Golden Mile Complex: Five Decades of an Architectural Icon

The collective sale and conservation of Golden Mile Complex will eventually restore a visionary building to its former glory, but the process will also mean the loss of a unique community that has developed there.

By Justin Zhuang

Acclaimed Dutch architect Rem Koolhaas described it a masterpiece of experimental architecture. Singaporeans were drawn to it for its atmosphere and the abundance of cheap Thai food. For Thais living in Singapore, it was a home away from home.

Golden Mile Complex, also known as Little Thailand, was sold in 2021 to a consortium which will redevelop the building. As it has been gazetted as a conserved building by the Urban Redevelopment Authority, its physical structure is likely to be preserved. However, the same cannot be said for its unique character. Its tenants – a mix of inexpensive Thai eateries, seedy bars and tiny shops selling Thai perishables – were given until May 2023 to move out. Now that they have dispersed, they are unlikely to return.

As an era in the building’s history ends, it is timely to look back at its history, which goes back five decades.

Building Golden Mile Complex

Officially opened on 28 January 1972, Golden Mile Complex was an urban renewal project by the government to “redevelop and rejuvenate the slum-ridden areas in the Singapore city centre”.1 In the 1960s, the site was home to squatter settlements, small-time furniture and rattan makers, and the Kampong Glam Community Centre.2

In June 1967, then Minister for Law and National Development E.W. Barker announced that the area would be one of 14 urban redevelopment projects which would be transformed – resulting in modern skyscrapers, luxury apartments, hotels and shops – to give rise to a “new look Singapore”. These projects would involve the participation of private enterprises.3

Singapura Developments won the tender for the three-acre site that would eventually host Golden Mile Complex with a proposal for a building by the architecture firm Design Partnership (now known as DP Architects), which was then helmed by William S.W. Lim, Tay Kheng Soon and Koh Seow Chuan. The three men had convinced Singapura Developments to bid for the site in May 1969, offering the unusual proposition for a single building that would integrate shops, offices and apartments. Although the concept differed sharply from the government’s original proposal for luxury apartments on the plot, Lim, Tay and another architect, Gan Eng Oon, proved their design could work with an economic feasibility study that included precisely calculated land and sale prices.4

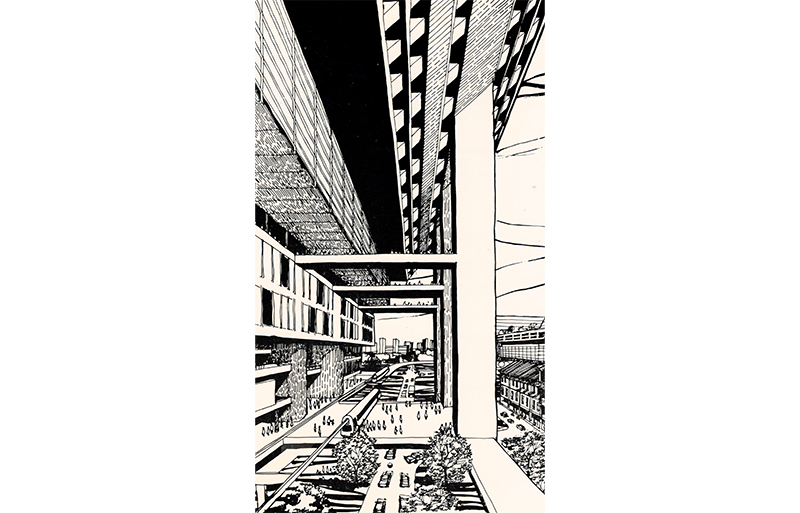

The all-in-one design of Golden Mile Complex marked a significant shift from how city planners in Singapore then traditionally segregated areas into different zones for “live, work, play”. In fact, it embodied Lim’s vision for “megastructures” that would contain all the functions of a city within a building, which he believed to be the future of Asian cities.

