Mansion Blocks, Flats and Tenements: The Advent of Apartment Living

Through buildings like Amber Mansions, Eu Court and Meyer Flats, colonial architects Swan & Maclaren introduced the concept of apartment living in Singapore, as Julian Davison tells us.

Established in 1892, Swan & Maclaren (named after Archibald Alexander Swan and James Waddell Boyd Maclaren) is the oldest architectural practice in Singapore. Its architects, such as Regent Alfred John Bidwell, Denis Santry and Frank Lundon, designed many of Singapore’s historic buildings, including Raffles Hotel, Teutonia Club (present-day Goodwood Park Hotel), Chesed-El Synagogue, Stamford House, Victoria Memorial Hall and Theatre, and Tanjong Pagar Railway Terminus.

The first 50 years of the firm’s history is detailed in Julian Davison’s Swan & Maclaren: A Story of Singapore Architecture, published by ORO Editions and the National Archives of Singapore in 2020. In this edited extract from Chapter 30, the author looks at some of the earliest apartment buildings in Singapore built by the firm. Note: Apart from the David Elias Building on Middle Road and the two rows of shophouses next door, all the other apartment blocks mentioned in this essay have been demolished.

The late flourishing of the black-and-white house notwithstanding, the residential architecture of Singapore in the early 1920s was notable for the emergence of a new way of living, namely the residential apartment block. In the West, the modern middle-class apartment dwelling has its origins in Baron Haussmann’s reconstruction of Paris in the 1850s.1

The idea gradually spread to other European cities and eventually the Americas – significantly, the Stuyvesant Apartments on East 18th Street. Generally recognised as New York’s first purpose-built apartment block, it was designed by the Paris-trained architect Richard Morris Hunt in 1869 and was often referred to as the “French Flats”.

In Singapore, the earliest apartment dwelling per se was probably the Elias Building at the junction of Niven and Wilkie roads, followed by Manasseh Meyer’s Crescent apartments in Tanjong Katong in 1912 and Meyer Mansions on North Bridge Road in 1918, all designed by Swan & Maclaren.

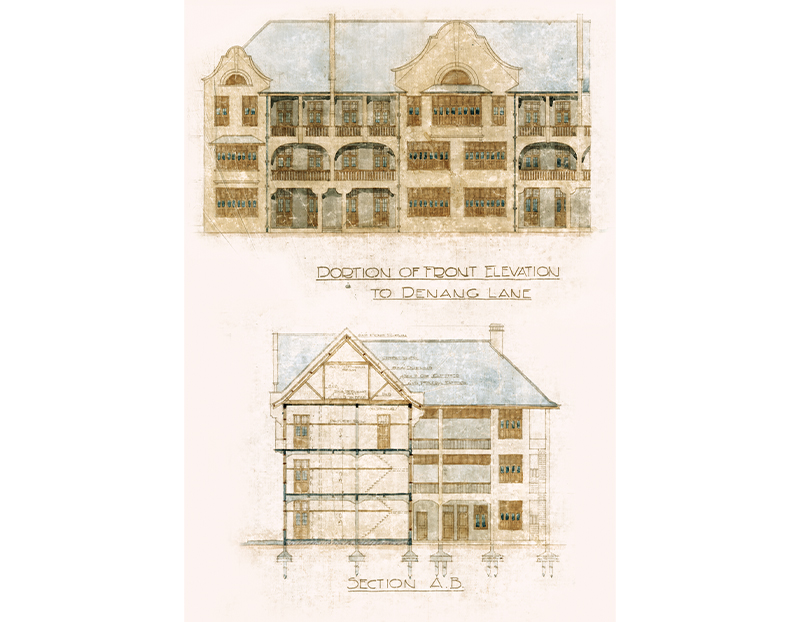

Amber Mansions, Orchard Road, 1920–22

After World War I (1914–18), the idea began to gather traction in a big way. The most prominent of the early post-war apartment blocks was Amber Mansions at the junction of Orchard Road and Penang Lane. Commissioned by the Singapore Building Corporation in 1919, Amber Mansions is often hailed as Singapore’s first apartment block; clearly it wasn’t. It is also often singled out for special mention as Singapore’s first shopping centre. It wasn’t that either.

Nevertheless, Amber Mansions was an important and innovative building that was popularly associated in the public’s imagination with the emergence of a modern lifestyle in the years between the two world wars. It remained an architectural landmark symbolising that era until its demolition in 1984 to make way for Dhoby Ghaut MRT Station.

