Ancient Gold in Southeast Asia

Where did ancient gold come from? What was it used for and what gold discoveries have been made in Singapore? Foo Shu Tieng has the answers.

Gold is a precious commodity admired for its beauty, rarity and monetary value. To understand how it became such a valued metal in Southeast Asia specifically, we need to look at the historical,1 archaeological2 and ethnographic3 evidence.

Why write about it now? With the price of gold at an all-time high, many ancient historical sites in Asia, especially those believed to contain gold jewellery and artefacts, are being looted.4 If the trafficking of antiquities is left unchecked, the potential loss of knowledge and heritage would be devastating. For example, the ancient burial site of Bit Meas in Prey Veng province, Cambodia (estimated 150 BCE to 100 CE), was almost completely looted in early 2006 by treasure hunters.5 While local authorities have since put in place mitigation policies and experts have issued recommendations to deal with illegal antiquities trafficking, these may not be sufficient and greater community awareness is needed.6

Singapore has not been spared from the ravages of treasure hunters either. In 1949, a section of Stamford Road in the civic district – an area with potential 14th-century Temasek period finds – was dug for “buried treasure” supposedly left behind from the days of the Japanese Occupation (1942–45).7

The Early Gold Trade

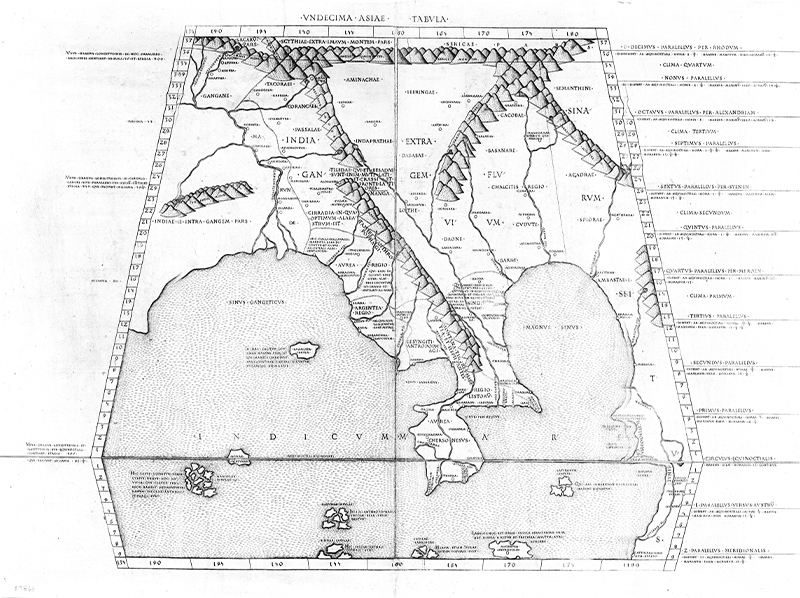

It was in 4th century BCE that Southeast Asia began to be associated with names such as “Land of Gold” (Suvaṇṇabhūmi), “Wall of Gold” (Suvarṇakudya), “Islands of Gold” (Suvarṇadvīpa) and “Golden Peninsula” (Khersonese).8

One theory why the region was associated with gold is that sometime around 300 BCE, there was a disruption in the trade caravans supplying Siberian gold via the Silk Road to South Asia (specifically the Mauryan empire, which at its height, included north and central India, and what is now part of Iran, Pakistan and Afghanistan). Nomadic invaders destroyed several cities in the Margiana and Aria regions (present-day eastern Turkmenistan and western Afghanistan respectively) just before 290 BCE, for example.9 This trade route was not restored until Roman Emperor Nero’s reign (r. 54–68 CE). However, when he tried to debase the gold content in Roman coinage to counter inflation, this led to Roman gold coins becoming less accepted for commercial transactions in South Asia where they were used as bullion.

The supply of gold to South Asia was further hampered by Roman monetary and precious metal controls in 2nd century CE.10 Roman Emperor Vespasian (r. 69–79 CE), for example, issued regulations that prohibited the exports of precious metals from the Roman Empire. The scarcity of precious metals such as gold thus might have encouraged South Asians to seek out new sources of gold in Southeast Asia.

Another theory is that an increased demand in prestige goods encouraged South Asians to explore the Southeast Asian region.11 Sinitic influence is also possible but this theory has not been fully explored.12 Such theories, however, do not take into account the role of Southeast Asians in actively procuring gold nor their participation in various aspects of the gold trade value chain.

The ancient maritime trade between Southeast Asia and South Asia prior to the 1st century BCE shows that there was a two-way transmission of material goods between the two regions. The nut of the areca palm, fruits such as citron, mango and banana, and sandalwood were known to have been transported westward into parts of South Asia and Africa during the prehistoric period.

