Theemithi: A Look at the Full Cycle of Rituals Behind the Festival of Firewalking

Theemithi is much more than just the firewalking festival. It is a cycle of rituals that involves the re-enactment of events from the Mahabharatam over several months.

By Nalina Gopal

In October 1893, the manager of the Sri Mariamman Temple on South Bridge Road hired a lawyer to represent the temple in the Senior Magistrate’s court in Singapore.1 The man he chose was Walter John Napier, the co-founder of Drew & Napier, later the Attorney-General of the Straits Settlements. The suit? Police Superintendent Bell had filed an injunction against the temple to prevent the firewalking festival from taking place that year.

In Napier’s winning defence of the right of “[Hindoos to]… practice their particular rites and ceremonies without any interference from the Government”, he refers to the festival being celebrated in Singapore since 1835.2 This reference puts the age of the annual festival of Theemithi to within 20 years of the establishment of a British outpost in the littoral city.

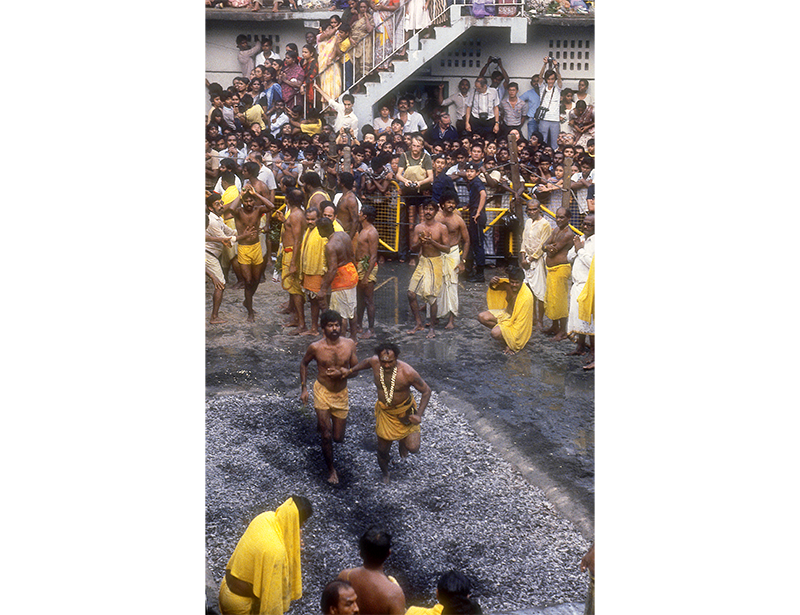

Theemithi, which means “firewalking”, is observed during the Tamil month of Aipassi (mid-October to mid-November) at the Sri Mariamman Temple. Over the past decades, firewalking has taken place a week before Deepavali (on a Sunday), witnessed by thousands, including devotees and the curious.

This spectacular event has, however, eclipsed the associated cycle of rituals that take place over a three-month period before the festival. These rituals are an elaborate retelling of events from the Mahabharatam, speaking of an epic devotion kept alive in the diaspora for close to two centuries.3

Antecedents: The Mahabharatam

To understand the events that collectively constitute the festival of Theemithi, one must turn to the Indian epic poem, the Mahabharatam (known as the Mahabharata in Sanskrit and Mahabharatam in Tamil.)

Inscriptional evidence points to the prevalence of the reading of the poem as early as the 7th century CE.4 The reading of the epic is a tradition that continues to the present, particularly during the festival of Theemithi.

The goddess Draupadi (also spelled Drowpathai), whose worship is associated with Theemithi, is the deified heroine of the Mahabharatam. Draupadi is the wife of the five Pandava brothers. Wronged by the Kauravas, the scheming cousins of the brothers, she vows vengeance. An 18-day battle – known as the Kurukshetra War – ensues, resulting in the victory of the Pandavas and the appeasement of Draupadi.5

This story, contained in 18 parvam or books in Tamil and other versions, unfolds through an elaborate re-enactment or ritual drama during the festival of Theemithi, from the engagement ceremony and loss to victory and coronation. (The oldest surviving copies of the Mahabharatam used at the Sri Mariamman Temple in Singapore, likely read during the proceedings of the festival, go back to the last decade of the 19th century. These are now in the collection of the National Archives of Singapore.6)

Sri Periyachi Amman Poojai

The approximately three-month-long cycle of rituals commences with an invocation to the mother goddess, Periyachi Amman, in the Tamil month of Aadi (mid-July to mid-August) at the Sri Mariamman Temple. This tradition, too, has precedent in the epics – an autumn prayer to the goddess Durga was performed by Rama to defeat the demon king Ravana in the Ramayana, and by the Pandavas to defeat the Kauravas in the Mahabharatam.

