsia website. ↩

-

Deutrom, H. (2013). Ceylon daily news cookery book (5th ed., p. 261). Colombo, Stamford Lake. (Not available in NLB holdings) ↩

-

Wee, S. (2012). Growing up in a nonya kitchen: Singapore recipes from my mother. Singapore: Marshall Cavendish. (Call no.: 641.595957 WEE); Tan, C. (1983). Penang nyonya cooking: Foods of my childhood. Petaling Jaya: Eastern Universities Press. (Call no.: RSING q641.59595 TAN). There is no cookbook on Chetti food that I am aware of although there are some Chetti-like recipes in Sanmugam, D. (1997). Banana leaf temptations. Singapore: VJ Times. (Call no.: RSING 641.5948 SAN) and Gomes, M. (2001). The Eurasian cookbook. Singapore: Horizon Books. (Call no.: RSING q641.5 GOM) ↩

-

Looking at old locally published cookbooks means looking at Malayan cookbooks. The concept of a Singapore separate from Malaya did not come into being until 1965 when Singapore became an independent republic. The National Library does not have this 1931 edition, but it has the 1937, 1939, 1948, 1951 and 1962 editions. See Holttum, R.E., Mrs, & Hinch, T.W., Mrs. (Eds.). (1937). The Y.W.C.A. international cookery book of Malaya. [Kuala Lumpur]: Malayan Y.W.C.A. (Call no.: RRARE 641.59595 YWA; Microfilm no.: NL29320); Holttum, R.E., Mrs, & Waite, D.S., Mrs. (Eds.). (1939). The Y.W.C.A. international cookery book of Malaya. [s.l.]: Malayan Committee of the Young Women’s Christian Association. (Call no.: RRARE 641.59595 YWC; Accession no.: B29232809B); Llewellyn, A.E., Mrs. (Ed.). (1948). The Y.W.C.A. of Malaya international cookery book. [Kuala Lumpur]: Y.W.C.A. of Malaya. (Call no.: RCLOS 641.59595 YWC); Llewellyn, A.E., Mrs. (Ed.). (1951). The Y.W.C.A. of Malaya & Singapore cookery book: A book of culinary information and recipes compiled in Malaya. [s.l.]: Y.W.C.A. of Malaya and Singapore. (Call no.: RCLOS 641.595951 YWC); Llewellyn, A.E., Mrs. (Ed.). (1962). The Y.W.C.A. of Malaya cookery book; a book of culinary information and recipes compiled in Malaya. [Kuala Lumpur]: Persatuan Wanita Keristian di Malaya, Y.W.C.A. of Malaya. (Call no.: RCLOS 641.59595 YOU) ↩

-

Yule, H., & Burnell, A.C. (1886). Hobson-Jobson: Being a glossary of colloquial Anglo-Indian words and phrases, and of kindred terms; etymological, historical, geographical and discursive (p. 5). London: John Murray. (Call no.: RRARE 422.03 YUL-[JSB]; Accession no.: B29265644E) ↩

-

Handy, E. (1952). My favourite recipes. Singapore: Printed at the Malaya Publishing House Ltd. (Call no.: RCLOS 641.595 HAN-[JK]) ↩

-

Lane, L. (1964). Malayan cookery recipes tested in Malayan schools. Singapore: Printed by Eastern Universities Press for University of London Press. (Call no.: RCLOS 641.59595 LAN) ↩

-

Hing, S., Mrs (1956). In a Malayan kitchen. Singapore: Mun Seong Press. (Call no.: RCLOS 641.59595 HIN-[RFL]) ↩

-

Lee, K.Y. (1998). The Singapore story: Memoirs of Lee Kuan Yew (p. 27). Singapore: Times Editions, Singapore Press Holdings. (Call no.: RSING 959.57 LEE-[HIS]) ↩

-

Handy, E. (1960). My favourite recipes (p. 57.) Singapore: Singapore: Malaya Publishing House. (Call no.: RLOCS 641.595 HAN) ↩

-

Lee, C.K., Mrs. (1974). Mrs. Lee’s cookbook: Nonya recipes and other favourite recipes. Singapore: [The Author]. (Call no: RSING 641.595957 LEE) ↩

-

Leong, Y.S. (1976). Singaporean cooking. Singapore: Eastern Universities Press. (Call no.: RSING 641.595957 LEO) ↩