The Making of the Monetary Authority of Singapore: How the MAS Became Singapore’s Central Bank

While the Monetary Authority of Singapore was established in 1971, it only became a full-fledged central bank some 30 years later.

By Barbara Quek

“We are tired of being referred to as the de facto central bank all the time. Go ahead and call us the central bank henceforth,” an official from the Monetary Authority of Singapore (MAS) told the Straits Times in August 1998.1

It is a curious fact that for a little more than half its existence, the MAS, which was set up in 1971, was regularly referred to as Singapore’s de facto central bank. It was only in October 2002 that the MAS became the country’s official central bank following its merger with the Board of Commissioners of Currency, Singapore (BCCS). With the merger, the MAS was finally able to issue currency, the one major function it did not have when it was formed 51 years ago.

In September 1970, during the reading of the bill to set up MAS, then Finance Minister Hon Sui Sen explained that “as a result of historical factor, the various monetary functions normally associated with a central bank are currently being performed by a number of government departments”.2

At the time, while the Currency Board issued currency, the Commissioner of Banking and the Commissioner of Finance Companies were responsible for the regulation and supervision of banks and finance companies. The Exchange Control Department handled all foreign exchange matters, while the Department of Overseas Investment looked after the government’s external assets. Then there was the Accountant-General who was responsible for the sale of Treasury bills to banks and financial institutions, the raising of domestic loans and the management of the clearing house system.3

Hon’s predecessor at the Finance Ministry, Goh Keng Swee, described Singapore’s monetary system as “an untidy system of units that grew up ad hoc in course of time in response to urgent requirements”.4 To coordinate all the various departments, Goh would have weekly meetings with staff of the different departments on Monday mornings and additional meetings on Thursdays and Fridays if necessary.

To streamline the decision-making for such an important institution, it was logical that these different bodies should be brought together and in September 1970, the Monetary Authority of Singapore Bill was passed in Parliament.

Nonetheless, at the setting up of MAS, the ability to issue currency was deliberately left out. The BCCS was established in 1967 following Singapore’s separation from Malaysia in 1965, and the agreement that the two countries would issue their own separate currency. The role of the BCCS was to maintain the currency board system (practised since the colonial era) that “fixed the exchange rate between the Singapore dollar and a specified foreign currency, allowed domestic notes and coins to be fully convertible at the relevant fixed exchange rate, and backed the Singapore currency fully by foreign assets or gold”.5

Hon explained in his 1970 speech in Parliament that the BCCS was kept separate from MAS because the “automatic mechanism of the Currency Board with its 100 percent external assets backing has been and will be of great psychological importance in maintaining confidence in the Singapore dollar”.6

In the commemorative book published by MAS on its 40th anniversary in 2012, the writers explained that “the aim of keeping currency issuance separate from MAS was to assure Singaporeans and foreign investors that the central bank would not freely print money according to its whim. Instead, every Singapore dollar issued by BCCS would be fully backed by gold and foreign assets under the currency board system”.7

As Elizabeth Sam, then the chief manager of the Department of Investments and Exchange Control at the MAS, explained: “I think the whole objective was really confidence – that people would have confidence in a Singapore dollar that was one hundred percent backed by foreign reserves rather than this concept of a central bank with money creating capabilities.”8

Added Tang Wee Lip, then manager of the Banking Department at the MAS: “After the British colonial system began to pull back, there were several countries in Africa and Asia that became independent. At that time, a lot of African countries were also setting up central banks and some had a reputation of printing money. We didn’t want to fall into the same group.”9

Becoming a De Facto Central Bank

Although MAS did not have the ability to issue currency at its inception, there was a plan for it to eventually do so. As early as 1974 when the MAS was under the chairmanship of Hon, the government had given its in-principle approval for the MAS and the Currency Board to merge according to internal MAS documents.10