On the day of the prayer dedicated to Periyachi, which takes place on a Sunday in the month of Aadi, Mariamman is manifested in the karagam, or water vessel, embellished with margosa leaves (also known as neem leaves, and generally associated with the worship of Mariamman), flowers and lemons.7

The pandaram, or priest, carries the mother goddess in the form of the karagam on his head and a margosa stem in hand. He dances around the temple grounds, stopping from sanctum to sanctum. Once done, the priest changes his garb and adorns the attire of Madurai Veeran, the guardian of the goddess.

In a trance, with coconut flowers in one hand and a staff in the other, the pandaram dances before Periyachi Amman at her shrine. He is then handed a giant cauldron of fire, or agni kapparai, which he carries around the temple. At this point, the agni kapparai represents the mother goddess herself. The goddess is thus manifested through the mediums of water, fire and even the priest.8

Sri Draupadi Amman Kodiyetram

Following the invocation of the mother goddess, a large flag is hoisted at the kodimaram, or flag post, in front of the shrine of Draupadi the following day. The kodiyetram, or hoisting of the flag, symbolises the commencement of the Theemithi cycle.

The reading of the Mahabharatam begins on the day the flag is hoisted, and a portion of the epic is read nightly thereafter. In the 1960s and 1970s, the reading was done by a volunteer known to all as Bharata poosari. According to E.V. Singhan’s account of the festival in 1976, the reader was paid more than $160 for his efforts.9 In the 1990s, the writer and radio producer M.K. Narayanan would read the epic to an audience of devotees at the Sri Mariamman Temple.10 Today, it is read by the chief priest.

The preparation of the kodi, or flag, is itself an elaborate process. A new kodi has to be made annually. The white, cotton fabric – about 45 m long and a metre across – is sourced from a textile store at Jalan Sultan by volunteers, according to a 2022 interview with Moti Lal Prasad. (Lal Prasad has been a volunteer at the temple since 1982 when he joined the Navaratri boys group.11)

According to Prasad, “the kodi is then taken to a tailor in Little India to be finished, and from there, to the temple to be framed and made ready for painting. An artist known as Mr Sam then paints the image of Hanuman or Anjaneyar” (the monkey god) carrying the Sanjeevani Hill in his right hand. Hanuman’s inclusion is reminiscent of Draupadi and Bhiman’s (one of the Pandava brothers) encounter with the deity in the Mahabharatam.

The painting of Hanuman spans only about 1.2 m by 1 m of the enormous flag. After it is painted, it is removed from the frame. On the day of the flag hoisting, the kodi is decorated with silk and flowers. Following rituals, the flag is then hoisted and remains on the flag post till the end of Theemithi. The taking down of the flag marks the end of the festival. The flag is then cut and the painted portion kept in storage, while the unpainted portion is discarded.12

In the Mahabharatam, Draupadi is “won” by the Pandava prince Arjunan at a swayamvaram (competition for prospective grooms). He brings her home to his mother Kunti, who orders him to share his winnings with his four brothers. Thus, she comes to be married to all the five Pandava brothers.

In the Tamil renditions of the epic – and indeed in the Draupadi cult as well as during Theemithi – Draupadi, Arjunan and the god Krishnan are situated as the divine triumvirate with unparalleled powers. (In other versions of the Mahabharatam, this trio is not considered the central triad.)