The Singapore Building Corporation, despite its civic-sounding name, was actually a property development company owned by influential Jewish businessman Joseph Aaron Elias, better known as Joe Elias.2 The three-storeyed Amber Mansions at the bottom end of Orchard Road was named after the Elias family’s Jewish clan name; Amber Road, where the Elias family owned a lot of property, came by its name the same way.

Joe Elias’s father, A.J. Elias, was one of the pioneers of apartment living in Singapore with his Bidwell-designed, two-storey duplex development at the junction of Wilkie and Niven roads.3 It was an experiment that his son determined to repeat, albeit several years after the death of Elias senior in 1902.

Drawings submitted to the Municipality for planning permission reveal that Amber Mansions was originally intended to be entirely residential, but subsequently the ground floor was remodelled to be rented out as commercial premises – Malayan Motors and the Municipal Gas Department were among the first tenants. Several of the residential units on the floors above were likewise redesigned as office spaces, which were then taken up by lawyers and architectural practices.

Viewed from the junction of Orchard Road and Dhoby Ghaut, the most striking feature of Amber Mansions was its bowed elevation as the building turned the corner from Orchard Road into Penang Lane, surmounted by a large Dutch gable.4

Perhaps more significant, architecturally, was the complete absence of any Classical ornament or detailing, the facades being more or less stripped of all surface decoration. Broad, flattened arches spanned the intervals between the piers of the five-footway verandah at street level, while the Dutch gable that articulated the corner was repeated at intervals along each wing. Otherwise, the building wore an uncommonly severe facade.

Amber Mansions cost around $400,000 to build, the contracting work being undertaken by Soh Mah Eng, who was Swan & Maclaren’s regular partner in the post-war era.

Completed in early 1922, the apartments were initially a little hard to dispose of, owing to a downturn in the Singapore economy as a result of the depression in the United States (1920–21). However, following a shareholders’ meeting in December that year, when the Singapore Building Corporation decided to lower the rents by between $20 and $25 per unit (the upper range previously had been $175 per month), they were snapped up quite speedily. The fact that the residential units were so easily dispensed with in difficult times was indicative of the fact that apartment living was a fashionable, as well as affordable, modern lifestyle choice.

The retail units were a little harder to let and a year later, there were still eight units vacant. The directors of the company, however, were “confident that the class of shopkeeper who seems glued to High Street at exorbitant rents will sooner or later recognise the advantage of carrying on his trade in what is undoubtedly the principal European thoroughfare in town”.5 And so they did.

Institution Hill Mansions, River Valley Road, 1920

Institution Hill Mansions on River Valley Road date from the same year as Amber Mansions and were designed by Swan & Maclaren for their regular engineering partners, United Engineers. (The latter was formed in 1912 through the amalgamation of Howarth Erskine & Co., Swan & Maclaren’s long-standing collaborators, with Riley, Hargreaves & Co., Singapore’s oldest engineering firm.)

Erected at a cost of $290,000, the Institution Hill apartments were primarily intended to provide accommodation for United Engineers’ European staff members. The initial scheme would comprise two residential blocks, each with three storeys and 18 units, although eventually only one block was built.

The layout of the apartments was quite similar to Amber Mansions and consisted of a living room, dining room and two bedrooms, with a shared bathroom and a box room for storage; there was also a “boy’s room” attached to the kitchen for a live-in domestic servant. Although the external elevations were unmistakably “modern” in their restrained detailing, they were less austere than Amber Mansions. With their Mock Tudor gables and loggia-style verandah-balconies, they represent a kind of Arts and Crafts take on the apartment lifestyle.6

Eu Court, Hill Street and Stamford Road, 1925

Although Amber Mansions was well received upon completion in early 1922, it would be another three years before Swan & Maclaren received their next commission for an apartment block. It came from businessman and philanthropist Eu Tong Sen (who built up Chinese medicine purveyor Eu Yan Sang) and was for a three-storey, L-shaped block of flats at the corner of Hill Street and Stamford Road.7

There were to be eight retail units on the ground floor and as many residential apartments on each of the floors above. The latter offered a choice of two- or three-bedroom flats, with a living room, dining room and kitchen. There were garages, too – a sign of the times – with servants’ quarters above that were located across a courtyard at the rear of the property.

