Negotiating Boundaries: Japanese and Chinese Photo Studios in Prewar Singapore

Photo studios such Yong Fong, Lee Brothers and Daguerre had to negotiate the politics of race, class and clan.

By Zhuang Wubin

In the 19th century, British and European firms such as Sachtler & Co. and G.R. Lambert & Co. dominated the photography business in Singapore and Malaya. But by the onset of the 20th century, Chinese and Japanese practitioners had made their presence felt in the trade. At the time, there were visible and invisible lines segregating the colonial society according to social class, race, ethnicity and dialect group. These dividing lines, in turn, affected those who worked in the photographic trade or patronised the photo studios, requiring them to negotiate these boundaries according to evolving situations.

Mapping Japanese Studios

According to a 1910 census by the Japanese government, there were 1,215 Japanese residents in Singapore. The community operated three photographic businesses that involved seven men and six women.1 A 1917 publication, 馬來に於ける邦人活動の現況 (Marai ni okeru hōjin katsudō no genkyō; Current Status of the Activities of the Japanese in Malaya), included a listing of Japanese businesses in Malaya, with eight separate entries relating to the photographic trade in Singapore. Four were photo studios while two other entries each listed an individual photographer, one with the “specialisation of going out to photograph”. It is possible that both photographers also maintained a photo studio each. The remaining two entries were traders of photographic supplies and equipment.2

Many of these Japanese businesses were located within the vicinity of what founding principal of Raffles Junior College, Rudolf (Rudy) William Mosbergen, had called “Little Japan” in Singapore, using it to highlight the Japanese presence along Middle Road, Queen Street, Prinsep Street and Selegie Road.3

Growing up on Queen Street, Mosbergen was neighbours with some of them, but did not mingle much. “There was no relationship because first, I didn’t speak Japanese. And they were very insular people – they didn’t mix very much with us,” he said. Mosbergen also recalled several photo studios along Middle Road and North Bridge Road, including some very good Japanese ones. He still owned a photo taken by one such studio.4

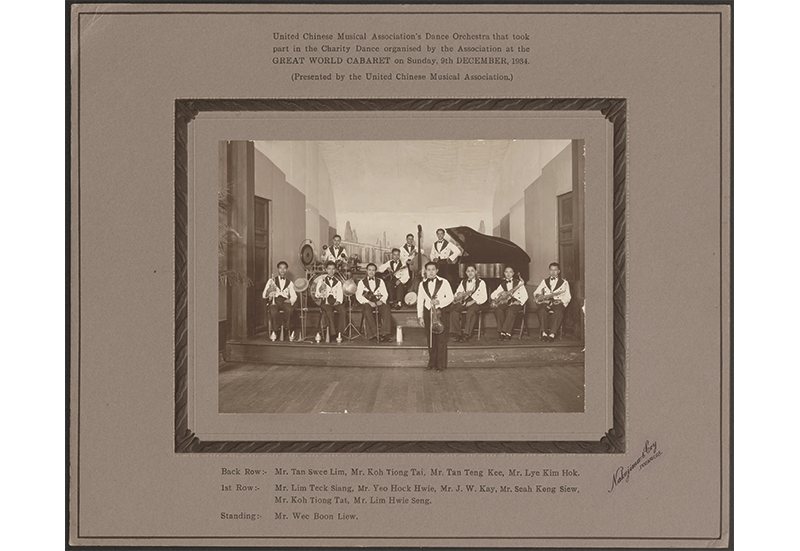

In the decades prior to World War II, nearly every town in Malaya had at least one Japanese studio. In Singapore, Nakajima & Co., established by S. Nakajima, was the most famous Japanese-owned studio then and was active at least since the start of the 1920s. The Malaya Tribune described it as “the best of the photographic establishments in Singapore”.5

Headquartered in Kuala Lumpur, an advertisement in the Straits Times in 1923 indicated that the studio had opened a branch on Orchard Road in Singapore. It offered the services of “developing, printing, enlarging for amateurs”, and provided outdoor photography for prospective clients. Besides the sale of photographic supplies such as film and glass plates, Nakajima & Co. also offered postcards and views of Malaya.6

Nakajima’s photographs had earlier appeared in the souvenir guide of the Malaya Borneo Exhibition, the colonial spectacle held in Singapore in 1922.7 His contributions include, among others, a photograph of the Orang Asli, or aborigines, of the Malay Peninsula using their blowpipes and an image of locals weaving sarong.