Meanwhile, Indian rouletted ware (a kind of pottery with rouletted designs at the base)13 has been found in various parts of Southeast Asia such as the Malay Peninsula, Thailand, Vietnam, Java and Bali by the 1st century BCE.14 The gold trade in Southeast Asia would have initially relied on existing trade networks.

Ancient Literary Sources

Abū Zayd al-Sīrāfī’s 9th–10th century Arabic Accounts of China and India (Akhbār al Ṣīnwa-l-Hind) carries an early traveller’s tale of how gold collected during a Javanese king’s reign was redistributed among his subjects after his death and became a measure of the king’s glory.15

According to the account, every morning, “the king’s steward would bring an ingot of gold [and] place the ingot in [a tidal] pool [that adjoined the royal palace]. When the tide came in, the water covered this and the other ingots collected together with it, and submerged them; when the tide went out, the water seeped away and revealed the ingots; they would gleam there in the sunlight, and the king could watch over them when he took his seat in the hall overlooking them”.16

This continued every day for as long as that particular king lived. Upon his death, the ingots were “counted, melted down and shared out among the royal family, men, women, and children, as well as among their army commanders and slaves, each according to his rank and to the accepted practice for each class of recipients. Any gold left over afterwards would be distributed to the poor and needy”. The final number and weight of the gold would be recorded, and it was said that the “longer a king reigned and the more ingots he left on his death, the greater his glory in the people’s eyes”.17

Chinese texts such as Wang Dayuan’s18 (汪大渊) 島夷志略 (Dao Yi Zhi Lue; A Brief Account of Island Barbarians, dated 1349) and Fei Xin’s19 (费信) 星槎勝覽 (Xing Cha Sheng Lan; The Overall Survey of the Star Raft, dated 1436) cite gold as an important strategic resource for Southeast Asia.20 The texts mention that the seats for nobility in the kingdom of Chenla (真臘; Zhenla) (now parts of Cambodia and Laos) were made of gold; that everyone used gold tea trays, as well as plates and cups made of gold; that the royal cart for the sovereign was made of gold; and that gold was accepted as a medium of exchange.21

Current Chronology for Gold

Currently, the earliest gold finds in the world date to the mid-5th millennium BCE in the regions north and west of the Black Sea.22 As more and more communities began to view goods made with this new medium as precious and exotic, gold began to be traded more widely.

In India, gold has been found in graves dating to the first millennium BCE and possible early mining sites have also been identified.23 In China, gold was used for personal ornaments in the northwest during the Western Zhou period (11th to 8th century BCE).24

The first gold ornaments in Southeast Asia were South and West Asian prestige goods that appeared around 400 to 300 BCE. Sites such as the Tabon Caves in Palawan in the Philippines, Giong Ca Vo in Vietnam and Khao Sam Kaeo in southern Thailand yield evidence of some of the earliest gold discovered in the region.25

Obtaining Gold

Generally, there are two ways of obtaining gold from nature: panning and mining. Panning does not leave archaeological traces and no equipment or specialist knowledge is needed. However, mining does, and in Southeast Asia, gold mining has been generally reported for the late historic periods.26 Some mines had the support of royalty and when raw materials were depleted from an area, the polity would move its base to a more lucrative area.27

Historically, gold was produced in Perak, Kelantan, Pahang, Negeri Sembilan, Melaka and Patani on the Malay Peninsula; the Barisan mountain range in West Sumatra; western Borneo; Luzon and Mindanao in the Philippines; Timor; northern Burma; northern and central Vietnam; Laos; as well as the Oddar Meanchey, Preah Vihear and Rattanakiri provinces in Cambodia.28

Making Gold

Smithing in Southeast Asia was considered specialist knowledge and associated with mantras, rituals and offerings. A Karo29 goldsmith in Sumatra, for example, would mutter certain prayers and present “the blood, heart, liver and lungs of a scaly, red chicken and also some lombok [chili]” as an offering to “wake up” his tools and appease them before beginning his work.30

Temple reliefs depicting smithing activities, such as those of Candi Sukuh in central Java, signified their importance in society, where the metal was sometimes used for Hindu-Buddhist temple consecration deposits.31 Smiths were mentioned in Javanese and Balinese inscriptions in the 9th to 10th century CE, and taxed according to the number of bellows they had.32

Smithing sites are generally identified through excavations, surveys and interviews with local informants, and by finding tools (furnaces, blowpipes or bellows and tuyères [ceramic or stone tubes] as well as ceramic crucibles) and by-products (slag).33

Using Gold

One theory explaining why gold became so popular in Southeast Asia is that gold ornaments and other gold trade objects were likely carried or worn by visiting traders, and “visually communicated special status”. These material goods would have assisted regional elites in forging alliances by exchanging the items during marriages and ritual gifting, for example.34

Gold ornaments were part of early long-distance trade networks and the gold artefacts found at the stone sarcophagus burial site of Pangkung Paruk on Bali (2nd to 4th century CE) seems to support this. The site yielded gold-glass beads typically found at Western Indian Ocean sites as well as gold ornaments which were tested and found to be similar to those discovered at Giong Ca Vo in Vietnam and Khlong Thom in Thailand.35