Sri Draupadi Ammanukku Malaiyithudal

During Theemithi, a unique retelling of the epic unfolds that places Draupadi as the central character. It commences with Draupadi’s engagement ceremony. Called Malaiyithudal, the ritual marks the betrothal of Arjunan and Draupadi and is held on the Monday just after the flag is hoisted. The processional images of the two are dressed, adorned with fresh flower garlands, and decorated. Ubhayakarar (patrons) represent the groom’s and bride’s families during the rites.

![]()

After the rites are performed by priests, the polychrome figures are carried by volunteers in circumambulation within the temple, together with the processional images of Krishnan and Virabadran, the latter being a munnodi deivam or frontrunning guardian of Draupadi.

Sri Draupadi Ammanukku Thirukalyanam

On the Monday after Malaiyithudal a week later, Thirukalyanam, or the wedding of Draupadi, is held.

The Thirukalyanam comprises a series of ostentatious marriage rites that include a ceremonial dance by two garland-bearing priests, who go on to exchange the garlands before draping the garlands on the processional icons of Arjunan and Draupadi. Following this, a thali (wedding pendant) is tied around Draupadi’s neck to symbolise her married status.

Sri Draupadi Vasthiraparanam

The ritual that takes place a week after Thirukalyanam is perhaps the one that involves the fewest number of people. Priests, temple staff, volunteers and a small number of devotees witness the unbearable humiliation of Draupadi: Draupadi Vasthiraparanam. This is the disrobing of Draupadi in an open court after the eldest Pandava brother, Dharmaraja, loses to the Kauravas in a game of dice. However, Krishnan comes to her rescue and prevents her humiliation.

The episode is relived ceremonially; the pandaram covers the red sari worn by Draupadi’s processional image with a yellow one and unties her bound hair.13 These actions signify her vow to seek vengeance against those who have wronged her.

Arjunan Thabasu

From this point onwards, elements of ritual theatre come to the fore. These are rooted in the Bharata koothu tradition of ritual performances held in Draupadi temples in the northern districts of Tamil Nadu during the lead-up to the firewalking festival.14 A volunteer takes on the role of the hero Arjunan, portraying his ascetic efforts to receive a weapon called pasupastra from the deity Siva. Undisturbed by the many distractions sent his way by his devious cousin Duryodhanan, Arjunan achieves his goal.

Called Arjunan Thabasu, this event takes place on a Friday, a few weeks after Draupadi Vasthiraparanam. It involves Arjunan climbing the thabasu maram, which represents a bael tree in the Himalayas, where he meditates to receive the weapon. The thabasu maram is installed in the morning, and in the same evening the re-enactment takes place.

The thabasu maram – the most elaborate of ritual props used in the cycle of events – is a seven-metre-high pole painted dark brown like a tree trunk with 11 steps and a platform at the top. The platform is decorated either with flowers, or at times with cotton applique cloth, and four thombai (hanging decoration).

The volunteer in the role of Arjunan ascends the pole after reciting an invocation in Tamil. The proceedings conclude with a circumambulatory procession around the temple grounds, which ends at the shrine of Draupadi.

In the 1970s, the re-enactment of Arjunan Thabasu took place after the sacrifice of Aravan, during the battle of Kurukshetra between the Pandavas and the Kauravas, a central element in the Mahabharatam.15 It is not known when this ritual was moved to earlier in the cycle, to reflect Arjunan’s penance occuring before the battle.

Keesaga Samharam

At this point, the episode from the Virata Parvam (the fourth book of the Mahabharatam that sees the Pandavas living incognito in exile) is read and included in the cycle. In the episode, the Pandava brother Bhiman vanquishes the army commander Keesaga of the kingdom of Virata for making advances on Draupadi.

Aravan Poojai and Aravan Kalapali

A distinctive mythology of Aravan (also known as Nalaravan and Koothandavar), the son of Arjunan and the Naga maiden Ulupi, was established in the 9th century CE Bharatam.16 Aravan is not only a central figure in the Theemithi cycle of events, he also commands a cult of his own. Aravan has a temple dedicated to him at Koovagam village in the Kallakurichi district of Tamil Nadu. In Singapore, the Sri Mariamman Temple has a permanent shrine dedicated to him, which is located southeast of the Draupadi shrine.