“We must reject outdated planning principles that seek to segregate man’s activities into arbitrary zones, no matter how attractive it may look in ordered squares on a land use map. We must reject arbitrary standards laid down that limit the intensive use of land,” said Lim and Tay as part of an essay for the Singapore Planning and Urban Research Group that was published in Asia Magazine in 1966.5 This vision was realised in Golden Mile Complex: a concrete megastructure that became one of the earliest mixed-use developments in Singapore and Asia.6

In January 1970, Singapura Developments began marketing the property and declared that “The Golden Mile Race Is On”. All 64 apartments were snapped up within a month, and most of the offices and shops were sold by the time building works commenced in May 1970.7

The building was originally named Woh Hup Complex, after the parent company of Singapura Developments. Rising 16 storeys, the edifice was designed in the Brutalist style popular in Europe and North America from the 1950s to the 1970s.8 It was constructed in a stepped terraced design held up by two end pillars that each adorned a star logo by Singapore’s leading graphic designer William Lee.9 Such a facade maximised waterfront views for the 64 apartments and maisonette penthouses spread across the topmost seven floors.

The next six floors housed 210 offices and studios to complete the tower that was seemingly pried apart in the middle. This sheltered a residential play deck facing Beach Road on the 10th storey while letting in natural light and ventilation into the office corridors and a three-storey podium. The latter comprised 360 shops that sat atop a basement carpark for 550 vehicles.

Completing the facilities was a four-storey residential car park at one end of the building that was topped with an open-air swimming pool overlooking the former Crawford Park. All these different functions were connected by corridors, including a “street” that ran through the podium of shops. The result was an interiorised environment designed to “encourage human interaction and intensify public life”.10

A Hub of Modernity

Woh Hup Complex was part of a pioneering wave of shopping centres to open in Singapore in the early 1970s, along with People’s Park Complex in Chinatown and Tanglin Shopping Centre and Specialists’ Centre in the Orchard Road area.

Like many of the complexes built then, Woh Hup Complex was also a strata-titled development. This form of property ownership was introduced by the government in 1968 to allow individual owners to have a share of a land. It allowed property developers to quickly recoup their investment by tapping on a pool of buyers, and also enabled individuals to participate in the on-going modernisation of Singapore.11

Woh Hup Complex offered shop lots in various sizes, starting from a 144-square-foot lot for just $16,500.12 The prices were lower compared to other shopping centres because the complex was at the city centre fringe. But its developer remained bullish about its prospects. “We offer easy parking, no frayed nerves while coming up here,” said T.M. Yong, a director at Singapura Developments. “Our shop owners will most probably be able to offer goods at lower prices.”13 The earliest tenants in the complex were an eclectic mix of shoe retailers, beauty salons, photo studios, furniture suppliers, travel agents, eateries, restaurants and nightclubs.14

As one of the first buildings to offer modern office spaces in Singapore, Woh Hup Complex attracted many businesses too. Singapura Developments and its parent company Woh Hup as well as Design Partnership set up offices in the building.15 The complex also became known for its many architecture and engineering firms, including OD Architects who were conceiving the masterplan for the National University of Singapore’s Kent Ridge campus, Cardew and Rider Engineers who were working with Design Partnership on Marina Square, and several engineering firms involved in the construction of Singapore’s up-and-coming Mass Rapid Transit network.16

But a decade after the complex opened, there were complaints of interrupted water supply, faulty air-conditioning and lifts, leaking roofs, rotting ceiling boards, rubbish piling up along the corridors, and broken or missing lights.17 These were reported after Woh Hup exited the property market and sold Singapura Developments along with its properties to City Developments in 1981.18 Woh Hup Complex was then renamed Golden Mile Complex.

The Rise of “Little Thailand”

By the mid-1980s, many of the building professionals had moved their offices elsewhere and Golden Mile Complex became better known as the haunt of foreign construction workers, specifically those from Thailand.