Gold in Singapore

In Singapore, 10 ancient gold ornaments said to be related to the Majapahit empire36 were accidentally discovered in 1928 during excavation works for the construction of a reservoir at Fort Canning. These items may have been deliberately hidden, possibly during a Siamese attack37 at the end of the 14th century.38 Only four ornaments remained after the Japanese Occupation; the whereabouts of the other six are unknown.39 The kāla motif40 on one of the ornaments is said to be similar to a belt from a Mahākāla statue41 from Padang Roco in Sumatra. Other ornaments with kāla heads have also been discovered in Java.42

Were the gold ornaments found in Singapore part of royal regalia, made by Majapahit artisans? Geologically, Singapore does not have native gold, so the gold would have to be imported.43 Further trace element analysis on the artefacts, such as those done for other assemblages from Southeast Asia, may provide clues that point to a more precise point of origin but as gold is often recycled, the results may not be conclusive.44

Archaeological excavations in Singapore carried out between 1984 and 2017 have uncovered additional pieces of gold at Fort Canning and other sites in the civic district, consisting of small ornament fragments or gold foil, interpreted as part of secondary deposits.45 The 1994–95 excavation of the Parliament House site, for example, yielded a few pieces of gold artefacts: part of a jewellery strap; a sheet fragment with incised decoration; part of a ring; as well as a piece of “irregularly” shaped foil, possibly for rework by a goldsmith.46

According to ancient Javanese inscriptions from the 9th to 10th century CE, there were two types of jewellery artisans. The first category lived within the palace compound and made ornaments solely for the royal family. The second category fulfilled village commissions, with the ring makers (pasisim in Old Javanese) considered a special class of jeweller.47 This is because gold rings with auspicious inscriptions (simsim prasada mas in Old Javanese) may also have been used as “special purpose” currency for temple donations and ritual offerings.48 This may have been the case for ancient Temasek.

Gold was a medium of exchange on the island in the 14th century. Chinese traders used something called “red gold” (紫金) as a form of currency in places such as Longyamen (龍牙門) and Banzu (班卒) on the island, thought to be located at or near the Singapore Straits.49

If lead or mercury vessels were found, this could be evidence of local gold working as these vessels were used to help separate gold from the ore. There is a theory that a type of stoneware jar found in large numbers in soil layers dating to the 14th century in several sites in Singapore, as well as other sites in Southeast Asia such as Kota Cina in Sumatra and Kedah and Pahang on the Malay Peninsula, were used for that very purpose. However, a recent study has cast doubt on this theory as the shape of the vessel is unlikely to be suited for carrying mercury.50

Another opportunity for the study of gold artefacts in Singapore is the octagonal gold cup from the Tang dynasty shipwreck discovered by fishermen near the island of Belitung, Indonesia, in 1998. (This was the wreck of an Arabian dhow that might have sunk around 830 CE on its return journey from China to Arabia.) The gold cup may have been made by Tang artisans in the style of Sogdian51 silverware from Central Asia from the mid-700s CE. Why the cup was in a ship in Southeast Asian waters is a mystery yet to be fully solved.52

Further Research

While some strides have been made in the study of gold in Southeast Asia, there are still some research gaps that need to be filled. Exploring the history of mining in the region can help with gold sourcing studies, for example. In addition, scholars have begun to collate historical, ethnographic and archaeological data on gold and present these as part of a geographic information system to analyse gold trade networks.53

Although modern scholarship continues to advance our knowledge of ancient gold in the region, the ability to uncover such information is becoming more difficult due to illicit trafficking of antiquities. Therefore, we have to ensure that such tangible heritage be safeguarded and documented where possible for the benefit of future generations.

Foo Shu Tieng is an Associate Librarian with the National Library, Singapore, who works with the Singapore and Southeast Asia collections. Her responsibilities include collection management, content development as well as providing reference and research services. Her publications on ancient money, shell middens and salt can be found on ResearchGate.

Foo Shu Tieng is an Associate Librarian with the National Library, Singapore, who works with the Singapore and Southeast Asia collections. Her responsibilities include collection management, content development as well as providing reference and research services. Her publications on ancient money, shell middens and salt can be found on ResearchGate.NOTES

-

Ancient pre-colonial literary sources for Southeast Asia were either stone engravings, perishable palm leaf manuscripts, or traveller’s tales and trade compendiums from other regions. See Noboru Karashima and Y. Subbarayalu, “Ancient and Medieval Tamil and Sanskrit Inscriptions Relating to Southeast Asia and China,” in Nagapattinam to Suvarnadwipa: Reflections on the Chola Naval Expeditions to Southeast Asia, ed. Herman Kulke, K. Kesavapany and Sakhuja Vijay (Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, 2009), 271–91. (From National Library, Singapore, Call no. RSING 959.01 NAG); Dick van der Meij, Indonesian Manuscripts from the Islands of Java, Madura, Bali and Lombok (Leiden: Brill, 2017). (From National Library, Singapore, Call no. RSING 091.095998 MEI); Stewart Gordon, When Asia was the World (New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press, 2008). (From National Library, Singapore, Call no. R 950.099 GOR) ↩