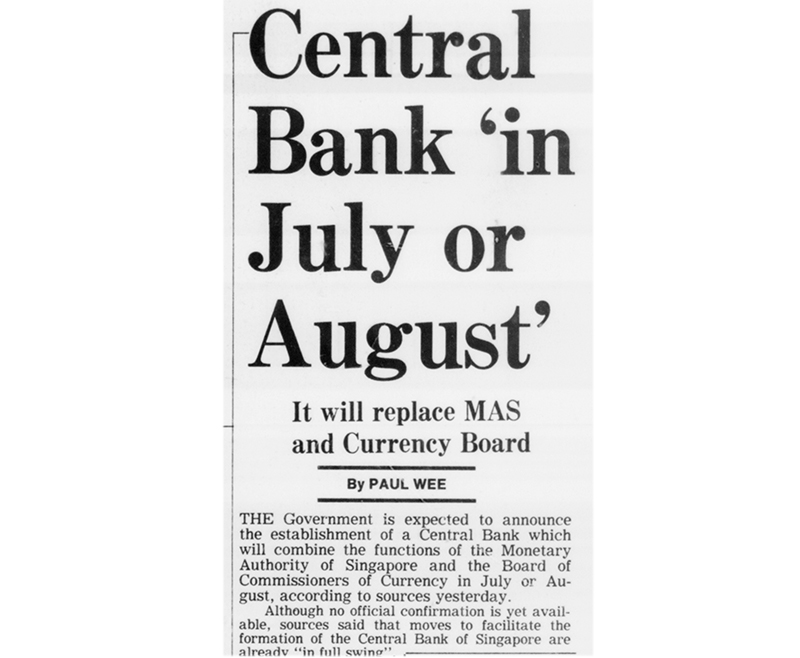

By the late 1970s, the newspapers were publishing stories about an impending merger. In May 1979, a front-page story in the Straits Times, citing unnamed sources, said that the government was expected to announce the establishment of a central bank in July or August that year and that this institution would combine the functions of the MAS and the BCCS. This did not come to pass and eventually, in October 1980, in another front-page story, the Straits Times reported that the central bank plan had been put off, pending a new appraisal.11

The plan to merge the two had been developed while Hon was chairman of both the MAS and BCCS. But when Goh succeeded Hon on 1 August 1980, Goh was against the idea of bringing the two institutions together.12

However, while Goh favoured the arrangement of using BCCS to issue currency, over time, the relevance of the separation was questioned. In October 2002, the MAS and the Currency Board finally became one entity.

Speaking in Parliament in July 2002 during the reading of a bill to amend the Currency Act to allow the merger, then Second Minister for Finance Lim Hng Kiang explained that when the Currency Board was set up in 1967, the system had three main features: the exchange rate was fixed between the domestic currency and a specified foreign currency, Singapore notes and coins were fully convertible at the fixed exchange rate, and the domestic currency was fully backed by gold or foreign assets.13

However since 1967, there had been a number of significant changes, Lim pointed out. Singapore had moved away from the fixed exchange rate after the currency was floated in 1973. And in 1982, the convertibility of domestic currency notes and coins into gold and other foreign currencies on demand was repealed. What then remained from the currency board system was that the currency in circulation would still be fully backed by external assets. This was required under the Currency Act and had contributed to confidence in the currency, he said, and this feature would not change after the merger.14

Lim also highlighted that in addition to being backed by external assets, confidence in the Singapore dollar exchange rate was “derived from the consistency and soundness of our monetary and fiscal policies, as well as our foreign reserves”. The merger, he said, would “enable us to rationalise common functions and realise efficiency gains, without compromising the overriding objective of managing the currency and maintaining confidence in the Singapore dollar. MAS will become a full-fledged central bank”.15

Behind the scenes, the move to merge the two institutions had picked up pace since the late 1990s. In 1997, in an exchange of letters with the BCCS, MAS raised the issue of whether the discipline of currency board was still relevant. While BCCS constrained the printing of physical currency, the government could issue bonds or use its foreign exchange reserves. The MAS also noted that confidence in the Singapore dollar was due to the country’s policies rather than the Currency Board. In addition, by 1997, the notes and coins in circulation made up less than 10 percent of the money supply. This meant the MAS had much more influence over the supply of money than the Currency Board did.16

These arguments undoubtedly formed part of the thinking to merge the two bodies. The wheels were set in motion to combine both institutions and after the necessary legislation was passed, the BCCS and the MAS became one in October 2002. The joint entity took on the latter’s name and the MAS finally became a full-fledged central bank with the ability to issue banknotes and coins.17

The merger took place without much fanfare. Recalled J.Y. Pillay, former deputy chairman and managing director of MAS: “I was in the UK at that time… it may well be that somebody, if not an MP, an NMP or someone would say: ‘What’s happening? Are we going to loosen our monetary policy? Is this a sign of incipient price instability?’ But at that time, not a squeak from anywhere and not even remarked upon in the international media.”18

Overcoming Crises and Challenges

With or without the ability to issue currency, the MAS has played a vital role in Singapore’s economic development over the last 50 years.