.png)

After work, particularly on Sundays and public holidays, homesick Thai workers thronged Golden Mile Complex to drink Singha beer, catch up on news back home by reading Thai newspapers, and listen to Thai music on cassette tapes. The draw for most was the various eateries selling Thai food at reasonable prices on the ground floor. Not only did these establishments serve food just like home, they served them on tables and chairs “scattered in front of food shops” or along the corridors and the concourse – just “[like] a street corner in Haadyai or Bangkok”.19

Golden Mile Complex was also the terminal for tour buses plying the Singapore-Haadyai route operated by travel agencies located in the complex and the neighbouring Golden Mile Tower. As the Thai clientele in the complex grew, it became referred to as “Little Bangkok” and “Little Thailand”.20 The Thai community injected new life into what was then a rapidly ageing Golden Mile Complex, and attracted even more shops to serve the community. A tailor in the complex reportedly expanded from one shop to seven to sell all things Thai, while a “100% genuine Thai style” disco named Pattaya opened in 1988 on the second floor.21 There was even a 50-seat “cinema” that screened kick-boxing specials and Thai features at $3 a ticket.22

In 1986, the Straits Times reported that Golden Mile Complex “would be a ghost town but for the office workers, who appear at lunch time, and the Thais, who have made it their haunt”. Dorothy, a secretary working in an architecture firm in the complex, told the Straits Times: “Before the Thais started coming here about four years ago, the place was very dead. Now, it’s sometimes so noisy that you get a headache.” Because fights would occasionally break out, she was not a fan of the place. “For Thai food, I’d rather go to Joo Chiat,” she added.23 Her sentiments were shared by many other Singaporeans who avoided Golden Mile Complex on Sundays.

As one shopowner explained: “Our Sunday business has been hit. Some customers stay away because of the Thai character of the place.” A food stall operator added: “The Thais linger for hours, drinking beer and eating their favourite beef noodles. Sometimes, they fight among themselves over a few drinks.”24

It did not help that migrant workers and the complex were often in the news for the wrong reasons. As part of the government’s massive crackdown on illegal migrants in March 1989, 370 suspected Thai undocumented workers at Golden Mile Complex were nabbed in a single operation.25

National Icon or National Disgrace?

In 1994, Rem Koolhaas visited Singapore and marvelled at its development in his seminal essay “Singapore Songlines”. He was particularly captivated by Golden Mile Complex and People’s Park Complex, which he praised as “‘masterpieces’ of experimental architecture/urbanism”.26 On his next visit to Singapore in 2005, Koolhaas said: “These buildings were not intended to be landmarks but became landmarks. Yesterday, I went to see all the buildings again, and they are absolutely stunning, radical and amazing.”27

While Koolhaas and many in the architecture fraternity saw Golden Mile Complex as the future, most Singaporeans regarded it as a relic of the past. By the 1990s, a slew of new shopping centres had sprung up near the complex, including Raffles City, Bugis Junction, Suntec City, Millenia Walk and Marina Square. Many felt Golden Mile Complex and other strata-title malls were simply no match for these single-owner developments that could plan a more attractive retail mix to woo shoppers.28 A 1996 article in the Straits Times assessed that Golden Mile Complex was unlikely to change because of its ownership structure and should simply “fill [the] low-end gap”.29

The disconnect between Golden Mile Complex’s celebrated architecture and its decline came to a head in 2006. During a parliamentary session on 6 March, then Nominated Member of Parliament Ivan Png called it a “vertical slum”. He was particularly irked by how each individual owner had added “extensions, zinc sheets, patched floors, glass, all without any regard for other owners and without any regard for national welfare”, resulting in “a terrible eyesore and a national disgrace”.