-

Archaeology can contribute to known records by offering data where there are no historical sources to be found, such as in the development and dating of ancient gold, and for mining, smithing and the chronology of gold as a measure of value. See John N. Miksic, “Gold: The Perspective of an Archaeologist,” in Old Javanese Gold (4th–15th Century): An Archaeometrical Approach, ed. Wilhelmina H. Kal (Amsterdam: Royal Tropical Institute, KIT Press, 1994), 15–17. (From National Library, Singapore, Call no. RSEA 739.227 OLD); “What is Archaeology,” Society for American Archaeology, accessed 10 August 2021, https://www.saa.org/about-archaeology/what-is-archaeology. ↩

-

Ethnographic accounts are the descriptive study and analysis of a particular human culture and studies focusing on industries, and craftsmen’s workshops can be used to construct useful frames of reference. See Lewis W. Binford. Constructing Frames of Reference; An Analytical Method for Archaeological Theory Building Using Ethnographic and Environmental Data Sets. (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2001). (Not available in NLB holdings) ↩

-

Jose Eleazar R. Bersales, “Looking for Yamashita’s Gold,” Philippine Quarterly of Culture and Society 44, nos. 3 and 4 (2016): 183–210. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website) ↩

-

Andreas Reinecke, Vin Laychour and Sonetra Seng, The First Golden Age of Cambodia: Excavation at Prohear (Bonn: Andreas Reinecke, 2009), 19–21, ResearchGate, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/274251428_2009_The_First_Golden_Age_of_Cambodia_Excavation_at_Prohear_with_Khmer_abstract_Bonn. ↩

-

Denis Byrne, “The Problem with Looting: An Alternative Perspective on Antiquities Trafficking in Southeast Asia.” Journal of Field Archaeology 41, no. 3 (20 June 2016): 344–54, Taylor & Francis Online, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/00934690.2016.1179539. ↩

-

“Stamford Road Treasure Mystery Solved: Aussies Buried Heavy Box,” Morning Tribune, 11 February 1949, 3; “Stamford Rd Treasure Hunt Banned,” Singapore Free Press, 3 May 1949, 5; “Singapore Stands to Lose What Treasure Hunters Find,” (1985, March 15). Straits Times, 15 March 1985, 13. (From NewspaperSG). For more information about 14th-century Temasek, see John N. Miksic, Singapore & the Silk Road of the Sea, 1300–1800 (Singapore: NUS Press, 2013). (From National Library, Singapore, Call no. RSING 959.57 MIK-[HIS]) ↩

-

Paul Wheatley, The Golden Khersonese: Historical Geography of the Malay Peninsula Before A. D. 1500 (Kuala Lumpur: University of Malaya Press, 1966), 123–62, 177–84. (From National Library, Singapore, Call no. RCLOS 959.5 WHE); George Cœdès, The Indianized States of Southeast Asia (Honolulu: East-West Center Press, 1968), 40. (From National Library, Singapore, Call no. RSING 959 COE); Himansha Prabha Ray, “In Search of Suvarnabhumi: Early Sailing Networks in the Bay of Bengal,” in Indo-Pacific Prehistory Association Bulletin 1990: Proceedings of the 14th Congress of the Indo-Pacific Prehistory Association, Yogyakarta, Indonesia, 26 August to 2 September 1990, ed. Peter Bellwood (Canberra: Indo-Pacific Prehistory Association, 1990), 357. (From National Library, Singapore, Call no. R 930 IND) ↩

-

Ahmad Hasan Dani and P. Bernard, “Alexander and His Successors in Central Asia,” in History of Civilizations of Central Asia: The Development of Sedentary and Nomadic Civilizations, 700 B. C. to A. D. 250, ed. János Harmatta, B. N. Puri, and G. F. Etemadi (Paris: UNESCO Publishing, 1992), 2: 89. (From National Library, Singapore, Call no. RU 958 HIS); Ray, “In Search of Suvarnabhumi,” 357; Irfan Habib and Faiz Habib, “Mapping the Mauryan Empire,” Proceedings of the Indian History Congress 50, Golden Jubilee Session (1989), 57–79. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website. ↩

-

Cœdès, The Indianized States of Southeast Asia, 20; William Woodthorpe Tarn, The Greeks in Bactria & India (London: The Syndics of the Cambridge University Press, 1922), 104–9, Internet Archive, https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.125997/page/n125/mode/2up; Kenneth R. Hall, Maritime Trade and State Development in Early Southeast Asia (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1985), 36–37, 39. (From National Library, Singapore, Call no. RSING 382.0959 HAL) ↩