The MAS has kept inflation low, maintained healthy official foreign reserves, established a sound financial sector which is resilient against shocks, and built up a vibrant international financial centre that adds value and creates jobs.19

Over the last five decades, the MAS has weathered numerous storms. Many of these were external, such as the collapse of the Bretton Woods Agreement that led to the end of the system of fixed exchange rates, as well as the oil shocks of the 1970s. As Singapore is a small open economy, the MAS has had to deal with the consequences of these and many other global events. However, there were also some specific to Singapore or Southeast Asia that required the MAS to respond. One of the most severe was the Pan-El crisis of 1985.

Pan-Electric Industries Crisis

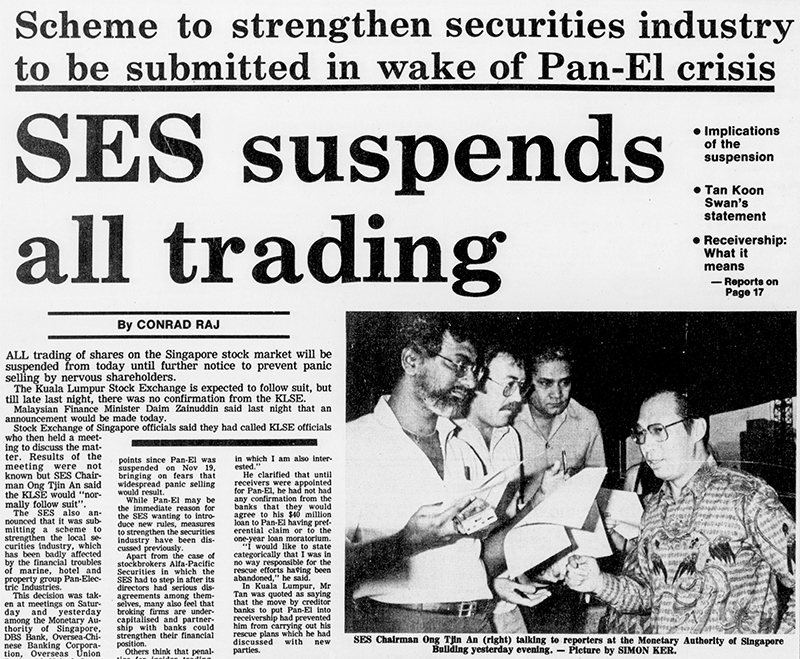

On 30 November 1985, Pan-Electric Industries Limited, a company listed on the Stock Exchange of Singapore, collapsed and was placed under receivership. A marine salvage, hotel and property group, it had amassed huge debts of $453 million owed to 35 banks and $160 million worth of unfulfilled forward contracts.20

In an unprecedented move, the stock exchange was closed for trading from 2 to 4 December 1985 in a bid to stabilise the market and mitigate against any contagion effect and fallout on the heavily leveraged stockbroking firms. The closure was considered a drastic move and in doing so, “Singapore had to pay the price in terms of economic, reputational and social costs”.21

The MAS stepped in with a bail-out plan by setting up an emergency “lifeboat” fund consisting of a $180-million line of credit underwritten by the “Big Four” local banks, accompanied by a three-month moratorium on the recall of loans to stockbrokers. The fund was designed to prevent the wholesale and systemic collapse of the stockbroking industry, and to restore public confidence.22

The system of forward contracts, in which shares are resold before their purchases have been settled, was the crux of the Pan-El crisis. With forward trading, a whole chain of parties was linked via promises of sale and purchase to the same lot of stock. A domino effect was created by defaults down the chain. Given the massive number of forward contracts it had entered into, Pan-El was unable to fulfill them and was plunged into insolvency.23

Following the incident, the MAS “restricted the trading of forward contracts and toughened insider trading rules”. They also introduced measures to ensure that Singaporeans remained cautious and prudent with their money and investments.24