“The appearance of Golden Mile Complex appals me whenever I drive along Nicoll Highway. It must create a terrible impression on foreign visitors arriving from the airport. How can we be a world-class city in a garden? The Golden Mile Complex is just the most extreme of how a strata-title property can deteriorate,” he said.30

This came just after Golden Mile Complex was featured in Singapore 1:1 – City, a publication showcasing significant architecture and urban design in the city-state.31 “That’s a real joke!” said Png. “Can you imagine if that thing was standing on the Singapore River between OCBC Building and UOB Centre?” He added: “It just gives me goosebumps. It’s so close to the city, yet it’s so unlike Singapore – orderly, tidy, everything neat. It’ll drag us down.”32

Not everyone agreed with his criticism. Retiree Evelyn Ong, who moved into the complex in 2005, immediately booked her 11-storey apartment after seeing the breathtaking views. She said: “Once I stepped in and saw the view, I said book, book, must book.” She bought her 1,000-square-foot apartment for about $310,000, and spent about $70,000 on renovations to make it look like a holiday resort. “I think I’m very lucky. It’s so difficult to find such a nice view. Every day, I sit here (at my balcony) and I can see the beautiful lights at night.” She agreed that more could be done to spruce up the building though.33

The local architecture fraternity pushed back against Png’s comments. In August 2006, Calvin Low, a trained architect and journalist, kickstarted a monthly series on local architecture in the Straits Times and titled his first article “Golden Mile Still Shines”.

“The architectural thesis that GMC [Golden Mile Complex] represented was revolutionary – not just for Singapore but globally, too. It stood as a concrete realisation of the architects’ vision of a futuristic city-within-a-building that offered a whole, new integrated way of living in a modern, tropical, urban Asian context,” he wrote.34

In November the same year, a collective of architects, designers and artists known as FARM launched “Save the Modern Building Series”, a lineup of talks to raise awareness of the complex and other pioneering modern buildings such as Pearl Bank Apartments.35 In November 2007, the inaugural architecture festival, Singapore ArchiFest 07 – organised by the Singapore Institute of Architects to celebrate Singapore’s built environment – featured tours of the complex conducted by architecture students from the National University of Singapore.36

A Landmark Saved, a Community Lost

In August 2018, news broke that more than 80 percent of the owners of units in the complex had agreed to put the building up for an en bloc sale at $800 million. This came hot on the heels of the sale of another modernist icon, Pearl Bank Apartments,37 just six months earlier. Heritage and architectural experts were dismayed at the news. “It will be a tragedy and a great loss to Singapore if the en-bloc sale results in the demolition and redevelopment of such an important urban landmark with such high architectural and social significance,” said heritage conservation expert Ho Weng Hin.38

Although architects and academics petitioned for Golden Mile Complex to be conserved, residents were in two minds about it. The complex’s long-time residents confessed they could no longer keep up with the building’s maintenance needs. “The problem is that it’s an old building, and when it rains, the water seeps through some of the walls. The building has water-proofing issues,” said Ponno Kalastree, who had lived and worked there since 1989. He was among those who had voted for the sale and was planning to downgrade to a Housing and Development Board flat, but admitted that he would miss the place.39

To the surprise of many, the Urban Redevelopment Authority (URA) told the Business Times in October 2018 that they have “assessed the building to have heritage value, and is in the process of engaging the stakeholders to explore options to facilitate conservation”. “Modern architecture, dating from our recent past, is a significant aspect of our built heritage, and we have selectively conserved a number of such buildings. Where there is strong support and merits for conservation, we will work with the relevant stakeholders to facilitate the process,” said the URA. This meant that the existing building could be retained while a new block would be added next to it.40

The tender closed in January the following year without any offer, and a second tender launched just two months later with the same terms and price tag of $800 million suffered the same fate.41

Almost one year after the two failed collective sales, the URA announced in October 2020 that it was officially proposing Golden Mile Complex to be conserved in light of its historical and architectural significance.42 When it was gazetted a year later in October 2021, Golden Mile Complex became the “first modern, large-scale strata-titled development to be conserved in Singapore”.43

The owners relaunched an en bloc sale in December that year at the same price of $800 million.44 This time, the sale was successful and the complex was sold in May 2022 to a consortium comprising Far East Organization, Sino Land and Perennial Holdings. Although their bid was $100 million lower than the reserve price, the owners agreed to the sale within “a record time of 15 days”.45

At the point of publishing this essay, the new owners have yet to reveal how they plan to redevelop Golden Mile Complex, though it is unlikely that any of the former tenants will return. The battle to conserve Golden Mile Complex has, ironically, cost the community who kept it alive when others moved on to swankier new buildings. But all, however, is not lost. The redevelopment of Golden Mile Complex could serve as a model for how other similar buildings in Singapore can be conserved and enjoy a new lease of life for the future.