In the epic, Aravan is sacrificed to Kali to attain victory for the Pandava brothers. In the Theemithi cycle, this sacrifice is symbolically performed by the pandaram. Aravan Kalapali (battlefield sacrifice) takes place on amavasai, or “new moon day”, in the Tamil month of Purattasi (mid-September to mid-October), at least 18 days before the firewalking.17

For this, small heaps of rice mixed with kungumam (vermillion) are placed on a white cloth adorning the neck of Aravan’s processional image, together with quarters of poosani (white pumpkin) smeared with vermillion, representing the blood of Aravan. The 32 heaps of rice symbolise the self-mutilated pieces of Aravan’s flesh and hallmarks of perfection, or purusha lakshanam, which Aravan is said to have sacrificed to Kali.

Before he is sacrificed, Aravan asked Krishnan for three boons – to get married, to die heroically on the battlefield, and to witness the entire war and its outcome. He is granted the first when Krishnan takes his female form as the enchantress Mohini and marries him. Aravan’s severed head – present in processional and immoveable forms at the temple – witnesses the events of the war leading up to Theemithi.

Aravan Poojai (ritual prayer) is offered to Aravan before his shrine and takes place on the Monday before Aravan Kalapali. Muthala Raja (better known in Tamil Nadu as Muthala Ravuttan, the Muslim shrine guardian), the guardian of Draupadi, is also revered at his shrine located northeast of Draupadi’s. The processional image of Aravan is then carried around the temple by volunteers, almost like a final celebration of his life before his self-sacrifice.

On the day of Aravan Kalapali, a pair of temple volunteers assume the roles of Draupadi and Krishnan. They re-enact the scene of Krishnan convincing Draupadi that the sacrifice of Aravan is essential to guarantee the victory of the Pandava brothers. Draupadi then carries a soolam, or trident, decorated with a yellow cloth, around the temple, and plants it like a battle flag in the ground near Aravan’s shrine, marking the start of the Kurukshetra battle.

Sambasivam Paikirisamy, a volunteer, recalled that in the 1960s, Aravan Poojai used to be less elaborate and involved fewer people. The group of volunteers who handled matters relating to Aravan registered a visesha poojai (special prayer) from 1975 to make it officially part of the cycle of events. The volunteers aided the conduct of Aravan Poojai and Kalapali rites, including anna danam (distribution of free food). He also recalled that in the 1960s and 1970s, Aravan’s form was seen as fiercer than it is today, and women were asked to keep a distance during Kalapali.18

Balakrishnan Veerasamy Ramasamy, a volunteer who assumed the vesham (role) of Draupadi for about 20 years from the early 1980s, recalled being cautioned by his mother that the role play was not a game. She also warned him that he might be teased by his friends for dressing like a woman. Balakrishnan, however, felt that it was a rare opportunity and blessing to serve Draupadi. He was 25 when he was asked to do so by the temple’s chairman, P.G.P. Ramachandran. Balakrishnan recalled the shock he felt when he first took on the role of Draupadi during Aravan Kalapali and experienced going into a trance.19

Chakravarti Kottai

Chakravarti Kottai, or the wheel fort incident, occurs the day before the actual firewalking. This ritual pertains to the entrapment of Abhimanyu (one of the sons of Arjunan) on the battlefield. Unable to escape the wheel-like concentric formation of soldiers, Abhimanyu dies during the war. The Chakravarti Kottai is installed in the form of a multi-coloured, three-dimensional mandala and fortress-like structures constructed with sand, flowers and rangoli powder.

Positioned in front of Aravan’s shrine, volunteers take the lead in this ritual.20 Four sword-bearing volunteers go down on one knee, each on one side of the square mandala, while the fifth sword-bearer positions himself adjacent to the mandala. Then three whip-wielding volunteers stand in a straight line in front of the mandala and swirl the whips in the air in a circular motion.

A volunteer representing Abhimanyu lies down on a thin, white fabric and is completely wrapped in the cloth by other volunteers on standby. As this is done, the volunteers positioned around the mandala run across the carefully constructed wheel fort, thus obliterating it, and the entire group moves to the sanctum of Draupadi. It is believed that the volunteer who is wrapped in the white cloth loses consciousness during the transit to Draupadi’s shrine and is revived when he is placed before Draupadi.