Architecturally, the style was “Stripped Classical”, a kind of reductive Classicism popular in the early decades of the 20th century, where the details have been greatly simplified, or stripped away, but there is still an adherence to the principles of Classical architecture in terms of symmetry, proportion and the arrangement of the elevation.8

The most striking feature, however, was a Chinese-style rooftop pavilion, or gazebo, which articulated the meeting of the two wings, the one on Hill Street, the other on Stamford Road. The latter added a local touch to what would otherwise have been a wholly modern building – Chinese Art Deco would probably be the best description.

Popularly known as Eu Court, this landmark building aroused considerable controversy when it was demolished in 1992 to allow for the widening of Hill Street. In the end it was a toss-up between Eu Court or Stamford House as to which should go, and Eu Court was the loser.

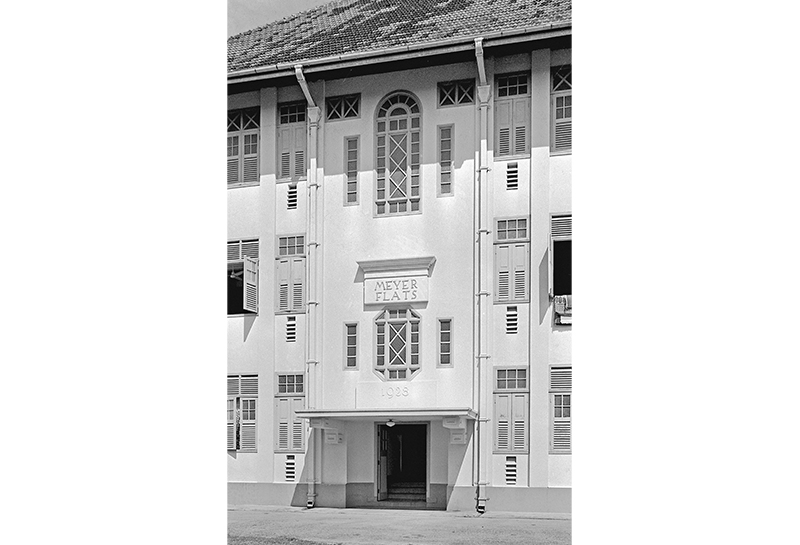

Meyer Flats, Katong, 1927–28

The Elias Building aside, the earliest apartment block to be erected in Singapore was The Crescent on Meyer Road designed by Regent Alfred John Bidwell for Jewish businessman Manasseh Meyer in 1912.9 In 1927, a companion block was commissioned for the site next door, comprising 12 commodious units spread over three floors.

Neighbours they may have been, but stylistically, these two buildings were worlds apart – The Crescent, a gracious study in tropical Edwardian elegance and charm; the newcomer, devoid of extraneous embellishments, with the details of the facade pared down almost to the point of parsimony. Indeed, the most striking aspect of the latter building is what is absent, namely balconies and verandahs, a surprising omission given the building’s seaside location.

In the case of the Meyer Flats, as the new arrival was christened, the grid-like distribution of the windows, each with a tiled air vent below the sill, allowed for a limited kind of pattern-making. Otherwise, the only part of the building that was singled out for particular attention were the two entrances at either end of the seaward elevation and the stairwells that were placed over them. They were identical and came with a flat, reinforced-concrete canopy roof over the front door, above which was positioned a large octagonal window with the name “Meyer Flats” emblazoned across the top. This window lit the entrance lobby and stairwell, while a second window, a quasi-Venetian affair this time around, illumined the upper stairwell and top landing.

These details aside, Meyer Flats was an austere building, in sharp contrast to The Crescent next door. The latter, with its open verandahs and generous fenestration (arrangement of windows), was purpose-built to make the most of the sea breezes by way of natural ventilation.

Meyer Flats, on the other hand, was essentially a European-style building, being much more closed in, with modest window openings and an absence of verandahs and balconies. Indeed, apart from the louvered shutters and tiled air vents, the only real concession to Singapore’s monsoon climate was the high, hipped roof and broadly extended eaves.

In this respect, Meyer Flats can be seen as representative of a gradual shift towards a more European style of residential architecture that took place in Singapore between the wars. Similar changes were taking place in the archetypal Singapore house which, by the late 1920s, had begun to move away from the traditional Anglo-Malay-style bungalow or villa that had defined the residential architecture of colonial Singapore more or less since the days of Raffles, towards more compact, European-style houses, with smaller windows, lower ceilings and greatly reduced verandah areas.