Nakajima’s photographs added an exotic touch to the souvenir guide. Perhaps unintentionally, these photographs visualised the logic of colonial exploitation, which necessitated the organisation of the colonial fair in the first place. It is also possible that Nakajima’s involvement in the fair facilitated his entry into Singapore. The studio was already well embedded within the colonial society in the 1920s. By the end of 1923, it had moved to a choice location: a unit at Raffles Hotel, fronting Bras Basah Road.8

Nakajima & Co. was often commissioned to take photographs of social functions and weddings, usually of the European community in Singapore. Many of these photographs were also published in the English newspapers of the time. Prior to the specialisation of press photography, photo studios were an important source of photographs for the press. Throughout the 1930s, the studio was also frequently mentioned in the press during the Christmas festive season as the go-to place for photographic gifts.9

Chinese Studios and the Cantonese Dominance

According to a Chinese-language directory, 新加坡各业调查 [Survey of Singapore’s Different Industries], published in 1928, there were 18 Chinese-owned photo studios in Singapore at the time. There were also four Chinese companies in 1922 dealing in photographic supplies and materials.10

In the first half of the 20th century, the Chinese photographic trade was dominated mainly by the Cantonese.11 Like other Chinese businesses, the proprietors of photo studios tended to hire relatives as well as people from the same dialect group. The owners would zealously guard photographic knowhow and would not readily divulge their trade secrets to outsiders.

In 1935, a young and motivated Wong Ken Foo (more popularly known as K.F. Wong; 1916–98), who was born in Sibu, Sarawak, arrived in Singapore.12 He had set his eyes on Brilliant Studio on South Bridge Road and offered to work as an apprentice for three years without pay. His offer was rejected, ostensibly because Wong was of Henghua descent while the studio was owned by a prominent Cantonese.13 (Wong subsequently became famous for his photographs of the indigenous Dayak peoples of Sarawak.14)

David Ng Shin Chong (b. 1919, Singapore), a Hakka photographer who began his apprenticeship in the photographic trade in 1938, noted that “[t]he situation in the past was different. Everyone [photo studio owners] was more selfish, secretive”.15

One of the most famous Cantonese photo studios in Singapore was the Lee Brothers Studio, established by Lee King Yan (1877–1957) and Lee Poh Yan (1884–1960). The brothers were part of the extended Lee family, who was originally from the Nanhai district in Guangdong province. Much has been written about the chain of photo studios that the family had opened in Singapore, Malaya and Java. In Singapore, the family was responsible for establishing Yong Fong, Lee Brothers and Eastern Studio, among others.16

Lee Shui Loon (1864–1935), also known as Lee Yin Fun, was the most senior member of the family to sink roots locally, prompting art historian Daphne Ang to call him the “godfather of photography in Singapore”.17 He established Yong Fong, which was active as early as 1908, along South Bridge Road, just across from Mosque Street.18