-

Alastair Lamb, “Indian Influence in Ancient Southeast Asia,” in A Cultural History of India, ed. A.L. Basham (Delhi: Oxford University Press, 1985), 445. (From National Library, Singapore, Call no. R 954 CUL) ↩

-

Reinecke, Laychou and Seng, First Golden Age of Cambodia, 155. The site of Sanxingdui (三星堆) in the Sichuan basin, which is thought to date from the 11th to 12th century BCE, for example, has uncovered pits that contained spectacular gold masks. See Gideon Shelach-Lavi, The Archaeology of Early China: From Prehistory to the Han Dynasty (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2015), 242–46. (From National Library, Singapore, Call no. R 931 SHE) ↩

-

Rouletted ware usually refers to a “flat-based shallow dish about 6 centimetres (cm) deep and up to 32 cm in diameter, with an incurved bevelled rim. Decoration comprises one or three interior bands of impressed rouletted designs on the base of the dish or pot [and based on ceramics analysis at the archaeological excavation site of Tissamaharama]. Rouletted Ware first emerged in the 3rd and 2nd centuries BCE and belongs to a group of pottery that has been found at archaeological sites along the east coast of India to the Tamil coast and farther south to Sri Lanka.” See Himanshu Prabha Ray, “Culture, the Written Word, and the Sea, 3rd Century BCE to 4th Century CE,” in Coastal Shrines and Transnational Maritime Networks Across India and Southeast Asia (London: Routledge, 2021), 25–27. (From National Library, Singapore, Call no. RSEA 294.3435095409146 RAY) ↩

-

Dorian Q. Fuller, et al., “Across the Indian Ocean: The Prehistoric Movement of Plants and Animals,” Antiquity 85, no. 328 (June 2011): 544–58. (From ProQuest Central via NLB’s eResources website); Ray, “Culture, the Written Word, and the Sea, 3rd Century BCE to 4th Century CE,” 21–53. ↩

-

Abū Zayd al-Sīrāfī, Accounts of China and India: Lively Depictions of the Natural Life, Peoples, and Kingdoms Around the Indian Ocean, trans. Tim Mackintosh-Smith (New York: New York University Press, 2017), 43–44. (From National Library, Singapore, Call no. R 915.104 SIR-[TRA]) (Abū Zayd al-Sīrāfī was a seafarer who moved from the Persian port-city of Siraf to Basra.) ↩

-

Abū Zayd al-Sīrāfī, Accounts of China and India, 43–44. ↩

-

Abū Zayd al-Sīrāfī, Accounts of China and India, 43–44. ↩

-

Wang Dayuan was a Yuan dynasty traveller known for his two ship voyages. For a study of his writings relating to Singapore, see Miksic, Singapore & the Silk Road of the Sea, 169–79. ↩

-

Fei Xin was a soldier who served under Ming dynasty Admiral Zheng He. ↩

-

W.W. Rockhill, “Notes on the Relations and Trade of China with the Eastern Archipelago and the Coast of the Indian Ocean during the Fourteenth Century. Part II,” T’oung Pao 16, no. 1 (March 1915): 61–159. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website) ↩

-

Rockhill, “Notes on the Relations and Trade of China,” 105–107. ↩

-

David Killick and Thomas Fenn, “Archaeometallurgy: The Study of Pre-industrial Mining and Metallurgy,” Annual Review of Anthropology 41 (2012): 562–63. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website) ↩

-

Praveena Gullapalli, “Early Metal in South India: Copper and Iron in Megalithic Contexts,” Journal of World Prehistory 22, no. 4 (December 2009): 439–59; Upendra Thakur, “Source of Gold for Early Coins of India,” East and West, 30, no. 1/4 (December 1980): 99–115. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website) ↩

-

Jianjun Mei, et al., “Archaeometallurgical Studies in China: Some Recent Developments and Challenging Issues,” Journal of Archaeological Science 56 (February 2015): 227–28, ResearchGate, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/272846438_Archaeometallurgical_Studies_in_China_Some_Recent_Developments_and_Challenging_Issues. ↩

-

Thomas Oliver Pryce, Bérénice Bellina-Pryce and Anna T.N. Bennett, “The Development of Metal Technologies in the Upper Thai-Malay Peninsula: Initial Interpretation of the Archaeometallurgical Evidence from Khao Sam Kaeo,” Bulletin de l’École Francaise d’Extrême-Orient 93 (2006): 308–11; Michele H.S. Demandt, “Early Gold Ornaments of Southeast Asia: Production, Trade, and Consumption,” Asian Perspectives 54, no. 2 (Fall 2015): 323. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website) ↩