In both instances, what we see is a kind of Europeanisation of the building character that corresponded with a more Western-oriented outlook and lifestyle on the part of Singapore’s expatriate community. In this last respect, Meyer Flats represents a parallel development to the “mansion-block” housing schemes that were popular in London at around the same time.

David Elias Building, Middle Road, 1927–28

Amber Mansions, Institution Hill Mansions and Meyer Flats: three upmarket residential developments that were evidently built with a European clientele in mind – their respective locations and self-aggrandising designation as “mansions” for the first two indicate as much.10

Likewise, the apartment blocks commissioned by Eu Tong Sen at the junction of Stamford Road and Hill Street. Which is not to say that there was any overt colour bar in place that would have prevented members of Singapore’s emerging Asian middle class – businessmen, office staff, clerical workers, school teachers and even young professionals – from renting a unit in one of these apartment blocks. If they could afford it, that is. But then somewhere in between the purpose-built apartment block and the shoebox cubicle of the repeatedly subdivided shophouse, there was a kind of halfway house – the tenement.

The word “tenement” today comes with pejorative associations but in the 1920s, the dictionary definition of a “tenement house” was simply “a dwelling house erected or used for the purpose of being rented, esp. one divided into separate apartments, or tenements, for families”.11

In Singapore, the term only begins to appear in planning submissions to the Municipal Engineer after World War I, usually in connection with the laudable efforts of civic-minded individuals and charitable organisations looking to provide decent but affordable housing for less well-off sectors of society; the “tenement”, like the “flat”, was a new building typology.

The first designated tenement accommodation designed by Swan & Maclaren is a landmark development from 1927, the David Elias Building at the corner of Middle Road and Short Street.

David Elias was a second cousin of Joe Elias and also his brother-in-law, as he had married Joe’s sister Miriam. David was in the import-export business, but in 1926 he decided to follow Joe into real estate with the redevelopment of a site at the junction of Middle Road and Selegie Road.

At the time, the land was occupied by a single “compound house”, standing in its own grounds.12 As the footprint of the house was small, relative to the size of the property, and in a densely populated neighbourhood of overcrowded shophouse dwellings that constituted Singapore’s Jewish quarter, or Mahallah, it seemed to David that the site could be used in a more beneficent way.

To this end, David commissioned Swan & Maclaren to design two rows of two-storey “tenement shophouses” on Short Street and also next door, at the junction of Middle Road and Short Street, a much larger, three-storey construction, today’s David Elias Building. The latter had shops and offices on the ground floor, with tenement apartments on the floors above.

Part of the ground floor of the David Elias Building was occupied by David and Joe’s own business, D.J. Elias and Company, with Messrs Cold Storage & Co. as the anchor tenant. This was one of Cold Storage’s first ventures outside of Orchard Road, where the importer of frozen comestibles had first set up shop in early 1905.

In truth, the tenement-shophouses were not much different in terms of their layout and internal arrangements to the typical Singapore shophouse of the period, but there is something about these buildings that is reminiscent of similar housing typologies in contemporary Shanghai called lilong.13 Possibly it is the Shanghai plaster rendering that brings the association to mind, or the cantilevered bay windows on the upper storey, which are rather different from the usual shophouse fare and which help to contribute to the slightly exotic flavour of these buildings.

The windows themselves are doubly unusual on account of the “blind” balustrading beneath the window sills, comprising pre-cast concrete balusters (series of pillars supporting a railing) that echo traditional wooden balusters turned on a lathe.

The David Elias Building next door, though much larger in scale – three storeys instead of two, with a hipped roof – is stylistically very similar to its neighbours, sharing a rusticated basement floor with segmental arches spanning the five-footway as well as those distinctive cantilevered bay windows on the floors above.

A Jewish “Star of David” motif appears at regular intervals on the main elevations – this was, after all, at the heart of the Mahallah – and also adorns the two Deco-style pediments, which bookend the Middle Road elevation; the latter also bear the legend “D.J. Elias Buildings” and the date of completion, which was 1928.

Completed in September that year, David Elias’s new venture was hailed by The Straits Times as “an important addition to the housing amenities of Singapore”.14 “Built on a site which was previously occupied by a single house and compound,” the article continues, “they afford, at reasonable rents, very acceptable housing accommodation in a congested district”.