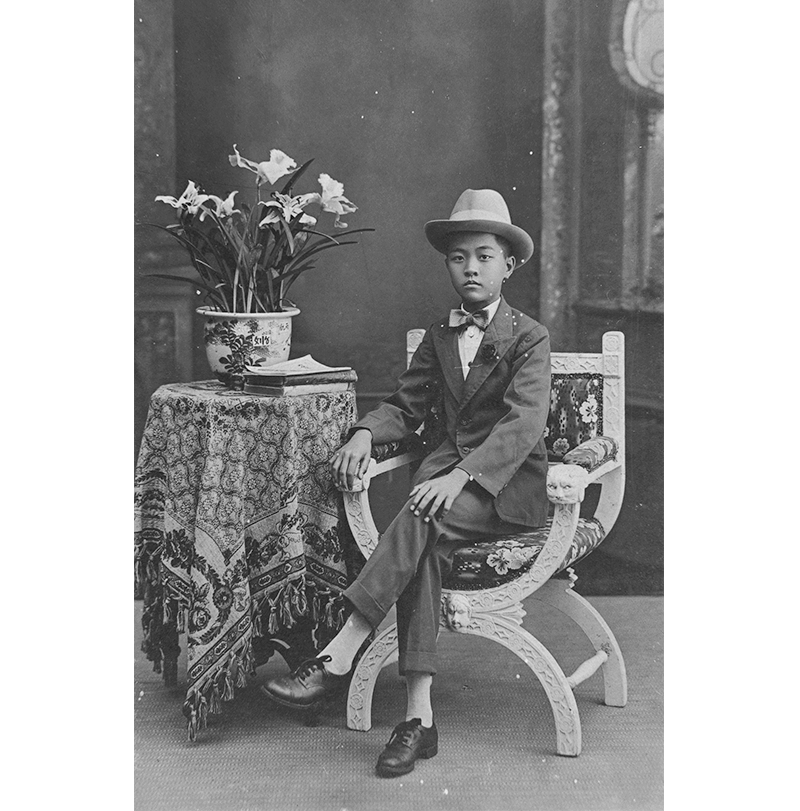

Lee Shui Loon’s nephews, Lee King Yan and Lee Poh Yan, who set up Lee Brothers, were effectively bilingual, speaking Cantonese at home and using English, if necessary, at work.19 Their command of English enabled them to serve a different class of clientele by setting up shop on Hill Street, in the business district in around 1908.20 Soon after, Lee Brothers became “one of the most expensive studios in Singapore”.21

Beyond the network of photo studios that the Lee family had established, there were other Cantonese-owned studios catering to clients across the economic spectrum. However, the division among dialect groups seemed to discourage certain Chinese customers from patronising Cantonese studios.

Former bank manager Wong Kum Fatt (b. 1925, Singapore) grew up in his adopted uncle’s photo studio off South Bridge Road and Spring Street. The studio was located on the Cantonese side of the Chinese quarter, with the Hokkiens generally occupying the area across South Bridge Road, towards Telok Ayer Street.

Despite the studio’s proximity to the Hokkien community, it was frequented mostly by Indian and Cantonese customers. Said Wong in his oral history interview in 1984: “Usually Hokkien they will not come and patronise a Cantonese shop at that period… At that time the Cantonese they will only go to the Cantonese shop, eat… Cantonese food.”22

It is unlikely that these divisions were strictly observed in practice, especially among non-Cantonese customers at the lower end of the economic spectrum. If people needed to have their formal portraits taken, they would inevitably have to patronise the Cantonese studios, unlike more affluent customers who enjoyed the luxury of choice.

Some aspiring non-Cantonese photographers managed to enter the trade despite the barriers of dialect and family.23 David Ng Shin Chong, the Hakka photographer mentioned previously, started out as an apprentice at Natural Studio on North Bridge Road. The studio was owned by a Cantonese-Teochew couple. Since it was located within the Hainanese enclave, they had a lot of Hainanese customers although people from other dialect groups also patronised the studio.24 By 1939, Ng had joined the Cantonese-owned Fee Fee Photographic Store, which traded in photographic supplies and provided developing and printing services.