For more photos of Golden Mile Complex, click here. For a timeline, click here.

Justin Zhuang is an observer of the designed world and its impact on everyday life. He is the author of several books on architecture and design in Singapore. His latest book (co-authored with Jiat-Hwee Chang) is Everyday Modernism: Architecture & Society in Singapore (2023), the first comprehensive documentation of Singapore’s modern built environment through the lens of social cultural and architectural histories.

Justin Zhuang is an observer of the designed world and its impact on everyday life. He is the author of several books on architecture and design in Singapore. His latest book (co-authored with Jiat-Hwee Chang) is Everyday Modernism: Architecture & Society in Singapore (2023), the first comprehensive documentation of Singapore’s modern built environment through the lens of social cultural and architectural histories.NOTES

-

Singapore. Housing and Development Board, Annual Report 1965 (Singapore: Housing and Development Board, 1966), 12. (From PublicationSG); Yap Cheng Tong, “Opens Today: First of the Golden Mile Projects,” Straits Times, 28 January 1972, 20. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Chia Poteik, “$90m Plan for a New Look Singapore,” Straits Times, 16 June 1967, 5; “Fire!—By Order,” Straits Times, 1 August 1967, 20; “‘Golden Mile’ to Oust a Community Centre,” Straits Times, 26 June 1967, 7. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Chia, “$90m Plan for a New Look Singapore.” ↩

-

H. Koon Wee, “An Incomplete Megastructure: The Golden Mile Complex, Global Planning Education, and the Pedestrianised City,” The Journal of Architecture 25, no. 4 (May 2020): 472–506, ResearchGate, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/342952630_An_incomplete_megastructure_the_Golden_Mile_Complex_global_planning_education_and_the_pedestrianised_city. ↩

-

“The Future of Asian Cities,” in Singapore Planning and Urban Research Group 1965–1967 (Singapore: Singapore Planning and Urban Research Group, 1968), 8. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 307.1216095957 SIN) ↩

-

Rem Koolhaas, “Singapore Songlines: Portrait of a Potemkin Metropolis… or Thirty Years of Tabula Rasa,” in S,M,L,XL, ed. Jennifer Sigler (The Monacelli Press, 1995), 1011–87. (The National Library, Singapore, has the second edition published in 1998, call no. RART 720.92 SMA.) ↩

-

“Page 6 Advertisements Column 1,” Straits Times, 29 January 1970, 6; “Page 6 Advertisements Column 1,” Straits Times, 26 February 1970, 6. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Brutalist buildings are characterised by minimalist constructions that expose the bare building materials – such as concrete, brick, glass and steel – and other structural elements in favour of design. These buildings are usually huge and block-like concrete structures. Other examples of Brutalist buildings in Singapore include People’s Park Complex, OCBC Centre and 111 Somerset. ↩

-

“A Winner Puts His Stamp on Creative Design,” Singapore Herald, 8 October 1970, 5. (From Newslink via NLB’s eResources website) ↩

-

Calvin Chua, “Strata Megastructure: Architecture of Flexibility and Enterprise,” in The Impossibility of Mapping (Urban Asia), ed. Ute Meta Bauer, Khim Ong and Roger Nelson (Singapore: NTU Centre for Contemporary Art Singapore and World Scientific Publishing, 2020), 164–77. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 720.9590904 IMP) ↩