-

Pryce, Pryce and Bennett, “Development of Metal Technologies in the Upper Thai-Malay Peninsula,” 308; Killick and Fenn, “Archaeometallurgy,” 563; Paul T. Craddock, Early Metal Mining and Production (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1995), 23–87. (Not available in NLB holdings); Bennet Bronson and Pisit Charoenwongsa, Eye Witness Accounts of the Early Mining and Smelting of Metals in Mainland Southeast Asia (Bangkok: Thailand Academic Publishing Co., 1985). (From National Library, Singapore, Call no. RSEA 338.2740959 BRO) ↩

-

Moh. Ali Fadillah, “Industri Emas di Kotawaringin: Kasus Strategi Ekonomi,” in Metalurgi Dalam Arkeologi: Proceedings - Analisis Hasil Penelitian Arkeologi IV, Kuningan, 10–16 September 1991 (Jakarta: Pusat Penelitian Arkeologi Nasional, Departemen Pendidikan dan Kebudayaan, 1993), 251–55, Repositori Institusi Kementrian Pendidikan dan Kebudayaan, http://repositori.kemdikbud.go.id/3935/. ↩

-

Anna T.N. Bennett, “Gold in Early Southeast Asia,” ArchaeoSciences 33 (2009): 99–107, OpenEditions Journal, https://journals.openedition.org/archeosciences/2072; Nicholas N. Dodge, “Mineral Production on the East Coast of Malaya in the Nineteenth Century,” Journal of the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society 50, no. 2 (232) (1977): 92. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website) ↩

-

The ethnic Karo traditionally live in the North Sumatra and Aceh provinces of Sumatra. ↩

-

J.E. Jasper and Mas Pirngadie, “De Goud-en Zilversmeedkunst,” in De Inlandsche Kunstnijverheid in Nederlandsch Indië, vol. 4 (s-Gravenhage: Mouton & Co., 1927): 26, Leiden University Libraries Digital Collections, http://hdl.handle.net/1887.1/item:1086942 ; T.M. Hari Lelono, “Tradisi Alat Logam Bagi Masyarakat Jawa (Kajian Awal Ethnoarkeologi),” in Metalurgi Dalam Arkeologi: Proceedings – Analisis Hasil Penelitian Arkeologi IV, Kuningan, 10–16 September 1991 (Jakarta: Pusat Penelitian Arkeologi Nasional, Departemen Pendidikan dan Kebudayaan, 1993), 393–95, Repositori Institusi Kementrian Pendidikan dan Kebudayaan, http://repositori.kemdikbud.go.id/3935/. ↩

-

Stanley J. O’Connor, “Metallurgy and Immortality at Candi Sukuh, Central Java,” Indonesia, no. 39 (April 1985): 52–70. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website); Stanley J. O’Connor, “Ritual Deposit Boxes in Southeast Asian Sanctuaries.” Artibus Asiae 28, no. 1 (1966): 53–60. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website) ↩

-

Titi Surti Nastiti, “Pandai Logam Dalam Kehidupan Masyarakat Jawa Kuno,” in Metalurgi dalam Arkeologi: Proceedings – Analisis Hasil Penelitian Arkeologi IV, Kuningan, 10–16 September 1991 (Jakarta: Pusat Penelitian Arkeologi Nasional, Departemen Pendidikan dan Kebudayaan, 1993), 274–75; Made Geria, “Kerajinan Logam pada Masa Bali Kuno di Bali,” in Metalurgi dalam Arkeologi: Proceedings – Analisis Hasil Penelitian Arkeologi IV, Kuningan, 10–16 September 1991 (Jakarta: Pusat Penelitian Arkeologi Nasional, Departemen Pendidikan dan Kebudayaan, 1993), 381, Repositori Institusi Kementrian Pendidikan dan Kebudayaan, http://repositori.kemdikbud.go.id/3935/. ↩

-

T.O. Pryce, et al., “Intensive Archaeological Survey in Southeast Asia: Methodological and Metallurgical Insights from Khao Sai On, Central Thailand,” Asian Perspectives 50, no. 1/2 (Spring/Fall 2011): 57–61. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website); Mai Lin Tjoa-Bonatz, ed., A View from the Highlands: Archaeology and Settlement History of West Sumatra, Indonesia. (Singapore: ISEAS Publishing, 2020), 72–74. (From National Library, Singapore, Call no. RSEA 959.81 VIE) ↩

-

Demandt, “Early Gold Ornaments of Southeast Asia,” 306, 319. ↩

-

Ambra Calo, et al., “Trans-Asiatic Exchange of Glass, Gold and Bronze: Analysis of Finds from the Late Prehistoric Pangkung Paruk Site,” Antiquity 94, no. 373 (February 2020), 119. (From ProQuest Central via NLB’s eResources website) ↩

-

The Majapahit empire, founded in 1294 CE, was based in East Java. Singapore was said to be a vassal state of Majapahit. See Miksic, Singapore & the Silk Road of the Sea: 1300–1800, 185. ↩