A Hainanese Lineage

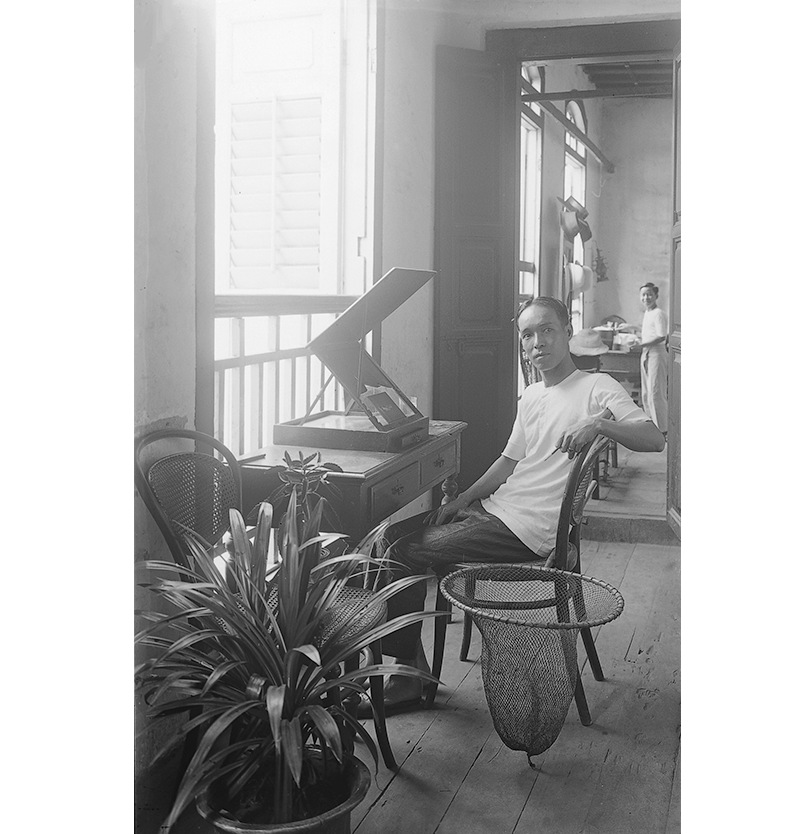

Daguerre Studio was the first Hainanese-owned studio to open in Singapore during the 20th century. The studio was established by Lim Ming Joon (c. 1904–91, b. Hainan) around 1931 and was named after the French artist and photographer Louis Daguerre, who invented the daguerreotype process of photography.25

Lim worked as a cook for almost a decade before becoming a photographer. One of his employers, an Armenian, had given him his first camera and for the next few years, Lim taught himself photography through reading and practice, using his savings to upgrade his equipment. By the time Lim thought of opening a studio, he had already bought a second-hand camera for $80 from Eastern Studio (established by Lee King Yan in 1922) and taken some wedding photos for his friends. At the time, there was a Japanese photographer who owned a studio in Katong. Lim wanted to be his apprentice, but the owner required him to pay a monthly fee of $15. The fee was too steep, and Lim attempted to bargain with him. The owner then asked to see his camera, prints and negatives. After inspecting his work, the owner was suitably impressed and allowed Lim to be his apprentice for free. For the next three to four months, Lim would go to the studio from around 1 pm to 3 pm each day while juggling his work as a cook.26

Lim could communicate with the Japanese photographer because both of them spoke Malay.27 Later on, when Lim expressed his intention to open his own studio, the Japanese even helped him design and install the lights for free. (It was not possible to buy readymade lights at the time.28)

Lim’s photo studio tapped into the broader Hainanese network of cultural ties, kinship and business interests to facilitate its existence and survival. It was initially sited within the premises of China Book Company on North Bridge Road, which was owned by four Hainanese brothers from the Foo family.29 The bookstore was located in the area where the majority of the Hainanese lived, worked and congregated, overlapping Little Japan. Middle Road, for instance, was colloquially known to the Chinese as “Hainan first street”.

Business picked up quickly and in less than a year, Daguerre Studio moved to a third-floor unit along Middle Road. One day, an aged Japanese photographer turned up at the studio. Apparently, he used to rent the same unit to run his studio and was curious to find out who had taken over the space. Over time, the two men became good friends.

Although he had largely retired from the profession, the Japanese photographer still had a contract with the Police Depot off Thomson Road. Hence, whenever he needed to replenish his glass plate negatives, he would buy these from Daguerre. Later, when he realised that the Japanese invasion was imminent, he gave the police contract to Lim and tried to leave Singapore. However, he was arrested by the British authorities and exiled to India.30

Daguerre Studio was opened from 8 am to 9 pm daily. Lim was the main photographer and he had four people working with him, including a darkroom specialist and a retoucher.31 They were all Hainanese and related to one another in terms of family or clan.32

Lim started taking in Hainanese apprentices, introduced by his relatives and friends. His nephew Lim Tow Tuan (b. 1916 in Hainan) arrived in Singapore in 1941 to work as an unpaid apprentice.33 According to Lim Ming Joon, his former employees and apprentices subsequently went on to open eight photo studios in Singapore, Johor Bahru, Brunei and North Borneo.34