Padukalam

Padukalam marks the last day of the Kurukshetra battle and takes place on the morning of the firewalking event. It brings to an end the cycle of epic-based re-enactments explaining the root legends for the cult of goddess Draupadi. Padukalam, which means “dying/lying down on the battlefield”, is an elaborate re-creation of battlefield rituals that focuses on Draupadi, who has to decide if the Pandava and Kaurava casualties of war should receive salvation or damnation.

Volunteers construct five effigies made of sand mounds around the battlefield representing five fallen warriors. Volunteers playing the roles of Draupadi and Krishnan go to each of the effigies. Draupadi asks that the souls of the first three – that of Abhimanyu, Drona and Karnan – be allowed to go to heaven. She sprinkles turmeric on them and gently expunges their faces with her hand.

The fourth effigy represents Dushasanan, the one responsible for her dishonour. For this, Draupadi consigns him to hell. She kicks his effigy, breaking it down. At the last effigy, Draupadi discovers that it is Duryodanan, the one who shamed her, and she is incensed. Volunteers quickly lay a white cloth on the effigy; a volunteer lies on it and is wrapped in the cloth and carried away to the shrine of Draupadi where Duryodanan is consigned to the netherworld.

Her vow of vengeance achieved, Draupadi combs her hair and ties it. Volunteers quickly assist the priests to do the same for the processional image of Draupadi. Her yellow sari is changed to red, and her hair knotted into a bun.21 It is only after these rituals are completed that the preparations for the firewalking can begin.

How does all this relate to firewalking? Born of the fire during a yagnam or fire ritual,22 Draupadi is believed to protect whoever takes the vow to walk through the fire by making the coals as cool as flowers.

In the various Tamil versions of the epic, four different pre- and post-battle origin myths involve Draupadi walking on fire. These include her proving her chastity after marrying the five Pandava brothers, after her encounter with Keesaga (who makes advances on her), and a post-battle purification. The fourth is one that suggests the ritual’s association with the revival of Draupadi’s sons who are sacrificed during the war.23

Walking on Coals

Throughout the day, volunteers at the Sri Mariamman Temple help to build the firepit. Over the years, the width of the pit has changed to take into consideration safety measures.24 Currently, the pit is around 18 feet (5.5 m) in length, in reference to the 18 days of the Kurukshetra battle. In the morning, the chief pandaram conducts a ritual during which margosa leaves and burning firewood chunks brought from the shrine of Draupadi are used to light up the pit.

At about 6 pm, the karagam would be constructed at the Sri Srinivasa Perumal Temple on Serangoon Road, and at around 7 pm, the five-kilometre-long foot procession to Sri Mariamman Temple commences. The procession is led by the chief pandaram carrying the karagam on his head, followed by the 2,000 or so devotees. As the group approaches Sri Mariamman Temple, a temple official sprinkles jasmine flowers in the fire pit and throws lemons on the embers.

The firewalking starts at around 8.30 pm with the chief pandaram being the first to walk across the fire pit. Thereafter, the five sword-bearers of Draupadi will be among the first devotees to walk the fire. Wearing jasmine garlands and carrying margosa leaves, devotees typically run across the pit. When they reach the other end, the devotees would dip their feet in a milk pit before proceeding to the shrine of Draupadi to offer the margosa leaves. Once the last devotee has crossed the pit, the flames are put out with milk from the same milk pit and with running water. The whole event ends at around 2.30 am.

Two days after the firewalking, the festival finally concludes with the coronation of Dharmaraja, the eldest of the Pandava brothers, and the Manjal Neerattu, a celebration of victory involving the splashing of turmeric water. Thereafter, the kodi is taken down, and all ritual objects and the Mahabharatam stored away.