-

Wang Dayuan (汪大渊) mentions an attack by Siam around 1330 CE, when the Siamese were trying to establish influence in the area. According to a text called the Pararaton, Majapahit military leader Gajah Mada is said to have made an oath to conquer a list of places in the Nusantara region (maritime Southeast Asia). Temasek is mentioned in the list. According to the Nagarakrtagama text dated approximately 1365 CE, Gajah Mada was successful in achieving his oath. See Miksic, Singapore & the Silk Road of the Sea: 1300-1800, 163, 185. ↩

-

“Treasure Trove: Discovery at Fort Canning,” Singapore Free Press, 19 July 1928, 9. (From NewspaperSG); Richard O. Winstedt, “Gold Ornaments Dug Up at Fort Canning, Singapore,” Journal of the Malayan Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society 6, no. 4 (105) (November 1928): 1–4. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website); John N. Miksic, Archaeological Research on the “Forbidden Hill” of Singapore: Excavations at Fort Canning, 1984 (Singapore: National Museum Singapore, 1985), 42–47. (From National Library, Singapore, Call no. RSING 959.57 MIK-[HIS]); Shah Alam Zaini, “Metal Finds and Metal-Working at the Parliament House Complex, Singapore,” (master’s thesis, Michigan University, 1997), 7, http://hdl.handle.net/2027.42/149090. ↩

-

“Japs Took Ancient Ornaments,” Straits Times, 6 March 1948, 4. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

A decorative pattern with the face of kāla. Kāla is a Hindu deity often synonymous with death, but kāla is also associated with the passing of time. See W.J. Johnson, “Kāla,” in A Dictionary of Hinduism (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010), 163. (From National Library, Singapore, Call no. R 294.503 JOH) ↩

-

A Hindu-Buddhist deity more popularly found in Indian and Tibetan traditions, the Mahākāla is a “frequent epithet of Śiva, either in his role as the destroyer of the universe at the end of a cosmological cycle, and therefore lord of death […] or in his soteorological role as the conqueror of both time and death”. See Johnson, “Kāla,” 163. For more, see Kurt Behrendt. “Tibet and India: Buddhist Traditions and Transformations,” Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin 71, no. 3 (Winter, 2014): 37–39. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/metpublications/Tibet_and_India_Buddhist_Traditions_and_Transformations. ↩

-

Iskandar Mydin and Sharon Lim, “Towards a Shared History: The Hill and the Malay Archipelago,” Cultural Connections 3, (2018): 113–16, Culture Academy Singapore, https://www.mccy.gov.sg/cultureacademy/researchandpublications/journals/Cultural-Connections-Vol-3; Claudine Bautze-Picron, “History of Padang Lawas, North Sumatra. II: Societies of Padang Lawas (Mid-Ninth-Thirteenth Century CE),” Archipel 43 (2014), 107–28, note 30, Academia, https://www.academia.edu/43979062/Bautze_Picron_2014_Buddhist_Images_from_Padang_Lawas; Mai Lin Tjoa-Bonatz, ed., “Early Histories: Historiography and Archaeological Surveys,” in A View from the Highlands: Archaeology and Settlement History of West Sumatra, Indonesia (Singapore: ISEAS Publishing, 2020), 39, 41. (From National Library, Singapore, Call no. RSEA 959.81 VIE); Maud Girard-Geslan and Martowikrido Wahyona, Indonesian Gold: Treasures from the National Museum, Jakarta (Queensland: Queensland Art Gallery, 2003), 82–83. (Not available in NLB holdings) ↩

-

Abdul Hadhi, “Gold in S’pore? Definitely No!,” New Paper, 10 December 1988, 8. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Mai Lin Tjoa-Bonatz and Nicole Lockhoff, “Java: Arts and Representations. Art Historical and Archaeometric Analyses of Ancient Jewellery (7–16th C.): The Prillwitz Collection of Javanese Gold,” Archipel 97 (June 2019): 19–68, OpenEdition Journals, https://journals.openedition.org/archipel/1018. ↩

-

Rohaniah Saini, “Exciting 14th-Century Relics in Fort Canning Find,” Straits Times, 31 March 1990, 3. (From NewspaperSG); Shah Alam Zaini, “Metal Finds and Metal-Working, 31–32; Brigitte Borell, “Money in 14th Century Singapore,” in Southeast Asian Archaeology 1998: Proceedings of the 7th International Conference of the European Association of Southeast Asian Archaeologists, Berlin, 31 August – 4 September 1998, ed. Wibke Lobo and Stefanie Reimann (Hull: Centre for Southeast Asian Studies, University of Hull, 2000), 11–12. (Not available in NLB holdings); Lim Chen Sian, Preliminary Report on the Archaeological Investigations at the National Gallery Singapore, Nalanda-Sriwijaya Centre Archaeology Unit Archaeology Report Series 5 (Singapore: Nalanda-Sriwijaya Centre, ISEAS - Yusof Ishak Institute, 2017), 63. (From National Library, Singapore, Call no. RSING 959.5703 LIM-[HIS]) ↩