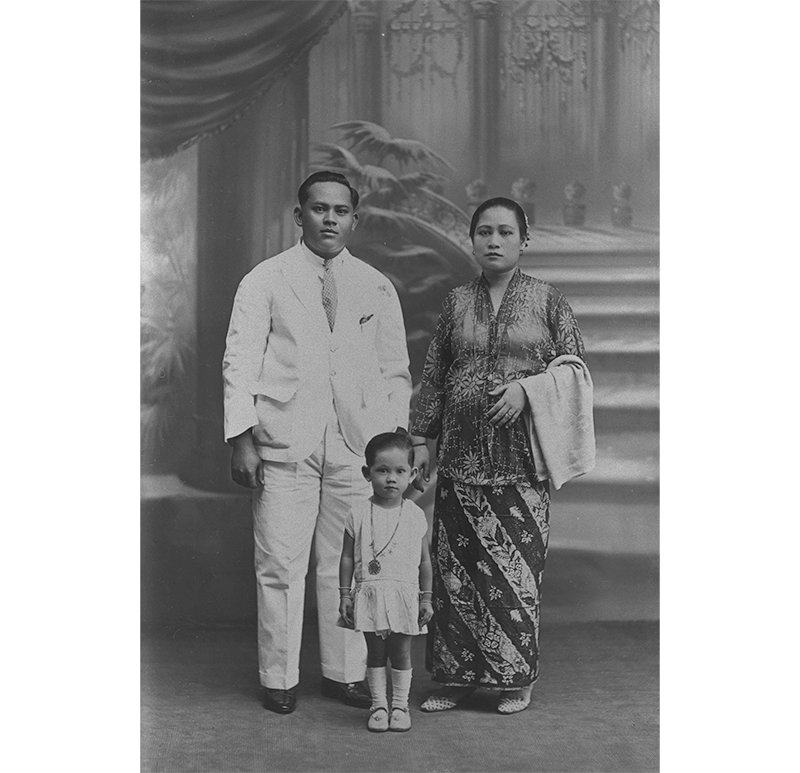

In the early days, the overwhelming majority of Daguerre’s customers were Hainanese,35 although there were also some Malay, Indian and British patrons.

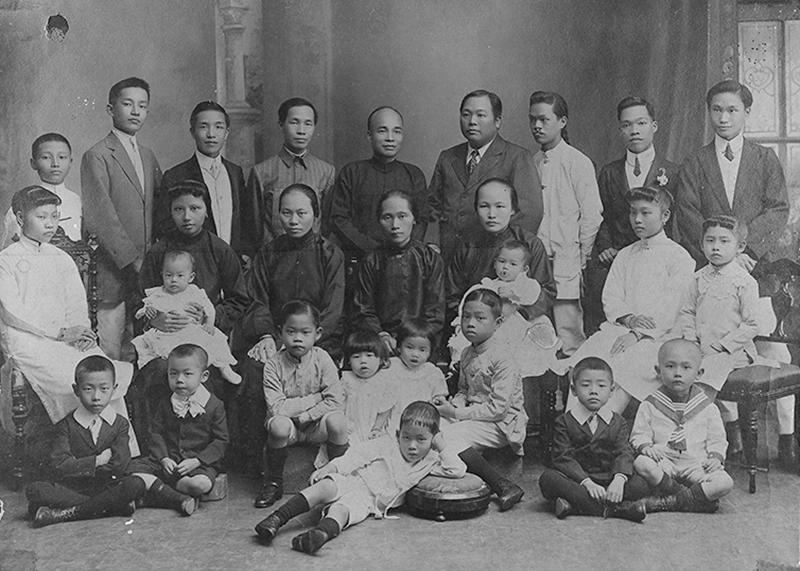

The Chinese customers were mainly from the working class who liked to take pictures to send home to China. They would usually come in their Sunday best. If they were unprepared, Lim would lend them suits and neckties. The studio also prepared spectacles without lenses for customers who wanted to look more serious in their portraits. Lim and his customers were clearly mindful of the impression that these photos would have on loved ones in China. At the very least, the customers would not want to give the impression that they could not even afford nice clothes, having made the difficult decision to come to Singapore.36

Lim also took on wedding shoots. Before the war, the trend, at least for the Hainanese, was to host a banquet for family and friends at one of the many coffeeshops near the studio. Lim would take group pictures of the couple and the guests.37 Over time, Daguerre became well known for taking large group photos. These were often requested by schools, associations, guilds and unions, usually for the purpose of investiture, commemoration or graduation.