Collapse of Barings

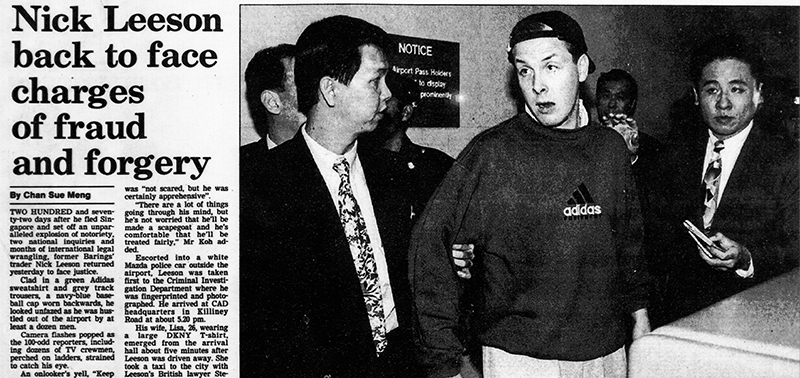

A decade later, MAS had to deal with the collapse of Barings Bank, Britain’s oldest merchant bank, triggered by events in Singapore. Nicholas William Leeson, better known as Nick Leeson, was a derivatives trader and the general manager of Barings Futures Singapore. His excessive trading in Nikkei index futures chalked up great losses and saddled the bank with a huge debt. By the time of the bank’s collapse on 26 February 1995, it had accumulated losses amounting to $2.2 billion.25

The MAS was alerted and immediately swung into action by clearing the trades and closing up positions to safeguard the reputation of the Singapore International Monetary Exchange (SIMEX) and to restore public confidence in Singapore’s standing in the market. This became an internationally high-profile case that dominated headlines around the world. Fortunately, the losses incurred by Barings Futures Singapore and the consequent collapse of its parent bank in London did not have an adverse effect on the reputation of Singapore’s financial sector.26

Explained Richard Hu, then chairman of the MAS: “When Barings happened, of course, Koh Beng Seng [then deputy managing director] and his team were very quick to act. They went immediately to Barings, took the books and discovered how the sequence of events took place. And it was very clear. Leeson was mainly speculating in Nikkei-225 futures and reporting profits which did not exist. As far as the home office was concerned, this unit in Singapore was making money and they provided more funding to increase the size of its business.”27

The incident led to the amendment of the Futures Trading Act, which came into force on 1 April 1995, and enabled the MAS to monitor the trading of futures contracts more closely. Measures were also introduced to strengthen the regulatory framework of futures trading under SIMEX.28

Asian Financial Crisis

Soon after the collapse of Barings, the MAS had to deal with the Asian Financial Crisis, which erupted following the collapse of the Thai baht on 2 July 1997 when it depreciated by 15 percent. The contagion spread rapidly to other Southeast Asian currency markets, including Singapore, and caused the Singapore dollar to weaken against the US Dollar.

Central banks in the region raised interest rates and imposed capital controls but failed to restore stability in the currency markets. Various Southeast Asian countries sought help from International Monetary Fund programmes to help their economies tide over the crisis. In mid-January 1998, the Malaysian ringgit, Thai baht and Philippine peso fell to historic lows against the US dollar.29

What started as a currency crisis had impacted the wider economy and the rest of the region. Although Singapore was not directly hit, the country suffered the spill-over effects of the economic slowdown and entered a recession in the second half of 1998.30 GDP growth plunged from 8.4 percent in 1997 to 0.4 percent in 1998. But the banks stood firm and Singapore companies did not go under.

Singapore’s strong economic fundamentals, including MAS’s healthy buffer of official foreign reserves and its prudent management and monitoring of the exchange rate, helped to ensure that the Singapore dollar maintained its value. It capped the degree to which the Singapore dollar weakened against the major reserve currencies of the US, Europe and United Kingdom, and protected the Singapore dollar from depreciating to the same extent as other regional currencies.

Cost-cutting measures were also implemented to support the economy. In November 1998, the government introduced a $10.5-billion cost-reduction package that included a 10-percentage point reduction in employers’ Central Provident Fund contributions, a wage cut of 5 to 8 percent, and further cuts in government rates and fees.31

By early 1999, the Singapore economy had begun to show signs of recovery and returned to positive growth in the first quarter of that year. Singapore’s low foreign debt, huge foreign exchange reserves, large budget surpluses, high savings rates, low inflation and a sound financial system had helped it to overcome the crisis.32

Global Financial Crisis

Some 10 years later, the MAS had to deal with an even larger crisis when the world was plunged into the worst economic crisis since the Great Depression of the 1930s.33 The slowdown and contraction of developed economies were particularly sharp in the last quarter of 2008 following the collapse of America investment bank Lehman Brothers in September, and the near-collapse of American International Group, the world’s largest insurer. By the end of 2008, the major economies had slipped into deep recession and this exacted a heavy toll on Asia’s trade-reliant economies.