-

Borell, “Money in 14th Century Singapore,” 11–12. ↩

-

Lien Dwiari Ratnawati, “Kelompok Pembuat Perhiasan pada masa Jawa Kuna: Data Prasasti Masa Kayuwangi-Balitung,” in Metalurgi dalam Arkeologi: Proceedings - Analisis Hasil Penelitian Arkeologi IV, Kuningan, 10–16 September 1991 (Jakarta: Pusat Penelitian Arkeologi Nasional, Departemen Pendidikan dan Kebudayaan, 1993), 225–34, Repositori Institusi Kementrian Pendidikan dan Kebudayaan, http://repositori.kemdikbud.go.id/3935/. ↩

-

Jan Wisseman Christie, “Money and its Uses in the Javanese States of the Ninth to Fifteenth Centuries A.D.,” Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient 39, no. 3 (1996): 243–86. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website) ↩

-

The Chinese sources that mention this are Wang Dayuan’s (汪大渊) A Brief Account of Island Barbarians (島夷志略; Dao Yi Zhi Lue, dated 1349 CE) and Feixin’s (费信) The Overall Survey of the Star Raft (星槎勝覽; Xing Cha Sheng Lan, dated 1436 CE). See Rockhill, “Notes on the Relations and Trade of China,” 129–32; see also John N. Miksic and Geok Yian Goh, Ancient Southeast Asia (London: Routledge, 2017), 177–78, 502. (From National Library, Singapore, Call no. RSEA 959.01 MIK) ↩

-

Miksic, Archaeological Research on the “Forbidden Hill” of Singapore, 68–71, 77, 88; Sharon Wai-yee Wong, “A Case Report on the Function(s) of the ‘Mercury Jar’: Fort Canning, Singapore, in the 14th Century,” Archaeological Research in Asia 7 (2016): 10–17, Academia, https://www.academia.edu/28401760/A_Case_Report_on_the_Function_s_of_the_Mercury_Jar_Fort_Canning_Singapore_in_the_14th_Century_Archaeological_Research_in_Asia_2016_7_10_17. Mined gold was said to be treated with lead in the 4th century BCE to help recover gold from ores and lead was later replaced by the use of mercury in the 10th century CE. See Craddock, Early Metal Mining, 114–15; R.P. Kangle, The Kautilīya Arthaśāstra Part II: An English Translation with Critical and Explanatory Notes (Bombay: Bombay University Press, 1963), 127, Internet Archive, https://archive.org/details/kautiliyaarthasastrakangaler.p.vol2/page/n9/mode/2up. ↩

-

Sogdians are an “Iranian people whose homeland is located in present-day Uzbekistan and Tajikstan”. See Judith A. Lerner and Thomas Wide, “Who were the Sogdians, and Why Do They Matter?,” Freer Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, accessed 10 August 2021, https://sogdians.si.edu/introduction/. ↩

-

Qi Dongfang, “Gold and Silver on the Tang Shipwreck,” in Shipwrecked: Tang Treasures and Monsoon Winds, ed. Regina Krahl, et al. (Singapore: Singapore Tourism Board and National Heritage Board, 2010), 221–27. (From National Library, Singapore, Call no. RSING 910.916474 SHI); Kwa Chong Guan, “Locating Singapore on the Maritime Silk Road: Evidence from Maritime Archaeology, Ninth to Early Nineteenth Centuries,” in Marine Archaeology in Southeast Asia: Innovation and Adaptation, ed. Heidi Tan (Singapore: Asian Civilisations Museum, 2012), 15–51. (From National Library, Singapore, Call no. RSING 930.102804 MAR); Roxanna M. Brown, “History of Shipwreck Excavation in Southeast Asia,” in The Belitung Wreck: Sunken Treasures from Tang China, ed. Jayne Ward, Zoi Kotitsa and Alessandra D’Angelo (New Zealand: Seabed Explorations, 2004), ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute, https://www.iseas.edu.sg/centres/nalanda-sriwijaya-centre/research-tools/compilations/the-belitung-wreck-sunken-treasures-from-tang-china; Natali Pearson, “Protecting and Preserving Underwater Cultural Heritage in Southeast Asia,” in The Palgrave Handbook on Art Crime, ed. Saskia Hufnagel and Duncan Chappell (London: Palgrave Macmillan UK, 2019). (Not available in NLB holdings) ↩

-

Michael Armand P. Canilao, Remote Sensing the Margins of the Gold Trade: Ethnohistorical and GIS Analysis of Five Gold Trade Networks in Luzon, Philippines, in the Last Millennium BP (Oxford: BAR Publishing, 2020). (From National Library, Singapore, Call no. RSEA 305.80095991 CAN) ↩