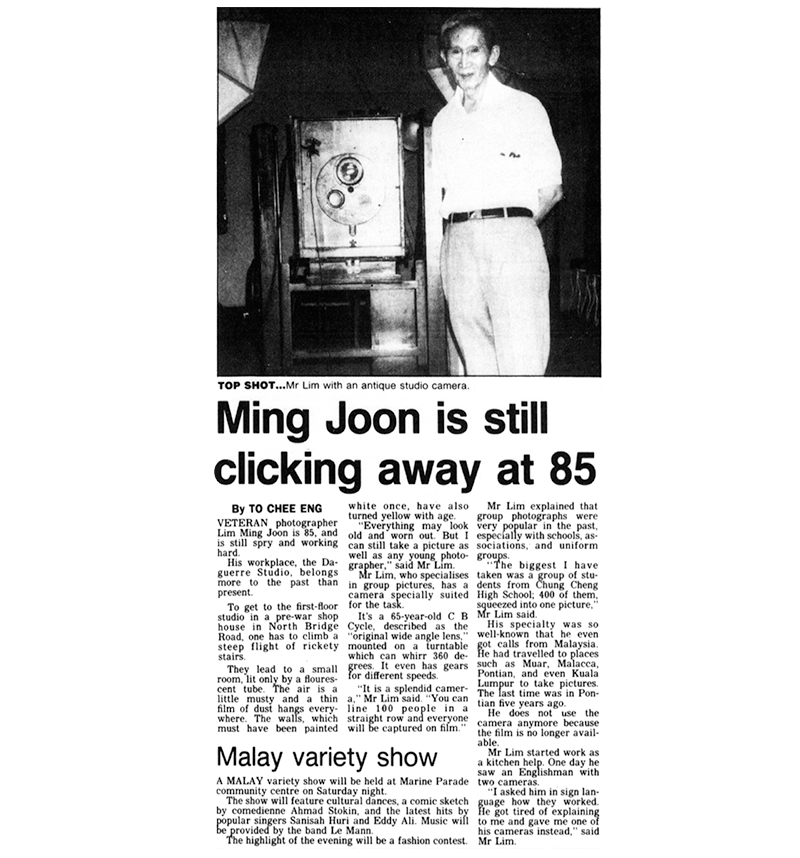

Lim began honing his expertise before the war, when camera technology made it challenging to photograph large groups of people. The biggest group that Lim had worked with occurred after the war when he was invited to photograph members of the Malaysian Chinese Association at a national meeting in Seremban, Malaya. Lim spent nearly one hour trying to position some 3,300 people.38

Lim was still working and taking pictures at large gatherings in the 1980s. In a 1983 interview with the Straits Times he said: “There are fewer group pictures of hundreds of people these days. But there are enough jobs in the studio and outdoors to keep me busy. Some of my old-time clients include ministers and members of Parliament. They are surprised to see me still turning up at community centres and other functions for group pictures.”39

The emergence of the Hainanese-owned Daguerre Studio marked the gradual loosening of Cantonese dominance in the photographic trade of Singapore. Its establishment was made possible, partly through the help of Japanese photographers. Soon, more Hainanese photo studios began opening. One reason for the survival and longevity of Chinese photo studios was the myriad of Chinese associations and institutions in Singapore and Malaya, which provided a constant source of work and revenue for these studios.

Heading to War

As Japan stepped up its aggression in China, the Chinese communities in Singapore and Malaya responded with a series of boycotts against Japanese businesses. In June 1938, a Chinese couple who had patronised a Japanese photo studio at Kuala Lipis, Pahang, was nearly attacked by those who heard the news.40 In Singapore, Lim Ming Joon contributed to the anti-Japanese movement by photographing the fundraising efforts and the rallies organised by the Chinese community.41

One day, the Japanese photographer who first helped Lim enter the trade came to see him. He knew it was time to leave Singapore but as he still had quite a lot of photographic equipment left, he hoped to sell these to Lim. Even though Lim considered the Japanese man his friend, he declined the offer. Lim knew that if the purchase was subsequently discovered, he would suffer the fate of having his ears cut off. In the end, Lim found a Peranakan (Straits Chinese) buyer for his old friend.42

By the end of 1941, the famous Nakajima & Co. in Singapore was forced to close down. The Malaya Tribune lamented its closure and commented that the “incident” (Japanese invasion) in China had “gradually weaned clients away from Japanese photographers”.43 On 8 December 1941, two days after the article was published, the first bombs fell on Singapore.

Zhuang Wubin is a writer, curator and artist. He has a PhD from the University of Westminster (London) and was a Lee Kong Chian Research Fellow (2017–18) at the National Library, Singapore. Wubin is interested in photography’s entanglements with modernity, colonialism, nationalism, the Cold War and “Chineseness”.