Not only was David Elias “to be congratulated on a well designed block of buildings”, but also for demonstrating “how sites in the centre of town can be used to the best advantage… in striking contrast to the old wasteful shophouse properties which are their immediate neighbours”.

Commendable though the D.J. Elias Building may have been, it was, however, but a very small step in the right direction, given the huge housing problems Singapore faced at the time.

Swan & Maclaren: A Story of Singapore Architecture (2020) is published by ORO Editions and the National Archives of Singapore. The book is available for reference at the Lee Kong Chian Reference Library and for loan at selected public libraries (Call nos.: RSING 720.95957 DAV and SING 720.95957 DAV). It retails at major bookshops in Singapore and is also sold online.

Swan & Maclaren: A Story of Singapore Architecture (2020) is published by ORO Editions and the National Archives of Singapore. The book is available for reference at the Lee Kong Chian Reference Library and for loan at selected public libraries (Call nos.: RSING 720.95957 DAV and SING 720.95957 DAV). It retails at major bookshops in Singapore and is also sold online.

Dr Julian Davison is an anthropologist, architectural historian and former Lee Kong Chian Research Fellow of the National Library, Singapore. He grew up in Singapore and Malaysia, but currently lives here as a writer and television presenter, specialising in Singapore architecture and local history.

Dr Julian Davison is an anthropologist, architectural historian and former Lee Kong Chian Research Fellow of the National Library, Singapore. He grew up in Singapore and Malaysia, but currently lives here as a writer and television presenter, specialising in Singapore architecture and local history.

NOTES

-

Georges-Eugène Haussmann, commonly known as Baron Haussmann (1809–91), was a French official who served as prefect of Seine (1853–70) and was chosen by Emperor Napoleon III to carry out a massive urban renewal programme of new boulevards, parks and public works in Paris. ↩

-

For more information about Joseph Aaron Elias, see Chia, J.Y.J. (2017). Joseph Aaron Elias. Retrieved from Singapore Infopedia website. ↩

-

The architect who designed A.J. Elias’ two-storey building was Regent Alfred John Bidwell, who joined Swan & Maclaren in 1895. He became a partner in 1899. ↩

-

A gable is the triangular-shaped top part of a wall that meets the sloping roofs of a building. A Dutch gable has curved sides rather than straight sides. ↩

-

Company meetings. Singapore Building Corporation. (1923, December 26). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, p. 4. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

A loggia is a design feature of Italian origin and refers to an arcaded gallery or corridor, open on at least one side and affording a protected seating place with a view. The Arts and Crafts Movement, which emerged in England in the latter half of the 19th century, was an aesthetic movement in the decorative and fine arts. This movement later spread to Europe and America. ↩

-

For more information about Eu Tong Sen, see Chow, A. (2014, September 15). Eu Tong Sen. Retrieved from Singapore Infopedia website. ↩

-

Classical architecture originated in ancient Greece and Rome, and is characterised by symmetry, regular proportions, columns, and the use of stone or marble as a primary building material. ↩

-

For more information about Manasseh Meyer, see Tan, B. (2010). Manasseh Meyer. Retrieved from Singapore Infopedia website. ↩

-

In Britain, the use of the word “mansion” (usually in the plural) to describe a block of flats was something that crept in during the late 19th century as property developers tried to encourage an emerging generation of middle- and upper-class urbanites to buy into what at the time was a wholly new residential typology – it lent a “touch of class”, or so people thought. ↩

-

Harris, W.T., & Allen, F.S. (Eds.). (1923). Webster’s new international dictionary of the English language, based on the international dictionary of 1890 and 1900 (p. 2127). Springfield, Mass., USA: G. & C. Merriam Company. Retrieved from Internet Archive website. ↩

-

The term “compound house” refers to a free-standing dwelling situated on its own land, the latter being typically surrounded by a masonry wall on all sides, especially in an urban setting. The etymology of the term “compound”, as used in this content, as opposed to, say, a chemical compound, is said to have come from the Malay word kampong, or village. ↩

-

Li means neighbourhood and Long means lane. A lilong is a type of housing that developed in Shanghai in the 19th century and is a characteristic of the city. It melds Western architectural details with traditional Chinese spatial arrangements. ↩

-

Buildings in Singapore. (1928, September 15). The Straits Times, p. 10. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