Theemithi and the Sri Mariamman Temple

The cult of Draupadi and her shrine at the Sri Mariamman Temple are attributed to a community of caulkers, or boat workers, who came from the village of Vadakku Poigainallur in Nagapattinam district.25

The temple’s association with littoral communities goes back to its very foundation. Naraina Pillai was a native of the Coromandel Coast, and he is described as such in a letter written by Resident of Singapore William Farquhar in December 1822.26 Pillai was the driving force behind the establishment of the Sri Mariamman Temple – not only providing the funds for the purchase of the temple site but also installing the main deity when the temporary structure was completed in 1827.27

Some overlaps in the cults of Mariamman and Draupadi are evident in the festival. For instance, in the 1960s and 1970s,28 devotees would fulfil their vows to Mariamman by carrying kavadi, reminiscent of a Mariamman thiruvizha festival, like the one still held in Melaka known as Sembahyang Dato Charchar. Today, devotees in Singapore no longer carry kavadi during Theemithi.

During firewalking, it is also the vepailai karagam (the consecrated vessel) associated with Mariamman that is carried by the chief pandaram across the firepit. The Sri Mariamman Temple is a syncretic space accommodating shrines of other gods and goddesses, including Draupadi.29 The highest respect, however, is always accorded to Mariamman.

As the accounts above show, Theemithi celebrations have changed over the years in Singapore. In fact, while the festival is closely associated with the Sri Mariamman Temple now, during parts of the 19th century, the firewalking used to take place on Albert Street earning the street the Tamil name Theemithi Thidal (“open field”).30 The engagement of John Napier by the temple in 1893 shows that the practice had long migrated to the temple by the late 19th century.

And while the firewalking today is a male activity, in the 19th century, women too walked over the coals and did so up to the early 20th century. In fact, Police Superintendent Bell’s case was lodged in 1893 after hearing about a female devotee who had fallen into the firepit. We do not know when or why women stopped walking across the pit, but today, someways women participate in the ceremony include lighting the maavilakku (a lamp made of rice flour), performing kumbuduthandam31 (“repeated kneeling down and touching the floor with the head around the temple”), or carrying out angapradakshinam (“rolling on the ground”).

Of course, the rituals have changed as well over time. Some have become more elaborate, such as the Aravan Poojai, while others are no longer carried out, such as the ritual slaying of goats and the whipping of devotees.

The space accorded for change has kept Theemithi a living one. Moreover, the festival has forged together an ever-renewing, inter-generational community of volunteers, families and practitioners who keep strong the tradition of this epic devotion.

Theemithi is both public yet widely misconstrued. While the act of walking on fire itself has consumed the attention of observers for close to two centuries, the participants’ account of the almost three-month-long festival clearly belies that singular focus on the spectacular.

It is a festival rendered invisible not by the lack of, but by the excess of light or exposure. It is like that old and overexposed photograph in a photo album that has only one detail in focus, the rest washed out because the aperture setting and shutter speed were out of sync. The oldest paradox of prejudice is that it renders its subject at once invisible and overexposed.32

Nalina Gopal is an independent curator and researcher focused on South Asia and its diaspora. She is the founder of Antāti, a historical research and museum consultancy.

Nalina Gopal is an independent curator and researcher focused on South Asia and its diaspora. She is the founder of Antāti, a historical research and museum consultancy.NOTES

-

“The Hindoo Religious Ceremony,” Straits Times Weekly Issue, 24 October 1893, 6. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

The Mahabharata, one of the two great Indian epics originally written in Sanskrit (the other being the Ramayana), is thought to have been composed between 400 BCE and 400 CE, and to a shorter period by Alf Hiltebeitel dating from the mid-2nd century BCE to the start of the Common Era. ↩

-

Alf Hiltebeitel, The Cult of Draupadi, Volume 1: Mythologies: From Gingee to Kurukshetra (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1988), 14. ↩

-

In the Mahabharata, the core narrative revolves around warring cousins, the Kauravas (the sons of King Dhritarashtra and the heirs of the lineage of the clan’s ancestor and great king Kuru) and the Pandavas (the five sons of king Pandu). Their antagonistic relationship results in the battle of Kurukshetra, an epic battle that is thought to have taken place around 1200 BCE on the basis of archaeological evidence discovered in the modern Indian state of Uttar Pradesh. More recent excavations have raised questions of the possibility of an earlier dating for the epic-related events. ↩