Singapore was not immune and slipped into a recession as well. In response to these events, the MAS immediately acted to ensure the stability of the Singapore dollar and the banking system. To ease pressures on the Singapore dollar market activity, MAS kept a higher level of liquidity in the banking system. It also reassured financial institutions that it would continue to anticipate the market’s funding needs and consider any unique liquidity needs of individual banks on a case-by-case basis.34

In fact, as early as the start of 2007, when signs of the impending crisis first began brewing, the MAS had already stepped up their supervision of foreign banks in Singapore. MAS drew up contingency plans to safeguard the interests of depositors and investors in case any foreign bank in Singapore failed because of problems back home. It also announced a guarantee for all Singapore dollar and foreign currency deposits in banks, finance companies and merchant banks licensed in Singapore.35

Due to MAS’s quick thinking and sound policies, Singapore’s financial sector was not greatly impacted and in August 2009, Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong announced that “the worst is over for the Singapore economy” and that “the eye of the storm has passed”.36

The Next 50 Years

In October 2021, Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong noted that the monetary policies and management of official reserves by MAS had “sustained macroeconomic stability and confidence in Singapore. Its regulation and supervision of financial institutions [had] created a safe and internationally trusted financial system”.37

He attributed these achievements to caution and creativity on the part of the MAS. “It adhered to sound economic principles, while creatively adapting policy frameworks to suit Singapore’s context,” he said. “It set high regulatory and supervisory standards, while taking a facilitative and risk-proportionate approach. It ensured financial stability, while promoting innovation and seizing opportunities.”38

Today, the world is being roiled by events such as the Covid-19 pandemic and the war in Ukraine. Inflationary pressures threaten global economies while the consequences of climate change loom increasingly large on the horizon. Now, more than ever before, the MAS will need to bank on its guiding principles of caution and creativity to help Singapore navigate safely through an uncertain and unpredictable future.

Barbara Quek is a Senior Librarian with the National Library, Singapore. She is part of the team that oversees the statutory functions at the National Library Board in the compliance of Legal Deposit in Singapore. Her work involves developing the National Library’s collections through gifts and exchange as well as providing content and reference services.

Barbara Quek is a Senior Librarian with the National Library, Singapore. She is part of the team that oversees the statutory functions at the National Library Board in the compliance of Legal Deposit in Singapore. Her work involves developing the National Library’s collections through gifts and exchange as well as providing content and reference services.NOTES

-

“No Longer De facto Central Bank,” Straits Times, 25 August 1998, 44. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Hon Sui Sen, “Establishing the Monetary Authority of Singapore,” in Resilience, Dynamism, Trust: 50 Landmark Statements by MAS Leaders (Singapore: World Scientific, Monetary Authority of Singapore, 2022), 4. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 332.11095957 RES) ↩

-

Hon, “Establishing the Monetary Authority of Singapore,” in Resilience, Dynamism, Trust, 4. ↩

-

Goh Keng Swee, “Speech by Dr Goh Keng Swee, Minister for Finance, at the 13th Anniversary Dinner of the Economic Society of Singapore,” Dragon Room, Robinson Restaurant, 20 September 1969, transcript, Ministry of Culture. (From National Archives of Singapore, document no. PressR19690920d) ↩

-

Ignatius Low, Fiona Chan and Gabriel Chan, Sustaining Stability: Serving Singapore (Singapore: Straits Times Press, 2012), 67. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 332.11095957 LOW) ↩

-

Hon, “Establishing the Monetary Authority of Singapore,” in Resilience, Dynamism, Trust, 5. ↩

-

Low, Chan and Chan, Sustaining Stability, 67. ↩

-

Low, Chan and Chan, Sustaining Stability, 67. ↩

-

Low, Chan and Chan, Sustaining Stability, 66. ↩

-

Clement Liew and Peter Wilson, A History of Money in Singapore (Singapore: Talisman Publishing, 2021), 351. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 332.4095957 LIE) ↩

-

Paul Wee, “Central Bank ‘in July or August’,” Straits Times, 23 May 1979, 1; Soh Tiang Keng, “Central Bank Plan Put Off: A New Appraisal?,” Straits Times, 25 October 1980, 1. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Liew and Wilson, A History of Money in Singapore, 351. ↩

-

Lim Hng Kiang, “MAS Merges with Board of Commissioners of Currency,” in Resilience, Dynamism, Trust, 114. ↩

-

Lim, “MAS Merges with Board of Commissioners of Currency,” in Resilience, Dynamism, Trust, 114–15. ↩