Zhuang Wubin is a writer, curator and artist. He has a PhD from the University of Westminster (London) and was a Lee Kong Chian Research Fellow (2017–18) at the National Library, Singapore. Wubin is interested in photography’s entanglements with modernity, colonialism, nationalism, the Cold War and “Chineseness”.NOTES

-

Regina Hong, Ling Xi Min and Naoko Shimazu, Postcard Impressions of Early 20th-century Singapore: Perspectives from the Japanese Community (Singapore: National Library Board, 2020), 115. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 959.57 HON-[HIS]) ↩

-

Mitsuharu Tsukuda, 馬來に於ける邦人活動の現況 (Marai ni okeru hōjin katsudō no genkyō) [Current Status of the Activities of the Japanese in Malaya] (Singapore: Nan’yō oyobi Nihonjinsha,1917), 37–48. (From Book SG; accession no. B29262852C). [Note: I would like to thank Mizuka Kimura and Miho Odaka for verifying my understanding of this source. This publication is part of the Lim Shao Bin Collection in the National Library, Singapore.] ↩

-

Rudy William Mosbergen, oral history interview by Pitt Kuan Wah, 19 September 2005, transcript and MP3 audio, Reel/Disc 1 of 7, 28:25, National Archives of Singapore (accession no. 002983), 3. ↩

-

Rudy William Mosbergen, interview, 19 Sep 2005, Reel/Disc 1 of 7, 2, 6. ↩

-

“Japanese Go Out of Business,” Malaya Tribune, 6 December 1941, 3. (From NewspaperSG); Daphne Ang Ming Li, “Constructing Singapore Art History: Portraiture and the Development of Painting and Photography in Colonial Singapore (1819–1959)” (PhD thesis, London, SOAS, University of London, 2017), 316, 393, https://eprints.soas.ac.uk/id/eprint/26662. ↩

-

“Page 13 Advertisements Column 1,” Straits Times, 21 February 1923, 13. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

For a brief introduction on the involvement of studio and amateur photographers in the Malaya Borneo Exhibition, see Zhuang Wubin, “Exhibiting Photography in Pre-war Singapore,” BiblioAsia 17, no. 3 (October–December 2021). ↩

-

“Page 16 Advertisements Column 1,” Straits Times, 24 November 1923, 16; “Page 5 Advertisements Column 3,” Malaya Tribune, 30 November 1923, 5. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Souvenir of Singapore,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 1 November 1932, 15; “A Christmas Shopping Guide,” Straits Times, 8 December 1935, 11; “A Christmas Shopping Guide,” Straits Times, 5 December 1937, 17. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

童子达 [Tong Zida], 新加坡各业调查 [Survey of Singapore’s Different Industries] (Singapore: The Chinese Industrial and Commercial Continuation School, 1928), 119. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RRARE 650.58 TTT; microfilm no. NL9586) ↩

-

李香南 [Li Xiangnan], 照相馆业广东人称雄 [“Cantonese Dominate the Photo Studio Business”], 联合早报 [Lianhe Zaobao], 22 March 1998, 46; 秦长春 [Qin Changchun], 新加坡照相业史话 [“A History of the Photographic Trade in Singapore”], 星洲日報 [Sin Chew Jit Poh], 7 July 1977, 16. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

For a detailed biography of K.F. Wong, see Zhuang Wubin, “From the Archives: The Work of Photographer K.F. Wong,” BiblioAsia 15, no. 2 (July–September 2019). ↩

-

房汉佳 [Fong Hon Kah] and 林韶华 [Lim Shau Hua], 世界著名摄影家黄杰夫 [World Famous Photographer K.F. Wong] (福州:海潮摄影艺术出版社, 1995), 25. ↩

-

Zhuang, “From the Archives: The Work of Photographer K.F. Wong.” ↩

-

David Ng Shin Chong, oral history interview by Ang Siew Ghim, 11 June 1986, transcript and MP3 audio, Reel/Disc 13 of 13, 28:50, National Archives of Singapore (accession no. 000670), 136. ↩

-

For a history of Lee Brothers Studio, see Gretchen Liu, “Portraits from the Lee Brothers Studio,” BiblioAsia 14, no. 1 (April–June 2018). [Note: In 1994, more than 2,500 excess or uncollected prints from Lee Brothers were donated to the National Archives of Singapore by Lee Hin Ming, the eldest son of Lee Poh Yan.] ↩

-

Ang, “Constructing Singapore Art History,” 240–41. ↩

-

Kiang Ai Kim (Mrs) @ Lee Peck Wan, oral history interview by Jesley Chua Chee Huan, 12 October 1995, MP3 audio, Reel/Disc 1 of 22, 30:10, National Archives of Singapore (accession no. 001698). ↩

-

It would be premature to discount, at this point, the possibility that Lee King Yan and Lee Poh Yan could also speak Malay. ↩