-

Cinkappur Sri Mariyamman Kovil, Mahaparatham, private records, 1896 (From National Archives of Singapore, microfilm no. NA1984); Cinkappur Sri Mariyamman Kovil, Hindu Religious Book Vol.1 Mahaparatham, private records, 1897. (From National Archives of Singapore, microfilm no. NA1982) ↩

-

The water vessel is filled with approximately 5 kg of rice, a gold coin and one lemon. A stick is anchored in the rice and margosa leaves attached to the vessel. Once secured, malli and mullai (both are different varieties of jasmine) flowers are wrapped around the structure. The mukham or silver image of the face of the mother goddess, Periyachi Amman, is attached to the front demonstrating that the karagam personifies the goddess. ↩

-

Indira Arumugam, “Migrant Deities: Dislocations, Divine Agency, and Mediated Manifestations,” American Behavioral Scientist 64, no. 10 (2020): 1463, https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764220947763. ↩

-

E.V. Singhan, Timiti Festival (Singapore: EVS Enterprises, 1976), 8. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 294.538 SIN) ↩

-

Balakrishnan Veerasamy Ramasamy, interview by author, 13 July 2022. ↩

-

Moti Lal Prasad, interview by Tharmalingam Kavindran and author, 5 June 2022. ↩

-

Prasad, interview. ↩

-

Lawrence A. Babb, “Walking on Flowers in Singapore: A Hindu Festival,” Eckistics 39, no. 234 (May 1975): 333. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website) ↩

-

M.D. Muthukumarasamy, “Trance in Fire Walking Rituals of Goddess Tiraupati Amman: Temples in Tamilnadu” in Emotions in Rituals and Performances: South Asian and European Perspectives on Rituals and Performativity, ed. Axel Michaels and Christoph Wulf (New Delhi: Taylor & Francis, 2012), 140–42. ↩

-

Singhan, Timiti Festival, 20. ↩

-

Hiltebeitel, Cult of Draupadi, Volume 1: Mythologies, 15. ↩

-

Alf Hiltebeitel, The Cult of Draupadi, Volume 2: On Hindu Ritual and the Goddess (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1988), 287. ↩

-

Sambasivam Pakirisamy, interview by Tharmalingam Kavindran and author, 5 June 2022. ↩

-

Balakrishnan, interview. ↩

-

This group of volunteers is called the SLP group. S.L.P or S.L. Perumal was the son-in-law of B. Govindasamy Chettiar, the owner of the Indian Labour Company, which supplied labour to the Singapore Harbour Board. A representative of the S.L. Perumal family officiates this ritual. ↩

-

Balakrishnan, interview. ↩

-

Hiltebeitel, The Cult of Draupadi Volume 1 Mythologies: From Gingee to Kurukshetra, 440–41. ↩

-

Balakrishnan, interview. ↩

-

Lawrence A. Babb, Walking on Flowers in Singapore: A Hindu Festival Cycle Issues 26–34 (Singapore: Department of Sociology, National University of Singapore, 1974), 3. ↩

-

Raffles Museum and Library, “Letter from William Farquhar to Lieutenant L.N. Hull,” L11: Letters to and from Raffles 111, no. 7 (December 1822): 63. (From National Archives of Singapore) ↩

-

Nalina Gopal, “A Sea of Change, An Ocean of Memories,” in Singapore Indian Heritage, ed. Rajesh Rai and A. Mani (Singapore: Indian Heritage Centre, 2017), 149. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 305.89141105957 SIN) ↩

-

Babb, “Walking on Flowers in Singapore: A Hindu Festival,” 334. ↩

-

Soundara Rajan, oral history interview by Kartini Lim Chiwen, 17 December 1987, transcript and MP3 audio, Reel/Disc 16 of 23, 30:09, National Archives of Singapore (accession no. 000845), 176–78. ↩

-

H.T. Haughton, “Native Names of Streets in Singapore,” Journal of the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society 42, no. 1 (215) (July 1969): 205. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website) ↩

-

“Weird Ceremony. Strange Behaviour at A Hindu Festival. Fire-walking and Its Objects,” Straits Budget, 14 June 1906, 10. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Bharti Mukherjee, “An Invisible Woman,” Saturday Night 96 (March 1981), 36–40. ↩