-

Chua, “Strata Megastructure,” 170. ↩

-

“Page 9 Advertisements Column 1,” Straits Times, 26 April 1970, 9. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Rows of Shops Make Way for Luxurious Complexes,” Straits Times, 5 September 1971, 18. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Page 23 Advertisements Column 6,” Straits Times, 9 January 1972, 23; “Page 27 Advertisements Column 1,” Straits Times, 16 May 1972, 27; “Page 9 Advertisements Column 2,” New Nation, 15 January 1972, 9; “Photography – the Easy Way Out,” New Nation, 29 August 1972, 10; “Keep the Kids Happy and Out of Your Way,” New Nation, 18 April 1972, 9; “Page 14 Advertisements Column 4,” New Nation, 11 May 1972, 14; “Page 15 Advertisements Column 1,” New Nation, 22 June 1972, 15; “Golden Rajah Lounge for Fine Cuisine, Service,” Straits Times, 7 May 1973, 33, “Big Three Opens for Business,” Straits Times, 8 January 1972, 11. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Robert Powell, “Inciting Rebellion,” in No Limits: Articulating William Lim (Singapore: Select Publishing, 2002), 14–46. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 720.92 NO) ↩

-

Peter Keys, “Where Architects Go for Lunch,” Straits Times, 21 April 1984, 5. (From Newslink via NLB’s eResources website) ↩

-

Ang Peng Hwa, “Angry Petition by Golden Mile Complex Residents,” Singapore Monitor, 31 July 1983, 45; “Zoulang laji yue ji yue duo” 走廊垃圾越积越多 [Corridor litter piles up], 新明日报 Shin Min Daily, 1 December 1983, 23; “Mei feng xia dayu wuding bi loushui” 每逢下大雨屋顶必漏水 [Whenever it rains heavily, the roof will leak], 联合早报 Lianhe Zaobao, 11 May 1983, 5; “Tenants Fume Over the Heat,” Straits Times, 16 August 1984, 14. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Choo Ai Leng, “City Developments Sits on Solid Base,” Business Times, 7 May 1981, 11. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

May Ho, “Where Thais Meet and Watch the World Go By,” Straits Times, 21 August 1986, 2. (From Newslink via NLB’s eResources website); May Ho, “Like a Street Corner in Haadyai,” Straits Times, 21 August 1986, 2. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Lito Gutierrez and Wong Kwai Chow, “Little Bangkok at the Golden Mile,” Straits Times, 6 January 1985, 3. (From NewspaperSG); Ho, “Where Thais Meet and Watch the World Go By.” ↩

-

Annie Low, “Business at Its Sunday Best,” Straits Times, 25 April 1988, 11. (From Newslink via NLB’s eResources website); “Ba di ya wuting yezonghui kaimu zhi qing youdai jia bin” 芭堤雅舞厅夜总会开幕志庆优待嘉宾 [Pattaya ballroom nightclub opening celebration with special guests], 联合晚报 Lianhe Zaobao, 2 March 1988, 9; “Page 6 Advertisements Column 1,” Timeszone Central, 15 February 1990, 6. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Luo Guowei 罗国威, “Hehe dasha nei xiao xiyuan zhuan fang taiyu pian” 和合大厦内小戏院专放泰语片 [The small theatre in Woh Hup Complex exclusively screens Thai-language films], 联合晚报 Lianhe Zaobao, 26 August 1990, 7; “B-Grade Heaven at Beach Road,” Straits Times, 16 September 1990, 15. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

K.F. Tang, “What Price Foreign Workers?,” Straits Times, Sunday Plus, 21 February 1988, 1. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Sharon Lim, “370 Suspected Thai Illegal Immigrants Held at Beach Road,” Straits Times, 13 March 1989, 1. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Koolhaas, “Singapore Songlines,” 1061. ↩

-

Parvathi Nayar, “Script Writer of a Different Kind,” Business Times, 17 December 2005, 5. (From Newslink via NLB’s eResources website) ↩

-

Danny Yeo, “Old Shopping Centres Need More Than a Facelift to Survive,” Business Times, 31 August 1993, 54. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Evelyn Yap, “Not Quite the Golden Mile, But There’s Hope,” Sunday Times, 14 April 1996, 3. (From Newslink via NLB’s eResources website) ↩