-

Lee Hin Meng, oral history interview by Irene Quah, 17 May 1994, MP3 audio, Reel/Disc 1 of 3, 29:51, National Archives of Singapore (accession no. 001487). ↩

-

Lee Hin Meng, interview, 17 May 1984, Reel/Disc 1 of 3. ↩

-

Wong Kum Fatt, oral history interview by Yao Souchou, 6 October 1984, transcript and MP3 audio, Reel/Disc 1 of 6, 27:56, National Archives of Singapore (accession no. 000474), 7. ↩

-

Elaine Chiew Peck Leng, “Self-Fashioning towards Modernity: Early Chinese Studio Photography of Chinese Women” (unpublished manuscript, 2021), PDF file. This manuscript is prepared for the fulfilment of the Singapore Chinese Cultural Centre grant. ↩

-

David Ng Shin Chong, oral history interview by Ang Siew Ghim, 27 May 1986, transcript and MP3 audio, Reel/Disc 4 of 13, 29:26, National Archives of Singapore (accession no. 000670), 37–38. ↩

-

韩山元 [Han Tan Juan], 如何为三千人拍照 [“How to Take a Photograph for Three Thousand People”], 联合晚报 [Lianhe Wanbao], 18 August 1986, 8. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Lim Ming Joon, oral history interview by Tan Beng Luan, 23 September 1983, transcript and MP3 audio, Reel/Disc 2 of 7, 28:07, National Archives of Singapore (accession no. 000334), 24–28; Lim Ming Joon, interview, 23 Sep 1983, Reel/Disc 3 of 7, 30–31. ↩

-

Lim Ming Joon, interview, 23 Sep 1983, Reel/Disc 3 of 7, 34. ↩

-

Lim Ming Joon, oral history interview by Tan Beng Luan, 30 September 1983, transcript and MP3 audio, Reel/Disc 1 of 7, 27:54, National Archives of Singapore (accession no. 000333), 5. ↩

-

Song Chin Sing, ed., Passage of Time: Singapore Bookstore Stories 1881–2016 (Singapore: Chou Sing Chu Foundation, 2016), 162–65. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 070.5095957 CHO) ↩

-

Lim Ming Joon, interview, 23 Sep 1983, Reel/Disc 3 of 7, 35. ↩

-

Lim Ming Joon, interview 23 Sep 1983, Reel/Disc 4 of 7, 44. ↩

-

Lim Ming Joon, oral history interview by Tan Beng Luan, 14 October 1983, transcript and MP3 audio, Reel/Disc 4 of 7, 27:38, National Archives of Singapore (accession no. 000333), 49. ↩

-

Lim Seng @ Lim Tow Tuan, oral history interview by Tan Beng Luan, 28 December 1983, transcript and MP3 audio, Reel/Disc 2 of 8, 27:53, National Archives of Singapore (accession no. 000089), 12–15. ↩

-

Lim Ming Joon, oral history interview by Tan Beng Luan, 11 November 1983, transcript and MP3 audio, Reel/Disc 7 of 7, 26:58, National Archives of Singapore (accession no. 000334), 82–84. ↩

-

莫美颜 [Mok Mei Ngan], 海南人最早的照相馆 [“The First Photo Studio of the Hainanese”], 联合早报 [Lianhe Zaobao], 15 February 1998, 42. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Lim Ming Joon, interview, 23 Sep 1983, Reel/Disc 3 of 7, 36–38, 40-41. ↩

-

Lim Ming Joon, interview, 23 Sep 1983, Reel/Disc 3 of 7, 36. ↩

-

王振春 [Wang Zhenchun], 话说密驼路 [Speaking of Middle Road] (Singapore: Xinhua Cultural Enterprises, 2021), 103. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. Chinese RSING 959.57 WZC-[HIS]); Han, 如何为三千人拍照. ↩

-

Teo Han Wue, “Lim’s in a World of His Own,” Straits Times, 20 June 1983, Section Three, 1. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

到敌人照相馆拍照 立卑一对男女几遭痛惩 [“A Couple at Lipis was Almost Severely Punished for Having Their Portrait Taken at the Enemy’s Photo Studio”], 南洋商报 [Nanyang Siang Pau], 26 June 1938, 10. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Lim Ming Joon, interview, 30 Sep 1983, Reel/Disc 1 of 7, 9. ↩

-

Lim Ming Joon, interview, 30 Sep 1983, Reel/Disc 1 of 7, 5. ↩