-

Lim, “MAS Merges with Board of Commissioners of Currency,” in Resilience, Dynamism, Trust, 115. ↩

-

Liew and Wilson, A History of Money in Singapore, 352–53. ↩

-

Low, Chan and Chan, Sustaining Stability, 70–71; “BCCS Merges with MAS on 1 October,” Monetary Authority of Singapore, 20 September 2002, https://www.mas.gov.sg/news/media-releases/2002/bccs-merges-with-mas-on-1-october–30-september-2002; “Our History,” Monetary Authority of Singapore, last updated 21 April 2022, https://www.mas.gov.sg/who-we-are/Our-History. ↩

-

Low, Chan and Chan, Sustaining Stability, 71. ↩

-

Lee Hsien Loong, “PM Lee Hsien Loong’s Speech at the MAS50 Partners Appreciation Evening on Thursday, 7 October 2021,” Prime Minister’s Office Singapore, last updated 8 October 2021, https://www.pmo.gov.sg/Newsroom/PM-Lee-Hsien-Loong-at-the-MAS50-Partners-Appreciation-Evening. ↩

-

Mimi Ho, et al., “Case Study on Pan-Electric Crisis,” MAS Staff Paper, no. 32 (July 2004): 11, 15, https://www.mas.gov.sg/publications/staff-papers/2004/mas-staff-paper-no32-jul-2004; “The Pan-Electric Crisis,” Straits Times, 3 December 1985, 23; Lynette Khoo, “1984: Taking Jardine Fleming to Task,” Business Times, 29 February 2016, 4. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Ho, et al., “Case Study on Pan-Electric Crisis”, 66. ↩

-

Ho, et al., “Case Study on Pan-Electric Crisis,” iii–iv. ↩

-

A forward contract is a stock acquisition contract established between two parties for delivery at a predetermined time in the future, at a price agreed upon in the present. It is used for hedging, enabling share owners to reduce price risk by selling their shares forward. This, however, induces share roll-over among multiple parties, including investors, brokers and corporations, as in the Pan-El situation. See Ho, et al., “Case Study on Pan-Electric Crisis,” 9–10. ↩

-

Low, Chan and Chan, Sustaining Stability, 116–17. ↩

-

Louis Beckering, “The Fall of the House of Barings,” Straits Times, 30 July 1995, 4; Chan Sue Meng, “Leeson Saga, and Key Role of 88888 Account,” Straits Times, 24 November 1995, 49; “The Fateful, Frantic Hours That Broke a Bank,” Business Times, 4 March 1995, 3. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Low, Chan and Chan, Sustaining Stability, 165, 186. ↩

-

Low, Chan and Chan, Sustaining Stability, 184. ↩

-

Quak Hiang Whai, “Govt to Tighten Supervision of Futures Trading,” Business Times, 2 March 1995, 4; Paul Leo and Siow Li Sen, “Law Tightened to Prevent Another Barings,” Business Times, 21 March 1996, 1; Chan Wee Chuan, “Investors Better Protected with Changes to Futures Trading Rules,” Straits Times, 8 April 1996, 36. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Monetary Authority of Singapore, Annual Report (Singapore: The Authority, 1997/1998), 34–35. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RCLOS 32.495957 MASAR-[AR]) ↩

-

“Asian Financial Crisis (1997–1998),” in Singapore Infopedia. National Library Board Singapore. Article published 30 July 2016. ↩

-

Low, Chan and Chan, Sustaining Stability, 189. ↩

-

Low, Chan and Chan, Sustaining Stability, 187; Walter Fernandez, “Recession Over But It’s Not Time to Rejoice,” Straits Times, 20 May 1999, 1. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Low, Chan and Chan, Sustaining Stability, 190. ↩

-

“Spore’s Economy in Recession,” Today (2nd Edition), 10 October 2008, 1. (From NewspaperSG); Low, Chan and Chan, Sustaining Stability, 192–93. ↩

-

Low, Chan and Chan, Sustaining Stability, 193. ↩

-

Alvin Foo, “Worst Is Over for Singapore’s Economy,” Straits Times, 17 August 2009, 4. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Lee, “PM Lee Hsien Loong’s Speech at the MAS50 Partners Appreciation Evening on Thursday, 7 October 2021.” ↩

-

Lee, “PM Lee Hsien Loong’s Speech at the MAS50 Partners Appreciation Evening on Thursday, 7 October 2021.” ↩