-

Singapore Parliament, “Parliamentary Debates Singapore Official Report Tenth Parliament Part II of Second Session,” 6 March 2006, Budget, https://sprs.parl.gov.sg/search/#/topic?reportid=006_20060306_S0004_T0005. ↩

-

Wong Yunn Chii, et al., Singapore 1:1 City: A Gallery of Architecture & Urban Design (Singapore: Urban Redevelopment Authority, 2005), 162. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RART 720.95957 WON) ↩

-

Clarence Chang, “It’s So Unlike Orderly S’pore,” New Paper, 7 March 2006, 4. (From Newslink via NLB’s eResources website) ↩

-

Desmond Ng and Esther Huang, “National Disgrace? But the View Is Great,” New Paper, 7 March 2006, 4. (From Newslink via NLB’s eResources website) ↩

-

Calvin Low, “Golden Mile Still Shines,” Straits Times, 5 August 2006, 13. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

David Chew, “Fighting for Our Landmarks,” Today, 11 November 2006, 58. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Tay Suan Chiang, “Tours Down Memory Lane,” Straits Times, 1 November 2007, 16. (From Newslink via NLB’s eResources website) ↩

-

Justin Zhuang, “Saving Pearl Bank Apartments,” BiblioAsia 12, no. 3 (October–December 2016): 12–16. ↩

-

Melody Zaccheus, “Golden Mile Complex Gets More Than 80 Per Cent Votes from Owners to Launch En Bloc Sale,” Straits Times, 11 August 2018, https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/golden-mile-complex-gets-more-than-80-per-cent-votes-from-owners-to-launch-en-bloc-sale. ↩

-

Desmond Ng and Lam Shushan, “From the Occult to a Derelict Pool: 12 Things About Golden Mile Complex You Didn’t Know,” CNA, 30 September 2018, https://www.channelnewsasia.com/cnainsider/golden-mile-complex-occult-pool-conservation-brutalist-800971; Melody Zaccheus, “Farewell Golden Mile Complex? Residents Open Up About Their Love-Hate Relationship with the Landmark,” Straits Times, 22 September 2018, https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/farewell-golden-mile-complex-residents-open-up-about-their-love-hate-relationship-with-the. ↩

-

Yunita Ong, “Golden Mile Complex May Stay – Even with En Bloc,” Business Times, 31 October 2018, https://www.businesstimes.com.sg/property/golden-mile-complex-may-stay-even-en-bloc. ↩

-

Wong Pei Ting, “Conservation Clause in Golden Mile Complex En Bloc a Tough Sell: Analysts,” Today, 27 March 2019, https://www.todayonline.com/singapore/conservation-clause-golden-mile-complex-en-bloc-tough-sell-analysts; Grace Leong, “Conserved Landmark Golden Mile Complex Up for En Bloc Sale Again at $800m,” Business Times, 1 December 2021, https://www.straitstimes.com/business/property/conserved-landmark-golden-mile-complex-up-for-en-bloc-sale-again-at-800m. ↩

-

“Supporting the Conservation and Commercial Viability of Golden Mile Complex,” Urban Redevelopment Authority, 9 October 2020, https://www.ura.gov.sg/Corporate/Media-Room/Media-Releases/pr20-28. ↩

-

Davina Tham, “Golden Mile Complex Gazetted as Conserved Building,” CNA, 22 October 2021, https://www.channelnewsasia.com/singapore/golden-mile-complex-conserved-building-gazetted-2261896. ↩

-

Leong, “Conserved Landmark Golden Mile Complex Up for En Bloc Sale Again at $800m.” ↩

-

Isabelle Liew, “Golden Mile Complex Sold for $700m, Developers to Restore Building,” Straits Times, 6 May 2022, https://www.straitstimes.com/business/property/golden-mile-complex-sold-for-700m-developers-to-restore-building. ↩